A Patient’s Guide to Wrist Fusion

Introduction

Arthritis of the wrist has many causes, and there are many ways of treating the pain. These treatments can be very successful, at least for awhile. But eventually the entire wrist can become so painful that nonsurgical treatments don’t work anymore. At this point, your surgeon may recommend a wrist fusion. Wrist fusion may also be necessary after severe trauma to the wrist. Fusion is sometimes called arthrodesis.

This guide will help you understand

- how a wrist fusion eases the pain of arthritis

- how surgeons perform the operation

- what the recovery process is like

Anatomy

What parts of the wrist are involved?

The anatomy of the wrist joint is extremely complex, probably the most complex of all the joints in the body. The wrist is actually a collection of many joints and many bones. These joints and bones let us use our hands in many ways. The wrist must be extremely mobile to give our hands a full range of motion. At the same time, the wrist must provide the strength for heavy gripping.

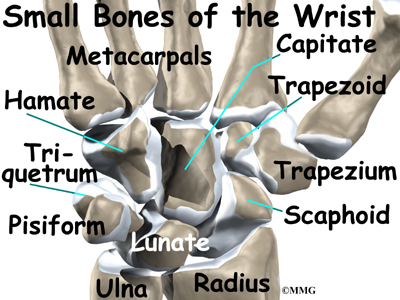

The wrist is made up of eight separate small bones, called the carpal bones. The carpal bones connect the two bones of the forearm, the radius and the ulna, to the bones of the hand. The metacarpal bones are the long bones that lie mostly within the palm. The metacarpals are in turn attached to the phalanges, the bones in the fingers and thumb.

One reason that the wrist is so complex is that every small bone forms a joint with the bone next to it. This means that what we call the wrist joint is actually many small joints. Ligaments connect all the small bones to each other, and to the radius, ulna, and metacarpal bones.

Articular cartilage is the smooth, rubbery material that covers the bone surfaces in most joints. It protects the bone ends from friction when they rub together as the joint moves. Articular cartilage also acts sort of like a shock absorber. Damage to the articular cartilage eventually leads to degenerative arthritis.

When the articular cartilage is worn away over time, the bones begin to rub against each other. This causes the pain of degenerative arthritis. Degenerative arthritis is also called osteoarthritis.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Osteoarthritis of the Wrist Joint

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Wrist Anatomy

Rationale

Why do I need wrist fusion surgery?

Many of the small joints in the wrist can become arthritic. When this happens, the wrist joint can become extremely painful. Moving your wrist may become difficult because of the pain and stiffness. Your grip can also get weak from the pain. Whenever the hand grips or uses strength in any way, the wrist feels the force. This happens because the muscles running from the forearm to the hand contract, tightening the wrist bones together. This causes pain.

In advanced problems with arthritis, the alignment of the wrist can change, leading to deformity. Fusing the bones together is a way to improve the alignment and prevent further deformation. Fusion may also be needed to align the wrist after a severe wrist injury.

A fusion of any joint eliminates pain by making all the bones grow together into one solid bone. When the bone ends can no longer rub together, there is no more pain. Fusion surgeries are used in many joints. Fusion surgeries were very common before the invention of artificial joints.

A wrist fusion is somewhat different from fusion in other joints. Most joints are made up of only two bones. Wrist fusion involves getting 12 or 13 bones to grow together.

The goal of a wrist fusion is to get the radius in the forearm, the carpal bones of the wrist, and the metacarpals of the hand to fuse into one long bone. The ulna of the forearm is not included in the fusion. The joints between the ulna and the radius are what allow you to turn the palm of your hand up and down. By not fusing the ulna, you should still be able to rotate your hand. However, you will not be able to bend your wrist after the operation.

A wrist fusion is a trade-off. You will lose some motion, but you will regain a strong and pain-free wrist. Regaining strength is especially important to younger people who need to work with their hands. These patients need strength more than flexibility. Wrist fusion gives them a strong wrist that is good for gripping. Patients who need more movement than strength should consider another type of operation, such as an artificial wrist joint replacement.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Wrist

Preparations

What do I need to do before surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery must be made jointly by you and your surgeon. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before. The amount of time patients spend in the hospital varies.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during wrist fusion surgery?

Surgeons fuse wrists in many different ways. In the past, most of the procedures used a bone graft from your pelvis. Surgeons now try to take a small amount of bone from the end of the radius bone instead. A bone graft involves taking bone tissue from one area and transplanting it into another area. This encourages the ends of the bone to grow together. If your surgeon grafts bone from your pelvis, you will have two incisions, one on the back of your wrist, and another on the side of your hip. Your surgeon may also try to fuse the bones without a graft.

Surgery can last up to 90 minutes. Surgery may be done using a general anesthetic, which puts you to sleep during surgery. In some cases, surgery is done using a local anesthetic, which numbs just the wrist and hand. With a local anesthetic you may be awake during the surgery, but your surgeon will make sure you don’t see the operation.

Once you have anesthesia, your surgeon will make sure the skin of your wrist and hand are free of infection by cleaning the skin with a germ-killing solution. The surgeon then makes an incision down the back of the wrist. Since most of the blood vessels and nerves are on the other side of the wrist, going through the back helps prevent nerve and vessel damage.

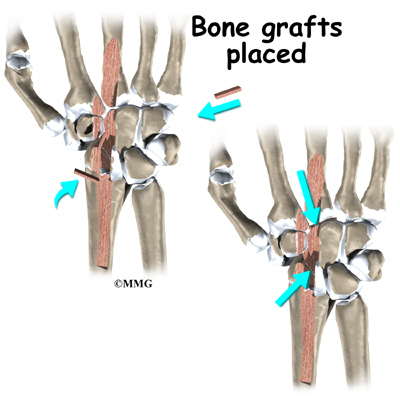

Next, the tendons and ligaments are moved to the side. This allows the surgeon to see all the bones and joints of the wrist. The articular cartilage is then removed from each joint that will be fused. At this point, the wrist joint consists of many small bones with space between them where the cartilage is missing. If you are getting a bone graft, the graft is placed between each of the spaces in the wrist bones.

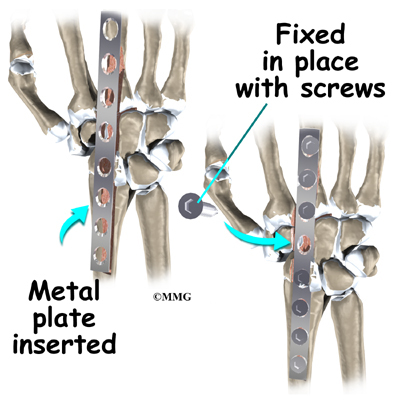

The surgeon places a metal plate with screw holes on the back of the wrist. The plate goes from the radius to the metacarpal bone of the middle finger. The plate is attached to the bone with metal screws. The plate keeps the bones from moving so that they stay in proper alignment while they grow together. The plate usually stays inside your hand permanently. It is not removed unless it causes problems.

At the end of the operation, the incisions are stitched together. Your arm is placed in a large, rigid splint or cast, and you are woken up and taken to the recovery room.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following wrist fusion are

- infection

- nerve and blood vessel injury

- tendon irritation

- nonunion of the bones

Infection

Any surgery carries the risk of infection. You will probably be given antibiotics before the procedure to reduce the risk. If you get an infection, you will need more antibiotics. If the areas around the bone graft and metal plate become infected, you may need surgery to drain the infection.

Nerve and Blood Vessel Injury

All of the nerves and blood vessels that go to the hand travel across the wrist joint. Because the operation is performed so close to them, it is possible to injure either the nerves or the blood vessels during surgery. Retractors that hold the nerves and vessels out of the way during surgery may cause temporary damage. Permanent injury to the nerves or blood vessels rarely happens, but it is possible.

Tendon Irritation

The plate that is screwed into the back of the wrist can irritate the tendons that cross this part of the wrist. If this happens, you may need short-term treatment with medication, ice, or visits to a physical or occupational therapist. If pain and irritation still don’t go away after trying these treatments, your surgeon may have to remove the plate. Surgeons will try to wait to do this until they are certain the bones have fused together.

Nonunion

Sometimes the bones do not fuse as planned. This is called a nonunion, or pseudarthrosis (false joint). If the joint motion from a nonunion continues to cause pain, you may need a second operation. In the second procedure, the surgeon usually adds more bone graft and checks that the plates and pins are holding the bones still. The bones need to be completely immobilized for fusion to occur.

After Surgery

What can I expect after surgery?

After surgery, you will wear an elbow-length cast for about six weeks. This holds the wrist still while the ends of the bones fuse together. Your surgeon will want to check your hand within five to seven days. Stitches will be removed after 10 to 14 days, although most of them will have been absorbed by your body. You may have some discomfort after surgery. Your surgeon can give you pain medicine to control the discomfort.

You should keep your hand and wrist elevated above the level of your heart for several days to avoid swelling and throbbing. Keep it propped up on a stack of pillows when sleeping or sitting up.

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

A removable splint replaces the cast after six to eight weeks. You can then take the splint off to do your exercises during the day. The joints in the fingers may feel stiff or sore from the immobility caused by the cast.

If you still have pain, or if the stiffness in the joints above or below the wrist doesn’t improve, you may need a physical or occupational therapist to direct your recovery program. The first few therapy treatments will focus on controlling the pain and swelling from surgery. Your therapist may use gentle massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain. Then you’ll begin gentle range-of-motion exercises for the joints above and below the wrist.

Your surgeon will X-ray the wrist several times after surgery to make sure that the bones are healing properly. Once your surgeon is sure that fusion has occurred, you will begin a strengthening program. It will take some time to regain the strength in your hand and arm. As with any surgery, you need to avoid doing too much, too quickly.

Strengthening exercises give you added stability around the wrist joint. Some of the exercises you’ll do are designed to get your hand and wrist working in ways that are similar to your work tasks and daily activities. Your therapist will teach you ways to use your hand and arm so that you can do your tasks safely and with the least amount of stress on your wrist. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

Your therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control, improve strength, and to regain fine motor abilities with your wrist and hand. When you are well under way, your regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource, but you’ll be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.