A Patient’s Guide to Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC) Injuries

Introduction

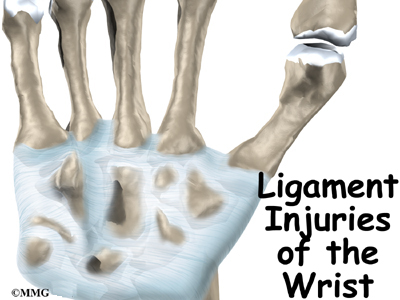

Triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) injuries of the wrist affect the ulnar (little finger) side of the wrist. Mild injuries of the TFCC may be referred to as a wrist sprain. As the name suggests, the soft tissues of the wrist are complex. They work together to stabilize the very mobile wrist joint. Disruption of this area through injury or degeneration can cause more than just a wrist sprain. A TFCC injury can be a very disabling wrist condition.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts if the wrist are involved

- how these injuries occur

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the wrist are involved?

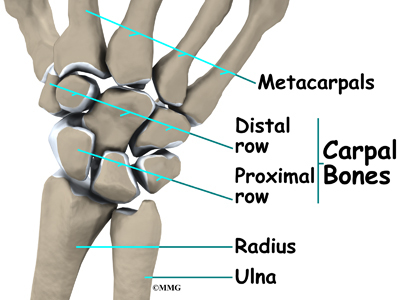

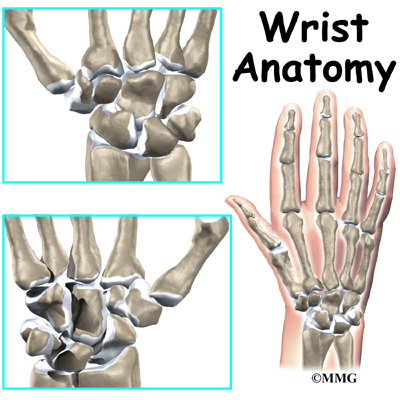

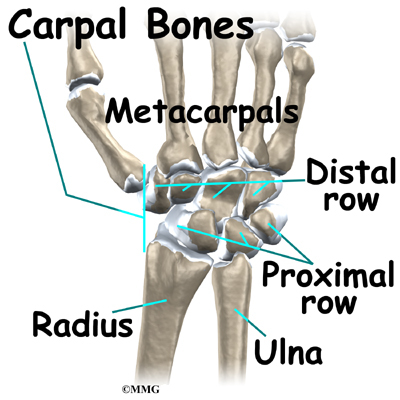

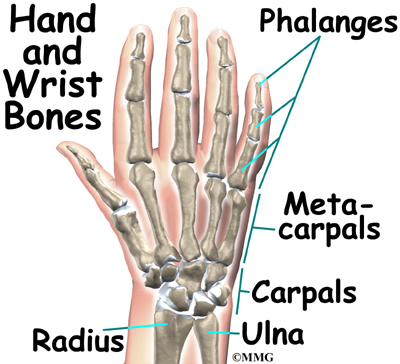

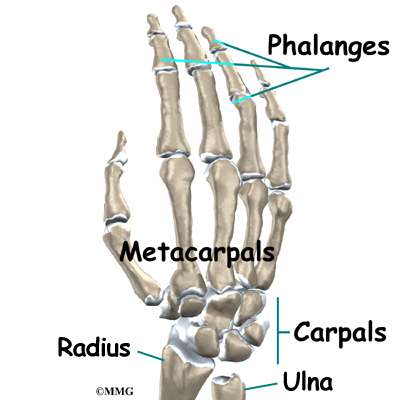

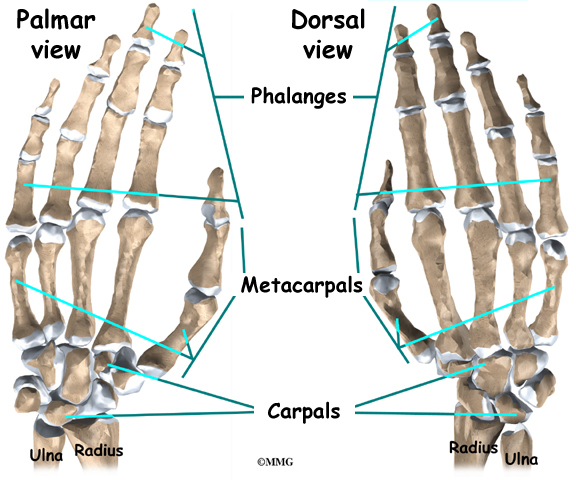

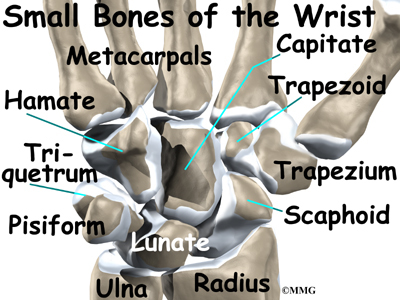

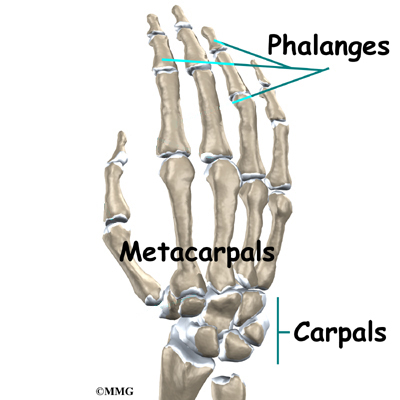

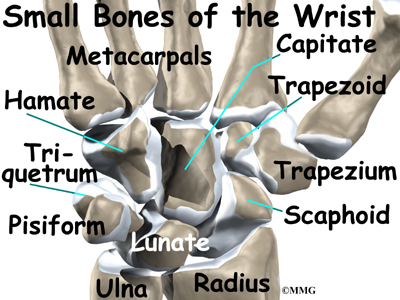

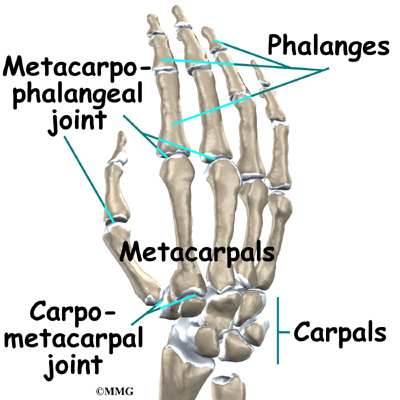

The wrist is actually a collection of many bones and joints. It is probably the most complex of all the joints in the body. There are 15 bones that form connections from the end of the forearm to the hand.

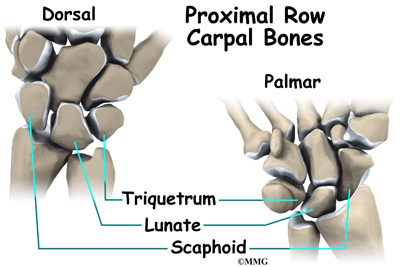

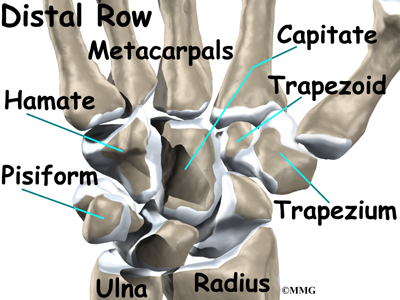

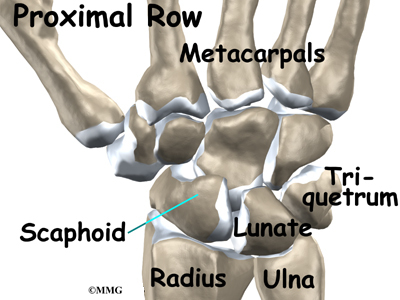

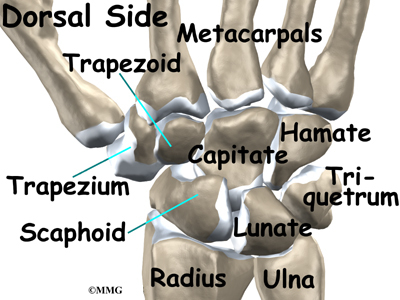

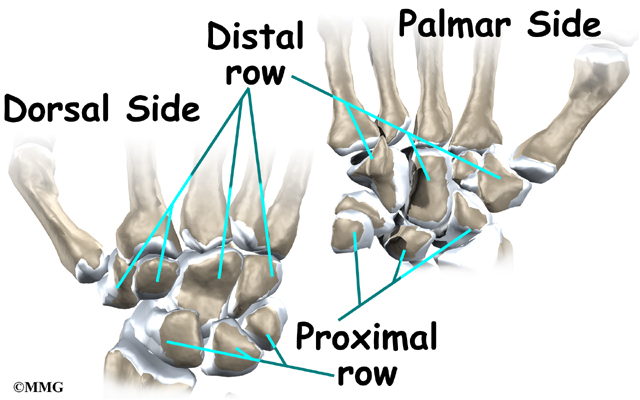

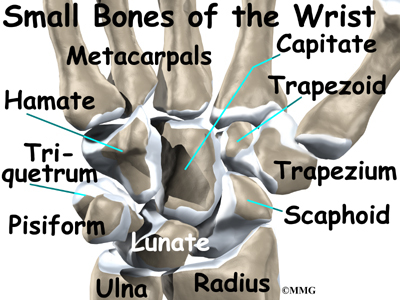

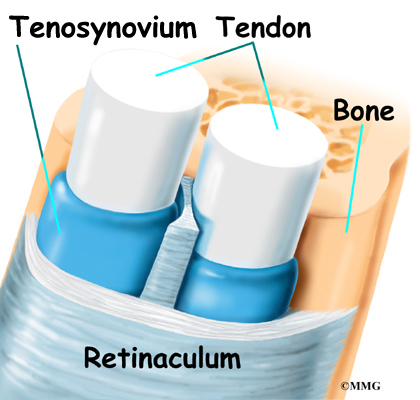

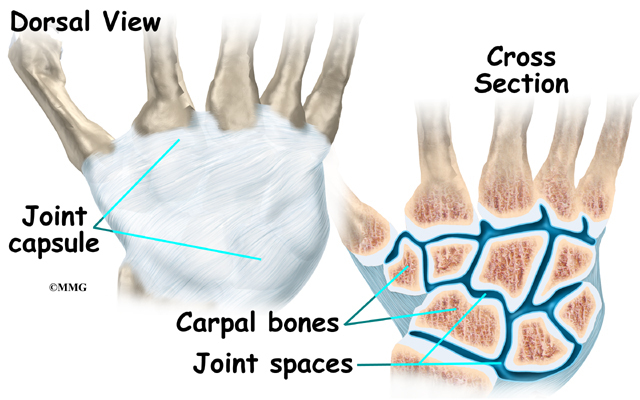

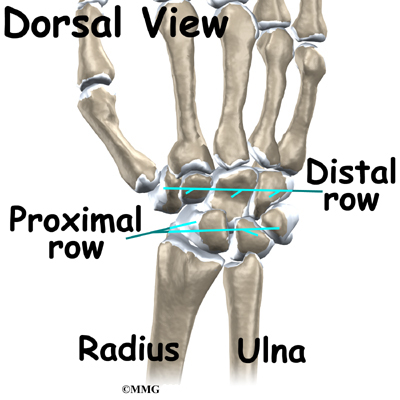

The wrist itself contains eight small bones, called carpal bones. These bones are grouped in two rows across the wrist. The proximal row is where the wrist creases when you bend it. The second row of carpal bones, called the distal row, meets the proximal row a little further toward the fingers.

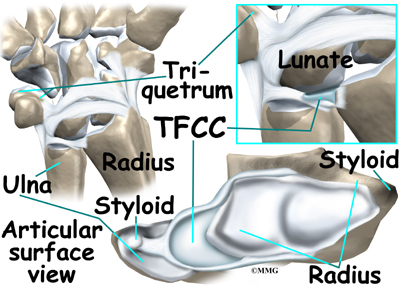

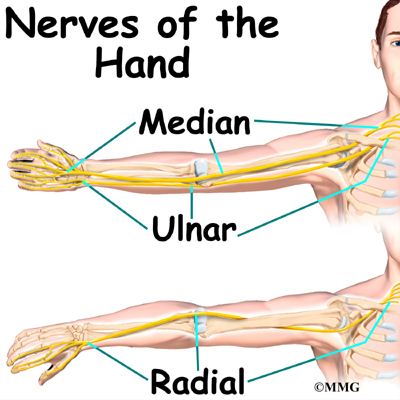

The proximal row of carpal bones connects the two bones of the forearm, the radius and the ulna, to the bones of the hand. On the ulnar side of the wrist, the end of the ulna bone of the forearm moves with two carpal bones, the lunate and the triquetrum.

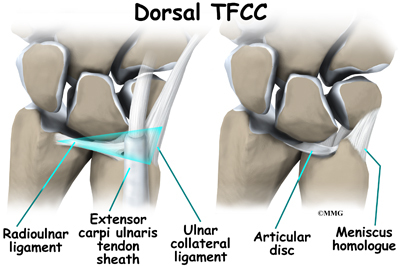

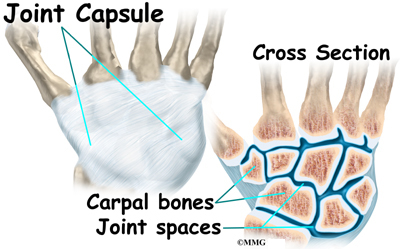

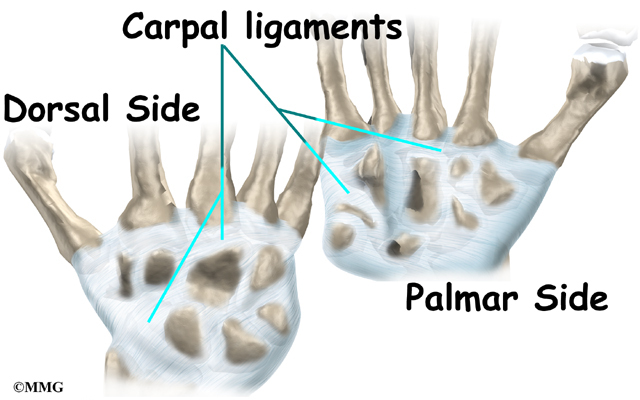

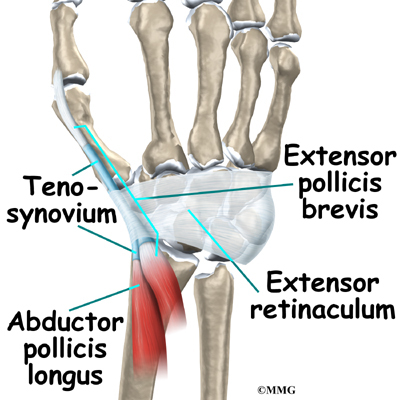

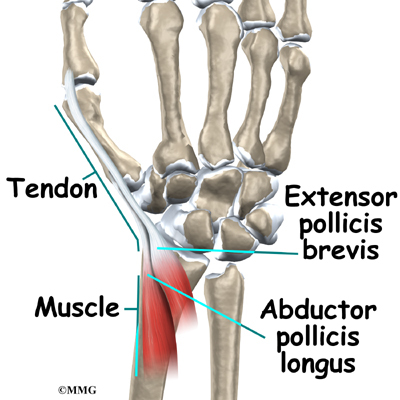

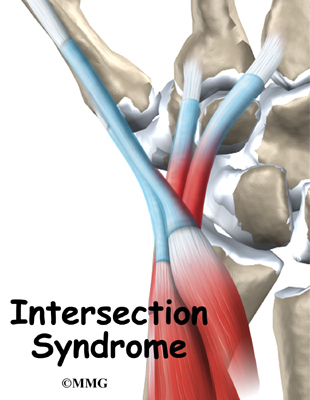

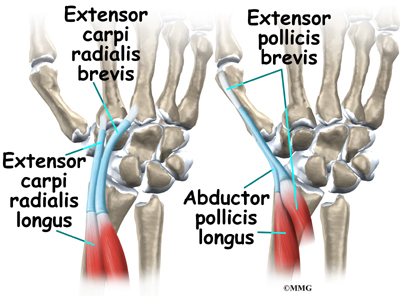

The triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) suspends the ends of the radius and ulna bones over the wrist. It is triangular in shape and made up of several ligaments and cartilage. The TFCC makes it possible for the wrist to move in six different directions (bending, straightening, twisting, side-to-side).

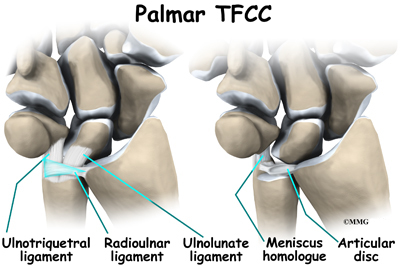

The entire triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) sits between the ulna and two carpal bones (the lunate and the triquetrum). The TFCC inserts into the lunate and triquetrum via the ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments. It stabilizes the distal radioulnar joint while improving the range of motion and gliding action within the wrist.

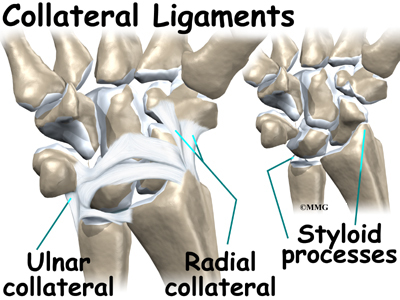

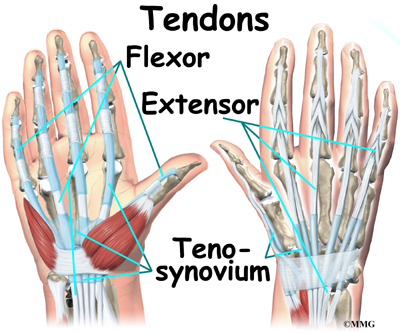

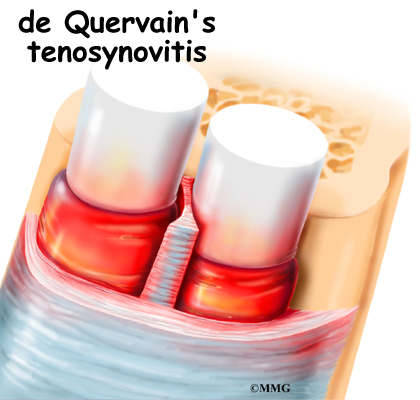

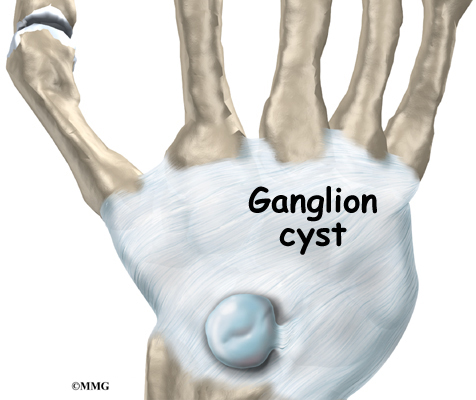

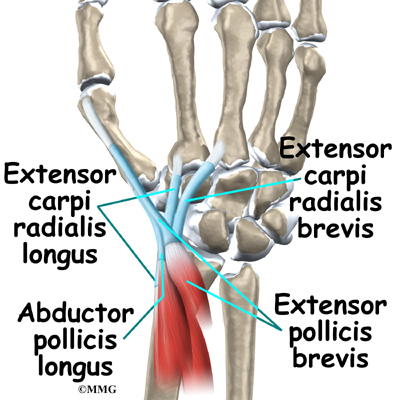

There is a small cartilage pad called the articular disc in the center of the complex that cushions this part of the wrist joint. Other parts of the complex include the dorsal radioulnar ligament, the volar radioulnar ligament, the meniscus homologue (ulnocarpal meniscus), the ulnar collateral ligament, the subsheath of the extensor carpi ulnaris, and the ulnolunate and ulnotriquetral ligaments.

Injury to the triangular fibrocartilage complex involves tears of the fibrocartilage articular disc and meniscal homologue. The homologue refers to the piece of tissue that connects the disc to the triquetrum bone in the wrist. The homologue acts like a sling or leash between these two structures.

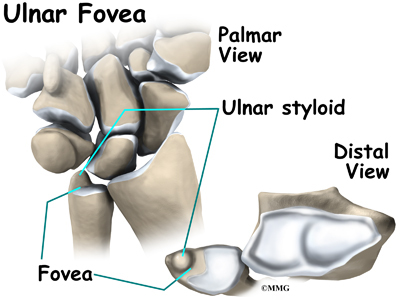

Another important structure to understand with TFCC injuries is the ulnar fovea. The fovea is a groove that separates the ulnar styloid from the ulnar head. The groove is at the junction of the ulnar bone and wrist. The styloid is a small bump on the edge of the wrist (on the side away from the thumb) where the ulna meets the wrist joint. Later we will talk about the fovea test to diagnose TFCC injuries.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Wrist Anatomy

Causes

What causes this problem?

The triangular fibrocartilage complex stabilizes the wrist at the distal radioulnar joint. It also acts as a focal point for force transmitted across the wrist to the ulnar side. Traumatic injury or a fall onto an outstretched hand is the most common mechanism of injury. The hand is usually in a pronated or palm down position. Tearing or rupture of the TFCC occurs when there is enough force through the ulnar side of the hyperextended wrist to overcome the tensile strength of this structure.

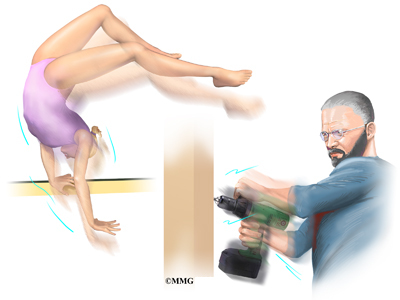

High-demand athletes such as tennis players or gymnasts (including children and teens) are at greatest risk for TFCC injuries. TFCC injuries in children and adolescents occur more often after an ulnar styloid fracture that doesn’t heal.

Power drill injuries can also cause triangular fibrocartilage complex rupture when the drill binds and the wrist rotates instead of the drill bit. Triangular fibrocartilage complex

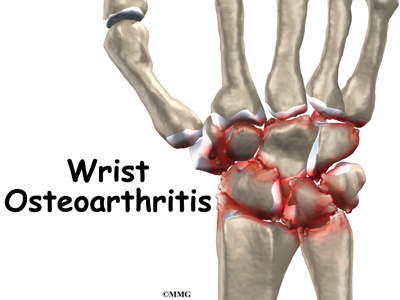

(TFCC) tears can also occur with degenerative changes. Repetitive pronation (palm down position) and gripping with load or force through the wrist are risk factors for tissue degeneration. Degenerative changes in the TFCC structure also increase in frequency and severity as we get older. Thinning soft tissue structures can result in a TFCC tear with minor force or minimal trauma.

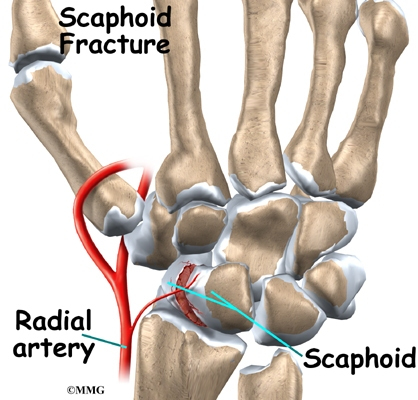

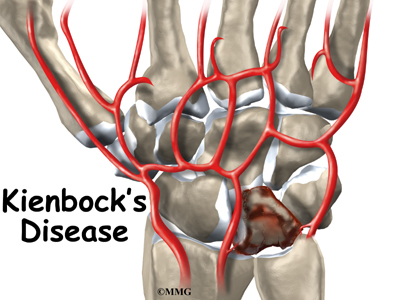

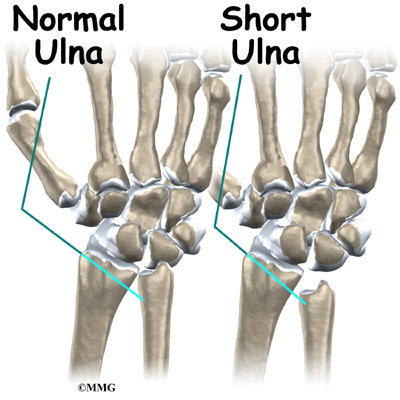

There may be some anatomical risk factors. Studies show that patients with a torn TFCC often have ulnar variance and a greater forward curve in the ulnar bone. Ulnar variance means the ulna is longer than the radius because of congenital (present at birth) shortening of the radius bone in the forearm.

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

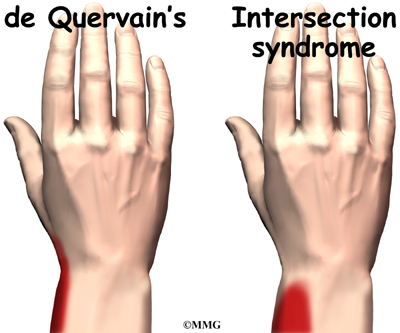

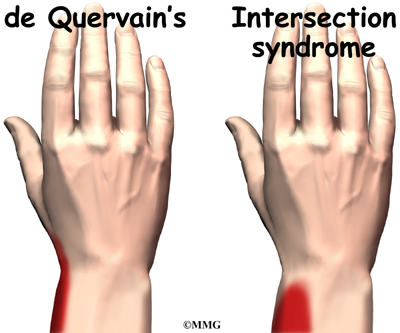

Wrist pain along the ulnar side is the main symptom. Some patients report diffuse pain. This means the pain is throughout the entire wrist area. It can’t be pinpointed to one area. The pain is made worse by any activity or position that requires forearm rotation and movement in the ulnar direction. This includes simple activities like turning a doorknob or key in the door, using a can opener, or lifting a heavy pan or gallon of milk with one hand.

Other symptoms include swelling; clicking, snapping, or crackling called crepitus; and weakness. Some patients report a feeling of instability, like the wrist is going to give out on them. You may feel as if something is catching inside the joint. There is usually tenderness along the ulnar side of the wrist.

If a fracture at the distal end of the ulna bone (at the wrist) is present along with soft tissue instability, then forearm rotation may be limited. The direction of limitation (palm up or palm down) depends on which direction the ulna dislocates.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the problem?

Your physician relies on the history (how, when, and what happened), symptoms, and physical examination to make the diagnosis. Tests of joint stability can be conducted. Special tests such as stress testing of the wrist radioulnar and ulnocarpal joints help define specific areas of injury.

An accurate diagnosis and grading of the injury (degree of severity) is important. Usually, the grade is based on how much disruption of the ligament has occurred (minimal, partial, or complete tear). There are two basic grades of triangular fibrocartilage complex injuries. Class 1 is for traumatic injuries. Class 2 is used to label or describe degenerative conditions.

Other tests may be done to provoke the symptoms and test for excess movement. These include hypersupination (overly rotating the forearm in a palm-up position) and loading the wrist in a position of ulnar deviation (moving hand away from the thumb) and wrist extension.

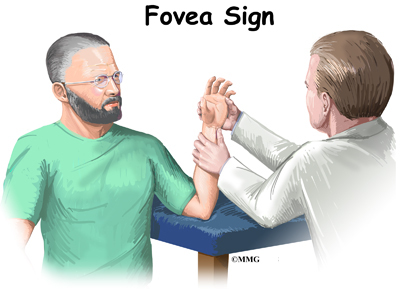

A new test called the fovea sign applies external pressure to the area of the fovea. The examiner compares the involved wrist with the wrist on the other side. Tenderness and pain during this test is a sign that there is a split-tear injury (down the middle length-wise).

Split tears are more common with lower energy, repetitive torque injuries such as from bowling or golf. This type of ligament injury was first discovered when a surgeon pushed on the area of pain while using an arthroscope to look inside the joint. The surgeon saw the ligament open up like a book.

X-rays may show disruption of the triangular fibrocartilage complex when there is a bone fracture present. Ligamentous instability without bone fracture appears normal on standard X-rays. X-rays with a dye injected is called a wrist arthrography. Arthrography is positive for a TFCC tear if the dye leaks into any of the joints. There are three specific joint areas tested, so this test is called a triple injection wrist arthrogram.

Acute injuries can be painfully swollen preventing proper examination. In such cases, more advanced imaging such as MRI (with or without a contrast dye) can be used to detect ligamentous or other soft tissue damage. When MRI is done with a dye injected into the area, the testing procedure is still called arthrography. The test itself is an MRI arthrogram. If the dye moves from one joint compartment to another, a tear of the soft tissues is suspected. But studies show that almost half the patients with a true triangular fibrocartilage complex tear have normal arthrograms.

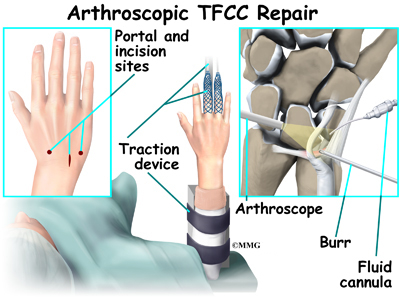

Wrist arthroscopy is really the best way to accurately assess the severity of damage. At the same time, the surgeon looks for other associated injuries of ligaments and cartilage. The surgeon performs the test by inserting a long thin needle into the joint. A tiny TV camera on the end of the instrument allows the surgeon to look directly at the ligaments.

Using a probe, the surgeon tests the integrity of the soft tissues. A special trampoline test can be done to see if the fibrocartilage disk is okay. The surgeon presses the center of the disk with the probe. Good tension and an ability to bounce back show that the disk is attached normally and is not torn or damaged. If the probe sinks as if on a feather bed, the test is positive (indicates a tear). One advantage of an arthroscopic exam is that treatment can be done at the same time.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

If the wrist is still stable, then conservative (nonoperative) care is advised. You may be given a temporary splint to wear for four to six weeks. The splint will immobilize (hold still) your wrist and allow scar tissue to help heal it. Anti-inflammatory drugs and physical therapy may be prescribed. You may benefit from one or two steroid injections spaced apart by several weeks.

If the wrist is unstable but you don’t want surgery, then the surgeon may put a cast on your wrist and forearm. It may be possible to use a splint for six weeks (instead of casting) and then start physical therapy. Your doctor will help you decide what would be best for your particular injury.

Surgery

Surgical treatment is based on the specific injury present. Instability as a result of complete ligamentous ruptures, especially with bone fracture, requires surgery as soon as possible.

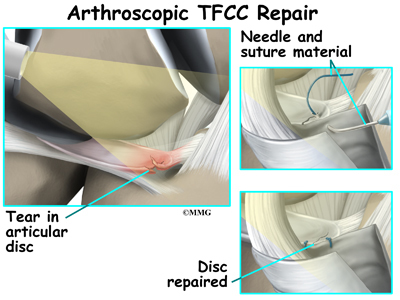

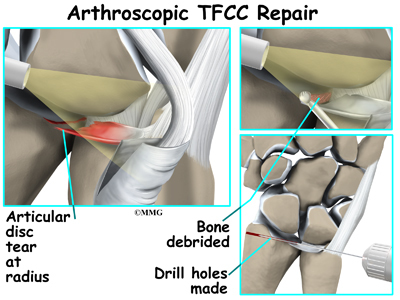

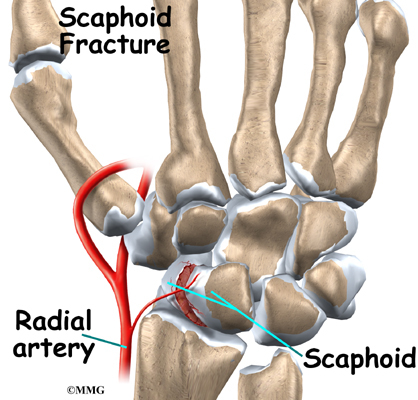

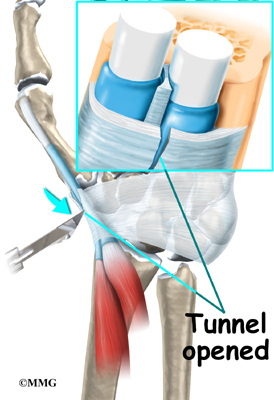

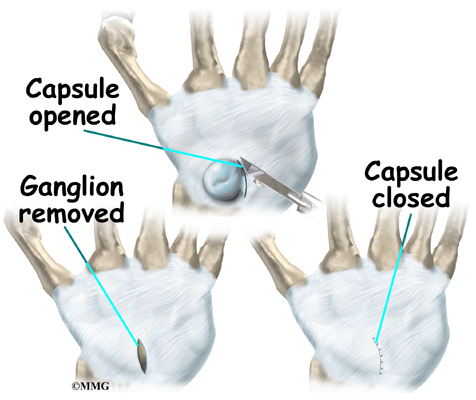

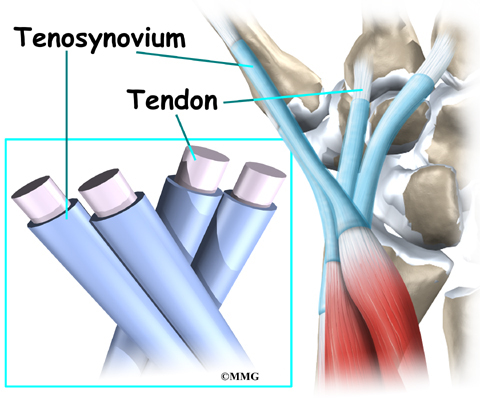

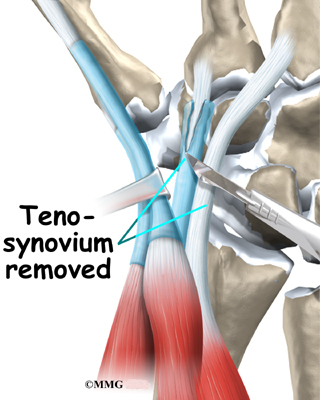

The outside perimeter of the triangular fibrocartilage complex has a good blood supply. Tears in this area can be repaired. But there is no potential for healing when tears occur in the central area where there is no blood supply. Arthroscopic debridement (smoothing or shaving) of the damaged tissue is then required.

The surgeon debrides any tears of the disc or meniscal homologue that might catch against other joint surfaces. Then the surgeon looks for any problems with the foveal ligament. A probe is used to detect tension or laxity (looseness) of the ligaments. Laxity is a sign of injury.

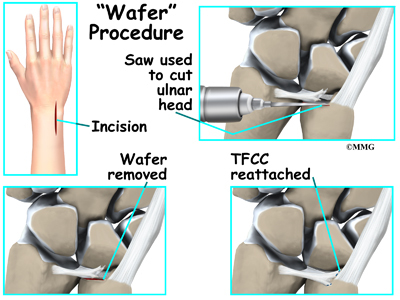

Arthroscopic debridement works well for simple tears. Much of the damaged tissue can be removed while still keeping a stable wrist joint. The torn structures can be reattached with repair sutures. Some surgeons perform an arthroscopic wafer procedure in addition to the TFCC debridement especially when both TFCC disruption and positive ulnar variance are present. Further studies are needed to see if the combined procedure results in a more satisfactory outcome than current methods and to evaluate a rotational loss that can occur with this combined procedure.

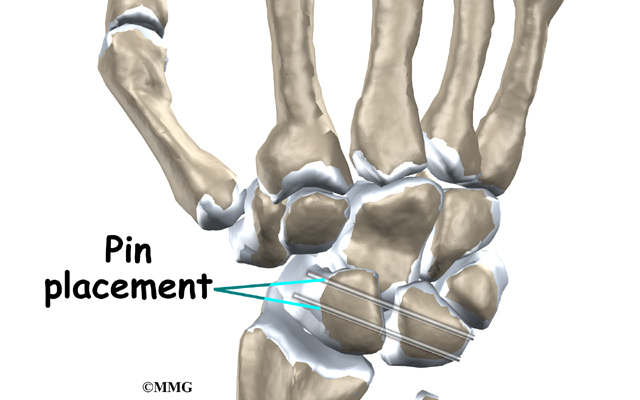

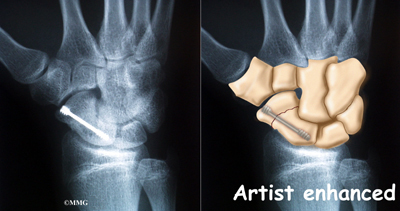

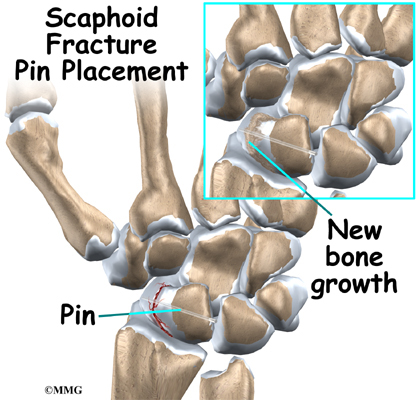

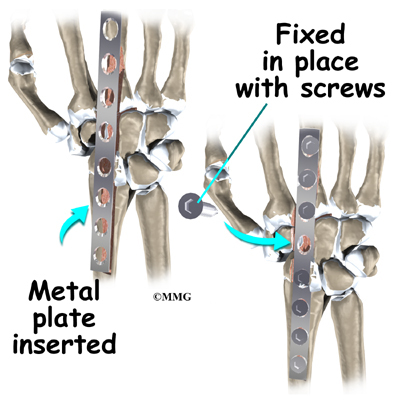

Some ligamentous ruptures with fracture can also be repaired arthroscopically with reattachment and instrumentation. Instrumentation refers to the use of hardware such as wires and screws to help hold the repaired tissue in place until healing occurs.

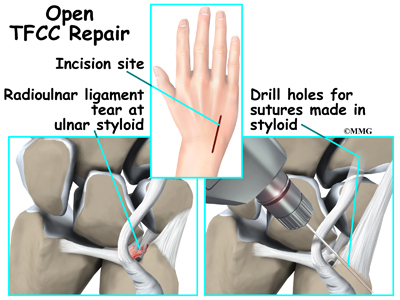

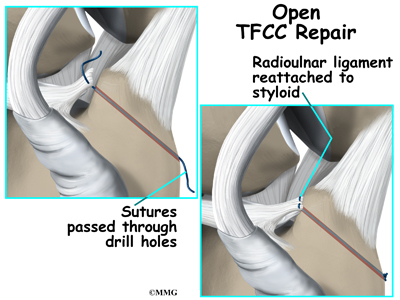

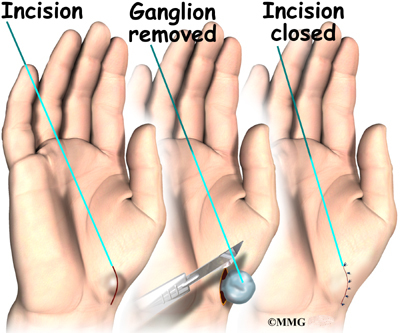

Although they are few, there are some complex tears that require open repair. Open repair means the surgeon makes an incision and opens the tissues to perform the operation. This gives the surgeon a better view and better access of the area. The specific procedure depends on the tissues injured and the extent of the injury. For example, detachment of the radioulnar ligaments usually requires open repair. Instability of the distal radioulnar joint may require the use of wires to hold the area together until healing occurs.

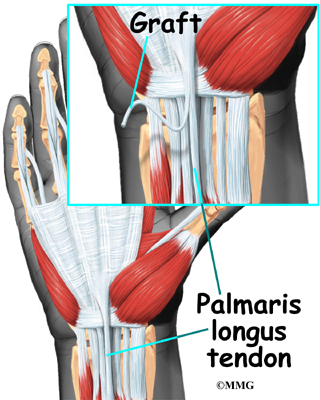

In other cases, surgery has been delayed long enough that the torn ligament has retracted (pulled back) so far that direct repair can’t be done. In these cases, a tendon graft may be needed to help strengthen the repair.

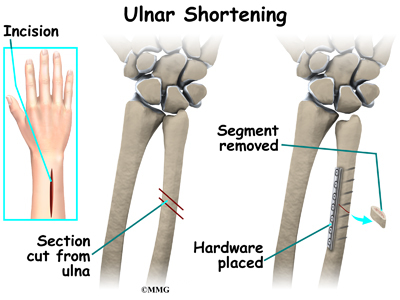

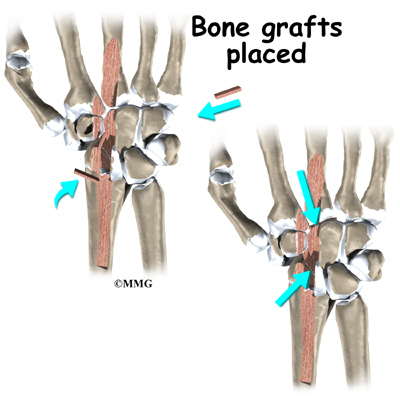

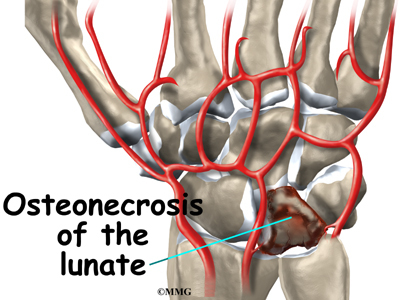

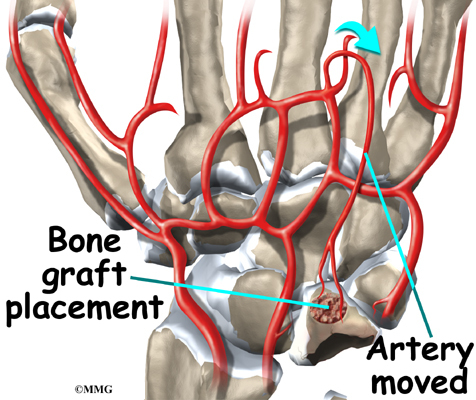

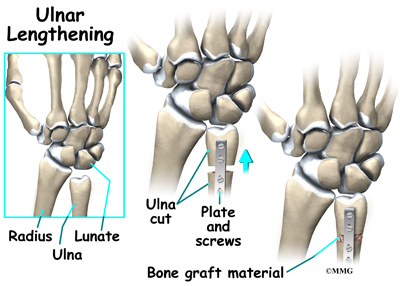

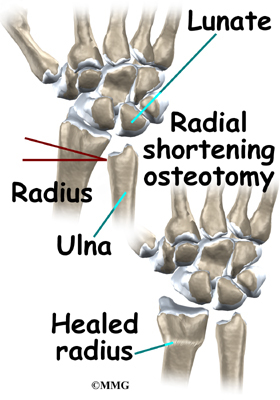

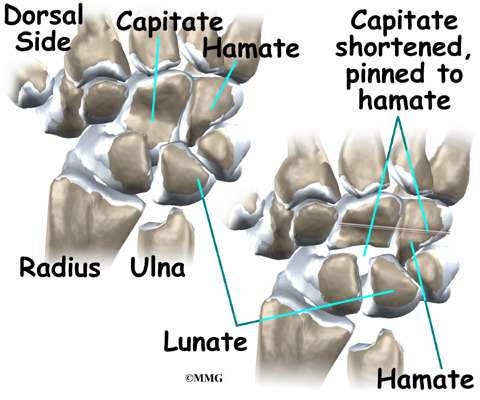

Chronic and degenerative TFCC may require a different surgical approach. Debridement is not as successful with this group as it is with acute TFCC injuries. Sometimes it is necessary to shorten the ulnar bone at the wrist to obtain pain relief. There are two procedures used to shorten the ulna and unload the ulnocarpal joint. These are the ulnar (diaphyseal) shortening method and the distal ulnar head shortening osteotomy (Feldon wafer method). If lunate-triquetrum instability is present, ulnar shortening can be done to tighten the ulnocarpal ligaments and decrease the motion between the lunate and triquetrum.

When making the decision as to which procedure, the surgeon weighs the amount of shortening needed and the conformation of the distal radioulnar joint. (DRUJ) – which will affect the joint loading.

Diaphyseal Shortening method (using internal fixation – plate/screws) – higher complication rate (delayed union, nonunion, hardware removal).

Distal Ulnar head shortening osteotomy (ie, Feldon wafer method) arthroscopic or open method (only 2-3mm of shortening ) – less invasive and equal relief to diaphyseal shortening

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Many patients with a mild triangular fibrocartilage complex injury are able to return to work and/or return to sports at a preinjury level. Pain-free movement and full strength are possible.

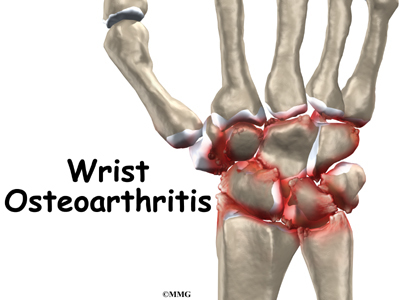

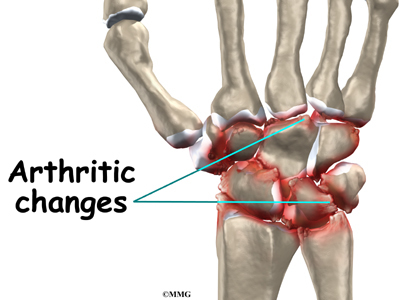

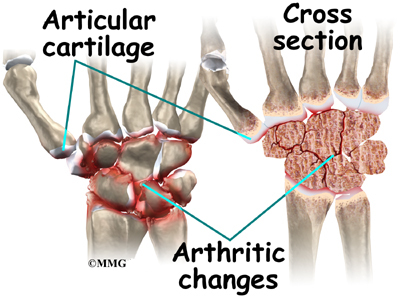

Residual laxity may remain after nonoperative treatment of a TFCC injury. If conservative care is unsuccessful, persistent joint laxity and instability can lead to degeneration of the articular cartilage. Too much force or compression on either side of the joint can lead to pain and altered movement patterns. Surgery may be needed to restore normal wrist movement.

After Surgery

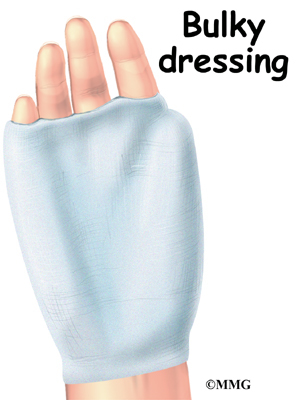

Your wrist will be immobilized in a bulky dressing or cast. The type of immobilizing device used and the position your wrist is placed in depends on the type of surgery you had. Motion exercises are usually started five to seven days after the operation.

Pain relief, improved motion, and increased function are the main goals of surgery for most patients. The surgeon is also interested in restoring wrist stability and the load bearing function of the wrist. After the initial soreness from the surgery is gone, you should experience a significant decrease in pain. Many patients report being pain free.

The follow-up plan after surgery may vary depending on the type of procedure used by your surgeon. Newer and improved methods have made it possible for some patients to return to full, unrestricted activity as early as six weeks post-op.

The standard result usually follows a typical course. One week after surgery, the splint will be replaced with a fiberglass type cast (still in a supinated position). The elbow is left free to move fully. The cast will be removed six weeks after the operation. Cast removal is followed by physical therapy for six to eight weeks.

Physical therapy may be needed to help you regain full joint motion, strength, and normal movement patterns. Some patients have difficulty regaining pinch and grip strength. The therapist will help you get back specific motions lost such as ulnar deviation (moving hand at the wrist away from the thumb and toward the little finger) and supination (palm up motion) or pronation (palm down motion). The therapist will help make sure you do not use compensatory shoulder motions to make up the difference.

The goal is to restore full motion, strength, and function. The rehab program will be geared toward your needs at home, work, and play. Many patients are able to return to work with no restrictions. A small number may require some work restrictions or changes in work tasks.

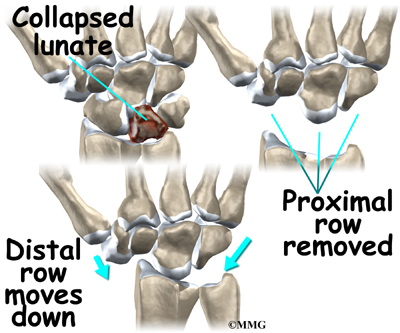

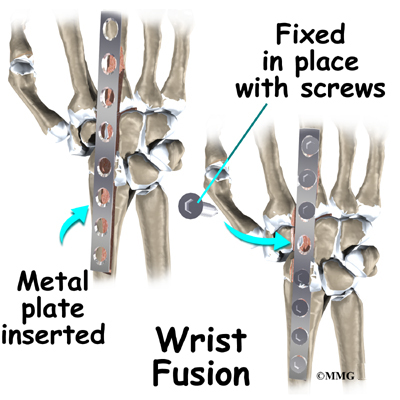

Complications may occur such as persistent pain and stiffness. Infection or delayed union or nonunion of bone fractures may be a problem. Further surgery may be needed to revise the first operation. Some patients need another surgery to remove any hardware used to stabilize the joint. The bottom of the ulna called the styloid may have to be removed. In rare cases, the procedure fails to provide the desired results. A wrist fusion may be the next step.