Cervical Spine

Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation (TENS) for Cervical Spine Pain

A Patient’s Guide to Transcutaneous Electrical Stimulation (TENS) for Cervical Spine Pain

Introduction

Neck (cervical spine) pain due to musculoskeletal disorders, is the second largest cause of time off work – low back pain being first. It is generally worse in the morning and evening. The most commonly prescribed intervention is rest and analgesics, and often a referral to physical therapy. Among the rehabilitation intervention treatments for neck pain is the transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit.

Electrical nerve stimulation is a treatment for pain that is used primarily for chronic pain. The electrical stimulation is delivered through electrodes or patches placed on the skin. The technique and the device used is called transcutaneous electrical stimulation or TENS for short.

TENS is a noninvasive way to override or block signals from the nerves to the spinal cord and brain. Pain messages may be altered enough to provide temporary or even long-lasting pain relief. Besides controlling pain, this type of electrical stimulation can also improve local circulation and reduce or eliminate muscle spasm.

This guide will help you understand

- who may benefit from a TENS unit

- how a TENS unit works

- what to expect with a TENS unit

Who may benefit from a TENS unit

TENS can be used for relief of pain associated with a wide variety of painful conditions. This may include back pain caused by spine degeneration, disc problems, or failed back surgery. Nerve pain from conditions such as chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS) and neuropathies caused by diabetes or as a side effect of cancer treatment may also be managed with TENS.

TENS has been used for people suffering from cancer-related pain, phantom-limb pain (a chronic pain syndrome following limb amputation), and migraine or chronic tension-type headaches.

TENS can also be used for muscle soreness from overuse, inflammatory conditions, and both rheumatoid and osteoarthritis. Athletes with painful acute soft tissue injuries (e.g., sprains and strains) may benefit from TENS treatment.

Sometimes it is used after surgery for incisional or post-operative pain from any type of surgery (e.g., joint replacement, cardiac procedures, various abdominal surgeries, cesaerean section for the delivery of a baby). Studies show that TENS can significantly reduce the use of analgesics (pain relievers, including narcotic drugs) after surgery.

TENS is usually used along with other forms of treatment and pain control such as analgesics, relaxation therapy, biofeedback, visualization or guided imagery, physical therapy and exercise, massage therapy, nerve block injections, and/or spinal manipulation.

The effectiveness of TENS remains controversial. The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) findings published in Dec. 30, 2009 issue of Neurology claims it is not effective and cannot be recommended. But, many patients find TENS effective for pain relief, easy to use, and with very low side effects. It may be worth a try for those who suffer from chronic low back pain. It can be discontinued easily if it doesn’t work. TENS cannot correct an underlying problem; it is only used for temporary relief of symptoms.

TENS is a noninvasive way to override or block signals from the nerves to the spinal cord and brain. Pain messages may be altered enough to provide temporary pain relief. Besides controlling pain, this type of electrical stimulation can also improve local circulation and reduce or eliminate muscle spasm.

To summarize, the benefits from TENS treatment can include:

- pain relief

- increased circulation and healing

- decreased use of pain relievers or other analgesic drugs

- increased motion and function

How does TENS work?

TENS produces an electrical impulse that can be adjusted for pulse, frequency, and intensity. The exact mechanism by which it works to reduce or even eliminate pain is still unknown. It is possible there are several different ways TENS works. For example, TENS may inhibit (block) pain pathways or increase of the secretion of the pain reducing substances (e.g., endorphins, serotonin) in the CNS.

Electrical nerve stimulation is a treatment for pain that is used primarily for chronic pain. The electrical stimulation is delivered through electrodes or patches placed on the skin. The technique and the device used is called transcutaneous electrical neurostimulation or TENS for short.

TENS is a noninvasive way to override or block signals from the nerves to the spinal cord and brain. Pain messages may be altered enough to provide temporary or even long-lasting pain relief. Besides controlling pain, this type of electrical stimulation can also improve local circulation and reduce or eliminate muscle spasm.

Recent research has also shown that autosuggestion or the placebo effect is a powerful way many people experience pain relief or improvement in symptoms. Simply by believing the treatment (any treatment, including TENS) will work has a beneficial effect on the nervous system. Many studies have shown that people get pain relief through the placebo effect alone.

How do I use my TENS unit?

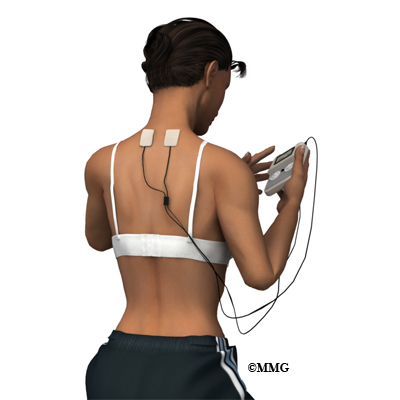

You will be shown how to use your TENS device by your healthcare provider trained in the set-up and use of this modality. Round or square rubber electrodes are applied to the skin over or around the painful area. Usually four electrodes (two pairs) are used to get maximum benefit from this treatment.

The electrodes are self-adhesive with a protective layer of gel built in to prevent skin irritation or burning. The unit is battery-operated with controls you manipulate yourself to alter the strength of the electrical signal. The unit can be slipped into a pocket or clipped to your belt. You may use two or four electrodes.

The electrodes will be placed on your body at positions selected by a physician or physical therapist. The electrode placement is determined based on the location of the involved nerves and/or the location of your pain.

The first place to try the electrodes is either directly over the painful area or on either side of the pain. You will slowly turn up the intensity of the unit until you feel a buzzing, tingling, or thumping sensation strong enough to override the pain signals.

If that doesn’t work, you may get better results putting the electrodes over the area where the spinal nerve root exits the vertebra. Sometimes it takes a bit of trial and error to find the right settings and best electrode placement for you.

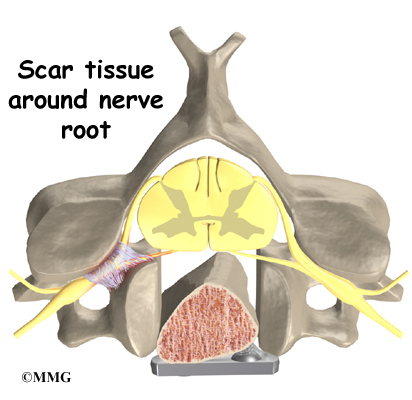

Be sure and let your healthcare provider know if you experience increased pain. Electrodes placed below the level of a peripheral nerve impairment might actually block the input from the TENS unit and cause increased pain. Or placement over an area of scar tissue from surgery can cause increased skin resistance and decreased transmission of the electrical impulses.

Another way to use TENS is over spots in the muscles that trigger pain called trigger points (TrPs). Trigger points are areas of hyperirritability in the muscles that can cause chronic pain. The healthcare provider will identify any TrPs present during your exam. Usually TrPs are taken care of with a treatment designed to eliminate them. In some patients they are chronic and don’t go away or come back easily. In such cases, TENS may be helpful.

Your health care team will guide you through the trial-and-error process for finding the best electrode placement for you and make any changes needed in the program.

When you should NOT use TENS

- If you have loss of skin sensation or even decreased sensation, you should not use TENS. With altered sensation, there is a risk of turning the unit up too high and causing injury or harm.

- The use of TENS is not recommended for older adults with Alzheimer’s, dementia, or other cognitive problems.

- If you have a cardiac pacemaker, you should not use TENS as the electrical signals could interfere with your pacemaker. Cardiac patients should not use TENS without their physician’s approval.

Some guidelines when using TENS

- Before applying the electrodes, it is important to remove all lotions, oils, or other applications to the skin. You may want to shave hair from the local area where the electrode will be applied.

- Daily use of TENS for several hours at a time is recommended. You should not wear the unit for long periods of time (e.g., 24 hours) or during extended sleep time (napping is okay but TENS should not be used while sleeping at night or for more than a couple of hours).

- Never place an electrode over an open wound or area of skin irritation. Report any skin problems or burns immediately.

- Do not place electrodes near your eyes or over your throat.

- Do not use TENS in the shower or bathtub.

- Move the electrodes a bit each time you put them on to avoid skin irritation.

- You should experience a comfortable tingling sensation that is comfortable enough to allow you to complete daily tasks and activities.

- You may want to keep a daily journal of your pain levels, the settings you use, and a record of the medications you are taking for pain relief. By reviewing your notes, you may find the best combination of electrode placement and unit settings that gives you the most pain relief.

What you can expect with TENS

You should feel a mild to moderately strong tingling or buzzing sensation. Some people experience a more unpleasant sensation described as burning or prickling. Depending on the intensity and duration of your pain, you may or may not get results right away.

It can take several days to even several weeks to get the desired results. Differences in results may occur based on properties of skin resistance, type of pain, and individual differences in the mechanism of pain control. Be patient and persistent. Do not hesitate to contact your healthcare provider as often as it takes to get the desired results.

Many patients do report good-to-excellent results, first with pain control, then pain relief, and finally reduction in the use of medications. Although it doesn’t happen for everyone, some chronic pain patients are “cured” permanently from their pain.

As each of these benefits from the TENS treatment occur, you may find yourself increasing your activity level – either with the same level of TENS usage or even with reduced frequency of use, intensity of signal, or duration (length of time the unit is turned on).

If for any reason your pain starts to increase in frequency, duration, or intensity, don’t assume the treatment isn’t working for you. First, check the TENS unit for any malfunction, need to recharge, or replace the electrodes with new ones. If your unit is battery-operated, you may find it necessary to turn the intensity up to obtain the same sensation when the batteries are low. This should alert you to the need for battery replacement.

Finally, be aware that some patients experience “breakthrough pain,” referring to a situation in which you get pain relief at first but then even with the TENS unit, you start to have pain once again. Turning the intensity up high enough to cause muscle contraction is an indication of breakthrough pain.

Sometimes a different setting for the stimulator may be needed when this happens. Most units have a setting that allows for random pulse frequency, duration, and amplitude. The use of this setting helps keep the nervous system from getting used to a specific amount of stimulation and ignoring it. This phenomenon is called habituation or adaptation.

Summary

TENS is an effective method of pain control for chronic pain when you want to maintain your normal routine of daily activities that would otherwise be hampered by too high of pain levels. TENS helps many people reduce and sometimes even eliminate the use of pain medications, thus avoiding side-effects of long-term drug use.

Even without complete pain relief, TENS makes it possible to stay active and participate in work, family, and even recreational activities. There are no significant adverse effects from the use of TENS. The ability of this treatment technique to moderate pain and reduce the use of pain medications is a real benefit — especially with the potential for serious or adverse effects from long-term use of pain relievers.

Cervical Burners and Stingers (Brachial Plexus Injuries)

A Patient’s Guide to Burners and Stingers (Brachial Plexus Injuries)

Introduction

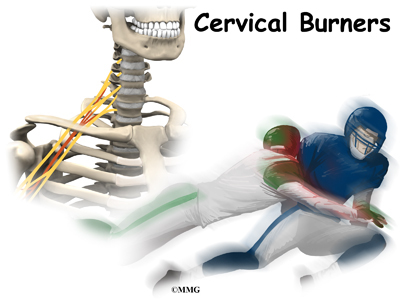

Injury to the nerves of the neck and shoulder that cause a burning or stinging feeling are called burners or stingers. Another name for this type of nerve injury is brachial plexus injury. Football players are affected most often. Up to half of all college football players have had at least one burner or stinger. Many of these occurred during high school football. Fortunately, it’s not a serious neck injury.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the body are involved

- how the problem develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

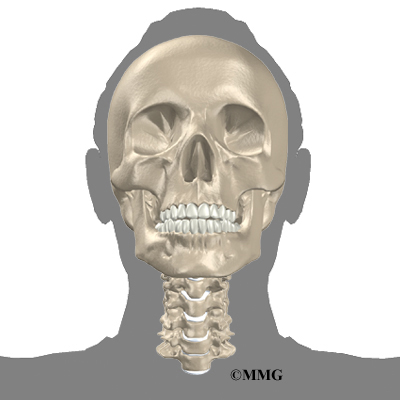

What parts of the body are involved?

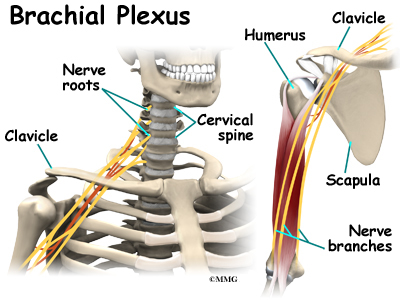

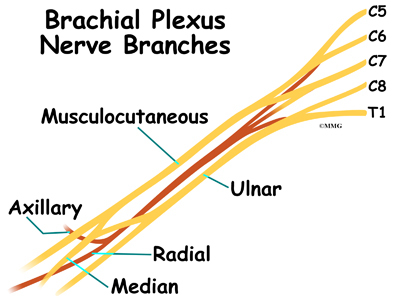

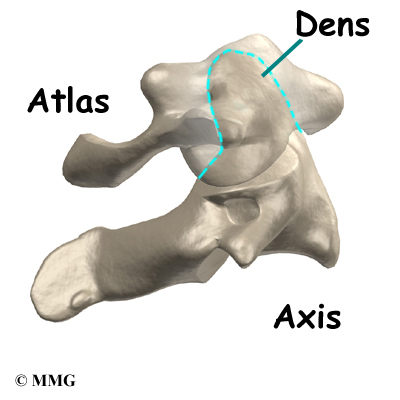

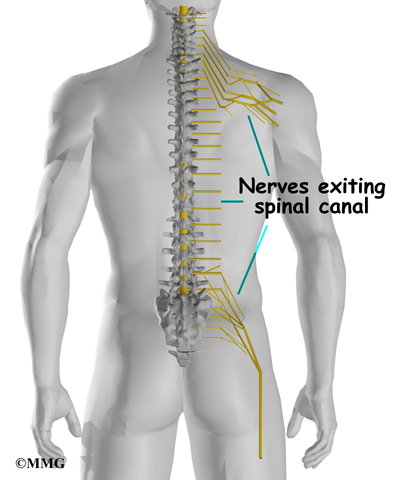

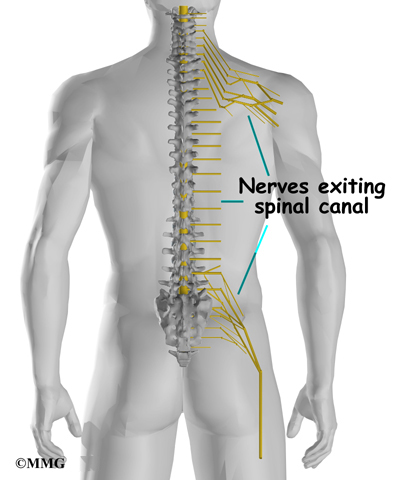

The brachial plexus is affected most often by a downward or backward force against the shoulder. A nerve plexus is an area where nerves branch and rejoin. The brachial plexus is a group of nerves in the cervical spine from C5 to C8-T1. This includes the lower half of the cervical nerve roots and the nerve root from the first thoracic vertebra.

The nerves leave the spinal cord, go through the neck, under the clavicle

(collar bone) and armpit, and then down the arm.

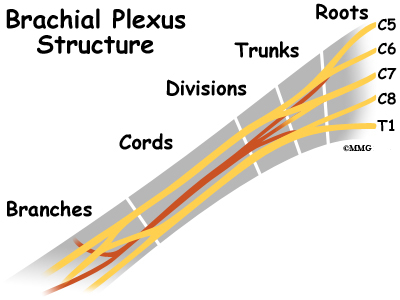

The brachial plexus begins with five roots that merge or join together to form three trunks. The three trunks are upper (C5-C6), middle (C7), and lower (C8-T1). Each trunk then splits in two, to form six divisions. These divisions then regroup to become three cords (posterior, lateral, and medial).

Finally, there are branches that result in three nerves to the skin and muscles of the arm and hand: the median, ulnar, and radial nerves.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Cervical Spine Anatomy

Causes

What causes this condition?

Burners or stingers are the result of traction or compressive forces on the brachial plexus or cervical nerve roots. The usual mechanism of injury occurs when a direct blow or hard hit to the top of your shoulder pushes it down at the same time your head is forced to the opposite side.

In the process, the brachial plexus between the neck and shoulder gets stretched. The same injury can happen if a downward force hits the collarbone directly. In football, burners or stingers occur most often when you tackle or block another player. This motion overstretches the nerves of the brachial plexus.

It’s not clear exactly where in the brachial plexus the damage occurs. Some experts suggest the injury is most likely to be at the level of the trunks, rather than at the nerve root level. The results of other studies show that burners or stingers from compression forces cause nerve root damage while traction injuries result in plexus injuries. A nerve root injury would be much more serious than a burner or stinger from a trunk injury of the brachial plexus.

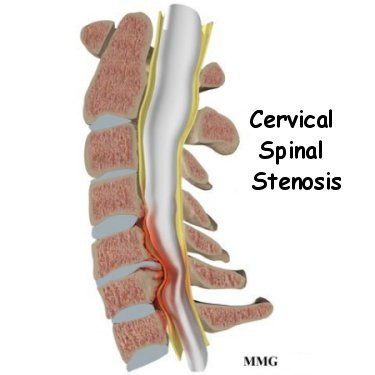

Other athletes who participate in wrestling, gymnastics, snow skiing, and martial arts can also experience burners or stingers. Some studies suggest that athletes with a narrow cervical canal may be at increased risk for this type of injury.

Symptoms

What does this condition feel like?

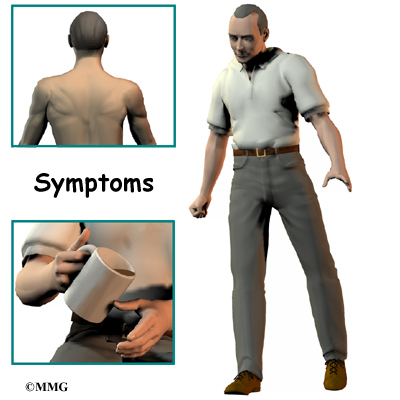

A burning or stinging feeling between the neck and shoulder is the hallmark finding in this condition. True neck pain is more likely to be an injury to the neck itself. With burners or stingers, the painful symptoms start above the shoulder and go down the arm and even into the hand.

The shoulder and arm may feel numb or weak. You may feel as if this area is tingling. Weakness may be present at the time of the injury. Some patients report the arm feels and appears to be “dead”. This paralysis and other symptoms may be transient or temporary. They may only last a few seconds or minutes. But for some patients, healing takes days or weeks. In rare cases, the damage can be permanent.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose this condition?

A careful history and physical exam are needed to diagnose stingers or burners. By assessing areas of weakness, the examiner may be able to tell whether a stretch injury of the brachial plexus has occurred. Nerve function and reflexes are also evaluated. If the physician suspects a cervical spine injury, further testing may be needed.

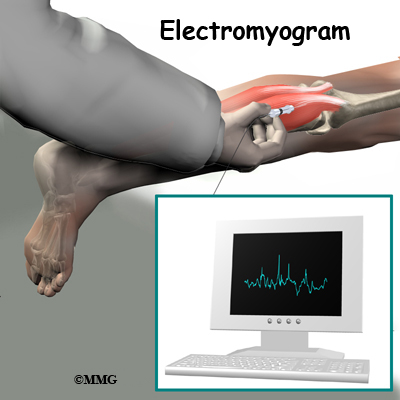

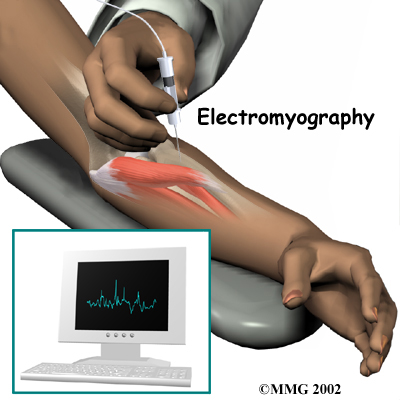

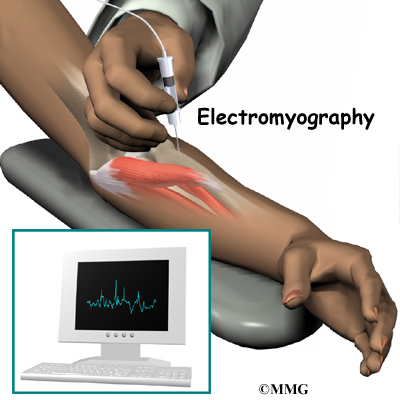

X-rays, MRI, and electrodiagnostic studies such as an electromyogram (EMG) can help make the final diagnosis. The EMG will confirm a problem, pinpoint the area of damage, and give an idea of how long recovery will take for each individual.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

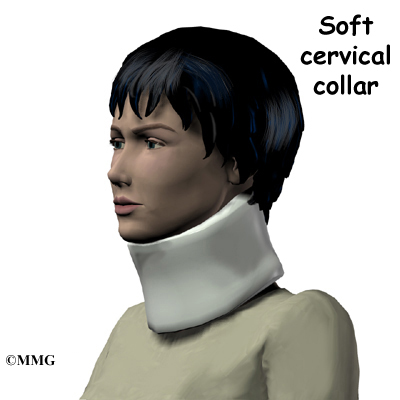

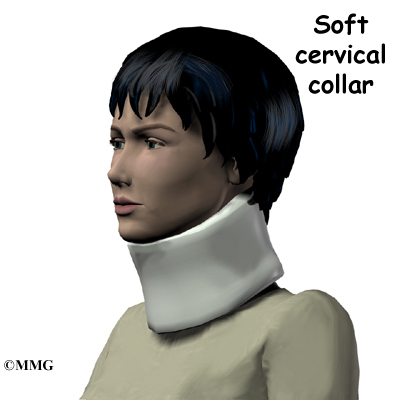

Protecting the neck with a soft collar is the first step in the acute phase of burners or stingers. If the injury occurs on the playing field, the player is placed in a protective collar before being moved off the field. This is worn until X-rays are taken to rule out fracture, dislocation, or other more serious neck injury.

Rest and gentle neck and shoulder range of motion are advised until symptoms resolve. If this does not occur within a few days, then physical therapy may be needed. Your therapist will use modalities such as biofeedback, electrical nerve stimulation, and manual therapy to help restore the natural function of the nerves.

Range of motion and strengthening exercises will be added as tolerated. Posture is very important during the healing phase. A chest-out position helps open the spinal canal, thus giving more room for the spinal cord. This posture also decreases pressure on the nerve roots. Your therapist will provide sport-specific therapy when the symptoms resolve (go away).

Surgery

Surgery is not a treatment option for burners or stingers. Management remains conservative (nonsurgical). Patients are followed through the athletic season until recovery is complete.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Burners and stingers are self-limiting. This means that with treatment, they will resolve over time. You will likely be able to return to full sports participation when you no longer have any symptoms. Full neck and shoulder motion must be present. And you should be able to participate in practice without any problems before entering a game.

It is possible to get another burner or stinger but it could be something more serious. If you experience these types of symptoms again, slowly lie down on the ground. Wait for the team trainer or physician to examine you before moving your head and neck.

Some football players choose to wear extra padding, special shoulder pads, or a neck roll to protect the neck and avoid reinjury. All equipment should be in good condition and fit properly. Daily stretching of the neck is advised. Players should avoid using spearing or head tackling, which has been prohibited since 1979.

Dropped Head Syndrome

A Patient’s Guide to Dropped Head Syndrome

Introduction

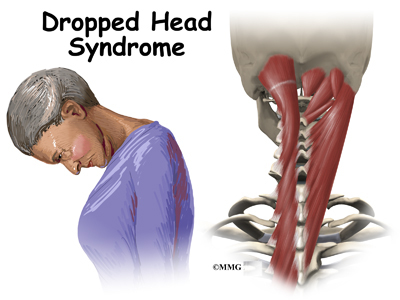

Dropped Head Syndrome is characterized by severe weakness of the muscles of the back of the neck. This causes the chin to rest on the chest in standing or sitting. Floppy Head Syndrome and Head Ptosis are other names used to describe the syndrome.

Most of the time, Dropped Head Syndrome is caused by a specific generalized neuromuscular diagnosis. When the cause is not known, it is called isolated neck extensor myopathy, or INEM.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the cervical spine

- what causes this condition

- how doctors diagnose this condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts make up the cervical spine?

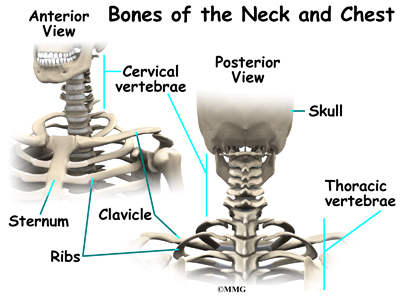

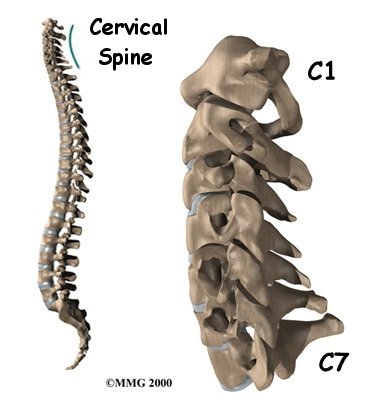

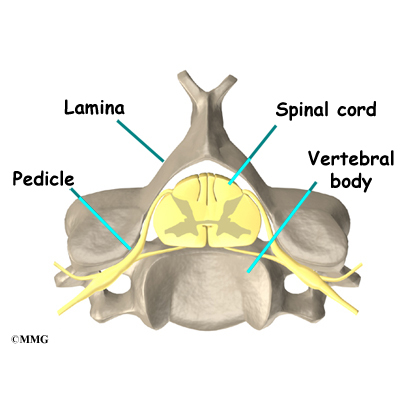

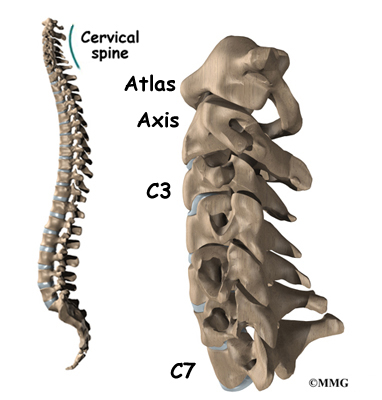

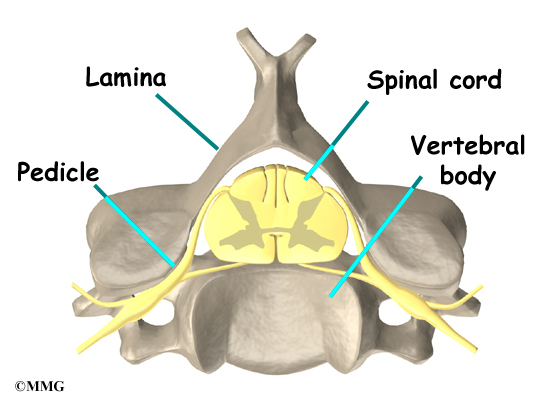

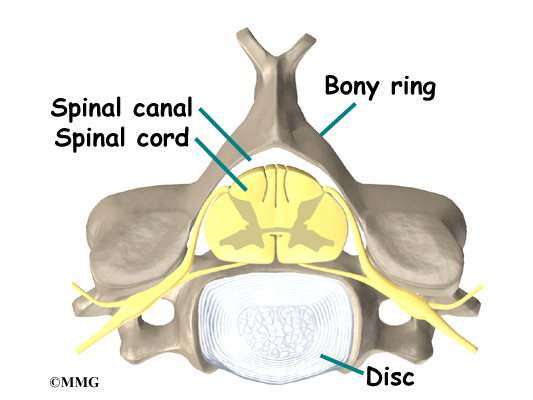

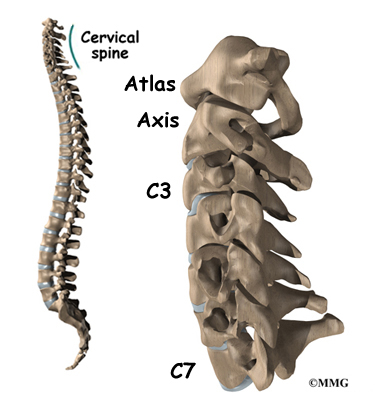

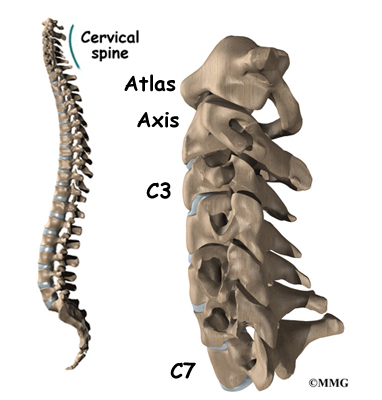

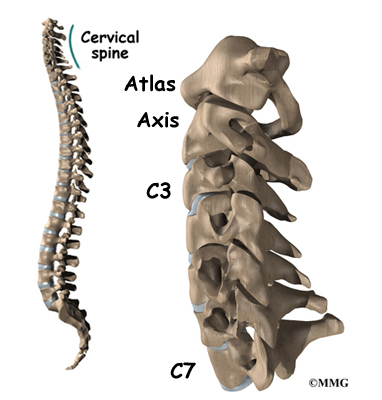

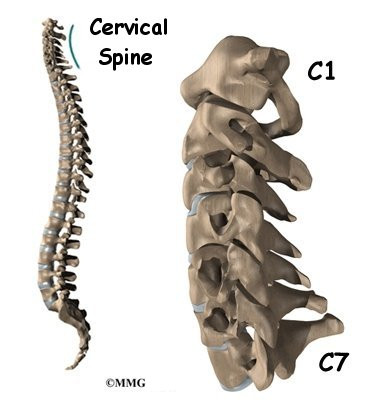

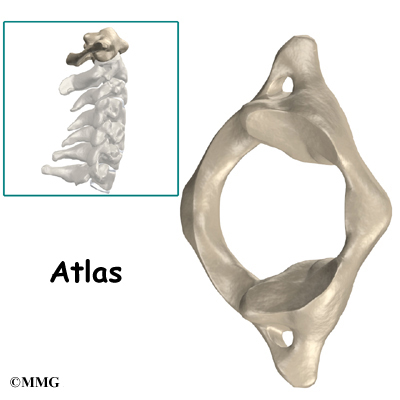

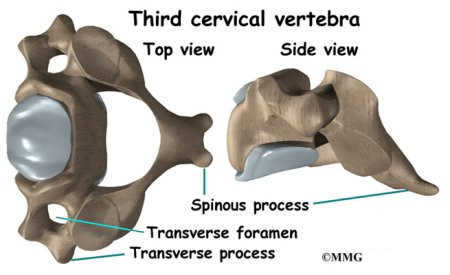

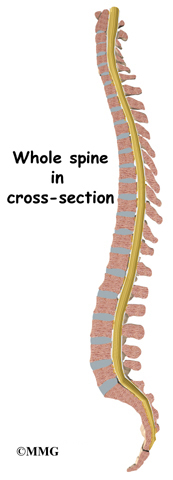

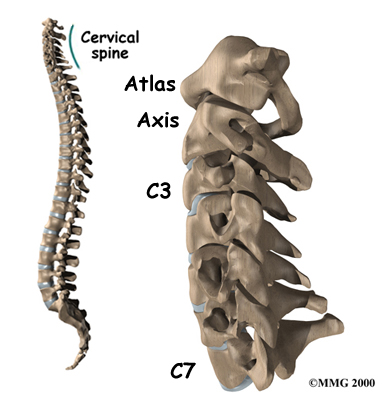

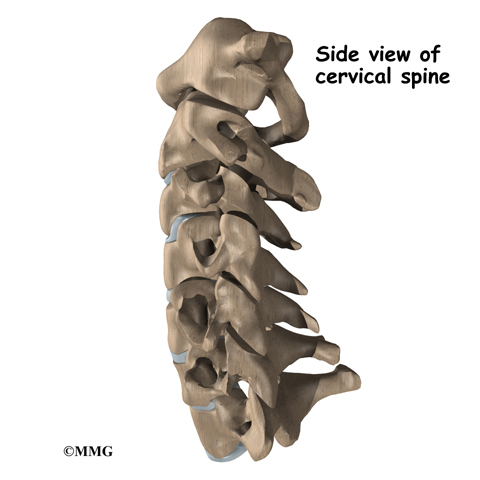

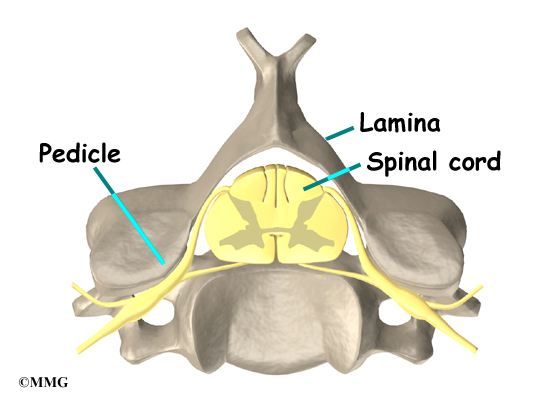

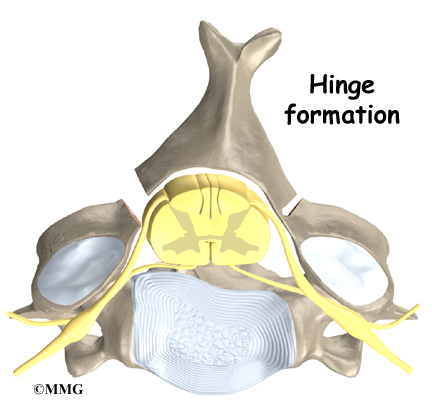

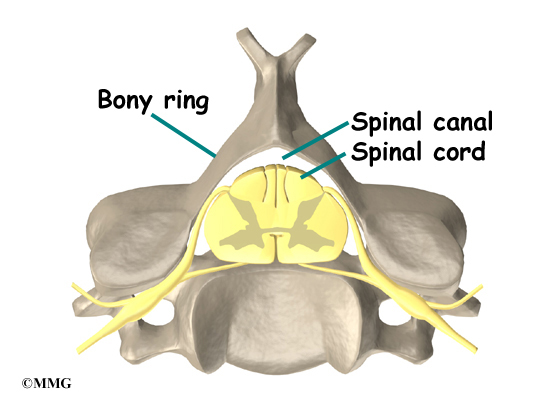

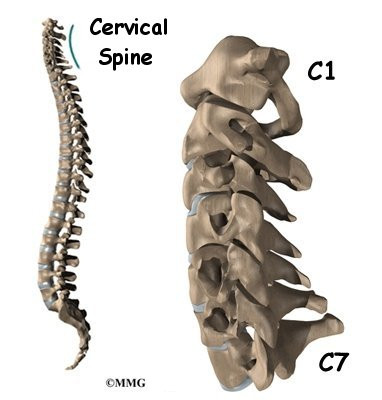

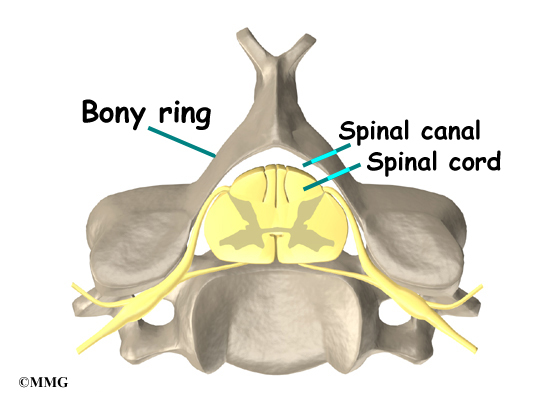

The spine is made up of a column of bones. Each bone, or vertebra, is formed by a round block of bone, called a vertebral body. A bony ring attaches to the back of the vertebral body, forming a canal for the spinal cord. The spinal cord is a made up of nerve cells which grow to look like a rope or cord about one half inch in diameter. The spinal cord attaches to the base of the brain. The base of the brain is called the

brainstem.

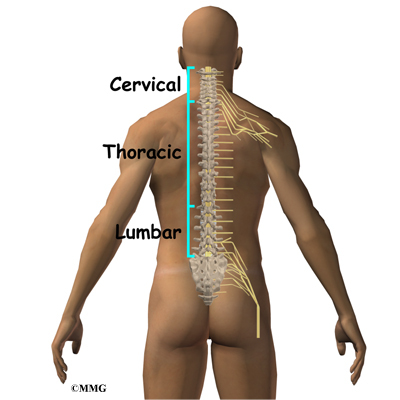

The vertebral column is divided into three distinct portions. The cervical, or neck portion attaches to the base of the skull at the upper end. The lower end of the cervical portion connects with the thoracic spine. There are seven cervical vertebrae.

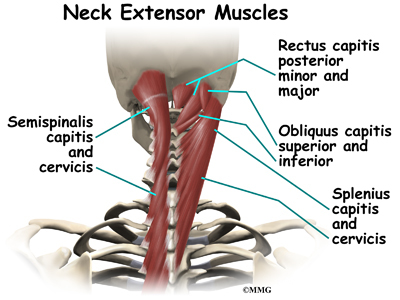

There are many muscles that lie in the neck region. Some attach from the base of the skull, others to the spine, ribs, collar bone, and shoulder blade. Extension of the neck happens when the top of the head tilts backward. This causes the face and eyes to look up. Flexion of the neck is when the top of the head tilts forward. This causes the eyes to look down. It also lowers the chin to the chest.

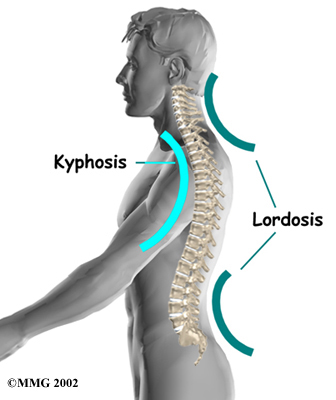

The vertebrae stack on top of one another. When looking at the spine from the side, or from the sagittal view, the vertebral column is not straight up and down, but forms an “S” curve. The cervical spine has an inward curve called a lordosis. The thoracic spine curves outward. This curve is called a kyphosis. The lumbar spine usually has an inward curve or a lordosis. The “S” curve seen in the sagittal or side view allows for shock-absorption and acts as a spring when the spine is loaded with weight.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Cervical Spine Anatomy

Causes

What causes this condition?

Most of the time, Dropped Head Syndrome is caused by a specific generalized neuromuscular diagnosis. These include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, myasthenia gravis, polymyositis, and genetic myopathies. Other specific causes can include motor neuron disease, hypothyroidism, disorders of the spine, and cancer.

When the cause of Dropped Head Syndrome is not known, it is called isolated neck extensor myopathy, or INEM.

The INEM form of Dropped Head Syndrome usually happens in older persons. The weakness of the muscles in the back of the neck usually occurs gradually over one week to three months.

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

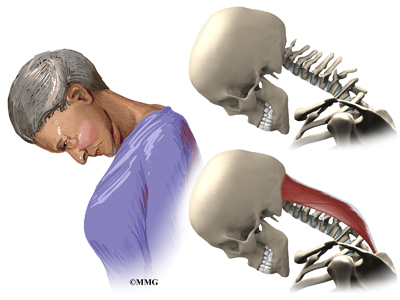

The symptoms of dropped head syndrome are usually painless. It most often occurs in the elderly. The weakness is limited to the muscles that extend the neck. Dropped Head Syndrome usually develops over a period of one week to three months. The head is then tilted downward. Because of the weakness of the extensors of the neck, the chin rests on the chest. Lifting or raising the head in sitting or standing is impossible. When lying down however, the neck is able to extend.

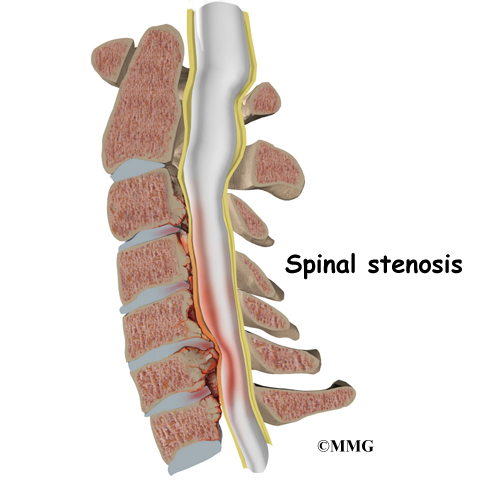

Gaze is down at the floor, instead of forward. The face is downward. The neck appears elongated, and the curve at the base of the neck is accentuated. This can cause over stretching or pinching of the spinal cord. When this happens, there may be weakness and numbness of the arms or entire body.

Dropped head syndrome can also cause difficulty swallowing, speaking, and breathing.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

Diagnosis begins with a complete history and physical exam. Your doctor will ask questions about your symptoms and how your problem is affecting your daily activities.

Your doctor will do a physical examination to test your reflexes, skin sensation, muscle strength.

Most of the time, loss of of neck extension occurs as part of a more generalized neurological disorder. Neurological conditions must be considered first because some are treatable. A neurologist will usually be involved to help decide what is causing the chin-on-chest deformity.

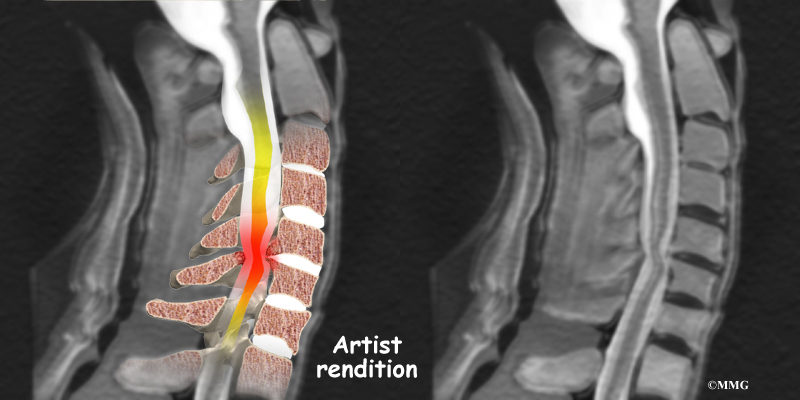

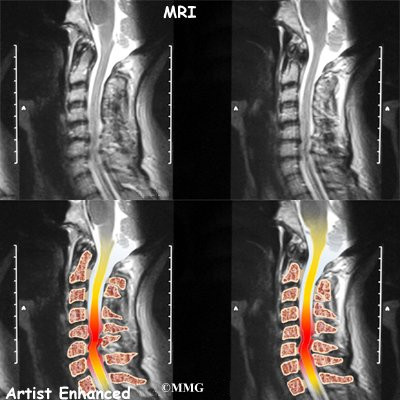

Your doctor will likely ask that you have magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of your neck. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than X-rays. It shows the anatomy of the neck. It is very good at showing the spinal cord and nerves. The test does not require a dye or a needle.

Electromygraphy (EMG) uses small diameter needles in the muscle belly being tested. It helps determine how well the nerve conducts signals to the muscles.

A muscle biopsy may be needed. A small piece of muscle is removed and examined under a microscope. A closer look at the muscle fibers can be helpful in making a diagnosis.

In isolated neck extensor myopathy (INEM), the muscle biopsy is non-specific. EMG shows some myopathic changes. Labs are normal.

If no other associated neurologic disorders are found, then the diagnosis of isolated neck extensor myopathy (INEM) is made. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, meaning that everything else that could caused it has been ruled out. It is not known what causes isolated neck extensor myopathy (INEM).

Some doctors feel that isolated neck extensor myopathy (INEM) is caused by either a non-specific non-inflammatory or inflammatory response that is restricted to the neck extensor muscles. Another possible cause is thoracic kyphosis. When the natural curve of the thoracic spine is increased, it may place the extensor muscles at a disadvantage given the weight of the head. This may cause over stretching and weakness of the extensor muscles.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Isolated neck extensor myopathy (INEM) is considered benign because it does not spread or get worse. Symptoms can improve in some cases. It is most often treated conservatively.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment of Dropped Head Syndrome is mainly supportive. The weakness remains localized to the neck extensor muscles, physical therapy may help with this. There are some cases that improve dramatically, but most usually do not improve.

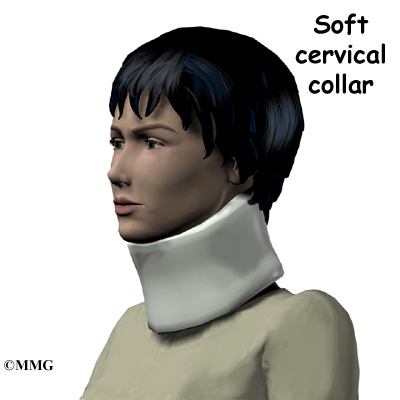

The most useful treatment is use of a neck collar. It can partially correct the chin-on-chest deformity. This improves the forward gaze and activities of daily living. It also can help prevent contractures of the neck in a fixed flexed posture. However, it can be uncomfortable and cause sores under the chin. Some use a baseball cap attached to straps around the trunk. This avoids the chin discomfort from using a collar.

Prednisone is a potent anti-inflammatory that may be prescribed. It may be beneficial when there is local myositis, or inflammation of the muscles. It can be taken in a pill form by mouth or intravenously.

Surgery

Unless fusion is necessary, surgery is usually not recommended in Dropped Head Syndrome.

When there is damage to the nerves in the neck or spinal cord, surgery to fuse the neck may be necessary. This usually requires a fusion from C2-T2. The loss of neck movement after fusion leaves patients unable to see the ground in front of their feet. This makes them at greater risk for falls. The inconvenience caused by having a rigid neck may prove to be a greater problem than the original dropped head deformity.

Osteoporosis, particularly in older females also poses a problem with surgery. The soft bone may allow the metal used to stabilize the spine to pull out.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect as I after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is usually recommended. Neck extension strengthening exercises may provide some improvement. However, most patients will find the strengthening both tiring and frustrating. When lying down on your back you can move the neck to maintain range of motion. This helps to avoid unnecessary stiffness and shortening of the muscles in the front of the neck.

Range of motion exercises should be done on an ongoing basis to avoid contractures of the neck. Wearing a neck collar when up will likely improve activities of daily living.

Speech therapy may be recommended for swallowing, feeding, and breathing problems. Some people may need to have a feeding tube inserted through the stomach.

Your doctor may want to repeat imaging of the spine. There is the possibility of over stretching or pinching the spinal cord when the neck extensors are so weak. You will need to watch for symptoms such as weakness or numbness in the arms or other portions of the body. Bowel and bladder function could become a problem.

After Surgery

If surgery is recommended, you will probably require an overnight hospital stay or a few days stay. Initially, you will not be allowed to lift, and you will have to move carefully. Most likely your neck will be placed in a fairly rigid brace. You will eventually be able to resume your normal activities. You can expect healing of the fusion in three to nine months.

Physical therapy is usually recommended after surgery. Neck extension strengthening exercises are prescribed to prevent contracture of the neck. Occupational therapy may be recommended to help with arm strengthening. It can also help with dressing, and other activities of daily living. Equipment needs can be evaluated by the occupational therapist. Speech therapy may also be recommended after surgery.

Your surgeon will want to follow up with you on a regular basis. Imaging studies may need to be repeated on occasion. Assessment of the fusion is usually done with X-rays.

Whiplash

A Patient’s Guide to Whiplash

Introduction

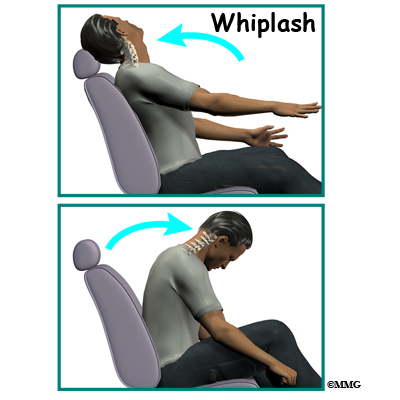

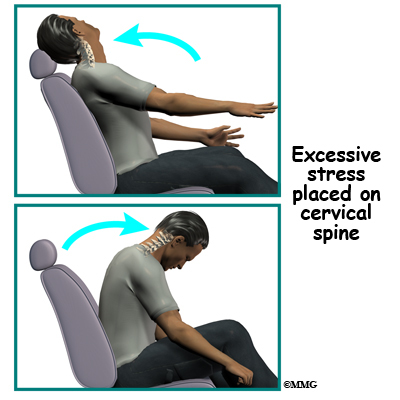

Whiplash is defined as a sudden extension of the cervical spine (backward movement of the neck) and flexion (forward movement of the neck). This type of trauma is also referred to as a cervical acceleration-deceleration (CAD) injury. Rear-end or side-impact motor vehicle collisions are the number one cause of whiplash with injury to the muscles, ligaments, tendons, joints, and discs of the cervical spine.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the spine and neck

- what causes this condition

- how doctors diagnose this condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the spine are involved?

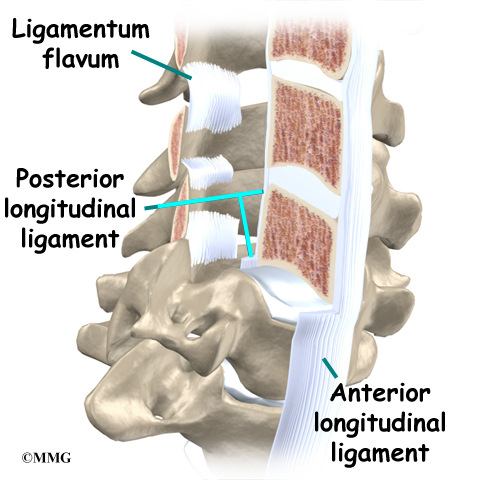

The human spine is made up of 24 spinal bones, called vertebrae. Vertebrae are stacked on top of one another to form the spinal column. The spinal column is the body’s main upright support.

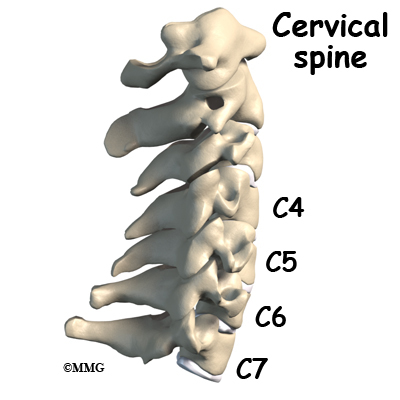

The cervical spine is formed by the first seven vertebrae referred to as C1 to C7. The cervical spine starts where the top vertebra (C1) connects to the bottom edge of the skull. The cervical spine curves slightly inward and ends where C7 joins the top of the thoracic spine. This is where the chest begins.

A bony ring attaches to the back of the vertebral body. When the vertebrae are stacked on top of each other, the rings form a hollow tube. This bony tube surrounds the spinal cord as it passes through the spine. Just as the skull protects the brain, the bones of the spinal column protect the spinal cord.

As the spinal cord travels from the brain down through the spine, it sends out nerve branches between each vertebrae called nerve roots. The nerve roots that come out of the cervical spine form the nerves that go to the arms and hands.

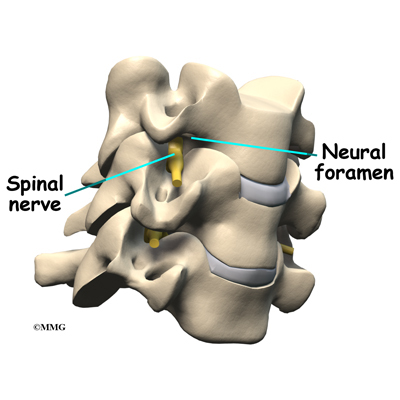

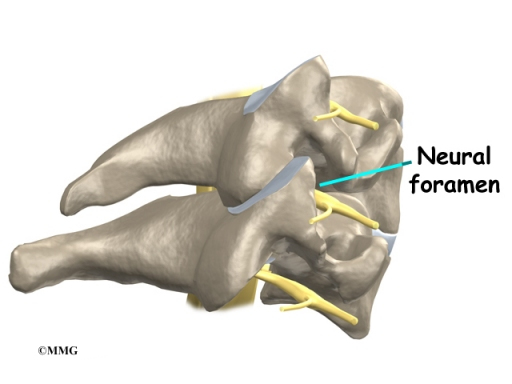

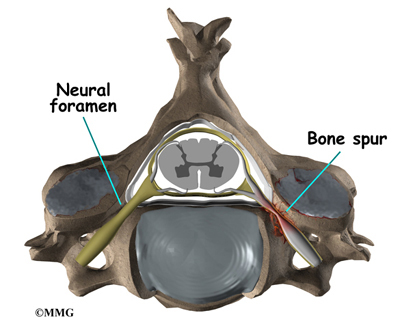

Two spinal nerves exit the sides of each spinal segment, one on the left and one on the right. As the nerves leave the spinal cord, they pass through a small bony tunnel on each side of the vertebra, called a neural foramen. (The term used to describe more than one opening is neural foramina.)

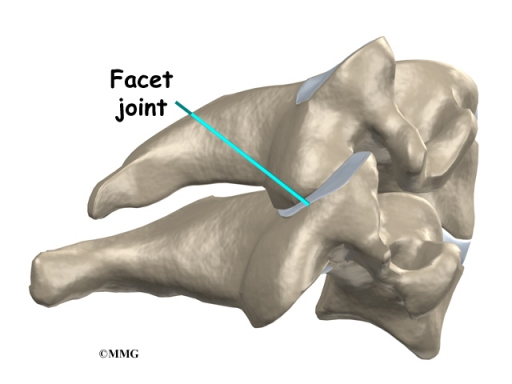

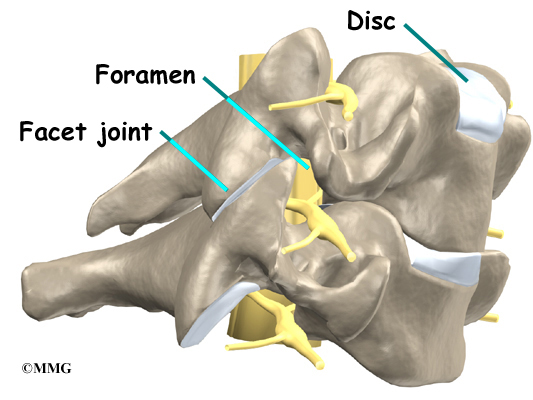

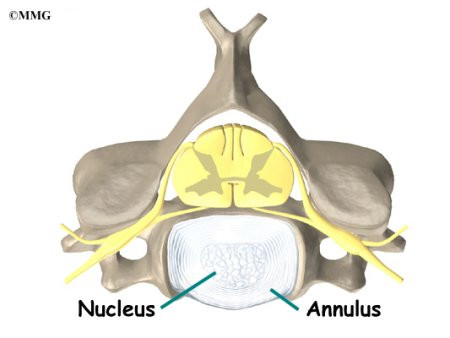

Each spinal segment includes two vertebrae separated by an intervertebral disc, the nerves that leave the spinal cord at that level, and the small facet joints that link each level of the spinal column.

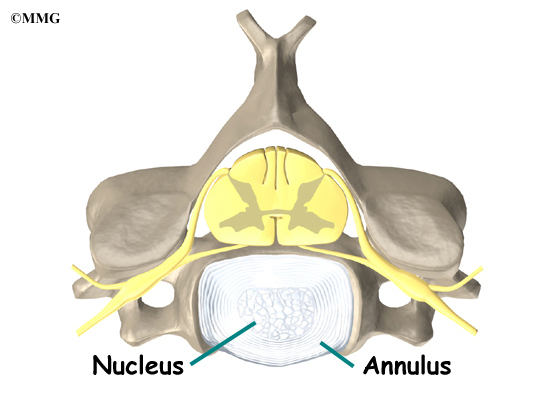

An intervertebral disc is made of connective tissue. Connective tissue is the material that holds the living cells of the body together. The disc is a specialized connective tissue structure that separates the two vertebral bodies of the spinal segment. The disc normally works like a shock absorber. It protects the spine against the daily pull of gravity. It also protects the spine during activities that put strong force on the spine, such as jumping, running, and lifting.

An intervertebral disc is made up of two parts. The center, called the nucleus, is spongy. It provides most of the ability to absorb shock. The nucleus is held in place by the annulus, a series of strong ligament rings surrounding it. Ligaments are strong connective tissues that attach bones to other bones.

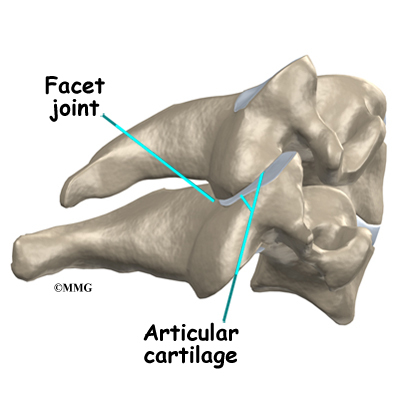

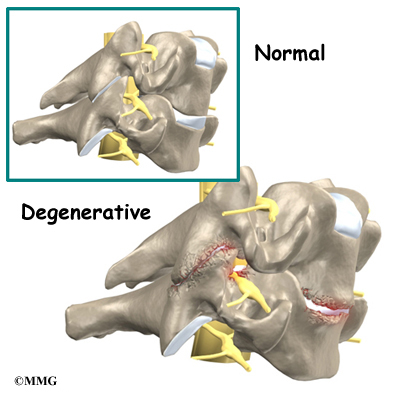

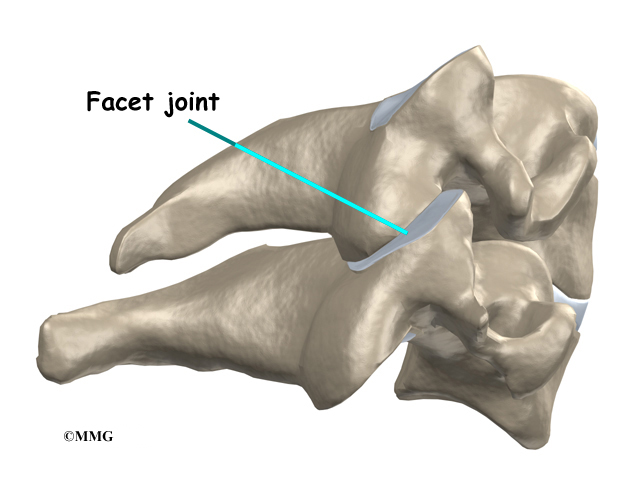

There are two facet joints between each pair of vertebrae–one on each side of the spine. The surfaces of the facet joints are covered by articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is a smooth, rubbery material that covers the ends of most joints. It allows the bone ends to move against each other smoothly, without pain. The alignment of the facet joints of the cervical spine allows freedom of movement as you bend and turn your neck.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Cervical Spine Anatomy

Causes

What causes this condition?

When the head and neck are suddenly and forcefully whipped forward and back, mechanical forces place excessive stress on the cervical spine. Traumatic disc rupture and soft tissue damage can occur.

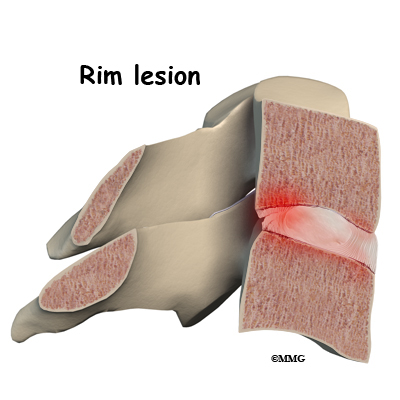

The cartilage between the disc and the vertebral bone is often cracked. This is known as a rim lesion.

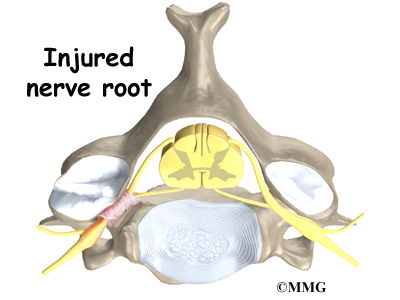

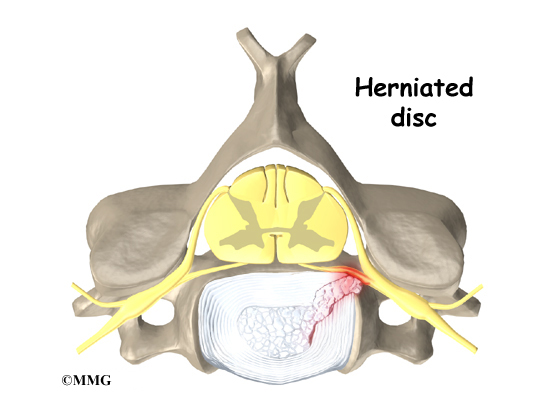

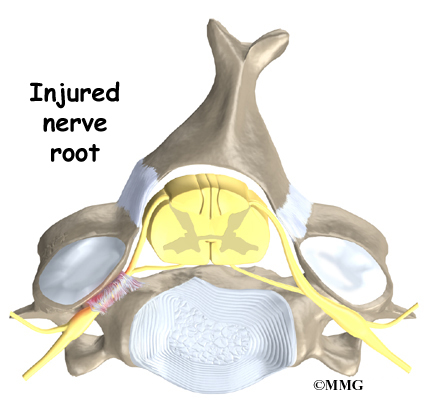

Damage to the disc can put pressure on the nerves as they exit the spine. The pressure or irritation can be felt as numbness on the skin, weakness in the muscles, or pain along the path of the nerve. Most people think of these symptoms as indications of a pinched nerve. Health care providers call this condition cervical radiculopathy.

Soft tissue around the facet joint can be injured. Many of the pain-sensing nerves of the spine are in the facet joints. The normally smooth surfaces on which these joints glide can become rough, irritated, and inflamed. Studies show that neck pain often comes from the damaged facet joints.

Low back pain is a common feature after a whiplash injury. Studies show that there is significant electrical activity in the muscles of the lumbar spine when the neck is extended. This effect increases when there is neck pain, possibly as a way to help stabilize the spine when neck pain causes weakness.

More than anyplace else in the body, the muscles of the neck sense sudden changes in tension and respond quickly. Tiny spindles in the muscles signal the need for more muscle tension to hold against the sudden shift in position.

The result is often muscle spasm as a self-protective measure. The increased muscle tone prevents motion of the inflamed joint. You may experience neck stiffness as a result.

Risk Factors

Each year, about three million people experience whiplash injuries to their neck and back. Of these three million people, only about one-half, will fully recover. About 600,000 of those individuals will have long-term symptoms, and 150,000 will actually become disabled as a result of the injury.

There are many factors that come into play when a person is injured in a rear-end motor vehicle accident. Any one or more of the following factors can affect recovery:

- Head turned one way or the other at the time of the impact (increases risk of nerve

involvement with pain down the arm) - Getting hit from behind (rear-impact collision)

- Previous neck pain or headaches

- Previous similar injury

- Being unaware of the impending impact

- Poor posture at the time of impact (head, neck, or chest bent forward)

- Poor position of the headrest or no headrest

- Crash speed under 10 mph

- Being in the front seat as opposed to sitting in the back seat of the car

- Collision with a vehicle larger than yours

- Being of slight build

- Wearing a seatbelt (a seat belt should always be worn, but at lower speeds, a lap and shoulder type seat belt will increase the chances of injury)

Symptoms

What are some of the symptoms of whiplash?

- Neck pain or neck pain that travels down the arm (radiculopathy)

- Headaches

- Low back pain (LBP)

- Jaw pain

- Dizziness

Ninety percent of patients involved in whiplash type accidents complain of neck pain. This is by far the most common symptom. The pain often spreads into the upper back, between the shoulder blades, or down the arm. Neck pain that goes down the arm is called radiculopathy.

Low back pain (LBP) can occur as a result of a whiplash injury. The Insurance Research Council reports that LBP occurs in 39 per cent of whiplash patients. Some studies found LBP to be present in 57 per cent of rear-impact collisions in which injuries were reported and 71 per cent of side-impact collisions.

Jaw pain as a result of temporomandibular joint (TMJ) injury can also cause painful headaches. The TMJ is formed by the bone of the mandible (lower jaw) connecting to the temporal bone at the side of the skull. The TMJ is a hinge joint that allows the jaw to open and close and to move forward, back, and sideways. Pain in this joint in called temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD).

Dizziness is quite common with a sense of lost balance being reported. It is caused by an injury to the joints of the neck called facet or zygapophyseal joints. When dizziness is reported, it should be distinguished from vertigo (also known as benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV), which results from an injury to the inner ear.

Other symptoms often reported include, but are not limited to: shoulder pain; numbness or tingling in the arms, hands, legs or feet; facial pain, fatigue, confusion, poor concentration, irritability, difficulty sleeping, forgetfulness, visual problems, and mood disorders.

It is not uncommon to have a delay in your symptoms. It is actually more common to have a 24 to 72 hour delay as opposed to immediate symptoms or pain. This is most likely due to the fact that it takes the body 24 to 72 hours to develop inflammation. Disc injuries may take even longer to manifest themselves. It is not uncommon for a disc injury to remain pain free and unnoticed for weeks to months.

Simply because there is little or no damage to your car does not mean that you were not injured. In fact, more than half of all whiplash injuries occur where there was little or no damage to one or both of the vehicles involved.

When we see visible damage to a car, it means that the car has absorbed much of that force and less force is transmitted to the occupant. On the other hand, if there is little or no damage to the car, the force is not absorbed but transferred to the driver or passengers, potentially resulting in greater injury.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the problem?

The diagnosis of neck problems begins with a thorough history of your condition and the involved car accident. You might be asked to fill out a questionnaire describing your neck problems. Then your doctor will ask you questions to find out when you first started having problems, what makes your symptoms better or worse, and how the symptoms affect your daily activity. Your answers will help guide the physical examination.

Your doctor will then physically examine the muscles and joints of your neck. It is important that your doctor see how your neck is aligned, how it moves, and exactly where it hurts.

Your doctor may do some simple tests to check the function of the nerves. These tests measure your arm and hand strength, check your reflexes, and help determine whether you have numbness in your arms, hands, or fingers.

The information from your medical history and physical examination will help your doctor decide which tests to order. The tests give different types of information.

Radiological Imaging

Radiological imaging tests help your doctor see the anatomy of your spine. There are many kinds of imaging tests including:

- X-rays

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

- Computed tomography (CT)

- Digital motion x-ray (DMX)

- Myelogram

- Bone Scan

- Electromyogram

X-rays

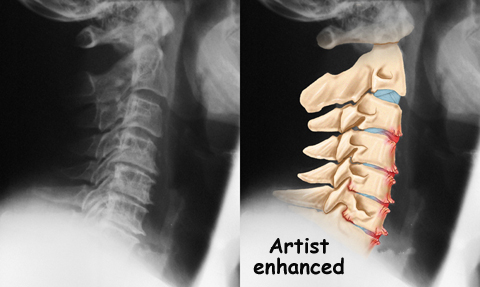

X-rays show problems with bones, such as infection, bone tumors, or fractures. X-rays of the spine also can give your doctor information about how much degeneration has occurred in the spine, such as the amount of space in the neural foramina and between the discs.

X-rays are usually the first test ordered before any of the more specialized tests. Special x-rays called flexion/extension x-rays may help to determine if there is instability between vertebrae. These x-rays are taken from the side as you bend as far forward and then as far backward as you can. Comparing the two x-rays allows the doctor to see how much motion occurs between each spinal segment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

If more information is needed, your doctor may order an MRI. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves rather than x-rays to create pictures of the cervical spine in slices. MRIs show the cervical spine vertebrae, as well as the soft tissue structures, such as the discs, joints, and nerves. MRI scans are painless and don’t require needles or dye. MRI scan has become the most common test to look at the cervical spine after x-rays have been taken.

Computed Tomography (CT)

CT scan is a special type of x-ray that lets doctors see slices of bone tissue. The machine uses a computer and x-rays to create these slices. It is used primarily when problems are suspected in the bones.

Digital motion x-ray (DMX)

DMX is a new fluoroscopic based x-ray system designed to objectively detect and document soft tissue/ligament injury most commonly associated with whiplash injuries of the spine. DMX evaluates biomechanical relationships and abnormal movements of the cervical spine. Specifically, DMX:

- Shows abnormal movement of vertebral bodies, facets, and other spinal elements

- Shows joint hypermobility, hypomobility, or restriction

- Shows normal or abnormal initiation of cervical motion

DMX uses digital and optic technology now available. DMX is the latest generation of videofluoroscopy (VF) that uses low doses of radiation. The images have improved clarity and resolution over VF and are recorded digitally on CD or DVD disc. DMX digital images can be replayed and studied on standard computer systems. DMX images are simply x-ray images taken at 30 frames per second to form a multiple radiographic array or series that can be run as a movie file to display real time motion of the joints of the body.

DMX radiographic series can be paused at any location and the measurements and interpretation common to radiology can be applied to the still images. These images would be identical to plain film images if plain film radiography were performed at the same location at the same moment in motion. DMX acquires approximately 2700 images for the same amount of radiation as seven regular x-rays.

For more information visit http://www.dmxofmontana.com

Myelogram

The myelogram is a special kind of x-ray test where a special dye is injected into the spinal sac. The dye shows up on an x-ray. It helps a doctor see if there is a herniated disc, pressure on the spinal cord or spinal nerves, or a spinal tumor. Before the CT scan and the MRI scan were developed, the myelogram was the only test that surgeons had to look for a herniated disc. The myelogram is still used today but not nearly as often. The myelogram is usually combined with CT scan to give more detail.

Bone Scan

A bone scan is a special test where radioactive tracers are injected into your blood stream. The tracers then show up on special x-rays of your neck. The tracers build up in areas where bone is undergoing a rapid repair process, such as a healing fracture or the area surrounding an infection or tumor. Usually the bone scan is used to locate the problem and other tests such as the CT scan or MRI scan are then used to look at the area in detail.

Electromyogram (EMG)

An electromyogram (EMG) is a special test used to determine if there are problems with any of the nerves going to the upper limbs. EMGs are usually done to see if one or more nerve roots have been pinched by a herniated disc. During the test, small needles are placed into certain muscles that are supplied by each nerve root. If there has been a change in the function of the nerve, the muscle will send off different types of electrical signals. The EMG test reads these signals and can help determine which nerve root is involved.

Grading the Severity of Injury

The physical exam combined with the imaging studies help determine the severity or grade of the injury. There is more than one way to assign a grade to a patient’s whiplash. Here are two examples of the more commonly used models used to classify or grade whiplash injuries:

Croft Guidelines

- Grade I: Minimal – No limitation of motion, no ligamentous injury, no neurological findings

- Grade II: Slight – Slight limitation of motion, no ligamentous injury, no neurologic findings

- Grade III: Moderate – Limitation of motion, ligamentous instability, neurologic symptoms present

- Grade IV: Moderate-to-Severe – Limitation of motion, some ligamentous injury, neurological symptoms, fracture or disc derangement

Quebec Whiplash Classification

- Grade 0: No complaint or physical sign

- Grade I: Neck complaint of pain, stiffness or tenderness, no physical signs

- Grade II: Neck pain and musculoskeletal signs

- Grade III: Neck pain and neurological signs

- Grade IV: Neck pain and fracture or dislocation

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Whenever possible, doctors prefer to use treatments other than surgery. The first goal of these nonsurgical treatments is to ease your pain and other symptoms.

Your health care providers will work with you to improve your neck movement and strength. They will also encourage healthy body alignment and posture. These steps are designed to enable you to get back to your normal activities. Conservative care may include:

- Immobilization

- Medication

- Injection

- Physical therapy

- Chiropractic care

Immobilization

At first, your doctor may prescribe immobilization of the neck. Keeping the neck still for a short time can calm inflammation and pain. This might include one to two days of bed rest and the use of a soft cervical (neck) collar.

The collar is a padded ring that wraps around the neck and is held in place by a Velcro strap. A soft cervical collar may be used for the first 24 to 48 hours to help provide support and reduce pain. There is no need for a hard or rigid cervical collar unless the neck is fractured.

Soft collars should not be worn after 48 hours without a physician’s approval. Studies show that prolonged immobilization can delay healing and promote disability. Wearing it longer tends to weaken the neck muscles and reduces the facet joints’ sense of position called proprioception.

A cervical support pillow may offer some additional support while sleeping and helps to keep the neck in a more neutral position. Cervical pillows can be used any time by anyone for improved alignment while sleeping.

Medication

Your doctor may prescribe certain types of medication if the nerves are irritated or compressed and you have neck pain that travels down your arm (radiculopathy). Severe symptoms may be treated with narcotic drugs, such as codeine or morphine. But these drugs should only be used for the first few days or weeks after problems with radiculopathy start because they are addictive when used too much or improperly. Muscle relaxants may be prescribed to calm neck muscles that are in spasm. You may be prescribed anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin or ibuprofen.

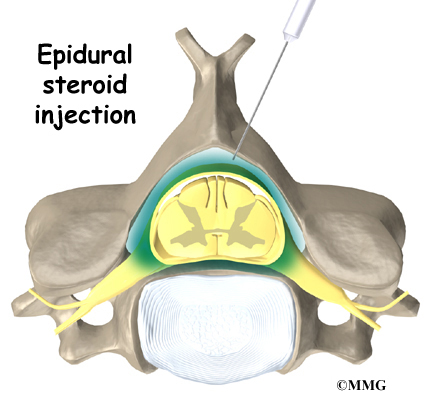

Injection

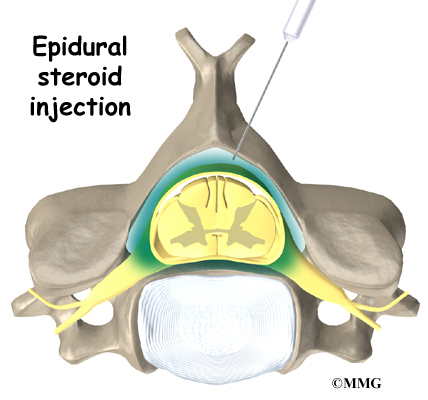

Pain resulting from irritation of the facet joints may be alleviated with injection of an anesthetic agent similar to Novacaine such as Bipuvacaine. This numbing agent both confirms the source of pain as coming from the joint and helps reduce or eliminate the pain.

Physical Therapy

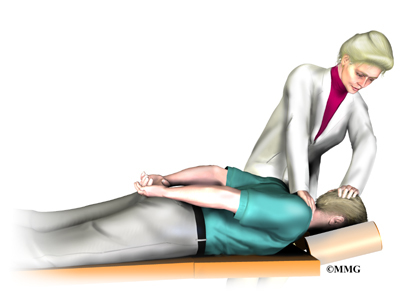

Some doctors have their patients work with a physical therapist. If you require outpatient physical therapy, you will probably only need to attend therapy sessions for two to four weeks. Your rate of recovery helps determine the length of time in physical therapy. Patients with delayed recovery may need longer time in rehab.

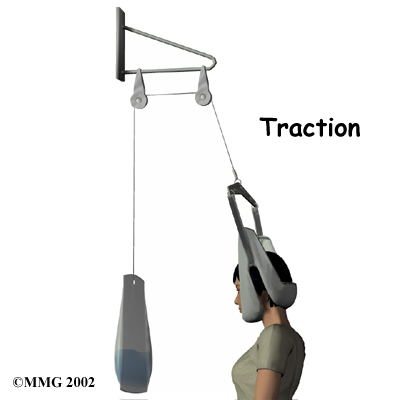

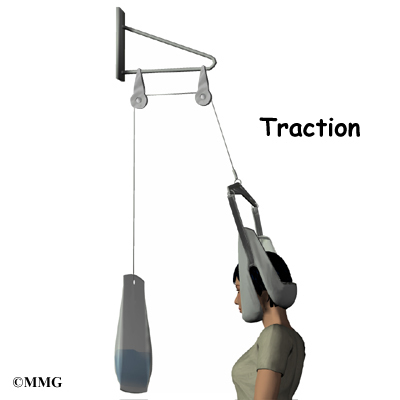

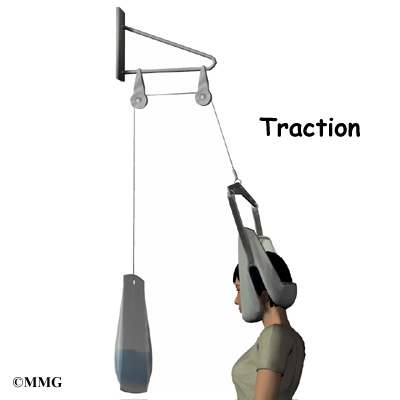

At first, treatment is focused on easing pain and reducing inflammation. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments are commonly used to help with these goals. Electrical stimulation treatments can help calm muscle spasm and pain. Traction is a way to gently stretch the joints and muscles of the neck. It can be done using a machine with a special head halter, or the therapist can apply the traction pull by hand. Your therapist may also use massage and other hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

Active treatments are added within the comfortable range of motion. The therapist will teach you specific exercises to help tone and control the muscles that stabilize the neck and upper back.

Your therapist will work with you on how to move and do activities. This form of treatment, called body mechanics, is used to help you develop new movement habits. This training helps you keep your neck in safe positions as you go about your work and daily activities. You’ll learn how to keep your neck safe while you lift and carry items and as you begin to do other heavier activities.

As your condition improves, your therapist will begin tailoring your program to help prepare you to go back to work. Some patients are not able to go back to a previous job that requires heavy and strenuous tasks. Your therapist may suggest changes in job tasks that enable you to go back to your previous job. Your therapist can also provide ideas for alternate forms of work. You’ll learn to do your tasks in ways that keep your neck safe and free of extra strain.

Chiropractic care

Chiropractic care also offers another opportunity for relief of pain from a whiplash injury. Chiropractors adjust misalignments of the facet joints and vertebrae to restore the nerve signals and improve spinal health, which can impact overall physical health. Many chiropractors make these adjustments using a thrust technique called manipulation.

Chiropractors also take into account how nutrition, emotion, and environment affect our health. The chiropractor will assess your posture during daily activities, work, and sleep and offer you suggestions for ways to improve your day-to-day spinal alignment. You may be given some additional advice about the use of heat, cold, and exercise to help maintain the results of your chiropractic treatment.

Surgery

Most people with lingering effects from whiplash or cervical radiculopathy from whiplash get better without surgery. In rare cases, surgery may be suggested.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect as I recover?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

You should expect full recovery to take up to three months. Integration of rehabilitation and manipulative therapy is central in getting back to your pre-injury status.

There is a strong emphasis on keeping as active as possible, which includes incorporating manual treatments and exercise. Before your rehab program ends, your healthcare team will teach you how to maintain any improvements you’ve made and ways to avoid future problems.

Cervical Artificial Disc Replacement

A Patient’s Guide to Cervical Artificial Disc Replacement

Introduction

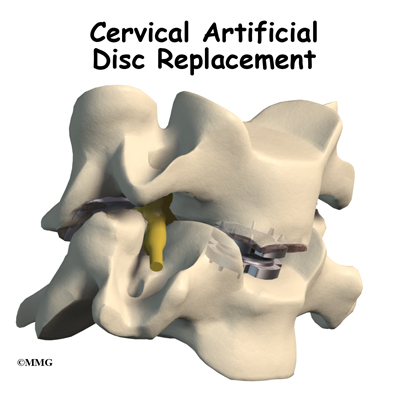

Artificial disc replacement (ADR) is relatively new. In June 2004, the first ADR for the lumbar spine (low back) was approved by the FDA for use in the US. Replacing a damaged disc in the cervical spine (neck) is a bit trickier. The disc is part of a complex joint in the spine. Making a replacement disc that works and that will last is not an easy task. There are now several Cervical artificial disc replacement devices that have been approved by the FDA for use in the United States.

The artificial disc is inserted in the space between two vertebrae. The goal is to replace the diseased or damaged disc while keeping your normal neck motion. The hope is that your spine will be protected from similar problems above and below the affected spinal level.

This guide will help you understand:

- what parts of the spine are involved

- what your surgeon hopes to achieve

- who can benefit from this procedure

- how do I prepare for surgery

- what happens during the procedure

- what to expect as you recover

Anatomy

What parts of the spine are involved?

Disc replacement typically occurs at cervical spine levels C4-5, C5-6, or C6-7. The first seven vertebrae make up the cervical spine. Doctors often refer to the cervical vertebrae as C1 to C7. The cervical spine starts where the top vertebra (C1) connects to the bottom of the skull. The cervical spine curves slightly inward and ends where C7 joins the top of the thoracic spine (the chest area) at the first thoracic vertebra, T1.

Each vertebra is made of the same parts. The main section of each cervical vertebrae, from C2 to C7,

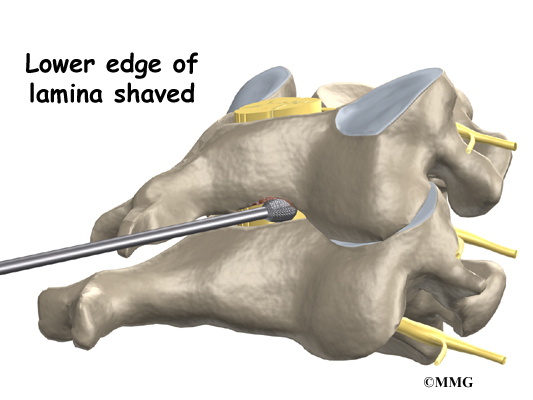

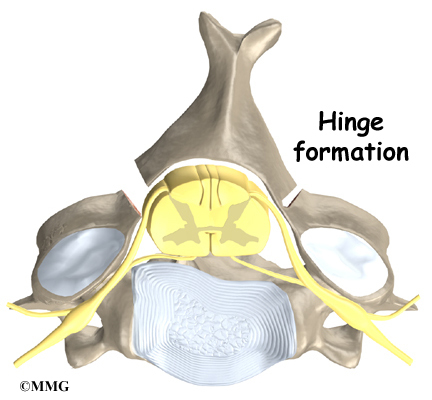

is formed by a round block of bone, called the vertebral body. A bony ring attaches to the back of the vertebral body. This ring has two parts. Two pedicles connect directly to the back of the vertebral body. Two lamina bones join the pedicles to complete the ring. The lamina bones form the outer rim of the bony ring. When the vertebrae are stacked on top of each other, the bony rings form a hollow tube that surrounds the spinal cord. The laminae provide a protective wall around the spinal cord.

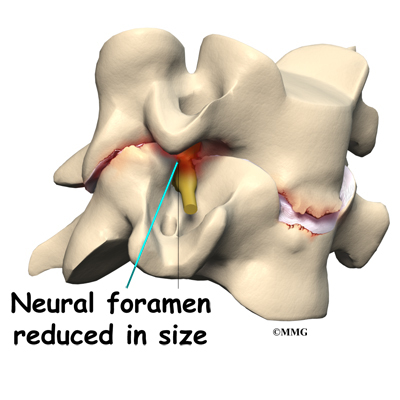

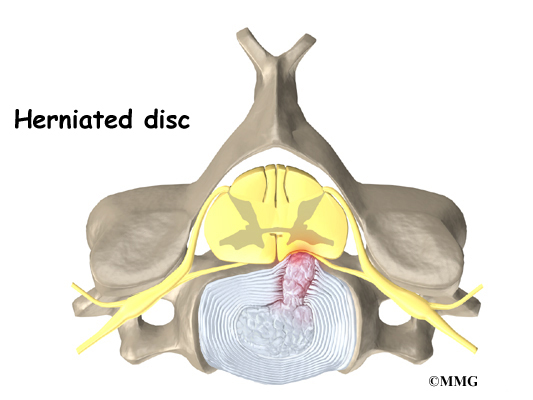

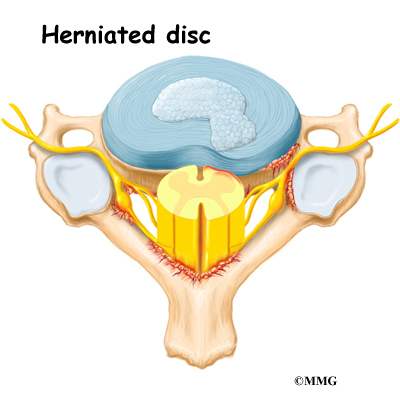

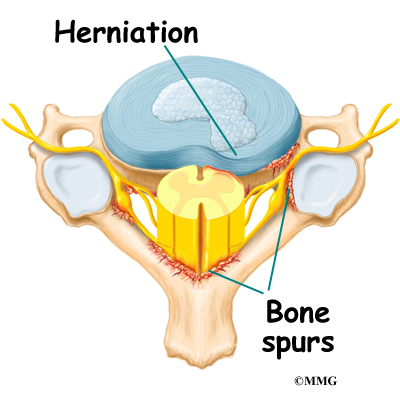

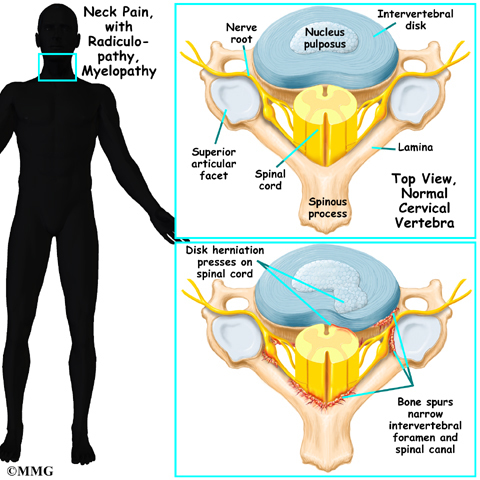

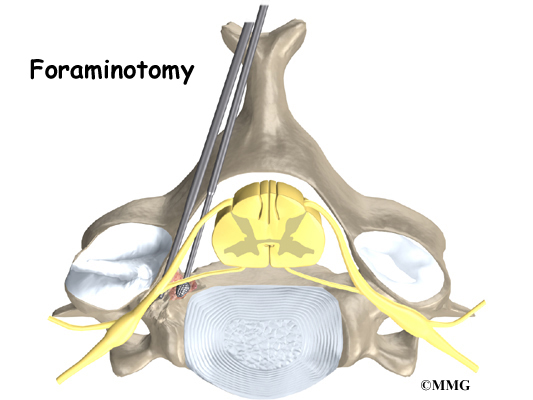

On the left and right side of each vertebra is a small tunnel called a neural foramen. (Foramina is the plural term.) The two nerves that leave the spine at each vertebra go through the foramina, one on the left and one on the right. The intervertebral disc sits directly in front of the opening. A bulged or herniated disc can narrow the opening and put pressure on the nerve. A facet joint sits behind the foramen. Bone spurs that form on the facet joint can project into the tunnel, narrowing the hole and pinching the nerve.

A special type of structure in the spine called an intervertebral disc has two parts. The center, called the nucleus, is spongy. It provides most of the shock absorption in the spine. The nucleus is held in place by the annulus, a series of strong ligament rings surrounding it.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Cervical Spine Anatomy

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to achieve?

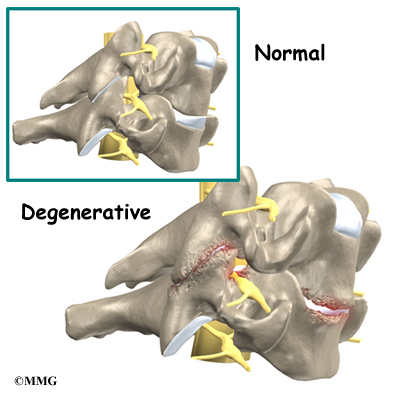

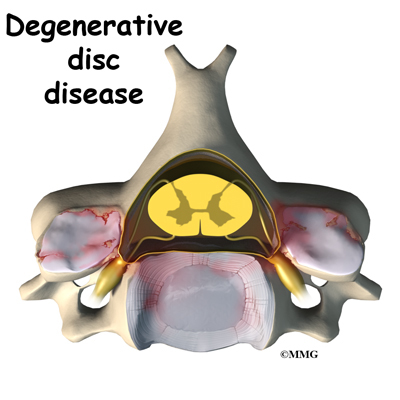

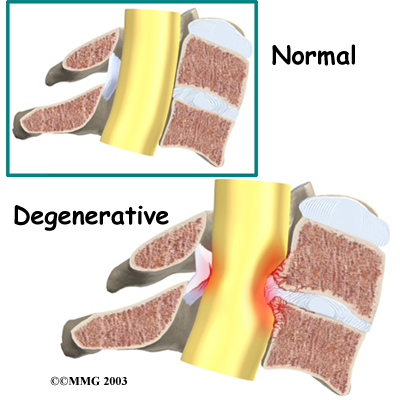

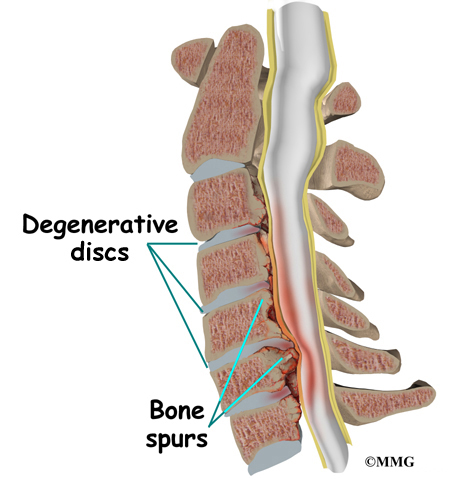

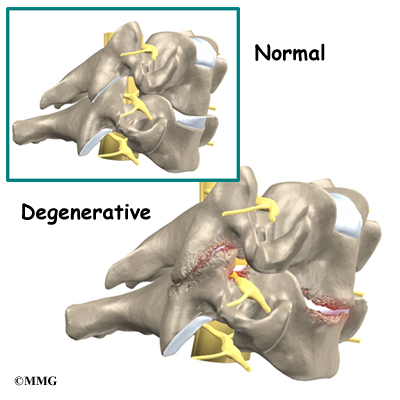

Disc replacement surgery is done to stop the symptoms of degenerative disc disease. Discs wear out or degenerate as a natural part of aging and from stress and strain on the neck. Eventually, the problem disc collapses. This causes the vertebra above to sink toward the one below. This loss of disc height affects the nearby structures – especially the facet joints.

When the disc collapses, it no longer supports its share of the load in the cervical spine. The facet joints of the spine begin to support more of the force that is transmitted between each vertebra. This increases the wear and tear on the articular cartilage that covers the surface of the joints. The articular cartilage is the smooth, slippery surface that covers the surface of the bone in any joint in the body. Articular cartilage is tough, but it does not tolerate abnormal pressure well for long. When damaged, articular cartilage does not have the ability to heal. This wear and tear is what is commonly referred to as arthritis.

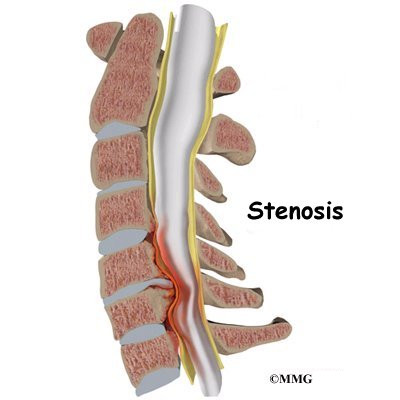

Shrinking disc height also reduces the size of the neural foramina, the openings between each vertebral pair where the nerve roots leave the spinal column. The arthritis also results in the development of bone spurs that may protrude into these openings, further narrowing the space that the nerves have to exit the spinal canal. The nerve roots can end up getting squeezed where they pass through the neural foramina.

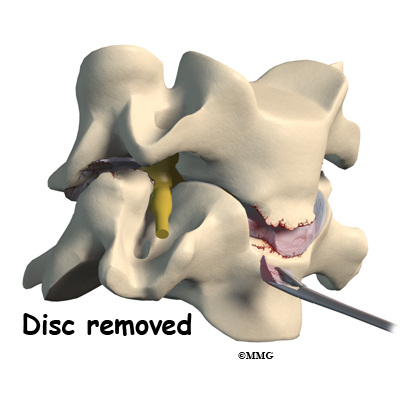

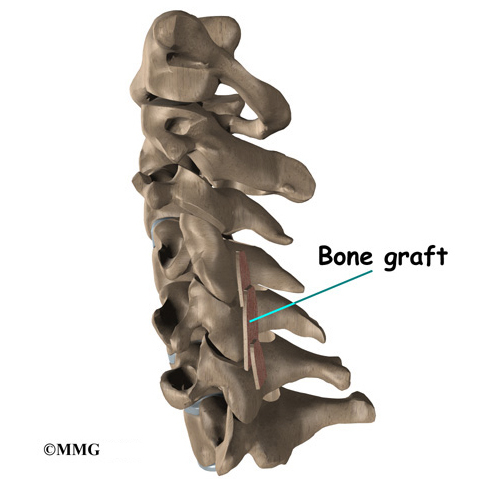

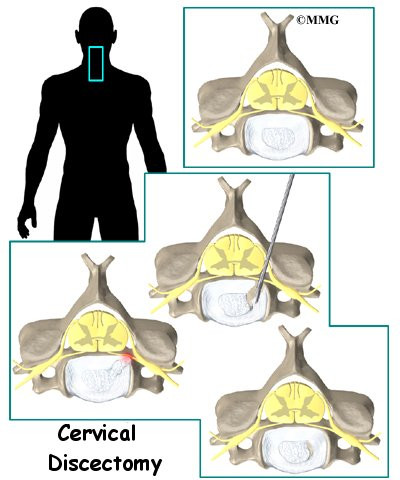

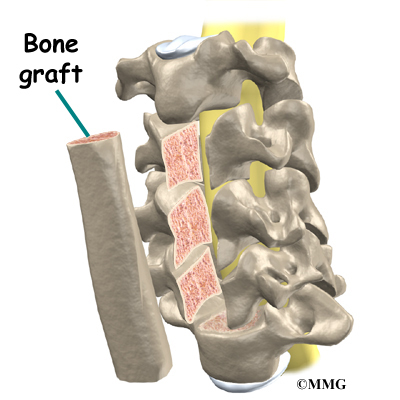

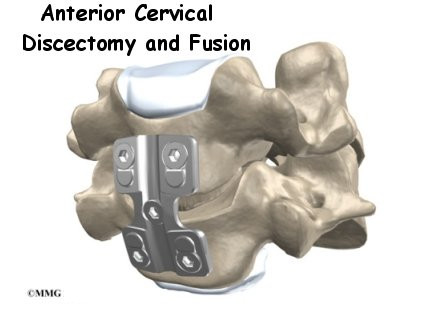

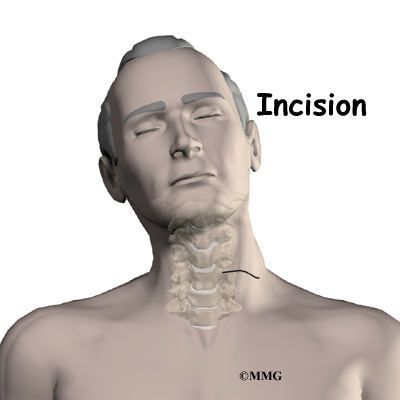

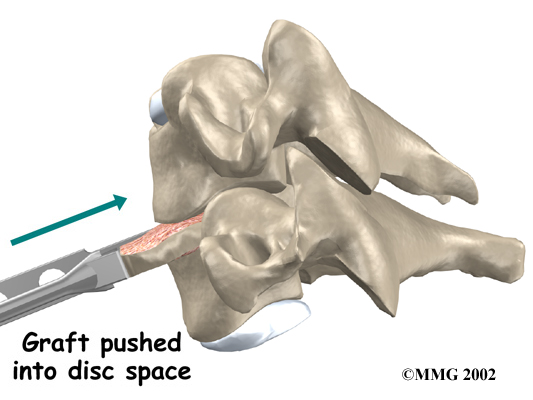

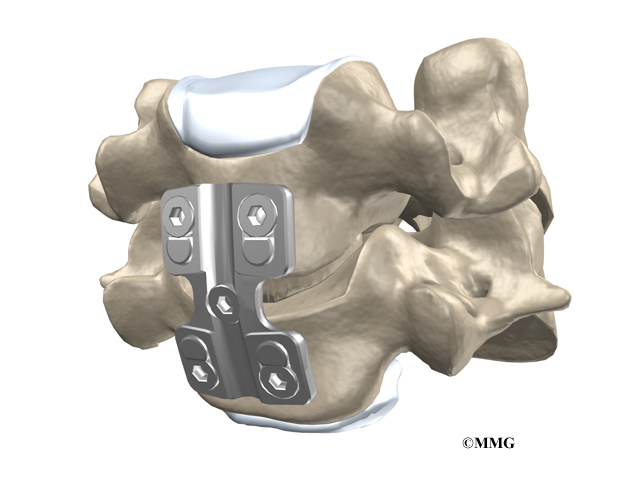

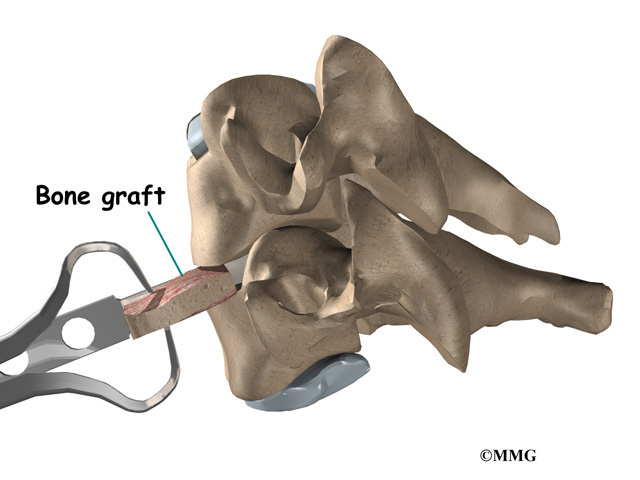

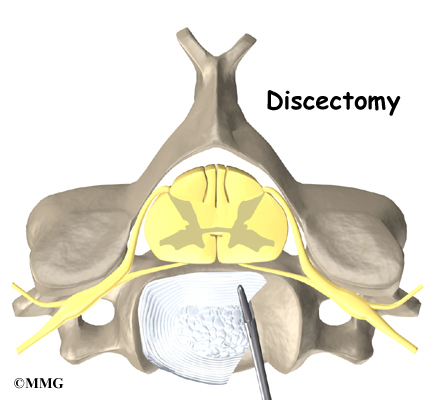

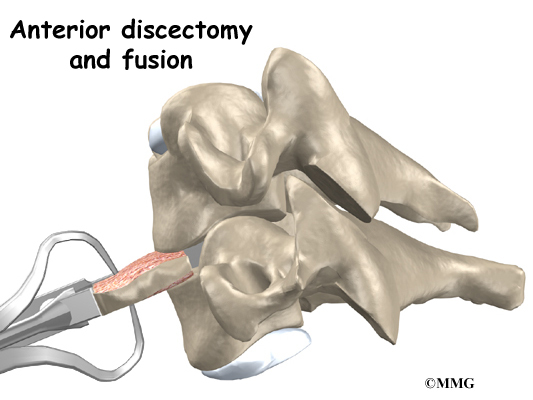

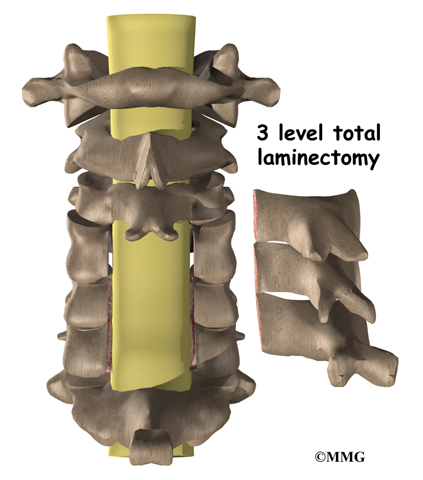

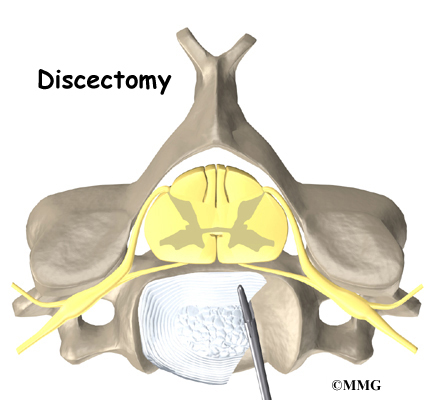

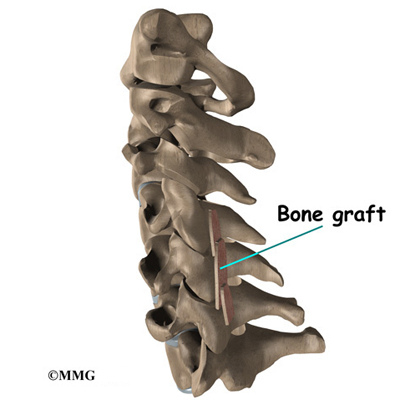

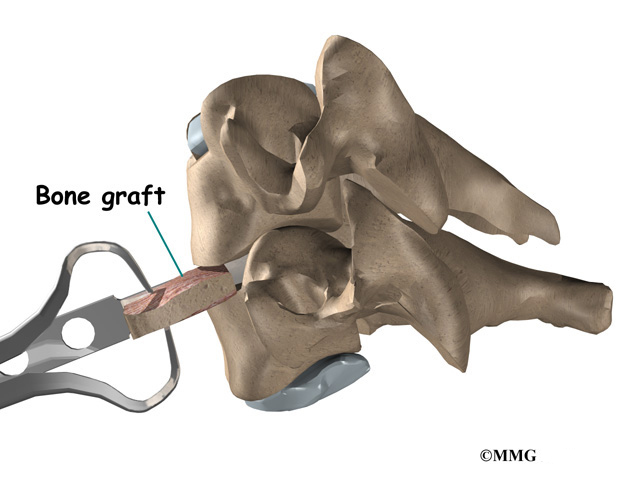

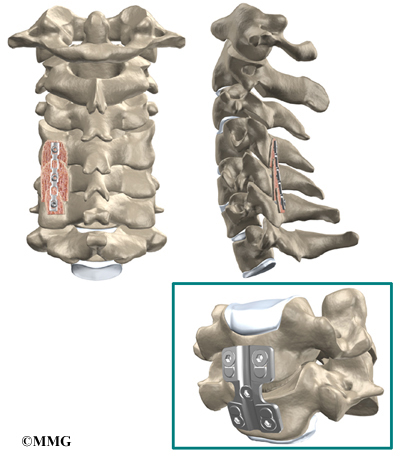

The traditional way of treating severe neck pain caused by disc degeneration is a procedure called an anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. In this procedure, the surgeon makes an incision in the anterior (front) of the neck, performs a discectomy (removes the disc) and fuses the two vertebrae together. A fusion simply means that two bones grow together. Usually, when two vertebrae are fused together, a small piece of bone called a bone graft is inserted between the two vertebrae where the disc has been removed. This bone graft serves to both separate the vertebrae and to stimulate the two bones to grow together – or fuse.

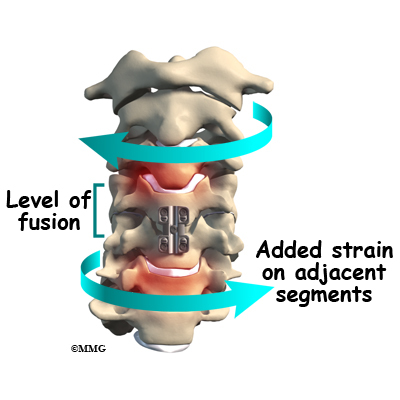

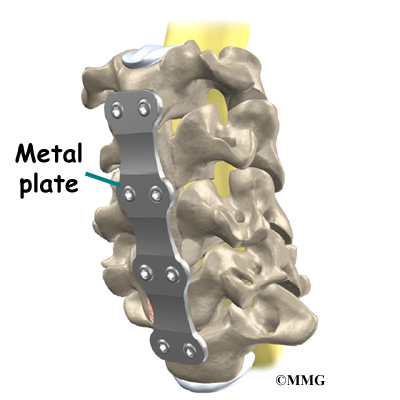

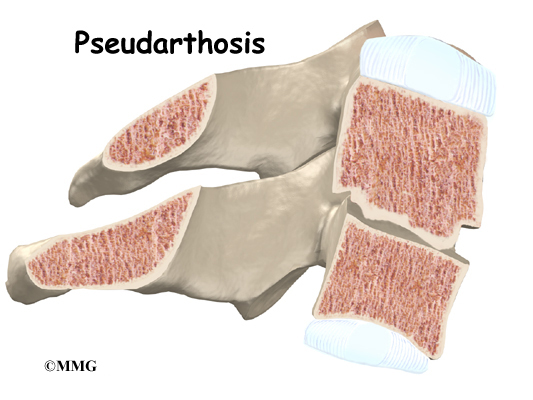

The fusion procedure usually involves the use of hardware, such as screws, plates, or cages to keep the bones from moving. Fusion restricts movement in the problem area, but it creates greater strain on the healthy spinal segments above and below. The added strain may eventually cause these segments to wear out. This is called adjacent-segment degeneration.

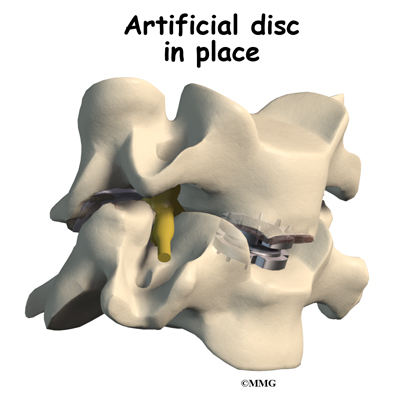

Replacing the damaged disc with an artificial disc, or implant, called a prosthesis can restore the normal distance between the two vertebrae. The artificial disc sits between the two vertebrae and “jacks up” the upper vertebra. Enlarging the disc space relieves pressure on the facet joints. It also opens up the space around the spinal nerve roots where they pass through the neural foramina.

Another benefit of the artificial disc replacement is that it mimics a healthy disc. Natural motion is preserved in the spine where the new disc is implanted. And it helps maintain stability in the spinal joints above and below it.

Who can benefit from this procedure

The indications for a cervical disc replacement are generally the same as for a cervical discectomy and fusion. A person must have symptoms from a cervical disc problem. Symptoms include neck and/or arm pain, arm weakness, or arm and hand numbness. These symptoms may be due to a herniated disc and/or bone spurs called osteophytes pressing on adjacent nerves or the spinal cord. This condition typically occurs at cervical spine levels C4-5, C5-6, or C6-7.

Artificial disc replacement is still somewhat new in the United States. In the United States, surgeons are currently only replacing one cervical disc in a patient’s cervical spine at this time. In Europe, surgeons are replacing more than one disc. More surgeons in the United States will probably start replacing more than one cervical disc in the near future.

Cervical artificial disc replacement is indicated for the treatment of radiculopathy (pressure on the spinal nerve) and myelopathy (pressure on the spinal cord) at one or two levels. In the future, it may be used for the treatment of three or more symptomatic levels or levels adjacent to a cervical spine fusion. This use is still under investigation.

More data is needed before the uses of cervical artificial disc replacements are expanded to other problems in the cervical spine. Cervical artificial disc replacement is not advised when there is cervical spine instability, significant facet joint damage, or infection.

Preparation

How should I prepare for surgery?

Your spine surgeon will gather a variety of information before recommending disc replacement surgery. In addition to taking a history and doing a physical exam, your surgeon may order various diagnostic studies, such as x-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, CT scans, or discograms.

Once you and your surgeon have agreed that disc replacement surgery is indicated, certain preparations for the surgery are important. Your doctor may tell you to be NPO for a certain amount of time before the procedure. This means that you should not eat or drink anything for a certain amount of time before your procedure. This means no water, no coffee, no tea – not anything. You may receive special instructions to take your usual medications with a small amount of water. Check with your doctor if you are unsure what to do.

You should tell your doctor if you are taking any medications that thin your blood or interfere with blood clotting. The most common blood thinner is Coumadin. Other medications also slow down blood clotting. Aspirin, ibuprofen, and nearly all of the anti-inflammatory medications affect blood clotting. So do medications used to prevent strokes such as Plavix. These medications usually need to be stopped seven days prior to the procedure. Be sure to let your doctor know if you are on any of these medications.

You should stop smoking or using tobacco in any form as soon as possible before surgery. This is very important to reduce complications from heart and lung problems. Tobacco use, especially smoking, also decreases the success rate of spine surgery. Stopping smoking will increase your chances of a successful result.

Discussions will be held with your family and people who may be assisting you once you return from the hospital. You may need to visit your primary care physician or internal medicine specialist to obtain medical clearance for surgery. This will ensure that you are in the best medical condition possible prior to the surgery.

Hospitals often have preoperative teaching for patients undergoing major spinal operations. These teaching sessions can help you understand what to expect both while you are in the hospital and after you return home. A doctor who will be performing your anesthesia (an anesthesiologist) will evaluate and counsel you regarding anesthesia.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during the operation?

Before we describe the procedure, let’s look first at the artificial disc itself.

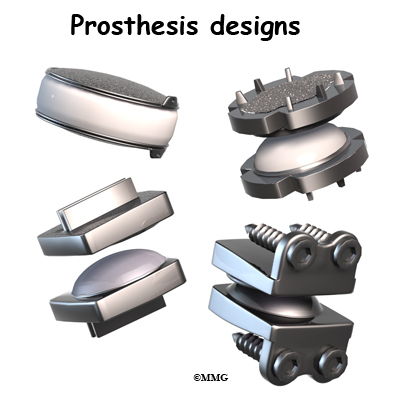

The cervical artificial disc has several different designs. Some look like a sandwich with two endplates separated by a plastic spacer. The two endplates are made of cobalt chromium alloy, a safe material that has been used for many years in replacement joints for the hip and knee.

A plastic (polyethylene) core fits in between the two metal endplates. The core acts as a spacer and is shaped so that the endplates pivot in a way that imitates normal motion of the two vertebrae. There are small prongs on one side of each endplate. The prongs help anchor the endplate to the surface of the vertebral body.

Another artificial disc replacement design is a ball and socket articulation to allow for normal translation of motion at that segment. The implant may be made of titanium and polyurethane in a metal-on-plastic design. Some are made of stainless steel and are all metal-on-metal.

Inserted between two vertebrae, the prosthesis reestablishes the height between two vertebrae. As a result of enlarging the disc space, the nearby spinal ligaments are pulled tight, which helps hold the prosthesis in place. The prosthesis is further held in place by the normal pressure through the spine.

The Operation

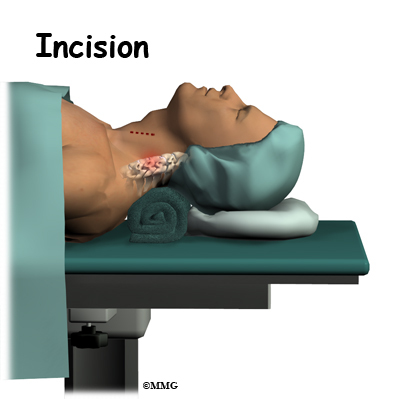

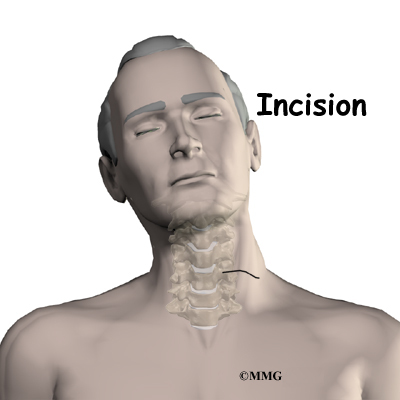

The operation is done from the anterior (front) of the body. This surgical approach is the same as that presently used for a discectomy and fusion operation. To do this, the patient is placed on his or her back. An incision is made through the skin and the thin muscles of the front of the neck. The blood vessels, the trachea (windpipe), and the esophagus are moved to the side so that the surgeon can see the front of the cervical spine. The disc that is to be replaced is identified using the fluoroscope. The fluoroscope is an x-ray machine that allows the doctor to actually see an x-ray image while doing the procedure.

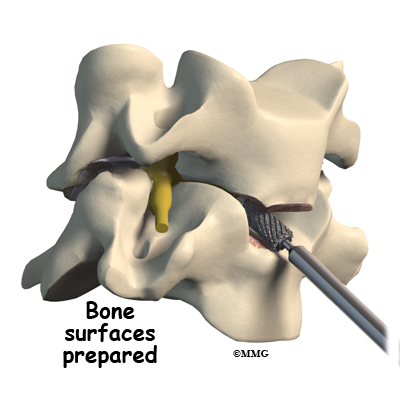

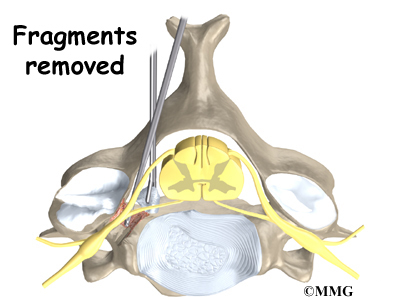

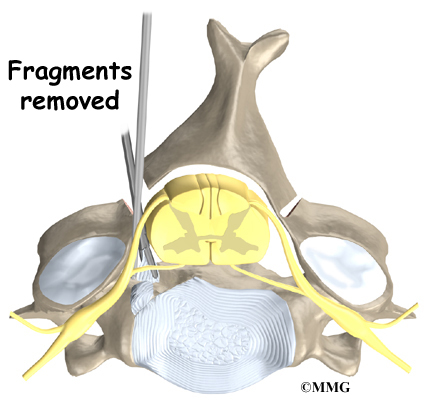

Working from the front of the spine, the spine surgeon removes a large section from the middle of the damaged disc. Next, the bones of the spine are spread apart to make more room to see and work inside the disc space. Using a surgical microscope, any remaining disc material toward the back of the disc is removed. The surgeon will also remove any disc fragments pressing against the nerve and shave off any osteophytes (bone spurs).

The disc space is distracted (jacked up) to its normal disc height. This step helps decompress or take pressure off the nerves. At this point, x-rays or a fluoroscope, is used to insert the artificial disc device into the prepared disc space. This allows the doctor to watch where the implant goes as it is inserted. This makes the procedure much safer and much more accurate.

Finally, the prosthesis is tested by moving the spine in various positions. An X-ray may be taken to double check the location and fit of the new disc.

View animation of artificial disc replacement

Complications

What might go wrong?

All types of spine surgery, including artificial disc replacement, have certain risks and benefits. Weigh these as you gather advice and information. Be sure to discuss the possible risks of disc replacement with your spine surgeon.

Medical complications arising from spinal surgery are rare but could include stroke, heart attack, spinal cord or spinal nerve injury, pneumonia, or possibly death.

However, information from the disc replacement operations shows a low rate of complications. There have been no reports of death, significant infection, or major neurological problems.

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications are

- anesthesia complications

- thrombophlebitis

- infection

- blood loss

- nerve injury or paralysis

- spontaneous ankylosis (fusion)

- subsidence (sinking)

- implant failure (need for further surgery)

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

View animation of pulmonary embolism

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when blood clots form in the large veins of the leg. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible after surgery. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Infection following spine surgery is rare but can be a very serious complication. Some infections may show up early, even before you leave the hospital. Infections on the skin’s surface usually go away with antibiotics. Deeper infections that spread into the bones and soft tissues of the spine are harder to treat and may require additional surgery to treat the infected portion of the spine.

Blood Loss

Cervical disc replacement surgery carries risks associated with operating from the front of the spine. Blood vessels that travel near the front of the spine may be injured during anterior cervical surgery.

Nerve Injury

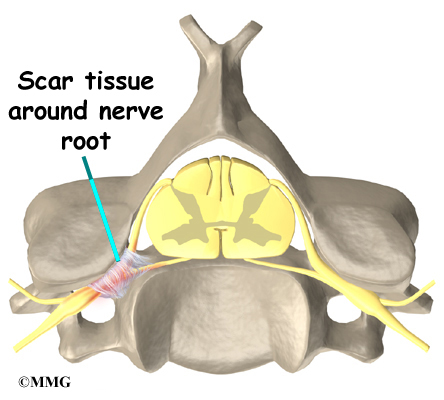

Any surgery that is done near the spinal canal can potentially cause injury to the spinal cord or spinal nerves. Injury can occur from bumping or cutting the nerve tissue with a surgical instrument, from swelling around the nerve, or from the formation of scar tissue. An injury to these structures can cause muscle weakness and a loss of sensation to the areas supplied by the nerve.

The nerve to the voice box is sometimes injured during surgery on the front of the neck. When doing anterior neck surgery, surgeons prefer to go through the left side of the neck where the path of the nerve to the voice box is more predictable than on the right side. During surgery, the nerve may get stretched too far when retractors are used to hold the muscles and soft tissues apart. When this happens, patients may be hoarse for a few days or weeks after surgery. In rare cases where the nerve is actually cut, patients may end up with ongoing minor problems of hoarseness, voice fatigue, or difficulty making high tones.

Spontaneous Ankylosis (fusion)

Some things can go wrong with any implant. In the case of artificial disc replacements for the cervical spine, sometimes the spine fuses itself, a process called spontaneous ankylosis. Loss of neck motion is the main side effect of this problem.

Bone may also form in the soft tissues around the vertebrae. For example, cartilage turns to bone or bone-like tissue. This process is called ossification. Ossification may not affect the implant or your final results in terms of motion or function.

Some patients are left with pain, numbness, and weakness. This can occur when there’s been incomplete neurologic decompression. In other words, there is still pressure on the spinal cord or spinal nerves.

Subsidence (sinking)

Subsidence is another possible problem. The implant actually sinks down into the vertebral body above or below it. This results in a loss of the normal disc height. Neurologic compression with neurologic symptoms can occur.

Implant Failure (need for further surgery)

Over time, wear and tear just from the physical process of motion across a bearing surface can cause tiny bits of debris to flake off the implant. The body may react to these particles with an inflammatory response that can cause pain, implant loosening, and implant failure. So far, significant inflammatory reactions have not been reported for spinal artificial disc replacements. In rare cases, the artificial disc replacement can dislocate.

After Surgery

What happens after surgery

Most people spend one or two days in the hospital. You may require an extra day or two if for some reason you’re having extra pain or unexpected difficulty. Patients generally recover quickly after the artificial disc procedure.

You should be able to get out of bed and walk within a few hours. Move carefully and comfortably, and avoid extending your neck (bending backward). You may need to wear a brace or soft collar for a short while after the operation to support your neck muscles.

As you recover in the hospital, a physical therapist may see you one or two times each day until you go home. You’ll be shown ways to move, dress, and do activities without putting extra strain on your neck. Your therapist will help you begin a walking program in the hospital. You are encouraged to continue the walking program when you return home.

When you leave the hospital, there are very few activity restrictions. You should be safe to sit, walk, and drive. However, you should avoid lifting items for at least four weeks. Your surgeon will probably release you to return to work in two to four weeks. If your job requires moving and lifting heavy items, you may require a longer period of recovery. Your surgeon may give you the okay to do all your activities by the sixth week after surgery.

If you spend large amounts of time in front of a computer or other machine, you may need to change the height and angle of your work surface and/or the computer. Finding a position that puts minimal stress on your neck is important. You should avoid spending hours in one position reading, sewing, or doing other handwork. The therapist can help you find optimal positions and advise you about ways to stretch your neck muscles.

Rehabilitation

What should my recovery be like?

Your surgeon may prescribe outpatient physical therapy within one to two weeks after surgery. Plan on attending therapy two to three times each week for four to six weeks.

The first few visits include treatments to calm soreness and pain from the operation. Your therapist may apply gentle soft-tissue treatments such as massage. Ice and electrical stimulation are also commonly used to calm muscle spasm and to help take away any lasting pain.

Your therapist will teach you how to protect your neck. You’ll learn ways to position your neck when you sleep, sit, and drive. And you’ll be shown ways to keep your neck safe during routine activities, such as getting in or out of bed, getting dressed, and washing your hair.

Many patients are afraid to move the head and neck for fear of damaging or dislodging the disc. Using normal motion for everyday activities will not harm your new disc in any way. Your therapist will help you learn how to move your neck and show you any limits necessary.

Active treatments are used to improve flexibility, strength, and endurance. Gentle stretching exercises for the neck are commonly prescribed. You’ll begin a series of strengthening exercises to help tone and control the muscles that stabilize the neck and upper back. It is also important to build strength in your arms. Endurance exercises may include treadmill walking, swimming, or stationary biking.

When your symptoms are under control and you’re comfortable doing your exercises, your formal therapy sessions will end. You’ll continue your exercises as part of a home program.

Summary

Artificial disc replacement offers an alternative to cervical fusion for some patients who have chronic neck pain from degenerative disc disease. While fusion stops pain by eliminating movement in the problem spinal segment, ADR allows natural motion in the part of the spine where the disc is implanted. This is because the prosthesis is designed to imitate normal movement between adjacent vertebrae.

A successful result means that your painful symptoms are better but not necessarily perfect. You can expect to have significantly less neck pain and greatly improved function with the operation. You can expect to discontinue the use of strong medications.

But remember, no one can guarantee that you’ll be free of pain or that your spine will be totally flexible after this type of surgery. The idea that preserving motion will decrease adjacent segment degeneration hasn’t been proven yet. Long-term results (10 or more years) are unavailable.

Posterior Cervical Fusion

A Patient’s Guide to Posterior Cervical Fusion

Introduction

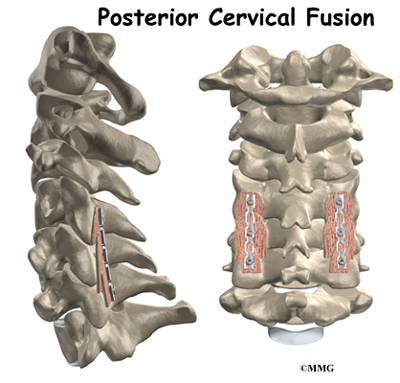

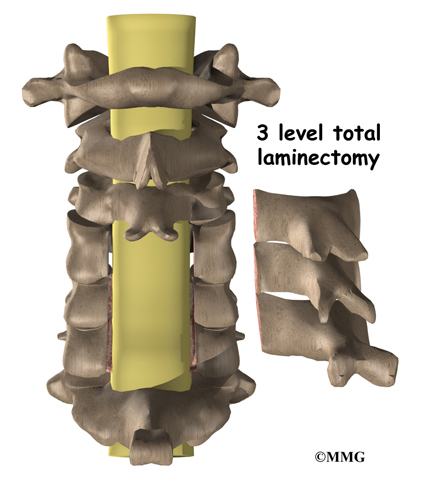

Posterior cervical fusion is done through the back (posterior) of the neck. The surgery joins two or more neck vertebrae into one solid section of bone. The medical term for fusion is arthrodesis. Posterior cervical fusion is most commonly used to treat neck fractures and dislocations and to fix deformities in the curve of the neck.

Surgeons sometimes attach metal hardware to the neck bones during posterior fusion surgery. This hardware is called instrumentation.

This guide will help you understand

- why the procedure becomes necessary

- what surgeons hope to achieve

- what to expect during your recovery

Anatomy

What parts of the neck are involved?

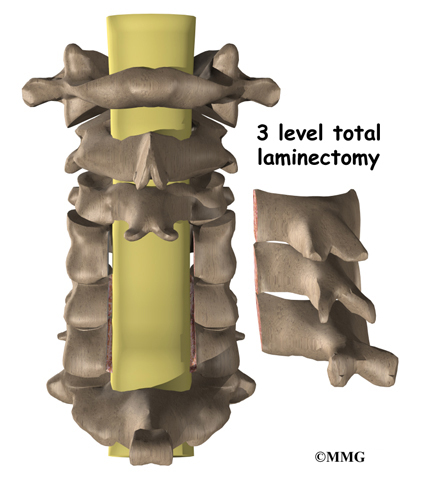

Surgeons do this surgery through the back part of the neck. The muscles on the back of the neck cover the bony ring around the spinal cord. The bony ring, formed by the pedicle and lamina bones, is called the spinal canal. The spinal canal is a hollow tube that surrounds the spinal cord as it passes through the spine.

The lamina acts like a protective roof over the back of the spinal cord. Facet joints line up on both sides along the back of the spinal column.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Cervical Spine Anatomy

Rationale

What do surgeons hope to achieve?

Posterior cervical fusion is used to stop movement between the bones of the neck. A serious fracture or dislocation of the neck vertebrae poses a risk to the spinal cord. The spinal cord is sometimes damaged by the fractured or dislocated bones. Surgeons hope to protect the spinal cord from additional injury by fusing these bones together.

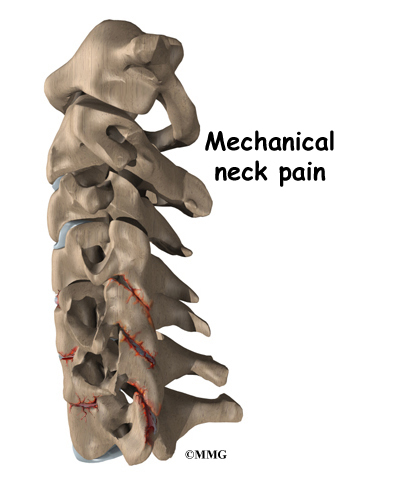

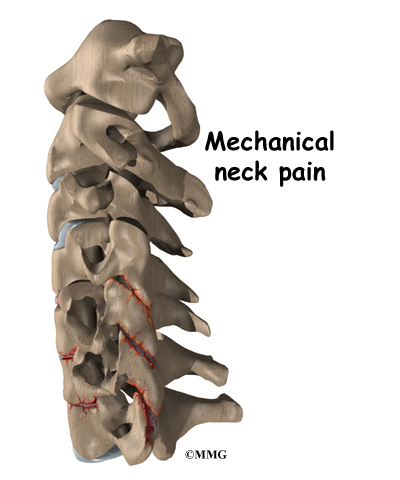

Surgeons also use posterior cervical fusion to help patients who have mechanical neck pain. Extra movement within the parts of the cervical spine can be a source of this type of neck pain. Fusing these bones together prevents the extra movement, easing pain.

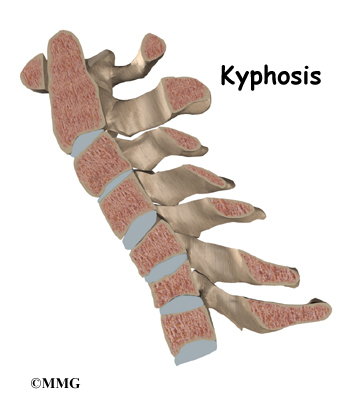

Posterior fusion is also used to line up and hold the neck bones when there’s a deformity in the curve of the neck. Normally, the neck lines up with a slight inward curve from the base of the skull to the top of the thorax (the chest area). One type of deformity that changes the curve of the neck is called kyphosis.

This happens when the inward curve starts to bow outward. Some people are born with an outward bow in their neck. Kyphosis can also occur when a severe injury compresses the vertebral body into the shape of a wedge. Neck surgeries that weaken the bony ring around the spinal canal can also lead to kyphosis. When kyphosis is a problem, a posterior fusion procedure may be used to correct the curve and to fuse the bones together once they’re in the right position.

Preparations

How will I prepare for surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery must be made jointly by you and your surgeon. You should understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during the operation?

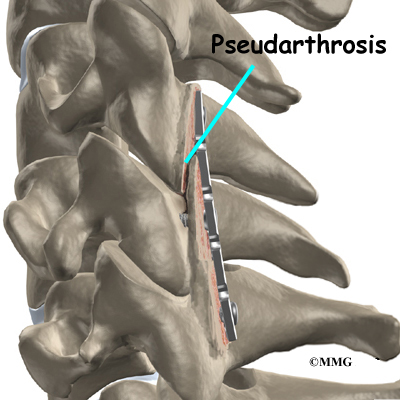

Patients are given a general anesthesia to put them to sleep during most spine surgeries. As you sleep, your breathing may be assisted with a ventilator. A ventilator is a device that controls and monitors the flow of air to the lungs.