A Patient’s Guide to Rotator Cuff Tears

Introduction

The shoulder is an elegant and complex piece of machinery. Its design allows us to reach and use our hands in many different positions. However, while the shoulder joint has great range of motion, it is not very stable. This makes the shoulder vulnerable to problems if any of its parts aren’t in good working order.

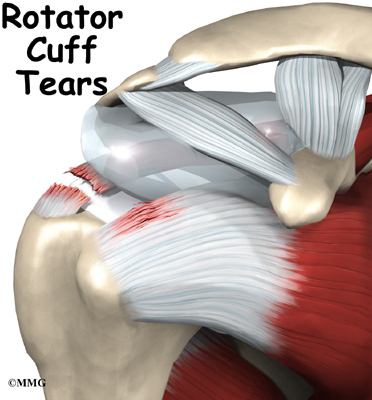

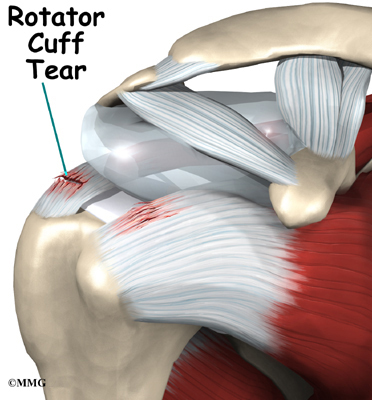

The rotator cuff tendons are key to the healthy functioning of the shoulder. They are subject to a lot of wear and tear, or degeneration, as we use our arms. Tearing of the rotator cuff tendons is an especially painful injury. A torn rotator cuff creates a very weak shoulder. Most of the time patients with torn rotator cuffs are in late middle age. But rotator cuffs tears can happen at any age.

This guide will help you understand

- what the rotator cuff is

- how it can become torn

- what treatments are available for a torn rotator cuff

Anatomy

What is the rotator cuff, and what does it do?

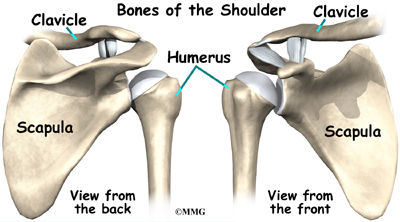

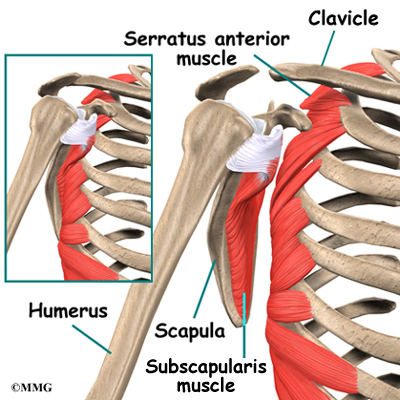

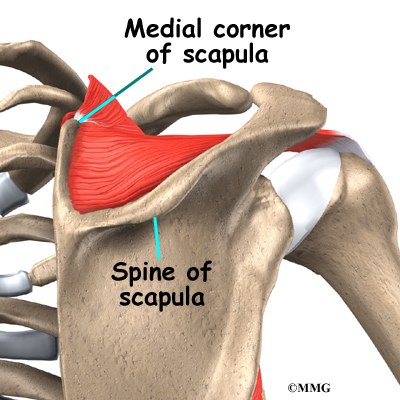

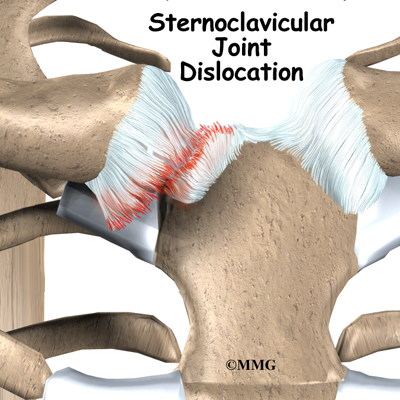

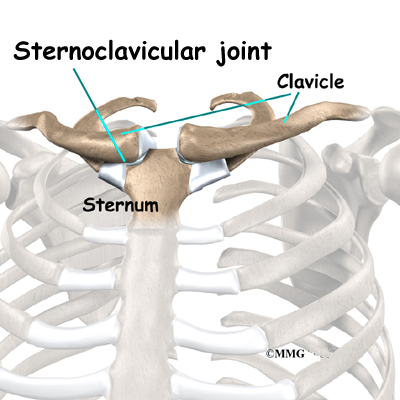

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone).

The rotator cuff connects the humerus to the scapula.

The rotator cuff is formed by the tendons of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

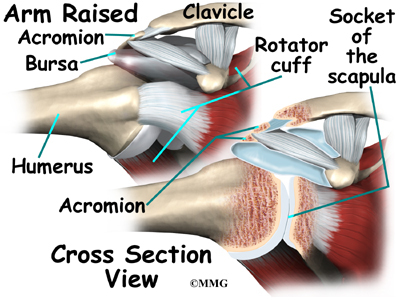

Tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move the bones by pulling on the tendons. The rotator cuff helps raise and rotate the arm.

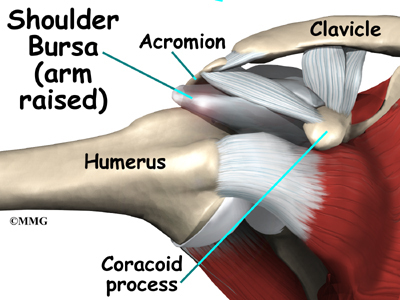

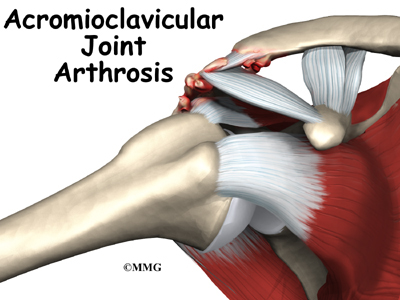

As the arm is raised, the rotator cuff also keeps the humerus tightly in the socket of the scapula. The upper part of the scapula that makes up the roof of the shoulder is called the acromion.

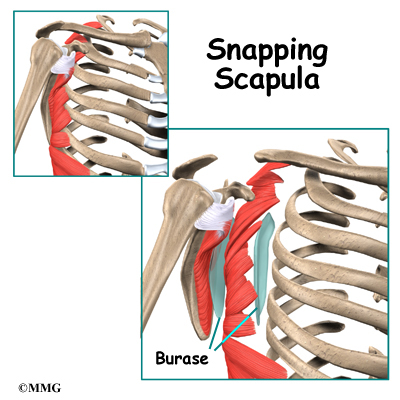

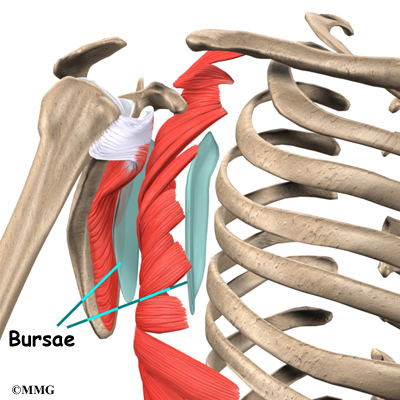

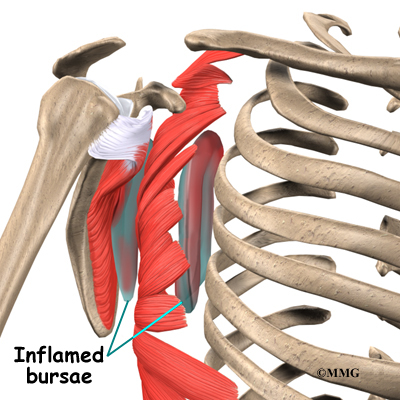

A bursa is located between the acromion and the rotator cuff tendons. A bursa is a lubricated sac of tissue that cuts down on the friction between two moving parts. Bursae are located all over the body where tissues must rub against each other.

In this case, the bursa protects the acromion and the rotator cuff from grinding against each other.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Causes

What causes the rotator cuff to tear?

The rotator cuff tendons have areas of very low blood supply. The more blood supply a tissue has, the better and faster it can repair and maintain itself. The areas of poor blood supply in the rotator cuff make these tendons especially vulnerable to degeneration from aging.

The degeneration of aging helps explain why the rotator cuff tear is such a common injury later in life. Rotator cuff tears usually occur in areas of the tendon that had low blood supply to begin with and then were further weakened by degeneration.

This problem of degeneration may be accelerated by repeating the same types of shoulder motions. This can happen with overhand athletes, such as baseball pitchers. But even doing routine chores like cleaning windows, washing and waxing cars, or painting can cause the rotator cuff to fatigue from overuse.

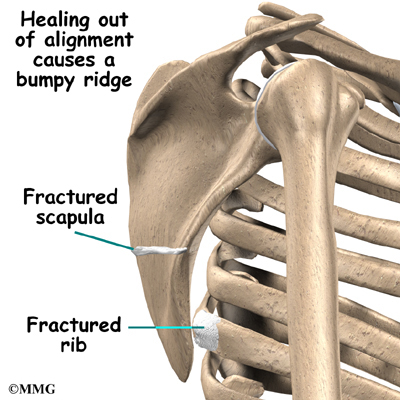

Excessive force can tear weak rotator cuff tendons. This force can come from trying to catch a heavy falling object or lifting an extremely heavy object with the arm extended. The force can also be from a fall directly onto the shoulder. Sometimes injuries that tear the rotator cuff are painful, but sometimes they aren’t. Researchers estimate that up to 40 percent of people may have a mild rotator cuff tear without even knowing it.

The typical patient with a rotator cuff tear is in late middle age and has had problems with the shoulder for some time. This patient then lifts a load or suffers an injury that tears the tendon. After the injury, the patient is unable to raise the arm. However, these injuries also occur in young people. Overuse or injury at any age can cause rotator cuff tears.

Symptoms

What does a rotator cuff tear feel like?

Rotator cuff tears cause pain and weakness in the affected shoulder. In some cases, a rotator cuff may tear only partially. The shoulder may be painful, but you can still move the arm in a normal range of motion. In general, the larger the tear, the more weakness it causes.

In other cases, the rotator cuff tendons completely rupture. A complete tear makes it impossible to move the arm in a normal range of motion. It is usually impossible to raise the arm away from your side by yourself.

Most rotator cuff tears cause a vague pain in the shoulder area. They may also cause a catching sensation when you move your arm. Most people say they can’t sleep on the affected side due to the pain.

Diagnosis

What tests will my doctor run?

Your doctor will ask questions about your medical history, your injury, and your pain. Your doctor will then do a physical examination of the shoulder. The physical exam is most helpful in diagnosing a rotator cuff tear. A complete tear is usually very obvious. If your doctor can move the arm in a normal range of motion, but you can’t move the arm yourself, you most likely have a torn rotator cuff.

X-rays won’t show tears in the rotator cuff. However, your doctor may want you to have a shoulder X-ray to see if there are bone spurs, a loss of joint space in the shoulder, or a down-sloping (hooked) acromion. These findings are associated with tears in the rotator cuff. An X-ray can also show if there are calcium deposits in the tendon that are causing your symptoms, a condition called calcific tendonitis.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Calcific Tendonitis

Your doctor will probably also want to do an arthrogram test. An arthrogram involves injecting dye into the shoulder joint and taking several X-rays. If the dye leaks out of the shoulder joint, there is probably a tear in the rotator cuff.

Your doctor may ask you to have a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan.

An MRI scan is a special imaging test that uses magnetic waves to create pictures of the shoulder in slices. The MRI scan shows tendons as well as bones. This test is painless and requires no needles or injections.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Your doctor’s first goal will be to help control your pain and inflammation. Initial treatment is usually rest and anti-inflammatory medication, such as aspirin or ibuprofen. This medicine is used mainly to control pain. Your doctor may suggest a cortisone injection if you have trouble getting your pain under control. Cortisone is a very effective anti-inflammatory medication.

Your doctor will probably have a physical or occupational therapist direct your rehabilitation program. At first, treatments such as heat and ice focus on easing pain and inflammation. Hands-on treatments and various types of exercises are used to improve the range of motion in your shoulder and the nearby joints and muscles.

Later, you will do strengthening exercises to improve the strength and control of the rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles. Your therapist will help you retrain these muscles to keep the ball of the humerus in the socket. This will help your shoulder move smoothly during all of your activities.

You may need therapy treatments for six to eight weeks. Most patients are able to get back to their activities with full use of their arm within this amount of time.

Surgery

A complete rotator cuff tear will not heal. Complete ruptures usually require surgery if your goal is to return your shoulder to optimal function. The exception is in elderly patients or patients who have other diseases that increase the risks of surgery. There is some evidence that repairing the rotator cuff within three months of the injury results in a better outcome. You will need to work with your surgeon to determine when is the best time to do the surgery.

Certain types of partial rotator cuff tears may not require surgical repair. If you have a partial tear, your surgeon will most likely want to further evaluate the situation and determine how much the tendon is torn and where the tendon is damaged. This information will be used to decide whether surgery should be recommended or whether you may want to consider non-surgical care for the partial tear of the tendon.

Today, the MRI scan is the most common test used to evaluate the shoulder and determine whether surgery is necessary. Your surgeon will be looking for details of your rotator cuff tear and checking for other problems. As mentioned earlier, a tear usually doesn’t occur unless the rotator cuff is already weakened by some other problem. Other potential problems include acromioclavicular (AC) joint osteoarthritis and impingement syndrome. Your surgery may need to address these conditions as well.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Osteoarthritis of the Acromioclavicular Joint

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Impingement Syndrome

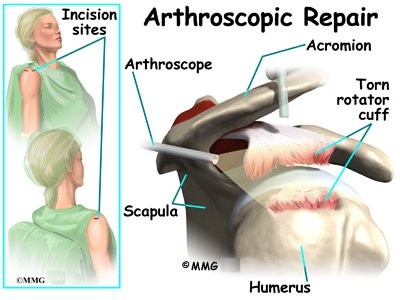

Arthroscopic Repair

In the past,

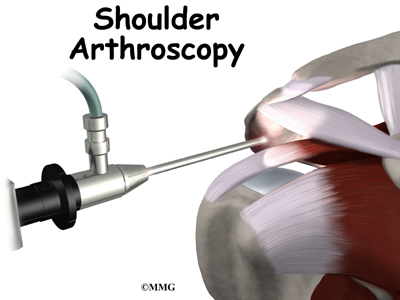

repair of the rotator cuff tendons usually required an open incisionthree or four inches in length. As surgeons have become more comfortable using the arthroscope to work in and around the shoulder joint, things have changed. Today, it is much more common to repair tears of the rotator cuff using the arthroscope.

An arthroscope is a special type instrument designed to look into a joint, or other space, inside the body. The arthroscope itself is a slender metal tube smaller than a pencil. Inside the metal tube are special strands of glass called fiberoptics. These small strands of glass form a lens that allows one to look into the tube on one end and see what is on the other side – inside the space. This is similar to a microscope or telescope. In the early days of arthroscopy, the surgeon actually looked into one end of the tube. Today, the arthroscope is attached to a small TV camera. The surgeon can watch the TV screen while the arthroscope is moved around in the joint. Using the ability to see inside the joint, the surgeon can then place other instruments into the joint and perform surgery while watching what is happening on the TV screen.

The arthroscope lets the surgeon work in the joint through a very small incision. This may result in less damage to the normal tissues surrounding the joint, leading to faster healing and recovery. If your surgery is done with the arthroscope, you may be able to go home the same day.

To perform the rotator cuff repair using the arthroscope, several small incisions are made to insert the arthroscope and special instruments needed to complete the procedure. These incisions are small, usually about one-quarter inch long. It may be necessary to make three or four incisions around the shoulder to allow the arthroscope to be moved to different locations to see different areas of the shoulder.

A small plastic, or metal, tube is inserted into the shoulder and connected with sterile plastic tubing to a special pump. Another small tube allows the fluid to be removed from the joint. This pump continuously fills the shoulder joint with sterile saline (salt water) fluid. This constant flow of fluid through the joint inflates the joint and washes any blood and debris from the joint as the surgery is performed.

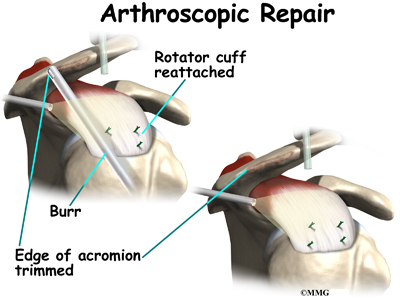

There are many small instruments that have been specially designed to perform surgery in the joint. Some of these instruments are used to remove torn and degenerative tissue. Some of these instruments nibble away bits of tissue and then vacuum them up from out of the joint. Others are designed to burr away bone tissue and vacuum it out of the joint. These instruments are used to remove any bone spurs that are rubbing on the tendons of the shoulder and smooth the under surface of the acromion and AC joint.

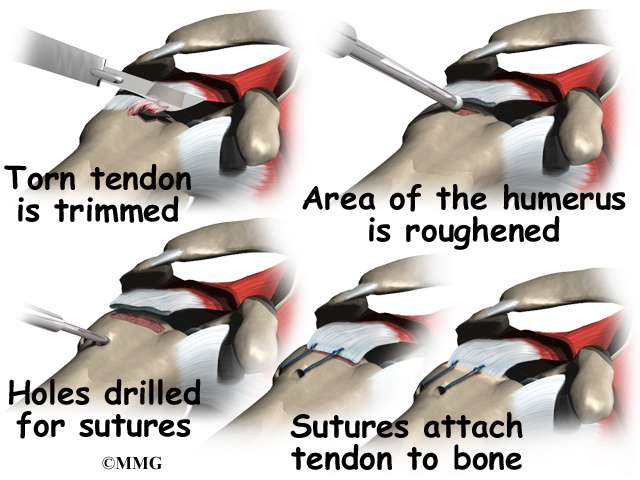

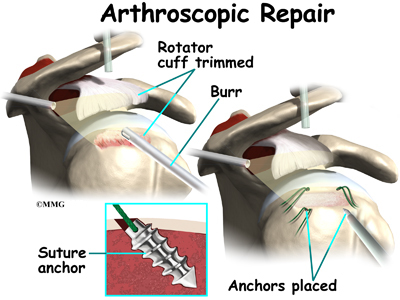

Once any degenerative tissue and bone spurs are removed, the torn rotator cuff tendon can be reattached to the bone. Special devices have been designed to reattach these ligaments. These devices are called suture anchors.

Suture anchors are special devices that have been designed to attach tissue to bone. In the past, many different ways were used to attach soft tissue (such as ligaments and tendons) to bone. The usual methods have included placing stitches through drill holes in the bone, special staples and screws with special washers – all designed to hold the tissue against the bone until healing occurred. Most of these techniques required larger incisions to be able to see what was going on and to get the hardware and soft tissue in the right location.

Today, suture anchors have simplified the process and created a much stronger way of attaching soft tissue to bone. These devices are small enough that the can be placed into the appropriate place in the bone through a small incision using the arthroscope. Most of these devices are made of either metal or a special plastic-like material that dissolves over time. This is the “anchor” portion of the device. The anchor is drilled into the bone where the surgeon wished to attach the soft tissue. Sutures are attached to the anchor and threaded through the soft tissue and tied down against the bone.

Open Repair

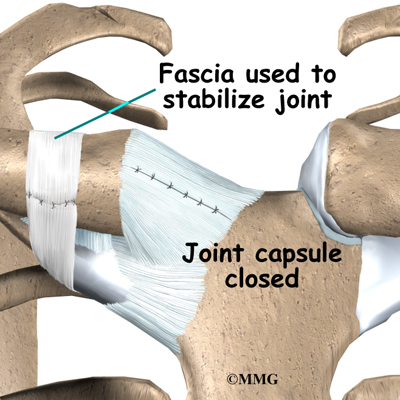

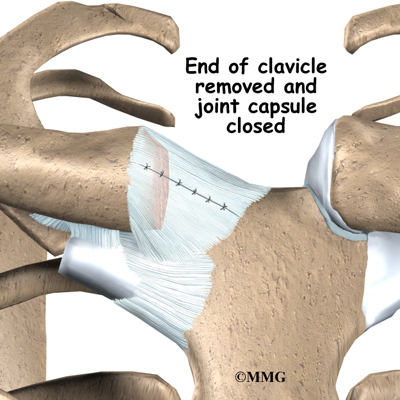

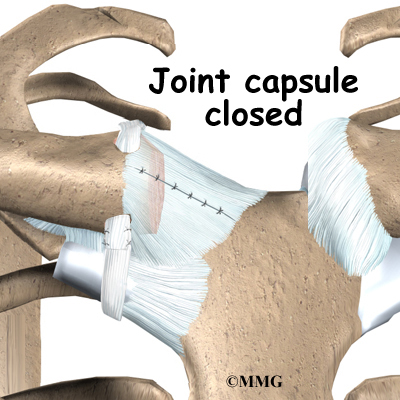

In some instances, open surgery is necessary. In open surgery, the surgeon gets to the rotator cuff tendon by cutting through muscles and tissues on the front of the shoulder. After repairing the tendon, the muscle on the front is reattached to the bone.

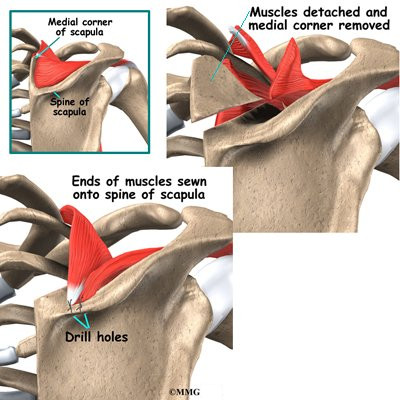

Graft Method

It is not possible to repair all rotator cuff tears. Sometimes the tendon has been torn for too long a period of time. The tendons and muscles become contracted and can’t be stretched enough to be reattached. In these cases, the surgeon may use a length of tendon graft to span the distance from the tendon stump of the torn rotator cuff to the humerus.

Salvage Procedure

In other cases, the tendon tissue has simply worn away, and the remaining tendon is not strong enough to hold the necessary stitches. In these instances, simply removing all the torn tissue and fixing any other problems in the shoulder may reduce your pain. But this will probably not increase the strength or motion of your shoulder. It may actually decrease your range of motion.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Even if you don’t need surgery, you may need to follow a program of rehabilitation exercises. Your doctor may recommend that you work with a physical or occupational therapist. Your therapist can create an individualized program to help you regain shoulder function. This includes tips and exercise for improving posture and shoulder alignment. It is also very important to improve the strength and coordination in the rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles. Your therapist can also evaluate your workstation or the way you use your body when you do your activities and suggest changes to avoid further problems.

After Surgery

Rehabilitation after rotator cuff surgery can be a slow process. You will probably need to attend therapy sessions for two to three months, and you should expect full recovery to take up to six months. Getting the shoulder moving as soon as possible is important. However, this must be balanced with the need to protect the healing tissues.

Your surgeon will most likely have you wear a sling to support and protect the shoulder for several weeks (generally four to six weeks) after surgery. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may be used during your first few therapy sessions to help control pain and swelling from the surgery. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

Therapy can progress quickly after arthroscopic procedures. Treatments start out with range-of-motion exercises and gradually work into active stretching and strengthening. You just need to be careful about doing too much, too quickly.

Therapy goes slower after surgeries where the front shoulder muscles have been cut. Exercises begin with passive movements. During passive exercises, your shoulder joint is moved, but your muscles stay relaxed. Your therapist gently moves your joint and gradually stretches your arm. You may be taught how to do passive exercises at home.

Active therapy usually starts six weeks after surgery. You use your own muscle power in active range-of-motion exercises. You may begin with light isometric strengthening exercises. These exercises work the muscles without straining the healing tissues. Formal strengthening exercises will be delayed until 12 weeks.

Exercises focus on improving the strength and control of the rotator cuff muscles and the muscles around the shoulder blade. Your therapist will help you retrain these muscles to keep the ball of the humerus firmly in the socket. This helps your shoulder move smoothly during all your activities.

Some of the exercises you’ll do are designed to get your shoulder working in ways that are similar to your work tasks and sport activities. Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don’t put too much stress on your shoulder. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

If all of these efforts to improve your shoulder condition fail, there are a few other options. Tendon grafts and muscle transfers, for example, may help you regain use of your shoulder. However, these procedures are very complex and are rarely necessary.