Shoulder

Osteonecrosis of the Humeral Head

A Patient’s Guide to Osteonecrosis of the Humeral Head

Introduction

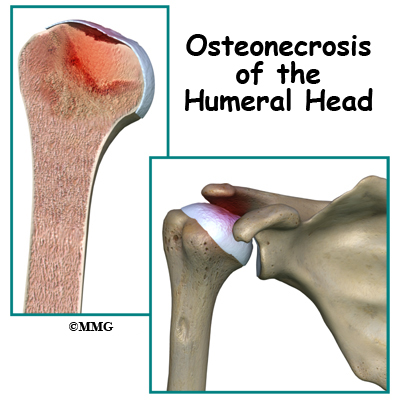

Osteonecrosis of the humeral head is a condition where a portion of the bone of the humeral head (the top of the humerus or upper arm bone) loses its blood supply, dies and collapses. Another term used for osteonecrosis is avascular necrosis. The term avascular means that a loss of blood supply to the area is the cause of the problem and necrosis means death.

This condition has been reported in all age groups but seems more common between the ages of 20 and 50. Men are affected by osteonecrosis of the shoulder twice as often as women but women with osteonecrosis from an autoimmune disease (e.g., lupus) develop this condition more often than men with the same disease.

This guide will help you understand

- how osteonecrosis develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

Where does this condition occur?

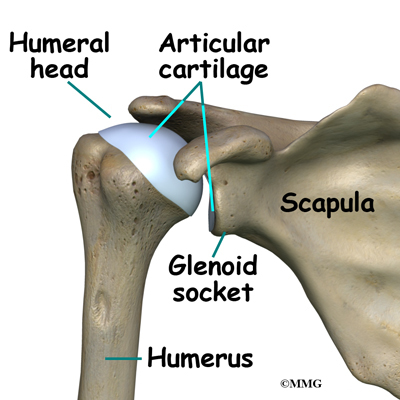

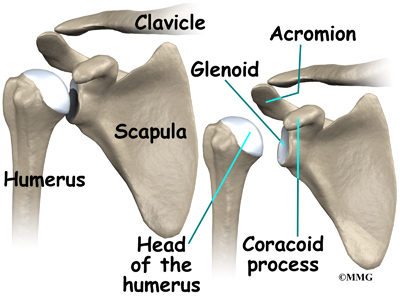

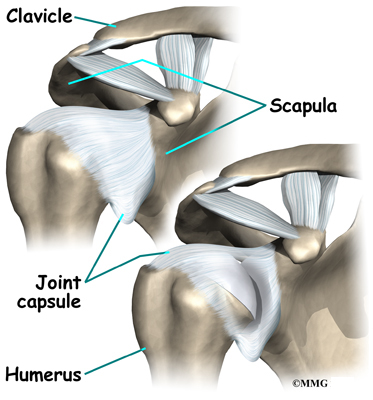

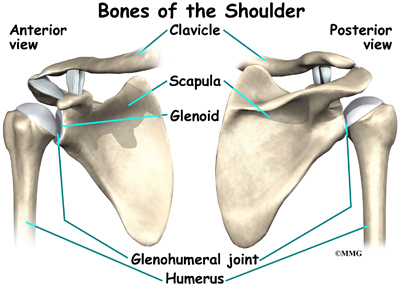

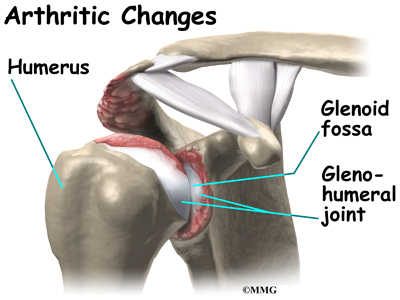

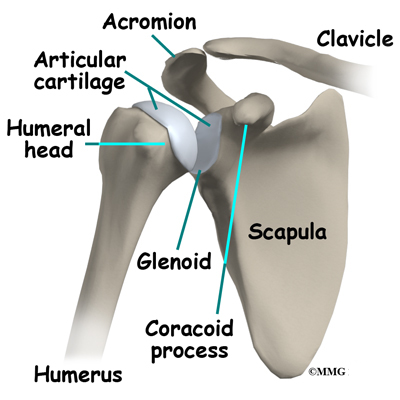

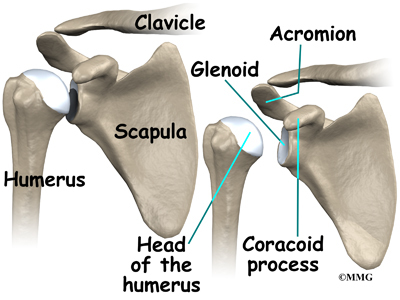

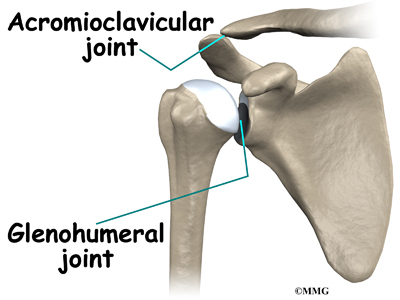

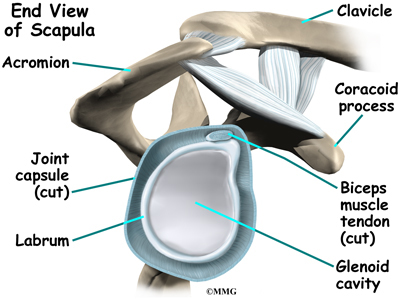

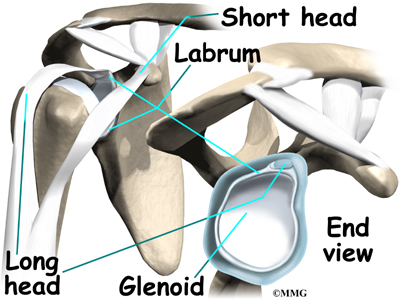

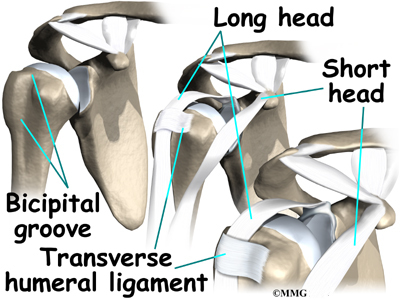

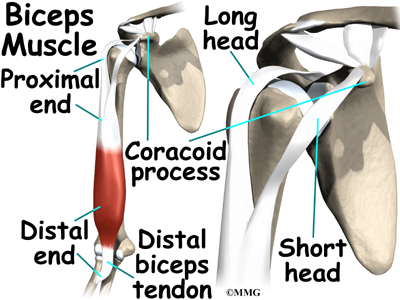

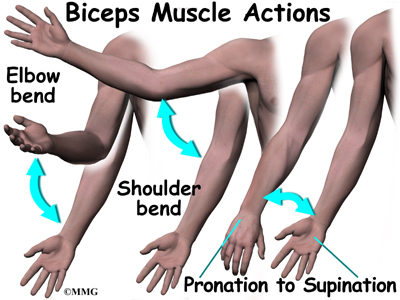

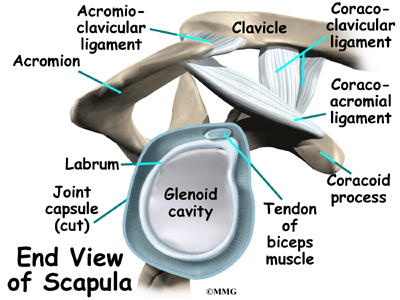

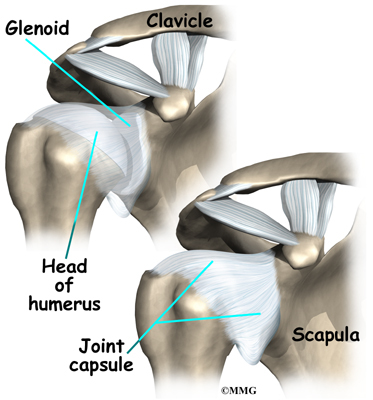

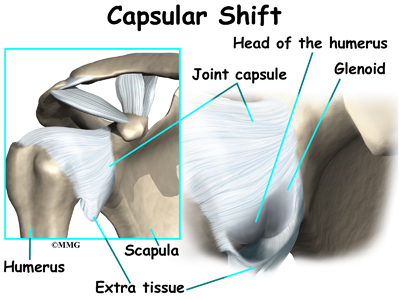

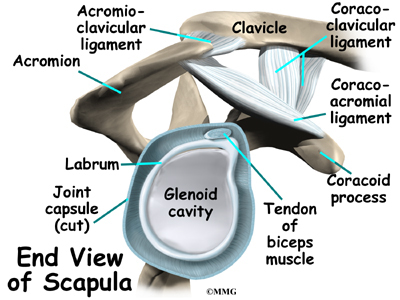

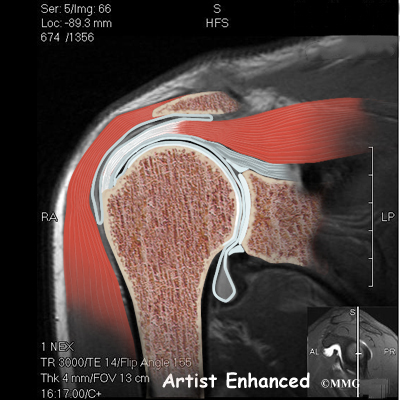

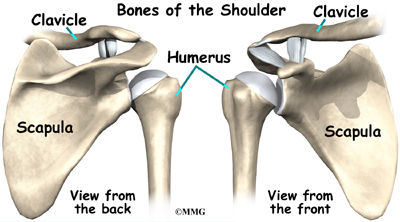

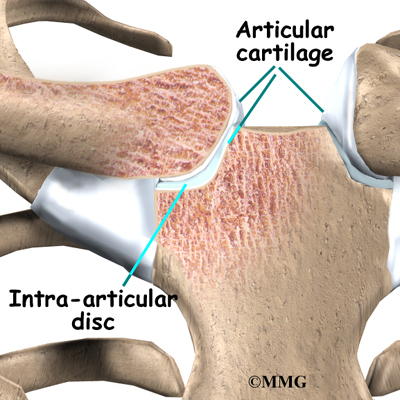

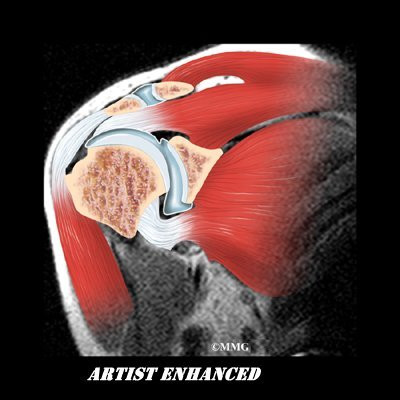

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint. The ball portion of the joint is called the humeral head. The humeral head is the uppermost part of the humerus, or upper arm bone. The shoulder socket is called the glenoid fossa. This socket is shallow and is part of the scapula (shoulder blade). The surface of the humeral head and the inside of the fossa are covered with articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is a tough, slick material that allows the surfaces to slide against one another with very little friction. The cartilage is about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large weight-bearing joints, but a bit thinner in the shoulder, which normally doesn’t support much weight.

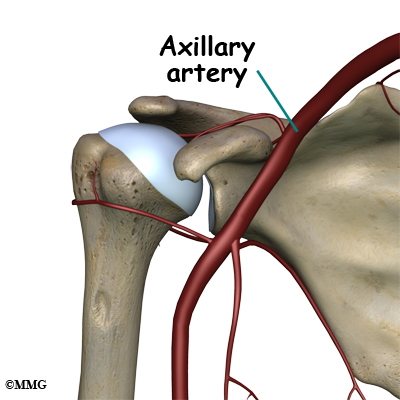

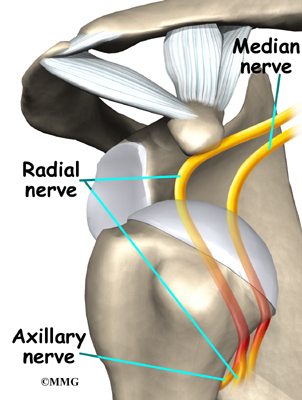

Large blood vessels supply the arm with blood. The large axillary artery travels through the axilla (armpit). If you place your hand in your armpit, you may be able to feel the pulsing of this large artery. The axillary artery has many smaller branches that supply blood to different parts of the shoulder. The shoulder has a very rich blood supply. But if this blood supply is damaged, there is no backup.

Causes

What causes this condition?

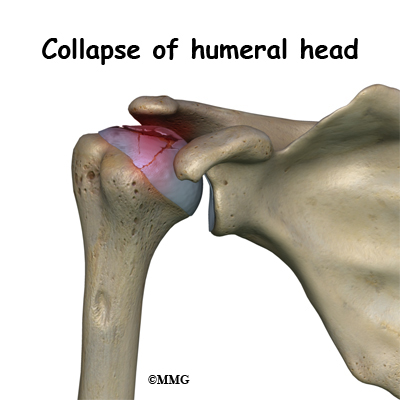

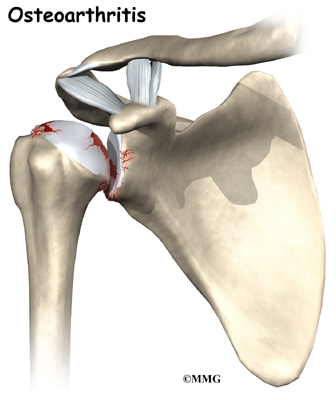

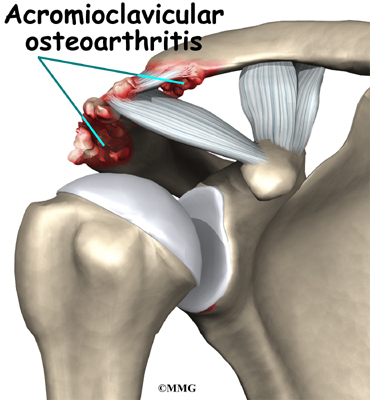

When osteonecrosis occurs in the shoulder joint, the top of the humeral head (the ball portion) collapses and begins to flatten. The flattening creates a situation where the ball no longer fits perfectly inside the socket. Like two pieces of a mismatched piece of machinery, the joint begins to wear itself out. This leads to osteoarthritis of the joint and pain.

Bone tissue is constantly being remodeled – old bone is removed and replaced with new bone. Osteonecrosis occurs when there is a loss of blood circulation in the bone of the humeral head. This causes the cells that remove and produce new bone to die in the area of lost circulation. New bone is no longer produced, but the old bone matrix still survives. Without the constant ability to repair itself through remodeling, the dead bone matrix eventually begins to lose strength and crumble. This causes the bone matrix to collapse. New blood vessels begin to grow into the area, but this is a slow process. The situation becomes a race to see whether new blood vessels will grow into the area and restore the ability to remodel the bone or whether collapse will occur.

The articular cartilage on the surface of the humeral head does not rely on the blood supply of the bone to survive. The articular surface is nourished by the synovial fluid; it survives the loss of blood flow to the bone. But, the articular cartilage relies on the bone underneath to keep its round shape. When the bone underneath collapses, the articular cartilage loses its round shape and no longer fits, or matches, the shape of the glenoid socket. The constant abnormal friction between the two mismatched joint surfaces causes mechanical wear and tear in both the humeral head and the glenoid socket. This degeneration is called osteoarthritis.

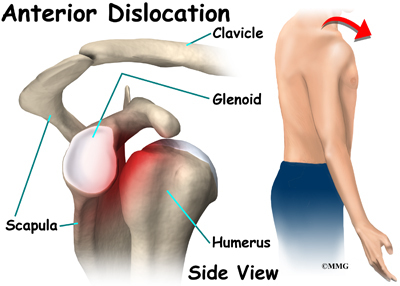

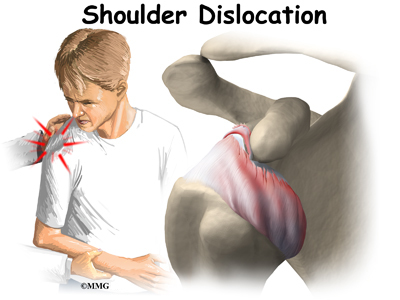

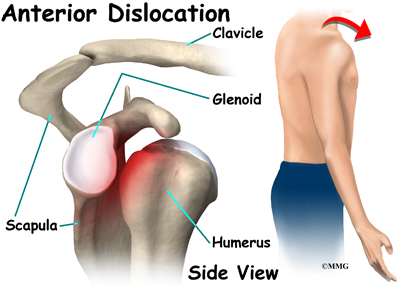

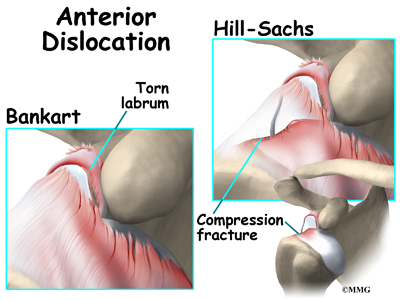

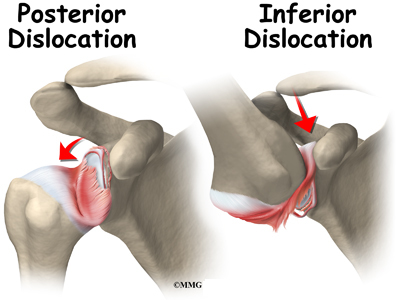

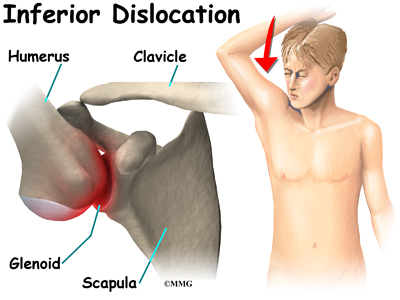

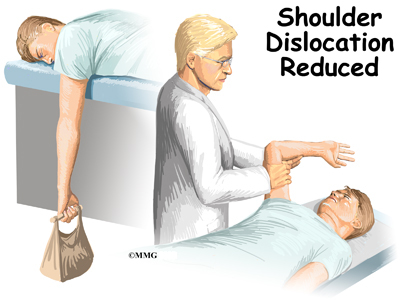

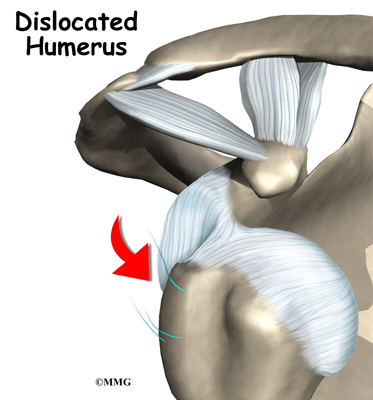

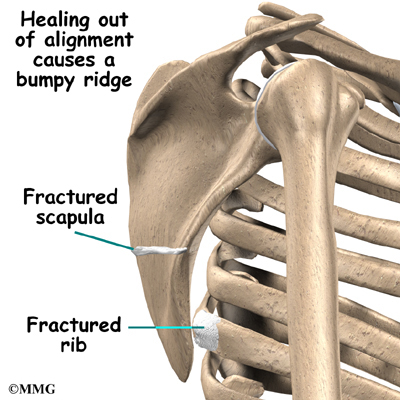

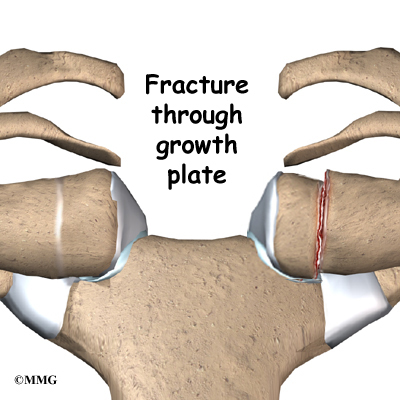

There are two forms of humeral head osteonecrosis: traumatic and atraumatic. The traumatic type can develop after an injury such as a bone fracture or shoulder dislocation. The nontraumatic form occurs with the use of corticosteroids, or it can be associated with other diseases or blood disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease, problems with coagulation or making blood clots). Sometimes it develops with no known cause. In those cases, it is called idiopathic (unknown cause).

There does seem to be a genetic link but exposure to certain risk factors is also part of the picture. For example, alcohol abuse, tobacco use, chemotherapy, radiation, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and organ transplantation are considered associated risk factors. A clear link exists between osteonecrosis and alcoholism. Excessive alcohol intake somehow damages the blood vessels and leads to osteonecrosis. Organ recipients must be on lifelong steroids to prevent inflammation, infection, and rejection of the organ. These medications have the adverse side effect of endangering blood supply and weakening the bone.

Symptoms

What does osteonecrosis feel like?

The first symptom of osteonecrosis of the humeral head is shoulder and arm pain. The location of the pain is difficult to isolate. You may not be able to point to it with one finger. You may feel like the pain is deep and throbbing. You may have difficulty reaching your arms out to the sides or overhead.

At first, the symptoms seem to come and go, but as the problem progresses (gets worse), the symptoms become more constant and stiffness develops in the shoulder joint. Pain may radiate, or travel, from your shoulder down to your elbow. There may be a sound and sensation of crunching called crepitus and locking in the joint. With arthritic changes, range of motion decreases. Eventually, the pain will also be present at rest and may even interfere with sleep. In a small number of cases, there are no symptoms despite X-rays that show advanced disease.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose this condition??

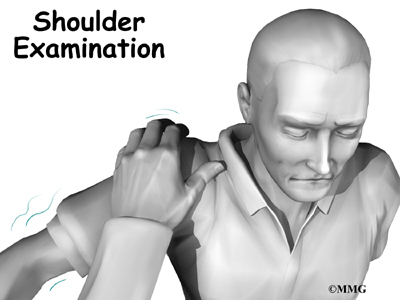

Your doctor will conduct a thorough history and carry out a clinical exam. The history helps identify associated risk factors, which will have to be addressed during treatment in order to get the most successful results. Your doctor will also check other joints for any signs of similar problems. In about half the patients, osteonecrosis is also present at the hip, knee, ankle, wrist, and/or elbow.

Lab studies can be done to rule out infection or test for systemic diseases or blood disorders that can cause osteonecrosis.

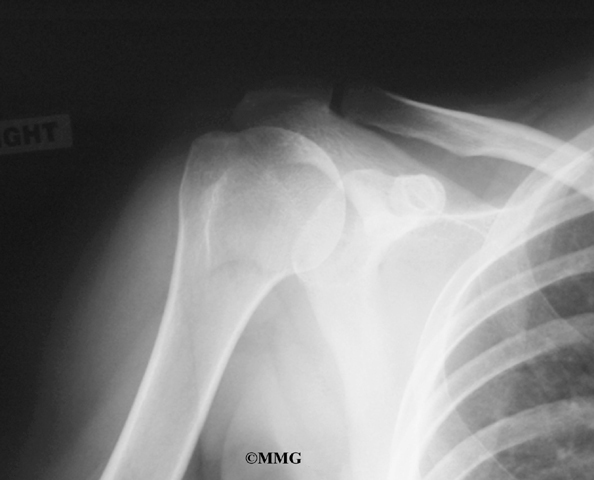

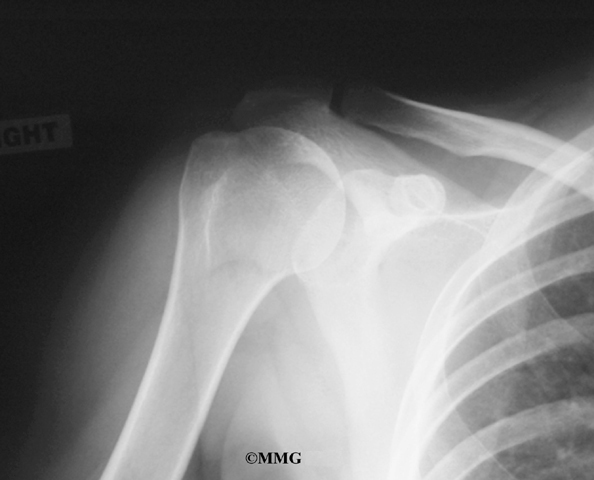

Standard X-rays are usually ordered to confirm the diagnosis. Several different views are needed. Besides the usual anterior-posterior (AP) views, radiographs should include views with the joint in external (outward) and internal (inward) rotation. That will help show all areas of the diseased humeral head, important information for planning treatment.

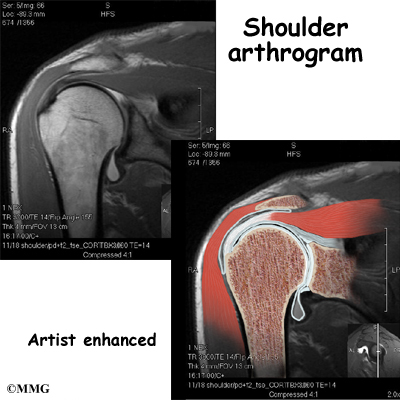

X-rays don’t always show all of the changes until the condition has been present for quite some time. MRIs may be used to define more clearly early changes in fat and water content of the bone marrow that won’t be seen on X-ray. Bone scans have fallen out of favor for the detection and diagnosis of osteonecrosis. Studies show only one-third of true cases are successfully identified with this imaging tool.

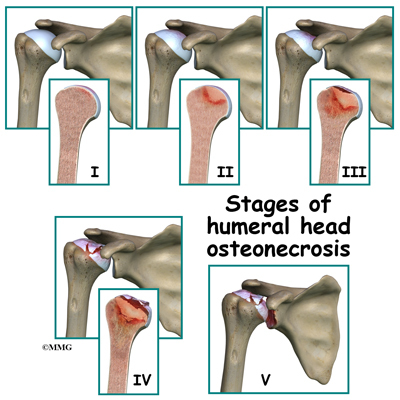

Treatment is based on the severity of disease, so part of the diagnosis is to identify what stage the disease is in. The stages start with stage I, which means no changes are seen on X-ray images and go up to stage V. In stage V (the most advanced disease) the humeral head is collapsed and the socket is damaged as well. There may be soft tissue tears present in the more advanced stages.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

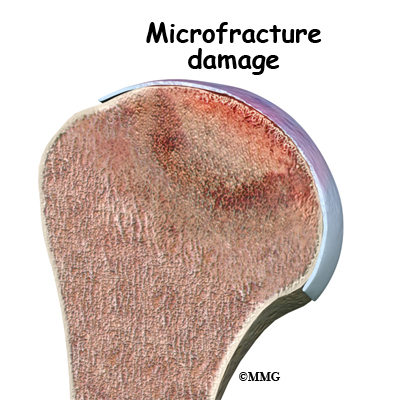

The first goal in treating osteonecrosis of the humeral head is to save the bone. Left untreated, the disease process will continue until the layer of bone just under the joint surface cracks causing small microfractures. Once enough microfactures happen, the bone begins to collapse and the articular cartilage covering the joint surface also starts to collapse. Eventually, there will be damage to the entire shoulder joint. The second goal is to keep shoulder function while relieving pain. Various nonsurgical and surgical methods have been used to treat this problem.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The first line of treatment is medication to restore blood supply and allow new bone growth. Some of the more common drugs used include lipid-lowering (cholesterol-lowering) agents, vasodilators (opens up the blood vessels), anticoagulants (prevents blood clotting), and bisphosphonates (prevents bone loss). The type of medication used depends on the underlying systemic disease causing the bone problem. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may provide some symptom relief of the osteoarthritis but they do not slow or stop the osteonecrosis.

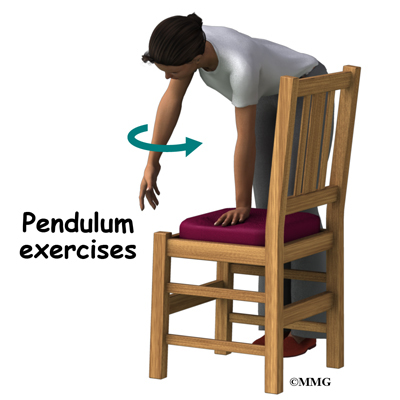

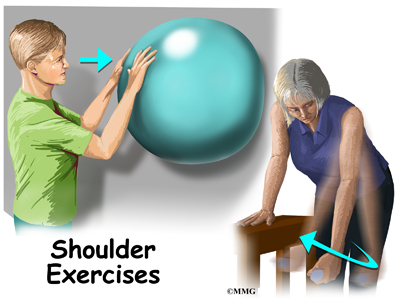

Depending on your symptoms and limitations in motion and strength, you may be started on a series of exercises called pendulum exercises. These are designed to help keep full motion in the shoulder joint but without stressing the joint. You may be told to avoid lifting your arm overhead or away from the body against resistance. You should also avoid lifting or holding anything heavy. Your doctor may give you a weight restriction (i.e., don’t lift anything more than two to five pounds). Putting away heavy groceries for example should be avoided at this time.

Physical therapy that include modalities for pain control and progression of range-of-motion exercises with subsequent strengthening is helpful in all stages, particularly in stage I and stage II.

Patients are advised to stop using tobacco or alcohol. Anyone taking corticosteroids should consult with the prescribing physician to review the need for and use of these medications because of their possible adverse effect on bone.

Surgery

Core Decompression

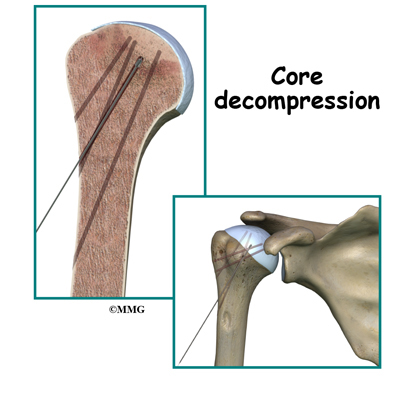

Surgical intervention may be needed in the more advanced stages of osteonecrosis. When the condition is in the early stages, a procedure called core decompression is used to reduce bone marrow pressure and allow the formation of new blood supply to the area. The new blood vessels help the necrotic area start to form new, healthy bone.

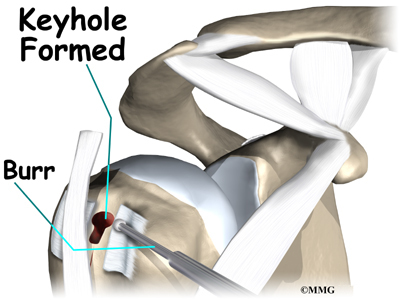

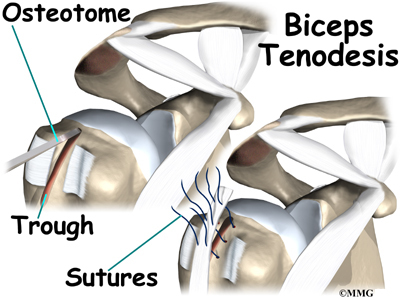

Core decompression is done by drilling small holes from the healthy bone to the area of necrosis in the humeral head. This creates channels that allow new blood vessels to grow into the necrotic area. The surgeon uses a special type of X-ray called fluoroscopy to guide the placement of the pins used to drill the holes. Removing some of the dead bone also causes bleeding into the region of necrotic bone and stimulates new bone growth.

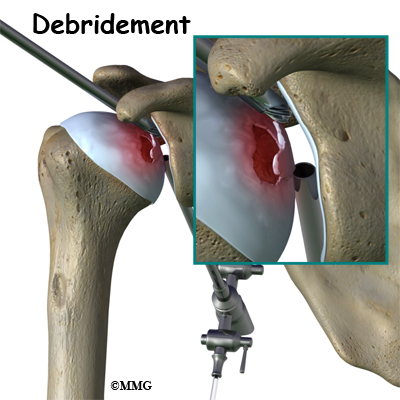

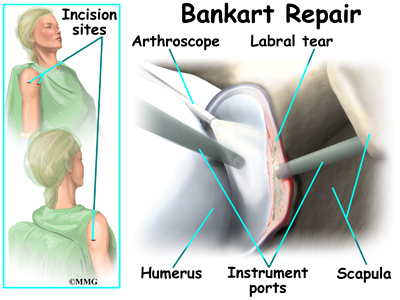

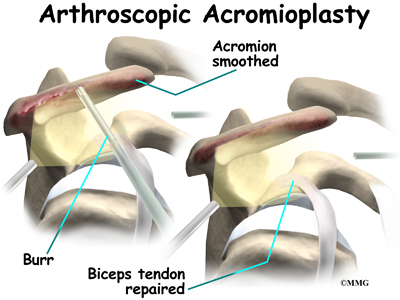

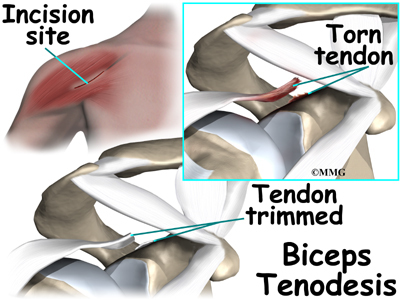

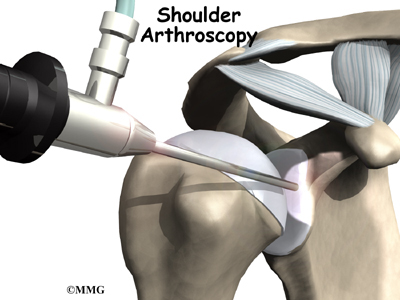

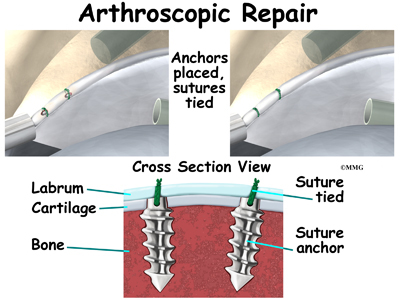

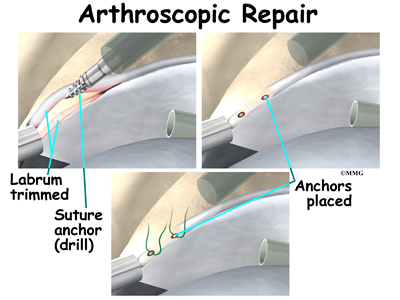

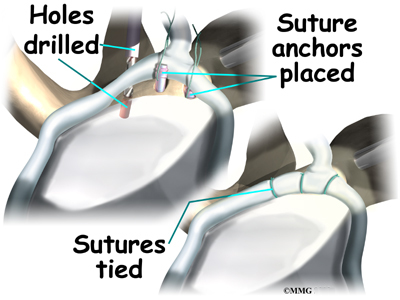

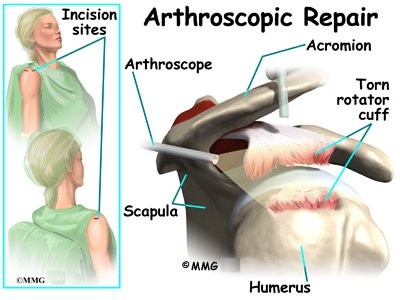

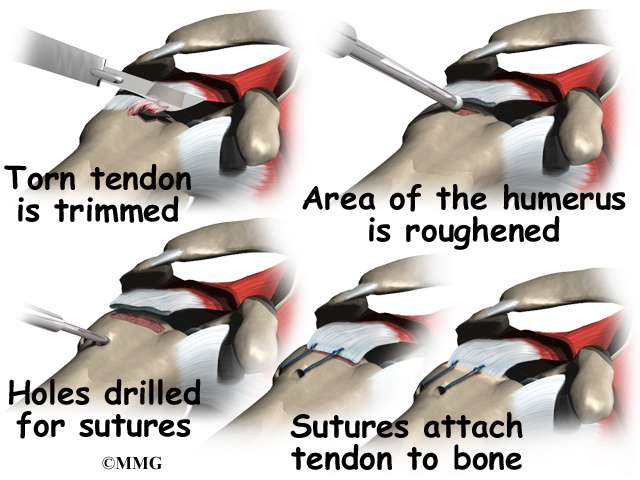

Arthroscopy

If there are any loose bits of bone or cartilage in the joint, then the surgeon may have to perform arthroscopic debridement . The arthroscope is a small fiberoptic camera that can be inserted into the joint allowing the surgeon to see the inside of the joint. Other instruments can be inserted into the joint though small incisions to remove tissue and smooth the surface of the joint. The shoulder joint is cleaned up of any debris. Any frayed edges of joint cartilage are smoothed down. Sometimes the surgeon combines these two procedures (decompression and arthroscopy). The arthroscopic exam shows the location and extent of the disease in the joint while the decompression addresses the necrotic area of bone.

Bone Grafting

Bone grafting replaces the necrotic (dead) bone with donor bone that is usually taken from the patient’s own hip. This treatment approach is used for mild to moderate disease. It is not advised for late stage disease as studies show patients with more advanced disease do better with arthroplasty (joint replacement). The bone graft gives the joint surface support needed to keep it from collapsing. With that support in place, the bone can begin to heal.

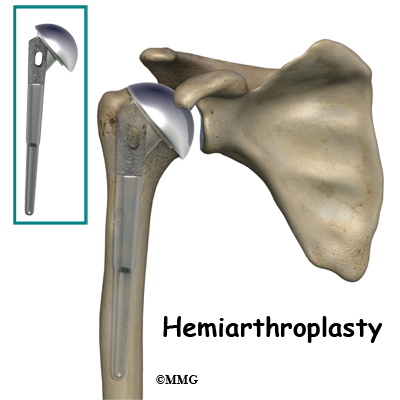

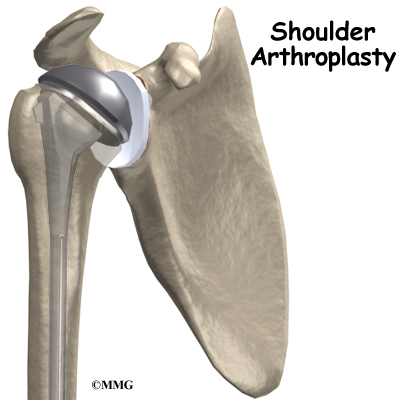

Arthroplasty

Joint replacement is used for more severe damage of the the joint. A hemiarthroplasty (partial replacement) may be all that’s needed when only one side of the joint has been affected. Full joint replacement is reserved for patients with significant involvement of both the humeral head and the glenoid fossa (socket).

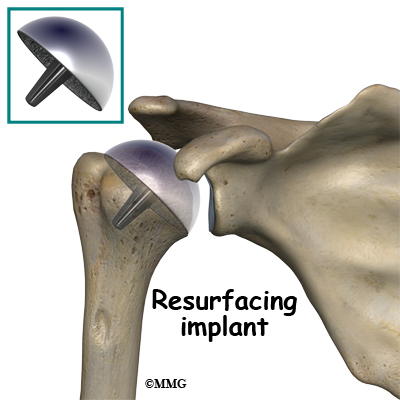

A newer procedure called humeral head resurfacing is gaining popularity and may help save the joint. Instead of removing the head of the humerus and replacing it, the bone is smoothed down and a metal cap placed over the smoothed head like a tooth capped by the dentist. The cap is held in place with a small peg that fits down into the bone. Joint resurfacing requires that the patient have enough healthy bone to support the cap.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Studies show that the results of nonsurgical treatment are satisfactory when the disease is caught during the early stages. Symptoms often remain mild, even when the disease is advanced. Since the shoulder does not involve weight-bearing like the hip, good results are obtained with conservative care. Physical therapy may be needed for extended periods of time. There are some patients who will continue to progress despite early conservative care. Predicting who might develop more advanced disease is difficult, so close monitoring is advised.

After Surgery

After core decompression, you may be wearing a sling for a few days. Many patients report immediate pain relief. Active-assisted motion is allowed in all directions. Active-assisted means you use your other hand (or hold a cane or some other type of stick with both hands) to help guide the involved side through the motion. Movements are not forced. You’ll go as far as you can comfortably.

You will gradually resume all normal activities over a period of four or five weeks — as long as you remain pain free. High-impact activities or activities that load the joint are not allowed for a full year following decompression.

With any of the more invasive procedures such as joint replacement, passive range-of-motion is carried out under the supervision of a physical therapist. Because major muscles are cut and reattached during the operation, regaining motion is progressed slowly to protect the healing soft tissues.

Active motion (moving under your own muscle power without help) is not allowed for the first three weeks. In fact, the therapist will move you from passive motion through active-assistive motion and then to active motion over a period of six weeks. Stretching and strengthening don’t begin until around week 12 post-op.

Results of treatment are often good but patients should be prepared for the possibility that the condition can progress over time. Further surgery may be needed. For those who have decompression or bone grafting, joint replacement may be needed eventually.

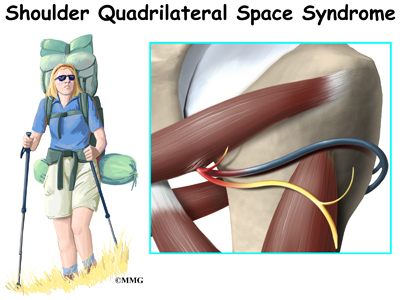

Quadrilateral Space Syndrome

A Patient’s Guide to Quadrilateral Space Syndrome

Introduction

Quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS) happens when the axillary nerve is compressed, or injured in the back of the shoulder. Sometimes the symptoms are caused by the compression of an artery in the same area.

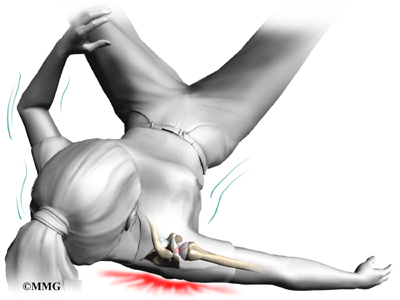

Quadrilateral space syndrome usually happens from overuse, especially with overhead sports like throwing and swimming. The syndrome can also be caused by an injury, like a shoulder dislocation.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the shoulder are involved

- what causes this condition

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the shoulder are involved?

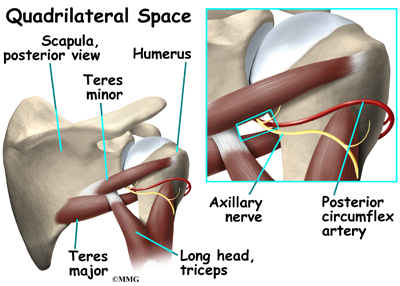

A quadrilateral is a four-sided shape. The quadrilateral space of the shoulder is in the upper back, where the shoulder meets the body. Three of the sides of the quadrilateral space are formed by muscles. The top of the quadrilateral is bordered by a muscle called the teres minor. The teres major muscle forms the bottom border. Part of the triceps muscle forms the inside border. The long bone of the upper arm, called the humerus, makes up the outer border.

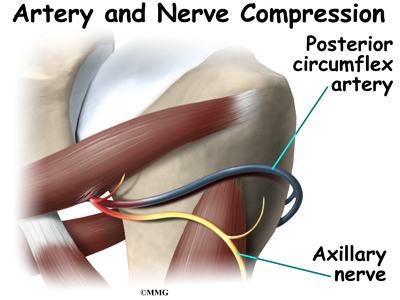

In addition to these muscles, the axillary nerve and the posterior circumflex humeral artery are in the quadrilateral space. When either the nerve or the artery is compressed or injured in this area it can cause problems such as quadrilateral space syndrome.

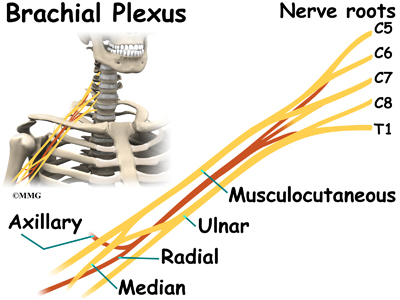

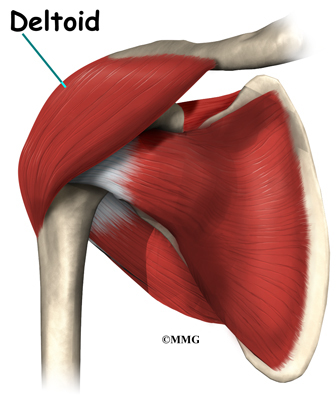

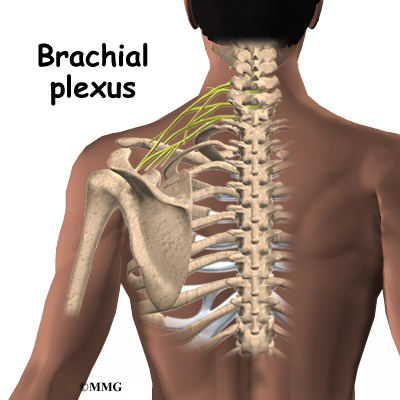

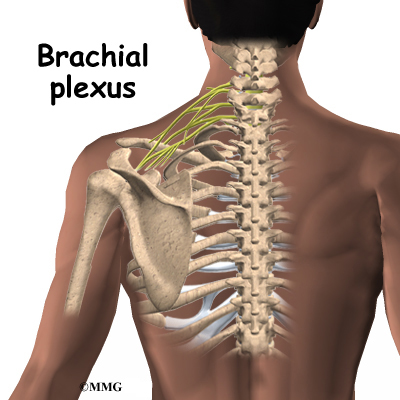

The axillary nerve is considered a peripheral nerve. There are several peripheral nerves in the shoulder that can be injured. The spinal cord in the neck, or cervical area, has branches that are called nerve roots. The nerve roots in the neck come together to form a large peripheral nerve called the brachial plexus. The axillary nerve is one of the branches off the brachial plexus. The axillary nerve is mainly formed from the fifth (C5) and sixth (C6) cervical nerve roots. The axillary nerve gives strength to the teres minor muscle and the deltoid muscle. It gives sensation to the shoulder joint.

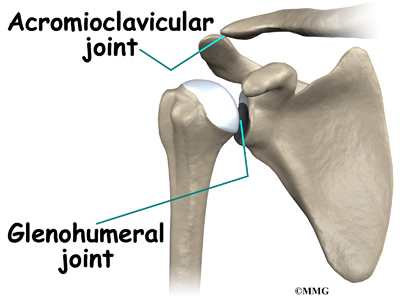

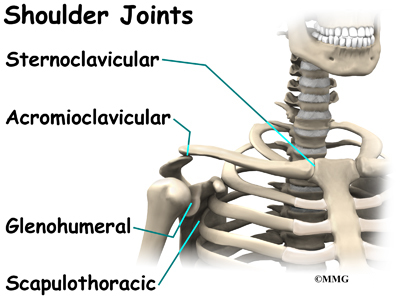

The shoulder joint is also known as the glenohumeral joint. It is a ball and socket joint. The glenoid is the cup portion of the shoulder joint. The upper end of the humerus forms the ball portion.

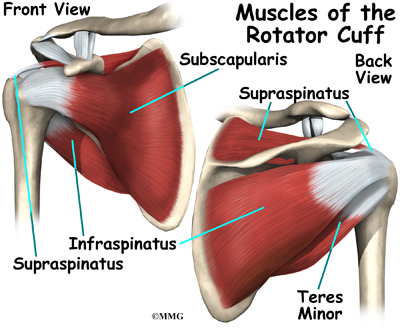

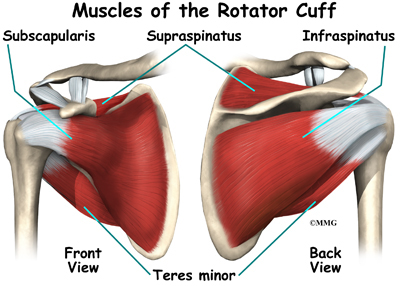

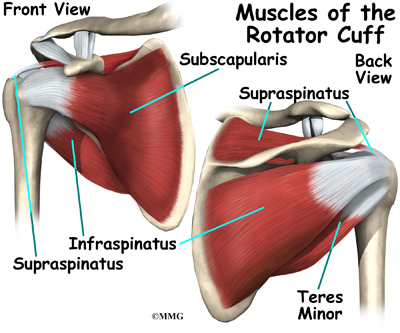

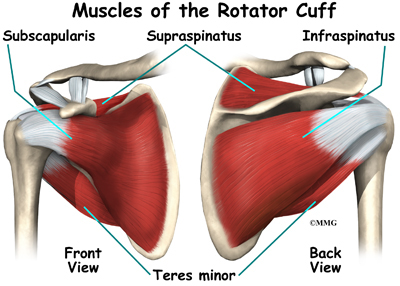

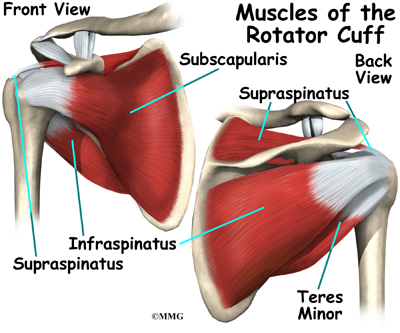

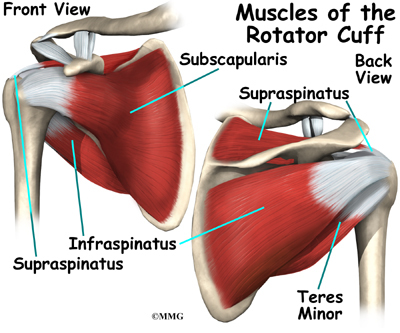

The shoulder joint is supported by many muscles. The most famous are the four rotator cuff muscles.They combine at the shoulder to form a thick cuff. They are also referred to as the SITS muscles. Each letter stands for one

of the rotator cuff muscles; supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. Sometimes injury to the quadrilateral space is mistaken as rotator cuff injury.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Causes

What causes this condition?

Repetitive stress or overuse is a major cause of quadrilateral space syndrome. Some of the more common causes of overuse are seen in overhead sports like throwing and swimming. Children specializing in certain sports at early ages, have increased risk of getting quadrilateral space syndrome. Sometimes poor training techniques are to blame. Bands of extra fibers are usually what cause the compression of the axillary nerve, or the small artery in the quadrilateral space.

There are varying degrees of nerve injury. Most commonly, injury to the axillary nerve is a more mild form of injury called neuropraxia. This means that it typically recovers fully. The axillary nerve is very short, so even a severe injury can heal rather quickly.

An acute axillary nerve injury can also happen from carrying a heavy backpack. The misuse of crutches can also cause compression of the nerve.

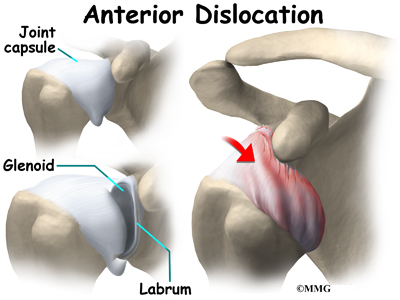

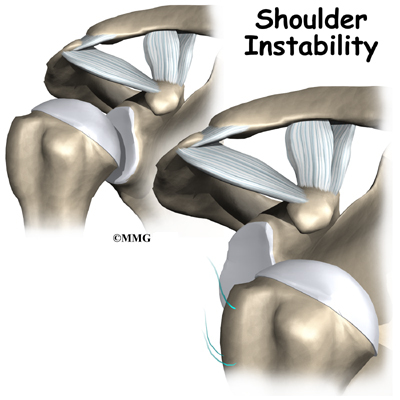

The most common traumatic injury that causes quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS) is a shoulder dislocation. Some reports show that quadrilateral space syndrome can happen 10 to 60 percent of the time after a shoulder dislocation. There is a greater risk depending on the type of dislocation.

A blunt force injury to the back of the shoulder can also cause quadrilateral space syndrome.

Symptoms

What does quadrilateral space syndrome feel like?

Symptoms of quadrilateral space syndrome usually include vague shoulder pain, numbness or tingling in the arm, and tenderness to pressure over the area of the quadrilateral space. A dull ache in the shoulder may worsen when the arm is moved overhead repeatedly.

Weakness and instability can sometimes be noted. The diagnosis of quadrilateral space syndrome is often missed since symptoms can be similar to other shoulder problems.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

Your doctor will complete a history and physical examination.

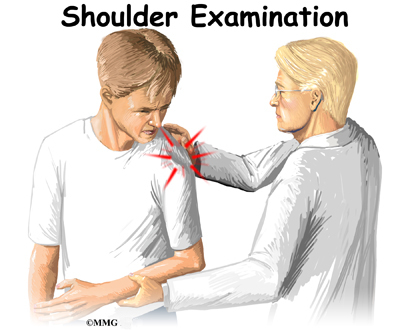

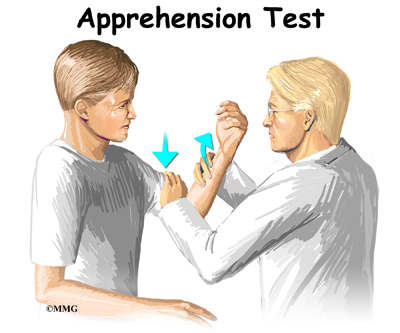

Your doctor will ask questions about activity, possible traumatic injury, and the symptoms you are having. The physical examination usually includes evaluating range of motion, strength testing, checking reflexes and sensation. During this examination pressure will be applied over various areas of the shoulder to see where it may be painful.

Weakness and instability can sometimes be noted. The diagnosis of quadrilateral space syndrome is often missed since symptoms can be similar to other shoulder problems. Often there will be wasting of the teres minor muscle, and sometimes the deltoid muscle. Subluxation (instability) of the glenohumeral joint is sometimes noted as well.

Your doctor may want you to have some special tests done in order to better evaluate what is causing your problems.

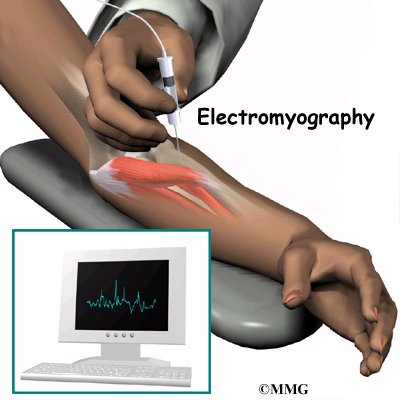

Electromyelogram (EMG) is a valuable tool in the diagnosis of quadrilateral space syndrome (QSS) and other peripheral injuries around the shoulder. The doctor will place small needle electrodes into various muscles to see how well they are functioning. Since different nerves make different muscles work, it help to narrow down where the problem is coming from.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans can sometimes identify the muscle wasting of the teres minor and deltoid muscles. MRI does not use x-rays. It uses magnetic waves. It allows the doctor to see your tissues and bones in thin slices.

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) is sometimes used to identify problems with the artery or vein within the quadrilateral space. Computed tomography uses special X-rays. The CTA requires that contrast dye be injected into a vein. Your arm will likely be in a throwing position while being scanned. Computed tomography also allows your doctor to see your bones and tissues in thin slices.

Some doctors do an axillary nerve block. The area of the axillary nerve is injected with a numbing medication like lidocaine. If the pain goes away when the nerve is numb, it is considered a postitive test. This helps the doctor determine whether or not it is the axillary nerve causing your symptoms.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Most of the time, quadrilateral space syndrome will improve with nonsurgical treatment.

There are varying degrees of nerve injury. Most commonly, injury to the axillary nerve is a more mild form of an injury called neuropraxia. This means that it typically recovers fully. The axillary nerve is very short, so even a severe injury can heal rather quickly.

It is important to rest your shoulder. Your doctor may suggest taking a break from the activity that may be causing your symptoms. Changing throwing or sport mechanics may be helpful.

Anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naprosyn may be suggested. Heat or cold packs to your shoulder may be beneficial.

Your doctor will likely prescribe physical therapy.

Surgery

If there is no improvement after six weeks of conservative care, surgery is usually recommended.

Bands of extra fibers in the quadrilateral space are usually what cause the compression of the axillary nerve or the small artery or vein. These bands of fibers are clipped or removed during surgery. This type of surgery is called decompression. It is quite effective.

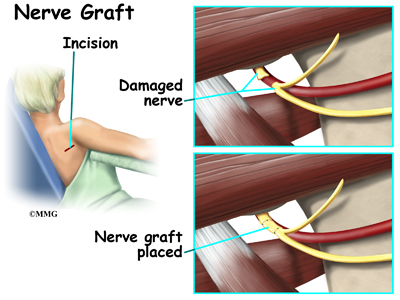

Occasionally, after high-energy trauma, or during surgery, the axillary nerve will be over-stretched, or even cut. This type of injury is called neurotomesis. The axillary nerve may need to be repaired. The injured portion is replaced with another nerve. This is called a nerve graft.

Your surgeon will operate from the back of the shoulder, making a small incision. In the case of nerve grafting, there will be a small incision where the other portion of nerve is removed. You will be allowed to go home the same day. Your arm will likely be in a sling.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect as I recover?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Physical therapy is helpful for maintaining shoulder range of motion, or flexibility. Posture training may also be helpful. Your physical therapist or trainer may have you change the way you do your overhead sport when overuse is a problem. Electrical muscle stimulation (EMS) may be beneficial when there is muscle weakness or wasting. EMS is a battery operated device that sends electrical current to your muscles to make them contract. This will help maintain strength and decrease wasting of the muscle. There are units that can be used at home.

After about four weeks, you may be able to do more exercise on your own. Usually by six weeks, exercises specific to your sport are introduced. In most cases, you can expect to be pain free, have full range of motion, and be able to resume activity in 12 weeks.

Return to sports varies. Your doctor may want to have the EMG repeated monthly to see if the axillary nerve is improving. Improvement in the EMG should be seen. Near full recovery of deltoid muscle strength is recommended before return to your sport.

Most of the time, conservative care such as physical therapy is all that is needed. Return to activity is the goal of treatment. Rarely is surgery needed.

After Surgery

Most shoulder rehabilitation includes three phases.

Phase I is to limit pain, and allow range of motion at the shoulder. Gentle motion is started to keep scar tissue from forming again. This also keeps the nerve and blood vessels moving freely. During the first four weeks after surgery, it is important not to overuse your arm. Working on posture may also be a part of your therapy.

Phase II includes gentle strengthening of the shoulder and upper extremity. Total body conditioning is also important. This often means riding a bike, walking on a treadmill, and even strengthening of the core muscles in your trunk.

Phase III is usually started six weeks after surgery. This includes sport specific activities, functional activities, and continued conditioning. Your physical therapist or trainer may have you change the way you do your overhead sport when overuse has been the problem.

Your doctor may want to have the EMG repeated at monthly intervals to see if the axillary nerve is improving, especially after surgery to graft the nerve. By twelve weeks, you should be pain free. You should have full range of motion of the shoulder. Return to sports varies. However, in general, it is recommended there be improvement in the EMG, and that the muscle strength of the operated shoulder is at least 80 percent of the muscle strength of nonoperated shoulder.

Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

A Patient’s Guide to Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Introduction

Shoulder joint replacement surgery (also called shoulder arthroplasty) can effectively ease pain from shoulder arthritis. Most people experience improved shoulder function after this surgery. But, certain patients are not candidates for joint replacement of the shoulder because they lack the muscle function necessary to stabilize the joint. A different type of shoulder replacement, called reverse shoulder replacement, may be available for many of these patients and provide pain relief as well as a stable functioning shoulder.

This guide will help you understand

- how the shoulder works

- what parts of the shoulder are replaced in reverse shoulder replacement

- how reverse shoulder replacement differs from shoulder replacement

- what to expect after reverse shoulder replacement surgery

Anatomy

What parts of the shoulder are involved?

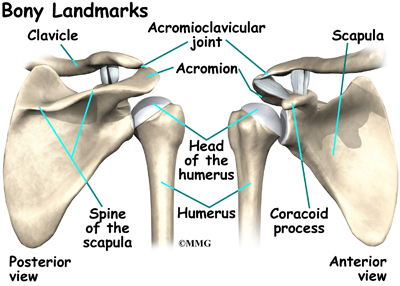

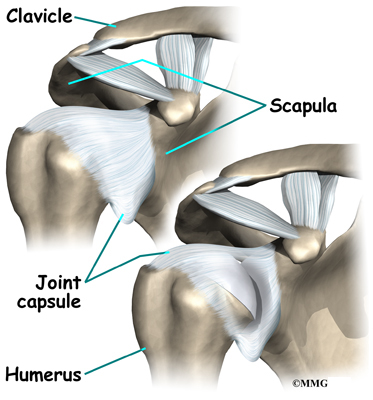

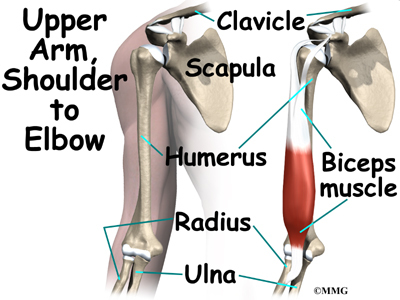

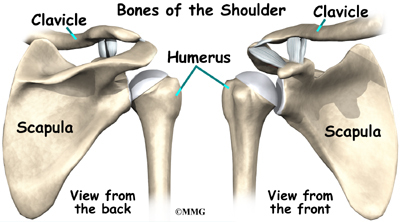

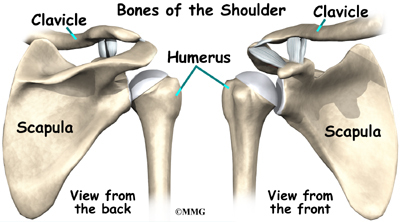

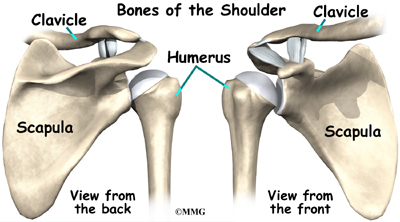

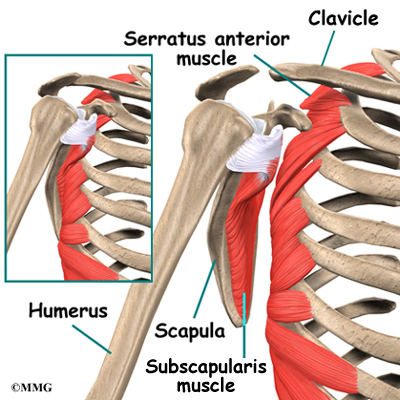

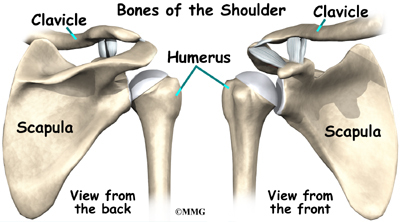

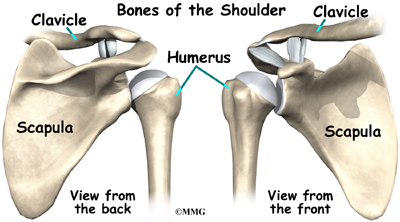

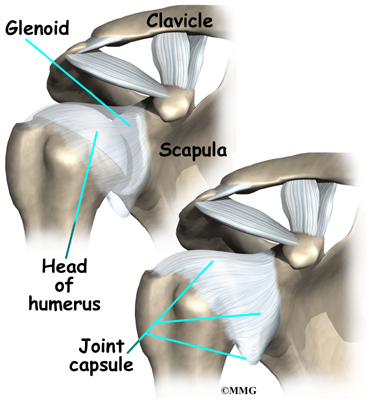

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone).

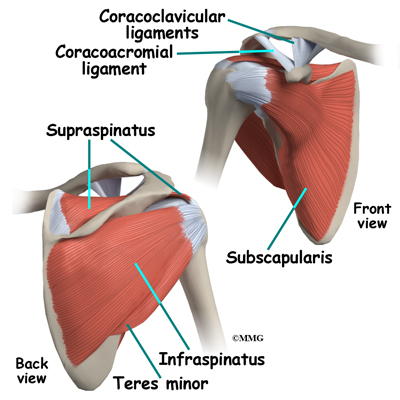

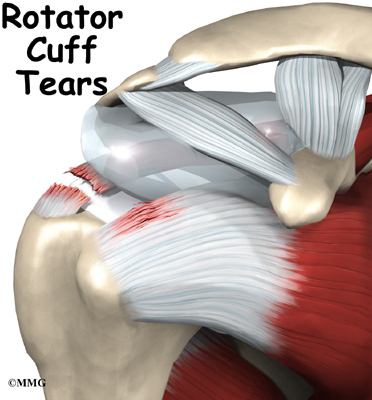

The rotator cuff connects the humerus to the scapula.

The rotator cuff is formed by the tendons of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

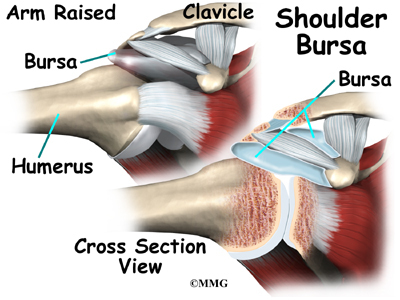

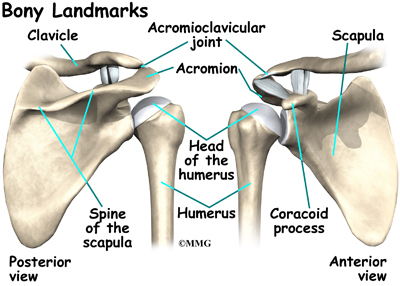

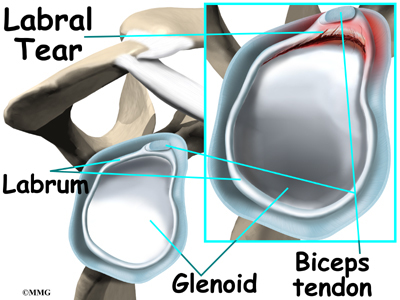

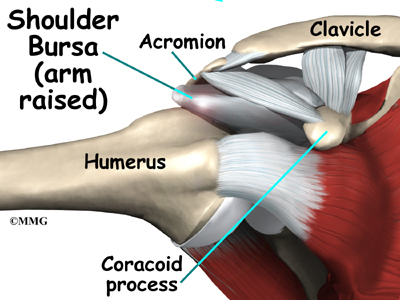

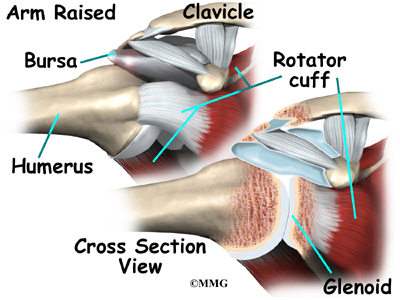

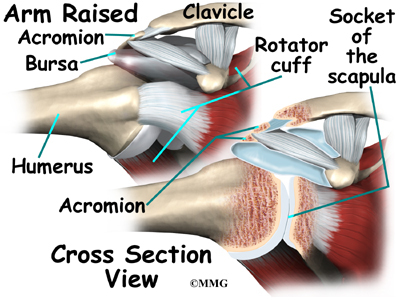

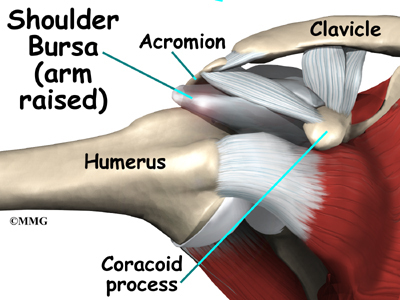

Muscles move bones by pulling on the tendons. The rotator cuff helps raise and rotate the arm. As the arm is raised, the rotator cuff also keeps the humerus tightly in the socket. A part of the scapula, called the glenoid, makes up the socket of the shoulder. The glenoid is very shallow and flat.

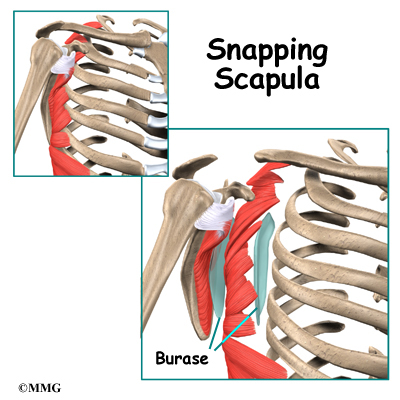

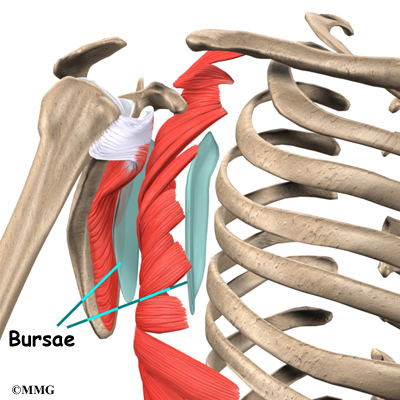

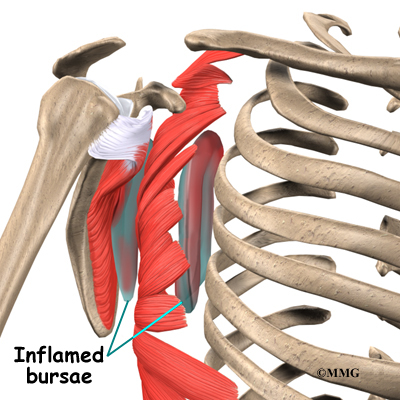

The part of the scapula that connects to the shoulder is called the acromion. A bursa is located between the acromion and the rotator cuff tendons. A bursa is a lubricated sac of tissue that cuts down on the friction between two moving parts. Bursae are located all over the body where tissues must rub against each other. In this case, the bursa protects the acromion and the rotator cuff from grinding against each other.

The humeral head of the shoulder is the ball portion of the joint. The humeral head has several blood vessels, which enter at the base of the articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is the smooth, white material that covers the ends of bones in most joints. Articular cartilage provides a slick, rubbery surface that allows the bones to glide over each other as they move. Cartilage also functions as sort of a shock absorber.

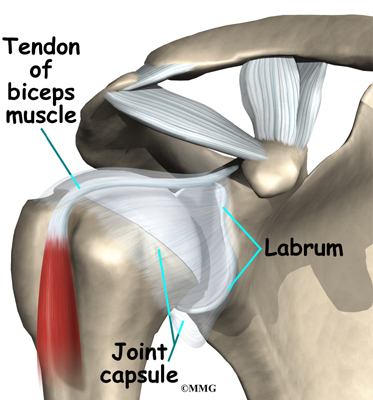

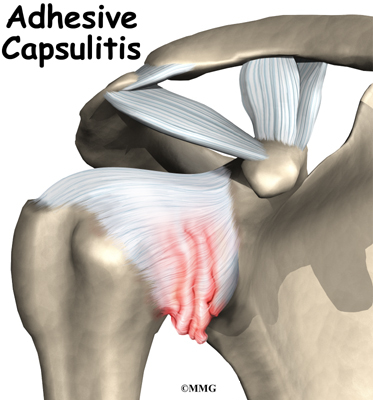

The shoulder joint is surrounded by a watertight sac called the joint capsule. The joint capsule holds fluids that lubricate the joint. The walls of the joint capsule are made up of ligaments. Ligaments are connective tissues that attach bones to bones. The joint capsule has a considerable amount of slack, loose tissue, so that the shoulder is unrestricted as it moves through its large range of motion.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Rationale

What conditions lead to reverse shoulder joint replacement?

The most common reason for undergoing shoulder replacement surgery is osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is caused by the degeneration of the joint over time, through wear and tear. Osteoarthritis can occur without any injury to the shoulder, but that is uncommon. Because the shoulder is not a weight-bearing joint, it does not suffer as much wear and tear as other joints. Osteoarthritis is more common in the hip and knee.

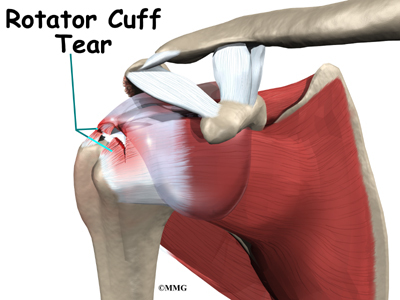

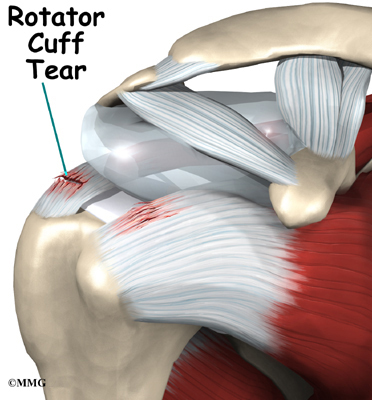

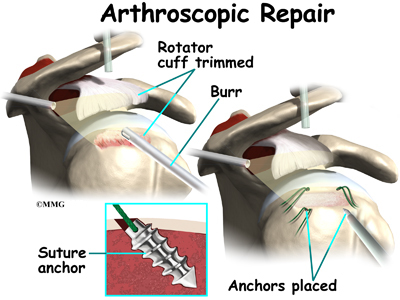

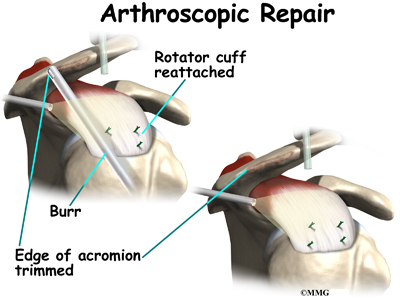

Rotator cuff problems are a common condition in the shoulder, especially as we grow older. Degeneration or wear and tear of the rotator cuff tendons occurs as we age. Over time this can lead to weakening of the tendons and may result in a rotator cuff tear. Surgery to repair a rotator cuff tear is fairly common in people who are middle aged and older. Most rotator cuff repairs are successful, but in a portion of patients, the tendon has become so degenerated that the tendon can simply not be repaired. Small, medium and many large tears can be repaired either through arthroscopic or open surgical procedures. Unfortunately, many large tears that are untreated for a long time may retract and become unfixable.

A shoulder joint without an intact rotator cuff may still function relatively well. Some patients will have weakness, some pain and may not be able to completely raise the arm. But, they get by without their rotator cuff fairly well. There are many people who choose not to have surgery to repair a rotator cuff tear and will simply live with the limitations. Patients with massive rotator cuff tears may not be able to lift the arm without significant pain and weakness. When the arm cannot be lifted, this is called a pseudoparalytic shoulder.

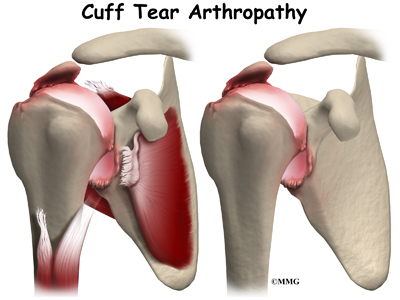

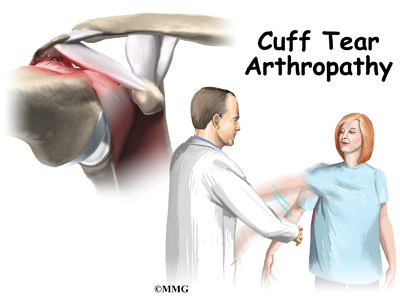

The shoulder needs a functioning rotator cuff to remain stable as well as to create a joint capsule to hold the joint fluid that lubricates the joint. Over time, a shoulder without an intact rotator cuff becomes arthritic – the shoulder joint wears out due to the abnormal motion, the instability, and lack of lubrication from the joint fluid. This type of wear and tear arthritis in the shoulder is called (rotator) cuff tear arthropathy.

Cuff tear arthropathy is difficult to treat. The shoulder is weak and painful. Patients may not be able to raise the arm above shoulder level. Patients with this type of arthritis would seem to be good candidates for a shoulder replacement, but replacing the shoulder in the typical fashion has not been successful.

The “normal” artificial shoulder was designed to copy our real shoulder. The glenoid component (the socket) was designed to replace our normal shoulder socket with a thin, shallow plastic cup. The humeral head component was designed to replace the ball of the humerus with a metal ball that sits on top of the glenoid. This situation has been compared to placing a ball on a shallow saucer. Without something to hold it in place, the metal ball simply slides around on the saucer. In the shoulder that something is the rotator cuff and the muscles that attach to the tendons. Without a rotator cuff to hold the metal ball centered in the plastic socket, the metal quickly wore out the plastic socket and the joint became painful once again.

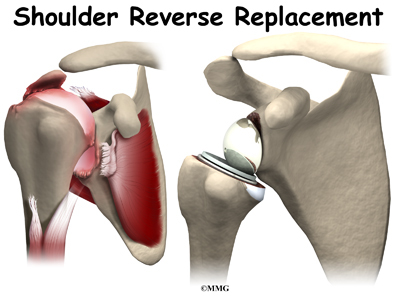

The answer to this dilemma was to rethink the mechanics of the shoulder joint and design an artificial shoulder that worked differently than the real shoulder joint. The solution was to reverse the socket and the ball, placing the ball portion of the shoulder where the socket use to be and the socket where the ball or humeral head use to be. This new design led to a much more stable shoulder joint that could function without a rotator cuff. The artificial joint itself provided more stability by creating a deeper socket that prevented the ball from sliding up and down as the shoulder was raised. The large deltoid muscle that covers the shoulder could be used to more effectively lift the arm, providing better function of the shoulder. The final result is a shoulder that functions better, is less painful and can last for years without loosening.

Other reasons to consider a reverse shoulder replacement include failed rotator cuff surgery leading to a pseudoparalytic shoulder even without arthritis. A pseudoparalytic shoulder refers to a situation where you can not raise the shoulder. Pseudo means false and paralysis usually means that the nerves that control the muscle no longer control the muscles. A pseudoparalytic shoulder appears paralyzed, but the reason that you cannot raise the shoulder is because the rotator cuff tendons that attach the muscles (that raise the shoulder) to the humerus bone are torn. The power of the muscles cannot be transmitted to the humerus to raise the shoulder.

Older patients with very severe fractures of the head of the humerus appear to do very well with reverse shoulder replacements as opposed to a standard shoulder replacement. Patients who have had previous shoulder replacements that have failed of become loose will also require a reverse shoulder replacement to fix the loose or painful prosthesis.

In most cases, doctors see a shoulder replacement as the last option. Sometimes there is a benefit to delaying shoulder replacement surgery as long as possible. Your doctor will probably want you to try nonsurgical measures to control your pain and improve your shoulder movement, including medications and physical or occupational therapy.

Like any arthritic condition, cuff tear arthropathy of the shoulder may respond to anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Acetaminophen (Tylenol ®) may also be prescribed to ease the pain. Some of the newer medications such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are more commonly prescribed today. They seem to be effective in helping reduce the pain of arthritis in all joints. There are also new injectable medications that lubricate the arthritic joint. These medications have been studied mainly in the knee. It is unclear if they will help the arthritic shoulder. These lubrication injections are presently being studied in the shoulder. Although they are safe in the knee, they are not presently approved for use in the shoulder.

Physical or occupational therapy may be suggested to help you regain as much of the motion and strength in your shoulder as possible before you undergo surgery. In many cases, however, therapy may not be indicated for severe shoulder arthritis since it may aggravate the pain. This is a matter to be discussed with your orthopedic surgeon.

An injection of cortisone into the shoulder joint may give temporary relief. Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication that can ease inflammation and reduce pain, possibly for several months. Most surgeons only allow two or three cortisone shots into any joint. If the shots don’t provide you with lasting relief, your doctor may suggest surgery.

Preparation

What do I need to do to get ready for surgery?

When cuff tear arthropathy of the shoulder requires replacement of the painful shoulder with an artificial shoulder joint, a reverse shoulder replacement may be recommended. You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

Special x-rays will be needed. Plain x-rays of the shoulder will allow your surgeon to evaluate the severity of arthritis and the status of the rotator cuff. A CT scan is always required before any kind of shoulder replacement to determine the degree of damage to the bones (glenoid and humeral head) for surgical planning.

You may also need to spend time with the physical or occupational therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this pre-operative visit is to record a baseline of information. Your therapist will check your current pain levels, ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each shoulder.

A second purpose of the pre-operative visit is to prepare you for surgery. You’ll begin learning some of the exercises you will use during your recovery. Your therapist can help you anticipate any special needs or problems you might have at home, once you’re released from the hospital.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before. Come prepared to stay in the hospital for several nights. The length of time you will spend in the hospital depends a lot on you.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during shoulder replacement surgery?

Before we describe the procedure, let’s look first at the reverse artificial shoulder itself.

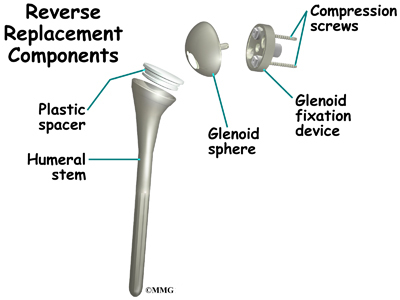

The Reverse Artificial Shoulder

The reverse shoulder prosthesis (artificial joint) is made up of two parts. The humeral component replaces the humeral head, or the ball of the joint. The glenoid component replaces the socket of the shoulder, which is actually part of the scapula.

In the “normal” artificial shoulder prosthesis, the glenoid prosthesis is a shallow socket made of plastic and the humeral component is a metal stem attached to a metal ball that nearly matches the anatomy of the normal shoulder. In the reverse shoulder replacement, the ball and the socket are reversed.

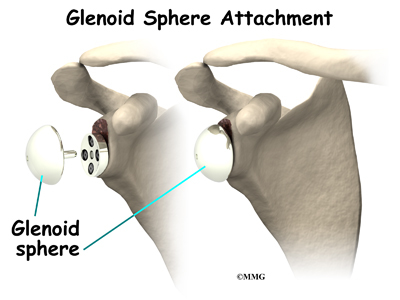

The humeral component is combination of a metal stem that fits into the marrow cavity of the upper humerus and, on top of the metal stem, a plastic socket. This plastic socket fits onto the humeral component to create a ball and socket type bearing. The glenoid component is usually made of two parts. A metal tray (base plate) attaches directly to the bone. The glenoid base plate is inserted into a small peg hole drilled into the bone and is secured with special screws through the base plate into the bone. Attached to that metal tray, a metal ball is attached that will fit into the plastic socket attached to the humeral component. The plastic is very tough and very slick, much like the articular cartilage it is replacing. In fact, you can ice skate on a sheet of this plastic without causing it much damage.

The Operation

The reverse shoulder replacement surgery is performed almost identically to the normal shoulder replacement – except different artificial parts are inserted.

You will most likely need general anesthesia for shoulder replacement surgery. General anesthesia puts you to sleep. It is difficult to numb only the shoulder and arm in a way that makes such a major surgery possible. While nerve blocks can be helpful with postoperative pain control, they are not usually effective enough to be used as the only anesthetic for this kind of operation.

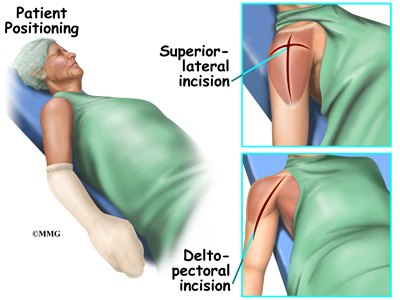

Shoulder replacement surgery is done through an incision on the front of your shoulder. This is called an anterior (deltopectoral) approach. For reverse shoulder replacements, especially for patients with multiple previous surgeries, a superior approach through the deltoid muscle may be used. The surgeon cuts through the skin and then isolates the nerves and blood vessels and moves them to the side. The muscles are also moved to the side.

The surgeon enters the shoulder joint itself by cutting into the joint capsule. This allows the surgeon to see the joint. In more advanced cases of cuff tear arthropathy, and in patients with previous surgery, there may be no capsule and rotator cuff remaining.

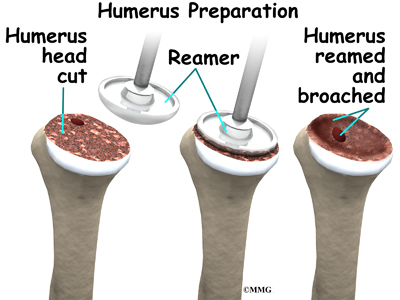

At this point, the surgeon can prepare the bone for attaching the replacement parts. The ball portion of the humeral head is removed with a bone saw. The hollow inside of the upper humerus is prepared using a rasp. This lets your surgeon mold the space to anchor the metal stem of the humeral component inside the bone.

View animation of drilling the humerus

View animation of removing the humeral head

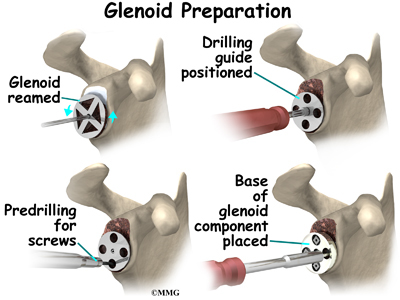

The glenoid will be replaced with a ball of metal. The arthritic glenoid surface is prepared by grinding away any remaining cartilage and flattening the surface. This is done with an instrument called a reamer. The surgeon usually uses the reamer to drill holes into the bone of the scapula and to flatten the deformed glenoid surface so the base plate rests on a smooth, flat surface. This is where the stem of the glenoid component is anchored.

View animation of reaming the glenoid

View animation of drilling the glenoid

View animation of

inserting the glenoid base plate

Finally, the humeral component and the glenoid component are inserted.

View animation of reaming the humerus

View animation of inserting the glenoid sphere

View animation of inserting the humerus implants

View animation of the completed implant

Once the joint is anchored, the surgeon tests for proper fit. When the surgeon is satisfied with the fit, the joint capsule is stitched together. The muscles are then returned to their correct positions, and the skin is also stitched up.

Your incision will be covered with a bandage, and your arm will be placed in a sling. You will then be woken up and taken to the recovery room.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following reverse artificial shoulder replacement are

- anesthesia

- infection

- fracture

- dislocation

- loosening

- nerve or blood vessel injury

Anesthesia

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Infection

Infection following reverse joint replacement surgery can be very serious. The chances of developing an infection following artificial joint replacement, however, are low (about one percent). Sometimes infections show up very early, before you leave the hospital. Other times infections may not show up for months, or even years, after the operation.

Infection can also spread into the artificial joint from other infected areas. Once an infection lodges in your joint, it is almost impossible for your immune system to clear it. You may need to take antibiotics when you have dental work or surgical procedures on your bladder and colon. The antibiotics reduce the risk of spreading germs to the artificial joint.

Fracture

During the surgery, the humerus is prepared by cutting off the deformed humeral head and reaming the canal to allow for insertion of the humeral stem. The glenoid is reamed to create a bone tunnel, and flattened to seat the glenoid base plate. In patients with weak bone, fractures can occur during this part of the procedure that may require restricted activity after the surgery while the fracture heals.

Dislocation

Just like your real shoulder, an artificial shoulder can dislocate. A shoulder dislocation occurs when the ball comes out of the socket. There is a greater risk of dislocation right after surgery, before the tissues have healed around the new joint. But there is always a slightly increased risk of dislocation with an artificial joint. Your therapist will teach you how to avoid activities and positions that tend to cause shoulder dislocation. A shoulder that dislocates more than once may need another operation to make it more stable.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Dislocations

Loosening

The major reason that artificial joints eventually fail is that they loosen where the metal or cement meets the bone. A loose joint prosthesis causes pain. Once the pain becomes unbearable, another operation will probably be needed to fix the artificial joint.

There have been great advances in extending the life of artificial joints. However, most will eventually loosen and require another surgery. In the case of artificial knees, you can expect about 12 to 15 years, but artificial shoulder joints tend to loosen sooner.

Nerve or Blood Vessel Injury

All of the large nerves and blood vessels to the arm and hand travel through the armpit. (This area is called the axilla.) Because shoulder replacement surgery takes place so close to the axilla, it is possible that the nerves or blood vessels may be injured during surgery. The resulting problems may be temporary if the injury was caused by stretching to hold the nerves out of the way. The nerves and blood vessels rarely suffer any kind of permanent injury after reverse shoulder replacement surgery, but this type of injury can happen.

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

After surgery, you’ll be transported to the recovery room. You will have a dressing wrapped over your shoulder that will need to be changed frequently over the next few days. Your surgeon may have inserted a small drainage tube into the shoulder joint to help keep extra blood and fluid from building up inside the joint. An intravenous line (IV) will be placed in your arm to give you needed antibiotics and medication.

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

A physical or occupational therapist will see you the day after surgery to begin your rehabilitation program. Therapy treatments will gradually improve the movement in your shoulder. Your therapist will go over your exercises and make sure you are safe getting in and out of bed and moving about in your room.

When you go home, you may get home therapy visits. By visiting your home, your therapist can check to see that you are safe getting around in your home. Treatments will also be done to help improve your range of motion and strength. In some cases, you may require up to three visits at home before beginning outpatient therapy. Out patient therapy at a facility can often more effective and is often preferred over home physical therapy.

The first few outpatient treatments will focus on controlling pain and swelling. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may help. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain. Continue to use your shoulder sling as prescribed.

As the rehabilitation program evolves, more challenging exercises are chosen to safely advance the shoulder’s strength and function.

Finally, a select group of exercises can be used to simulate day-to-day activities, like grooming your hair or getting dressed. Specific exercises may also be chosen to simulate work or hobby demands.

When your shoulder range of motion and strength have improved enough, you’ll be able to gradually get back to normal activities. Ideally, you’ll be able to do almost everything you did before. However, you may need to avoid heavy or repeated shoulder actions.

You may be involved in a progressive rehabilitation program for two to four months after surgery to ensure the best results from your artificial joint. In the first six weeks after surgery, you should expect to see your therapist two to three times a week. At that time, if everything is still going as planned, you may be able to advance to a home program. Then you will only check in with your therapist every few weeks.

Many patients with a reverse shoulder replacement will be able to lift the arm overhead with little or no pain. Some patients, however, may take many months to recover their range of motion. While these patients will usually have excellent pain relief, motion recovery may be very slow due to years of disuse and deconditioning of the deltoid muscle.

Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy

A Patient’s Guide to Rotator Cuff Tear Arthropathy

Introduction

The rotator cuff is a unique structure in the shoulder that is formed by four tendons. These four tendons attach to four muscles that help keep the shoulder stabilized in the socket (or glenoid) and help rotate the upper arm inward and outward. If the rotator cuff is torn and is not repaired, a type of wear and tear arthritis of the shoulder can develop over time. This condition is sometimes called arthropathy and the term cuff tear arthropathy is used to describe this type of arthritis of the shoulder that develops when the rotator cuff is damaged. If you develop this condition, your shoulder will be painful. Movement and strength of the shoulder will be decreased. Moving the arm away from the body and raising it over your head can be especially difficult.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the shoulder are involved

- what causes this condition

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the shoulder are involved?

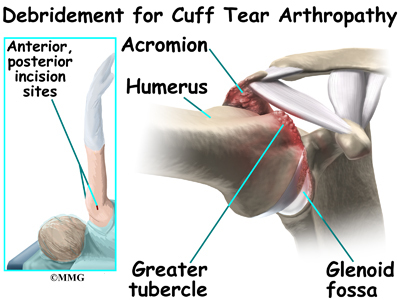

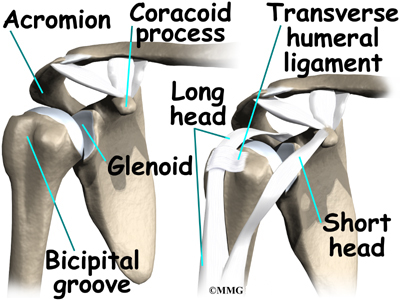

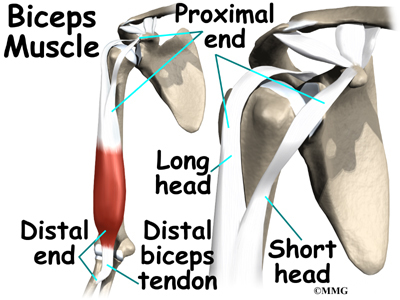

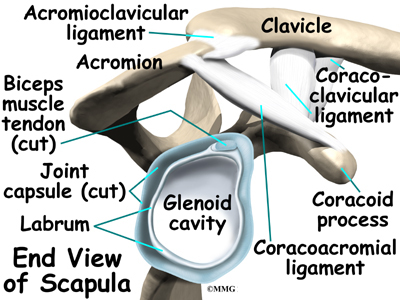

The bones of the shoulder are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the scapula (the shoulder blade), and the clavicle (the collar bone). The roof of the shoulder is formed by a part of the scapula called the acromion. The shoulder joint is also called the glenohumeral joint. One of the bones of the glenohumeral joint is the humerus (the long bone of the upper arm).

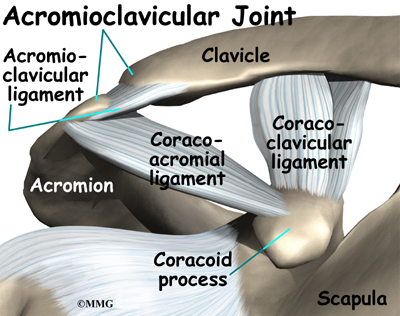

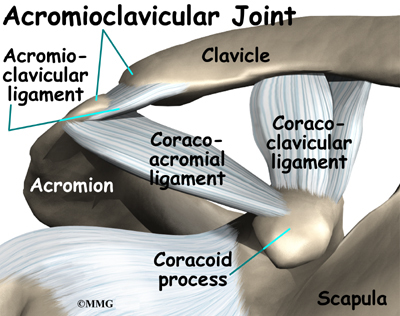

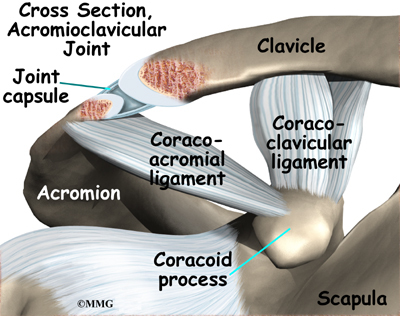

It has a ball, called the humeral head on the top end. The humeral head fits into a small, shallow cup called the glenoid fossa. It makes up the other part of the glenohumeral joint. The glenoid fossa is part of the shoulder blade. A large ligament runs from the front of the acromion to another part of the shoulder blade called the coracoid process. This ligament is called the coracoacromial ligament. It adds stability to the front of the shoulder.

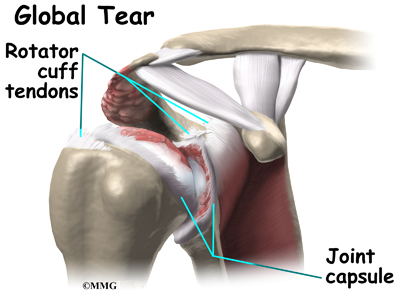

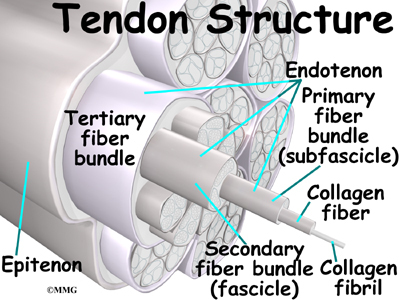

The rotator cuff is made up of tough, fibrous tissue. It forms a cuff (or capsule) covering the shoulder joint. There are four tendons that help form the rotator cuff. The muscles that form the tendons are the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. These muscles rotate the shoulder outward and inward. Along with another muscle, the deltoid, they also help lift the arm away from the body.

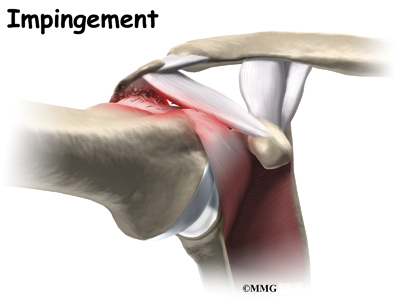

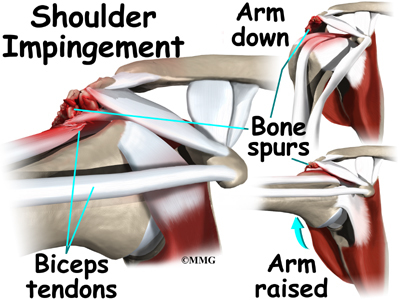

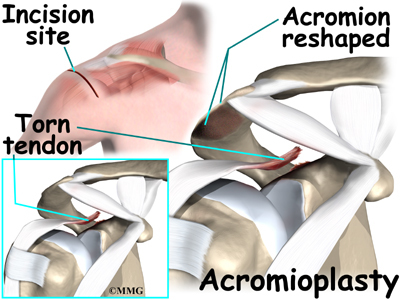

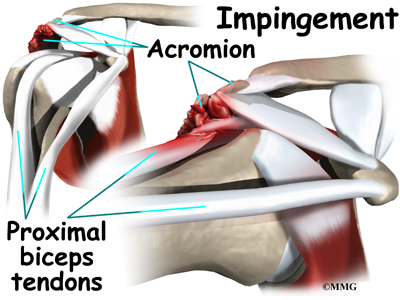

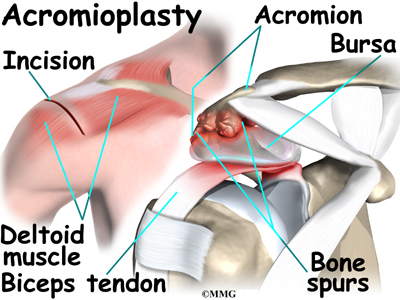

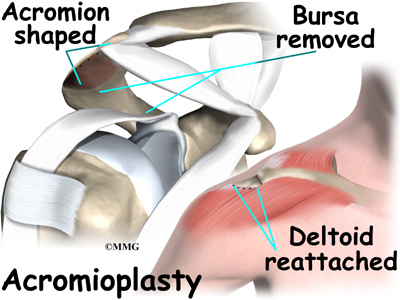

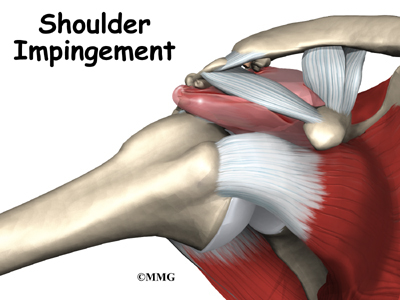

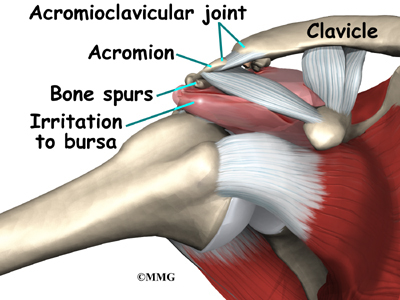

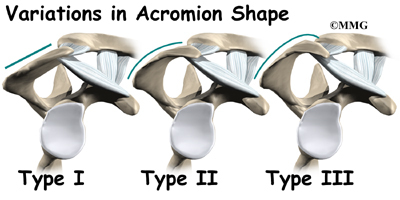

The rotator cuff slides between the humeral head and the acromion as we raise our arm. As this sliding occurs over and over, the rotator cuff tendons will often be pinched as you use the shoulder everyday. This pinching is called impingement. Over time this pinching can lead to damage and weakening of the rotator cuff tendons.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Rotator Cuff Tears

Causes

What causes this condition?

Dr. Charles Neer actually described rotator cuff tear arthropathy (RCTA) in 1977. Today, doctors generally refer to this as simply cuff tear arthropathy. Cuff tear arthropathy is actually a type of wear and tear, or degenerative arthritis of the shoulder that develops over time after the rotator cuff is damaged.

Normally, when the rotator cuff muscles contract, they pull the head of the humerus tightly into the socket of the shoulder. This stabilizes the shoulder and allows the the large deltoid muscle to raise the arm over the head as it rotates the humeral head like a pulley. This motion needs the rotator cuff and deltoid muscles to work together – in balance. When the rotator cuff is torn, the shoulder becomes unbalanced. The deltoid muscle pulls the head of the humerus up into the acromion in a sliding motion.

When the top of the humerus hits the underside of the acromion, the deltoid may be able to pull the arm part way up as it levers against the underside of the acromion. But, over time this abnormal sliding motion causes wear and tear on the joint surfaces. Arthritis develops and any motion becomes painful. The shoulder becomes weaker and weaker until you can no longer raise the arm above the head.

Rotator cuff tears are very common. Trauma, such as falls, lifting, and pulling forcefully can also cause a rotator cuff tear. When this happens, it is called an acute tear. Although the rotator cuff can be damaged from a single traumatic injury, damage to the rotator cuff usually occurs gradually. Age can be a factor. As we age, the tendons of the rotator cuff become weaker and more likely to be injured. The blood supply to the tendons diminishes with age. Rotator cuff tears are much more likely to occur after the age of 40.

Certain activities can increase the wear and tear on the rotator cuff. Repetitive overhead activity such as painting, plastering, racquetball, weightlifting, and swimming can cause wear and tear of the rotator cuff.

Surgeons generally will recommend surgery to repair a rotator cuff tear when it occurs. A successful surgical repair of a torn rotator cuff tear can make the development of cuff tear arthropathy much less likely. But, sometimes a rotator cuff tear cannot be repaired. The tissue is simply too damaged and cannot fixed. This is not an uncommon situation in older patients with rotator cuff tears.

In other cases, the patient simply elects not to have surgery to repair a rotator cuff tear and chooses to simply live with the discomfort. Over several years, both of these situations can result in the later development of rotator cuff arthropathy.

Symptoms

What does this condition feel like?

The most common symptom of rotator cuff tear arthropathy is pain in and around the shoulder. The pain can also radiate into your neck, arm, even into your wrist or hand. The shoulder can be especially painful when trying to lift the arm, or rotate it outward. The pain is usually worse at night. It can interrupt your sleep, especially if you try to sleep on the affected shoulder. If untreated, the pain can be nearly continuous and can be severe.

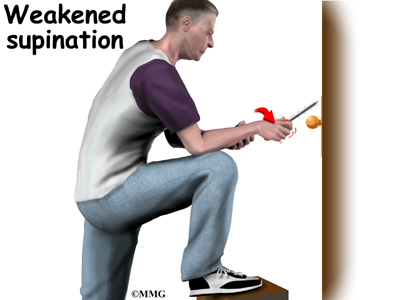

Weakness of the shoulder makes it difficult, if not impossible to lift the arm overhead. Often, even starting this motion can be difficult. The tendency is to shrug the shoulder in order to lift the arm part of the way. With time, weakness of the rotator cuff muscles will worsen. Range of motion can be quite limited. You will often find it difficult to do routine things, like reaching behind your back, reaching into a cabinet, or combing your hair. You may notice a crackling or popping sensation. When there is arthritis of the glenohumeral joint, there is often a creaking or grating sound.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose this condition?

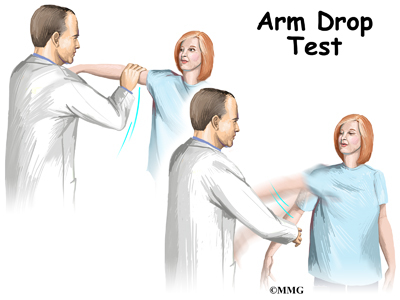

Your doctor will want to do a history and physical examination. He will ask you about activities or trauma that could have injured your shoulder. He will want to know the level of your pain, and what limitations you have. A physical examination is done. Range of motion and strength of the shoulder muscles will be evaluated. Your doctor will want to look at your shoulder to see if there is bony deformity, or atrophy (shrinkage) of the muscles. With a complete rotator cuff tear, moving the arm away from the body can be nearly impossible. If your doctor lifts your arm for you, and you cannot hold it up, this is called a positive Drop Arm Test. This usually means the rotator cuff is torn.

Other areas such as the neck may also need evaluation. A pinched nerve in the neck can mimic a rotator cuff tear. A neurological examination to include checking reflexes and sensation may be included. Your doctor may want you to have an electromyogram (EMG). This checks the function of the muscles of the shoulder. An EMG uses a small needle in the muscle being tested. It measures the electrical activity of the muscle at rest, and when tightened.

Your doctor will request X-rays of your shoulder. X-rays show the shape of the bones and joints. When the rotator cuff is torn, the shoulder will often ride high, meaning that it sits higher in the joint than it should. It can also show how much damage ahs occurred to the joint surfaces.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows your doctor to look at slices of the area in question. The MRI machine uses magnetic waves, not X-rays to show the muscle, tendons, and ligaments of the shoulder. MRIs will show tears of the rotator cuff tendons. Atrophy of the muscles can also be evaluated with MRI. A computerized tomography (CT) scan shows slices of bone. Like X-rays, it uses radiation. A CT scan can help to more accurately determine the degree of damage of the glenohumeral joint. A CT scan is especially useful to plan surgery if an artificial shoulder replacement is considered for treatment.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Conservative care that includes physical therapy, ice, heat, and anti-inflammatories is tried first. The goal of treatment is to reduce pain, and increase range of motion and function. Corticosteroid injection into the shoulder joint is also sometimes helpful. Steroids are very powerful anti-inflammatory medications that can reduce pain temporarily. These injections will not heal the tear but may give pain relief for several weeks to months. If arthritis of the shoulder is advanced, and pain is continuous and severe, surgery may be the best option available.

Surgery

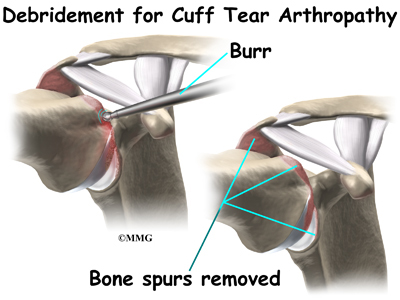

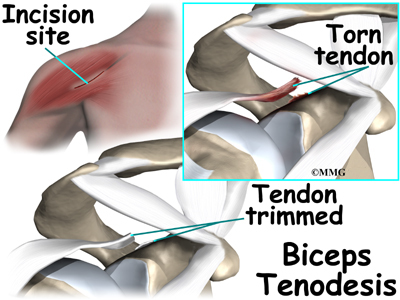

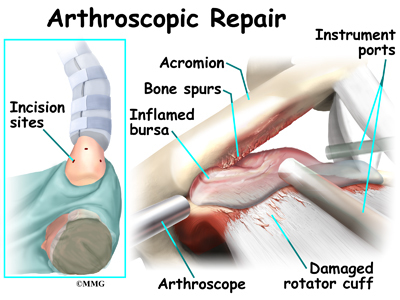

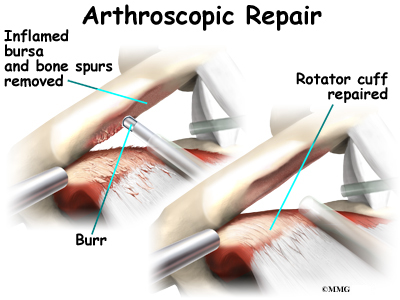

Cuff tear arthropathy is the result of long standing lack of rotator cuff function. In almost all cases, repair of the rotator cuff tear is no longer an option. Surgery for cuff tear arthropathy is done when pain and decreased motion continue after conservative care. The simplest surgical procedure to try and improve the situation is a debridement. During a debridement,

the surgeon will surgically remove (debride) any inflammed tissue, bones spurs and loose flaps of tendon tissue that may be catching in the joint and causing pain. This procedure may reduce pain, however, it does not always improve range of motion, strength, or function of the shoulder.

Patients with this type of arthritis would seem to be good candidates for a shoulder replacement, but replacing the shoulder in the typical fashion has not been successful. Replacing the shoulder with a special type of artficial shoulder joint is becoming more popular. This procedure is called a reverse shoulder replacement.

The “normal” artificial shoulder was designed to copy our real shoulder. The glenoid component (the socket) was designed to replace our normal shoulder socket with a thin, shallow plastic cup. The humeral head component was designed to replace the ball of the humerus with a metal ball that sits on top of the glenoid. This situation has been compared to placing a ball on a shallow saucer. Without something to hold it in place, the metal ball simply slides around on the saucer. In the shoulder that something is the rotator cuff and the muscles that attach to the tendons. Without a rotator cuff to hold the metal ball centered in the plastic socket, the metal quickly wore out the plastic socket and the joint became painful once again.

The answer to this dilemma was to rethink the mechanics of the shoulder joint and design an artificial shoulder that worked differently than the real shoulder joint. The solution was to reverse the socket and the ball, placing the ball portion of the shoulder where the socket use to be and the socket where the ball or humeral head use to be. This new design led to a much more stable shoulder joint that could function without a rotator cuff. The artificial joint itself provided more stability by creating a deeper socket that prevented the ball from sliding up and down as the shoulder was raised. The large deltoid muscle that covers the shoulder could be used to more effectively lift the arm, providing better function of the shoulder. The final result is a shoulder that functions better, is less painful and can last for years without loosening.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Your physical therapist will show you how to use ice or heat to help with pain. You will also be instructed in exercises to strengthen your shoulder girdle as much as possible. Showing you joint protection tips, or motion that you can expect to do safely without causing more harm to your shoulder is also important. The goal is to reduce pain, increase range of motion and function, and prevent further arthritis.

After Surgery

A physical or occupational therapist will see you the day after surgery to begin your rehabilitation program. Therapy treatments will gradually improve the movement in your shoulder. Your therapist will go over your exercises and make sure you are safe getting in and out of bed and moving about in your room.

When you go home, you may get home therapy visits. By visiting your home, your therapist can check to see that you are safe getting around in your home. Treatments will also be done to help improve your range of motion and strength. In some cases, you may require up to three visits at home before beginning outpatient therapy.

Out patient therapy at a facility can often more effective and is often preferred over home physical therapy. The first few outpatient treatments will focus on controlling pain and swelling. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may help. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain. Continue to use your shoulder sling as prescribed.

As the rehabilitation program evolves, more challenging exercises are chosen to safely advance the shoulder’s strength and function. Finally, a select group of exercises can be used to simulate day-to-day activities, like grooming your hair or getting dressed.

Weightlifter’s Shoulder

A Patient’s Guide to Weightlifter’s Shoulder (Distal Clavicular Osteolysis)

Introduction

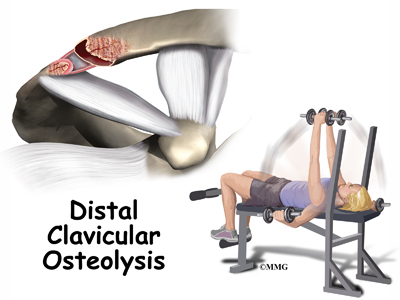

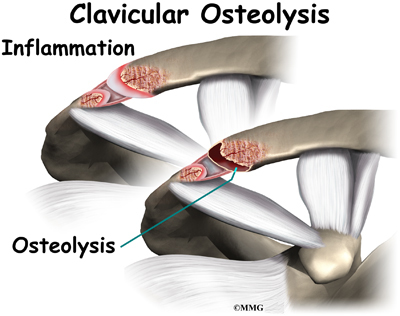

Weightlifter’s shoulder is a painful deterioration of the distal end of the clavicle (collar bone). It is an overuse phenomenon that causes tiny fractures along the end of the clavicle. A breakdown of the bone (osteolysis) occurs.

Weightlifters aren’t the only ones affected. Female bodybuilders, air-hammer operators, soldiers, handball players, and others can develop this problem. For that reason, it is also known as distal clavicular osteolysis (DCO). Osteolysis refers to the resorption of bone at the site of the injury.

This guide will help you understand

- how the problem develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the shoulder are affected?

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone).

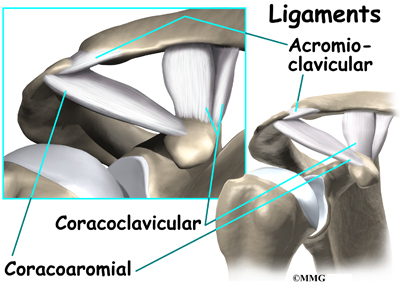

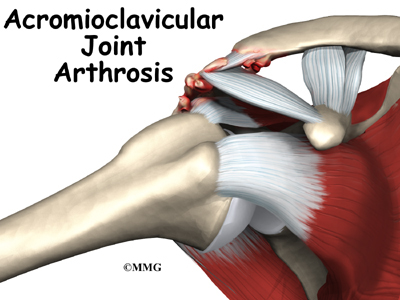

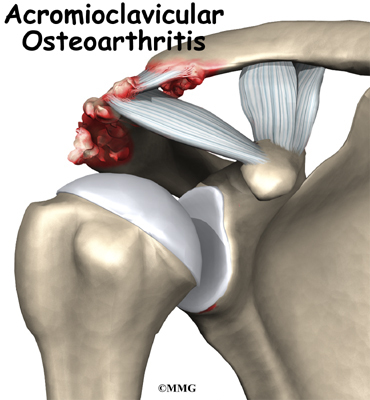

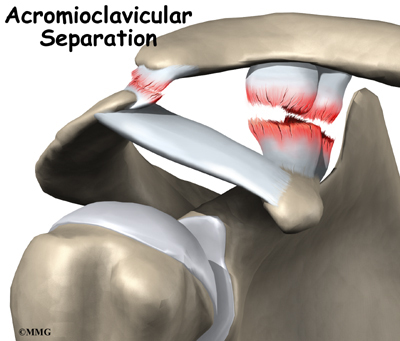

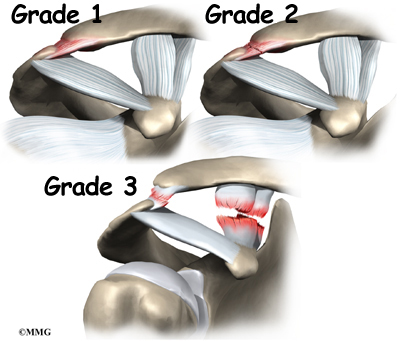

The acromioclavicular (AC) joint is affected most often. This is where the end of the collarbone (closest to the shoulder) attaches to the acromion. The acromion is a curved piece of bone that comes from the shoulder blade across the top of the shoulder. The clavicle and acromion meet to form the AC joint in front of the shoulder.

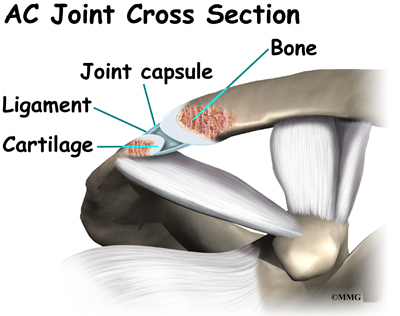

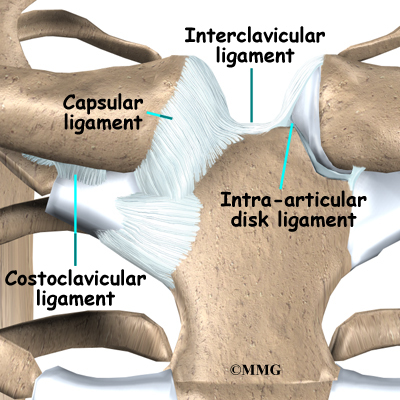

Ligaments and soft tissues hold the AC joint together and provide stability. These include the coracoclavicular ligament, superior and inferior AC ligaments, and the AC joint capsule. There is also a fibrocartilaginous disc between the clavicle and acromion to provide cushion and help transmit and offload forces on the joint.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Cause

What causes this condition?

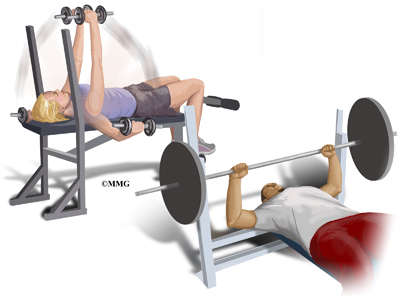

Repetitive trauma or stress from training and lifting causes tiny fractures of the distal end of the clavicular bone. Excessive traction on the AC joint from bench presses or chest fly exercises occurs when the elbows drop below or behind the body. This places the shoulders in a position of excess extension. Because the bone doesn’t have a chance to heal before the next training session begins, the bone actually starts to dissolve.

There may be a history of an acute injury of the AC joint. But the condition can occur without any known trauma. In most cases, there is repetitive stress to the affected upper extremity. Weight training, intensive lifting, and operating an air hammer are examples of the activities leading to acute distal clavicular osteolysis.

There is evidence that the body tries to heal itself but the bone dissolves or is resorbed by the body instead. A network of blood vessels forms in the area during the attempted healing process. Chronic inflammation with scar tissue called fibrosis is commonly found when tissue from the area is examined under a microscope.

The synovial lining of the joint starts to overproduce itself. Invasion of the underlying bone begins. Degenerative joint disease occurs as an end-result of the pathologic process.

Symptoms

What are the symptoms?

You feel an aching pain in the front of the shoulder at the AC joint. Pressing on the AC joint causes increased pain and tenderness. There is often weakness associated with the degenerative bone changes. For the weightlifter, symptoms are the most severe the night after a weightlifting competition or program.

Moving the arm across the body hurts. It gets worse with weight training involving the upper extremities (arms). Activities such as push-ups, bench presses, power clean exercises, dips on the parallel bars, and throwing motions make the symptoms worse. . Lying on the affected side can disrupt sleep.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

The history and physical examination are probably the most important tools the physician uses to diagnose. Your doctor may move and feel your sore joint. This may hurt, but it is very important that your doctor understand exactly where your joint hurts and what movements cause you pain.

The diagnosis is made using X-rays, scintigraphy (bone scan), and steroid injection. CT-guided injection is actually a diagnostic tool and a treatment. Pain relief with steroid injection into the AC joint confirms that the pain is coming from the AC joint.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment begins with conservative (nonoperative) care. This may include rest and/or changes in weight-training activities and techniques. Avoiding over-training and smoking are two very effective ways to prevent this condition. If it does develop, take quick steps to modify weightlifting techniques and avoid over-training.

A weight-trainer or physical therapist can help you with activity modification and specific strength training for this problem. For example, you can narrow your hand spacing on the barbells. This takes the stress off the distal clavicle. End your bench presses two inches above the chest. Some lifters place a two-inch folded towel on the chest as a reminder.

The power clean or power jerk can also be modified. Don’t rack the bar. Start with the elbows even with or above the shoulders and lift. This eliminates the power pull. Certain activities such as the bench press, dips, and push-ups should be avoided for a while. Apply an ice massage and take ibuprofen after each workout or exercise session.

Athletes must be careful to follow all recommendations for program modifications. There is a tendency to work through the pain and not really modify the program.

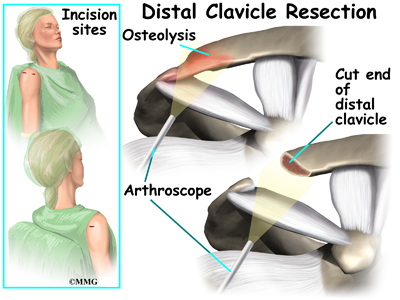

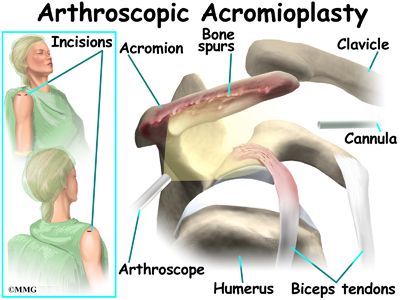

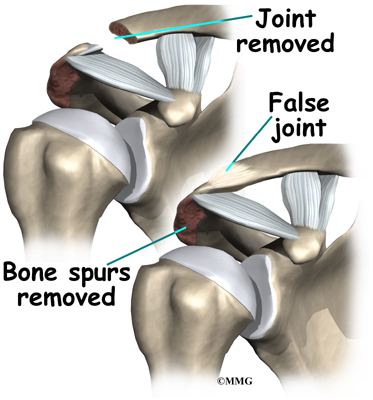

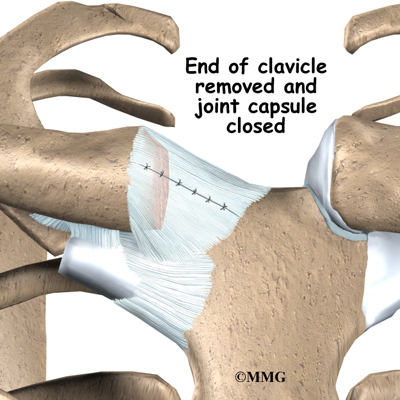

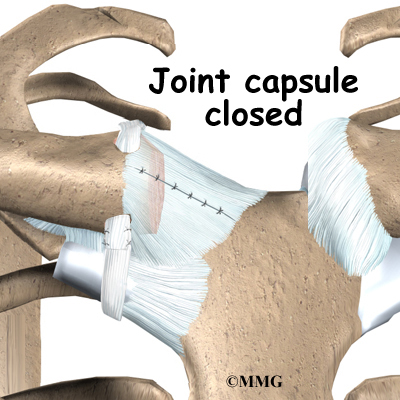

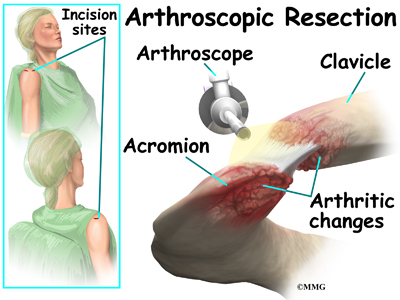

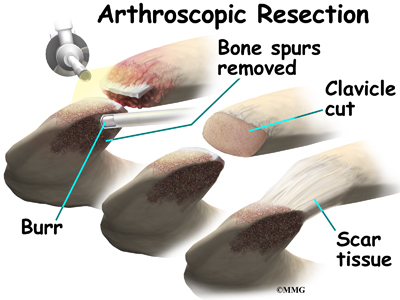

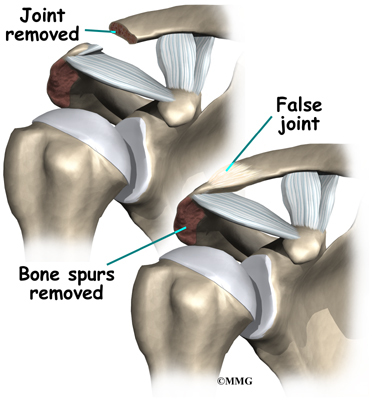

Surgery

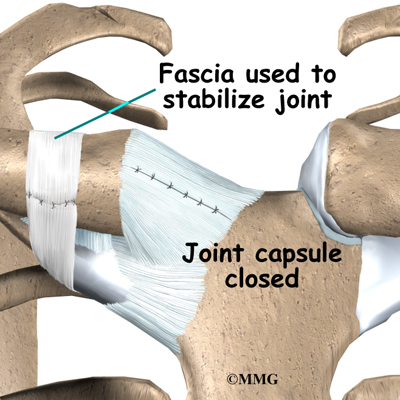

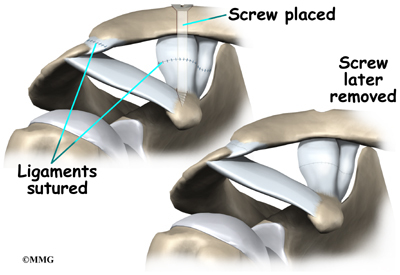

Surgery may be needed for those athletes who do not improve with conservative care or who are unwilling to change the training or performance routine. The surgeon removes the end of the clavicle. This is called a distal clavicle resection. The procedure can be done with an open incision or through tiny puncture holes with an arthroscope.

Repair of any torn soft tissue in the area is done at the same time. Some surgeons transfer the coracoacromial ligament over the end of the bone that has been cut. This helps stabilize the joint.

It’s possible to modify the procedure just a bit to stabilize the joint for a quick return-to-sport. The coracoacromial ligament can be transferred over the end of the bone that has been cut. This helps protect and stabilize the joint. It makes power lifting more comfortable for many athletes.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

You may experience a gradual lessening of painful symptoms until you are pain free. The therapist will help you gradually resume all activities without bringing back the problem.

For athletes who progress through the pain without activity modification, they may perform surgery on themselves. In this form of self-surgery, the clavicle will resect on its own. However, there may be an inflammatory response with increased symptoms setting you back in your program.

After Surgery

Many experienced weightlifters are able to continue training carefully. They can resume their program as early as three days after surgery. Most are back in full swing by the end of a week.

Pain is relieved in a majority of patients. Weightlifters are pleased that without the pain, they can quickly get back to their pre-operative level of lifting within a week or two. In fact, some even report exceeding their training weight once the pain is gone. Likewise, there are reports of manual laborers returning to full work duties. The turn around time is very short.

Patients should be warned that there could be some problems. Abnormal motion of the AC joint can lead to a poor result. In such cases, pain is not relieved. There can be muscle injury, prolonged bleeding, infection, and fracture of the clavicle during the procedure. Smokers are at greater risk of poor wound healing and failed surgery.

Shoulder Arthroscopy

A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Arthroscopy

Introduction

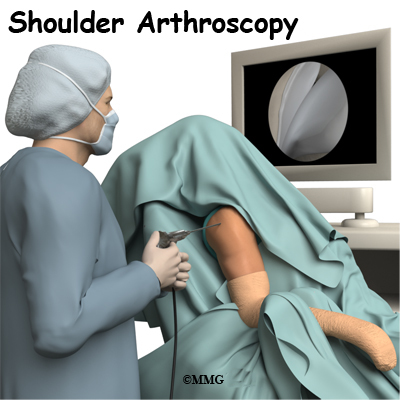

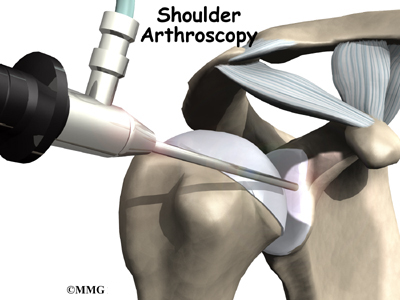

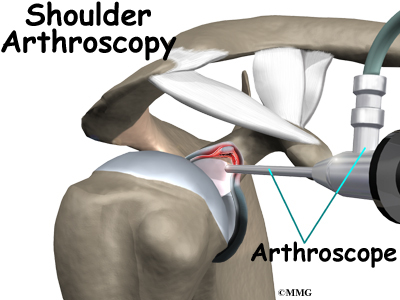

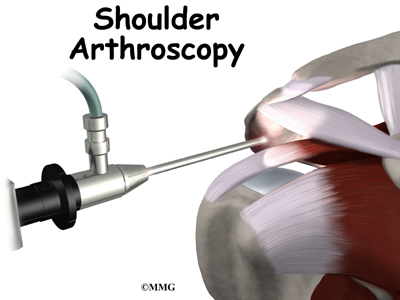

The use of arthroscopy (arthro means joint and scopy means look) has revolutionized many different types of orthopedic surgery. During a shoulder arthroscopy, a small video camera attached to a fiber-optic lens is inserted into the shoulder joint to allow a surgeon to see without making a large incision. Today the shoulder is one of the joints in which the arthroscope is commonly used to both diagnose problems and to perform surgical procedures inside the joint.

This guide will help you understand

- how the condition develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

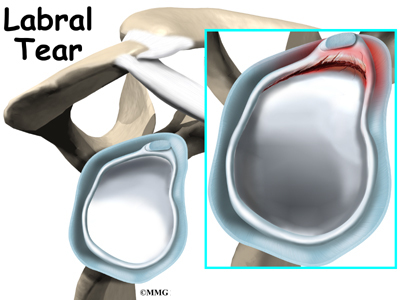

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone). A part of the scapula, called the glenoid, forms the socket of the shoulder. The glenoid is very shallow and flat, shaped somewhat like a dinner plate rather than a bowl. The humeral head forms the ball portion of the joint. Both the glenoid and the humeral head are covered with articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is the smooth, white material that covers the ends of bones in most joints. Articular cartilage provides a slick, rubbery surface that allows the bones to glide over each other as they move. Articular cartilage also functions as a shock absorber.

The rotator cuff connects the humerus to the scapula. The rotator cuff is formed by the tendons of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis. Tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move the bones by pulling on the tendons. The rotator cuff helps raise and rotate the arm. As the arm is raised, the rotator cuff also keeps the humerus tightly in the shoulder socket, the glenoid. The upper part of the scapula that makes up the roof of the shoulder is called the acromion.

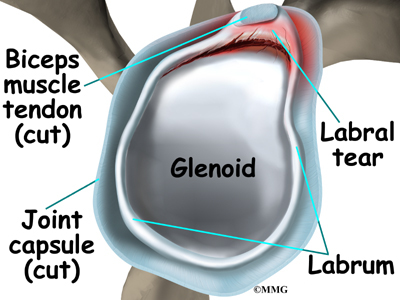

The shoulder joint is surrounded by a water tight pocket called the joint capsule. This capsule is formed by the rotator cuff tendons, ligaments, connective tissue and synovial tissue. When the joint capsule is filled with sterile saline and is distended, the surgeon can insert the arthroscope into the pocket that is formed, turn on the lights and the camera and see inside the shoulder joint as if looking into an aquarium. The surgeon can see nearly everything that is inside the shoulder joint including: (1) the joint surfaces of the glenoid socket and the humeral head (2) the rotator cuff tendons, (3) the glenoid labrum and (4) the synovial lining of the joint.

The arthroscope can also be placed in the space outside the shoulder joint known as the subacromial bursa. This bursa is a water tight pocket that sits above the shoulder joint. By placing the arthroscope into this space, the surgeon can see the underside of the distal end of the clavicle (collarbone) and the acromion as well as the joint that is formed where the clavicle and acromion meet, the acromioclavicular (AC) joint.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Rationale

What does my surgeon hope to accomplish??

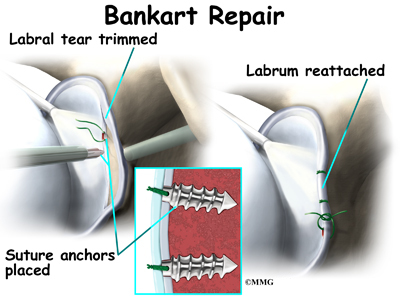

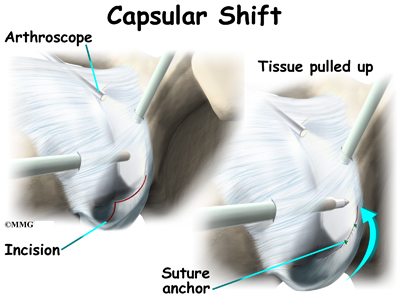

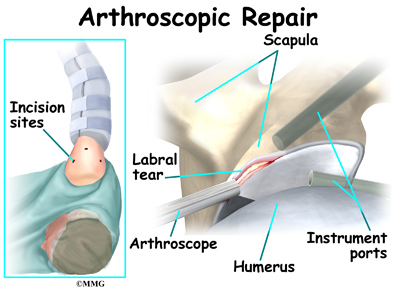

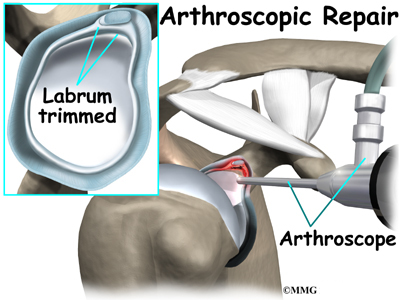

When shoulder arthroscopy first became widely available, it was used primarily to look inside the shoulder joint and make a diagnosis. Today, shoulder arthroscopy is used in performing a wide range of different types of surgical procedures on the shoulder joint including confirming a diagnosis, removing loose bodies, removing or repairing a torn labrum, reconstructing torn ligaments to prevent recurrent dislocation, repairing torn rotator cuff tendons and washing out debris from a shoulder that has become infected. Surgery can also be performed outside the joint in the subacromial bursa including removing bone spurs from the acromion and reconstructing an arthritic acromioclavicular joint.

Your surgeon’s goal is to fix or improve your problem by performing a suitable surgical procedure; the arthroscope is a tool that improves the surgeons ability to perform that procedure. The arthroscope image is magnified and allows the surgeon to see better and clearer. The arthroscope allows the surgeon to see and perform surgery using much smaller incisions. This results in less tissue damage to normal tissue and can shorten the healing process. But remember, the arthroscope is only a tool. The results that you can expect from a shoulder arthroscopy depend on what is wrong with your shoulder, what can be done inside your shoulder to improve the problem and your effort at rehabilitation after the surgery.

Preparations

What do I need to know before surgery?

You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, be sure and talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this preoperative visit is to record a baseline of information. The therapist will check your current pain levels, ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each shoulder.

A second purpose of the preoperative visit is to prepare you for surgery. The therapist will teach you the exercises you’ll use during your recovery.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted for surgery early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during shoulder arthroscopy?

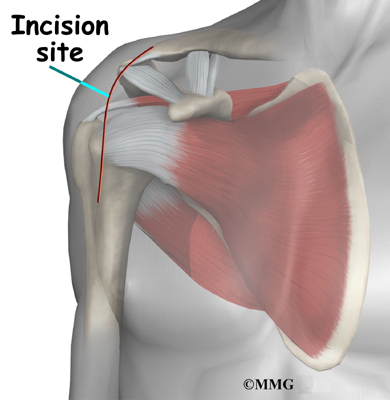

Before surgery you will be placed under either general anesthesia or a type of regional anesthesia. In simple cases, local anesthesia may be adequate. Sterile drapes are placed to create a sterile environment for the surgeon to work. There is a great deal of equipment that surrounds the operating table including the TV screens, cameras, light sources and surgical instruments.

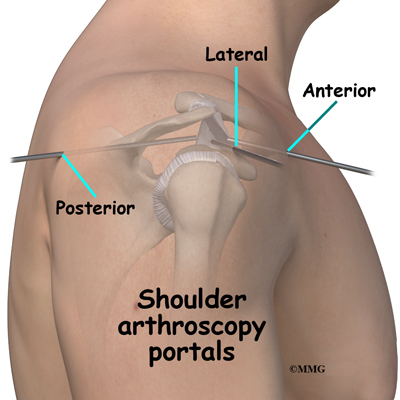

The surgeon begins the operation by making two or three small openings into the shoulder, called portals. These portals are where the arthroscope and surgical instruments are placed inside the shoulder joint. Care is taken to protect the nearby nerves and blood vessels. A small metal or plastic tube (or cannula) will be placed through one of the portals to inflate the shoulder joint with sterile saline.

The arthroscope is a small fiber-optic tube that is used to see and operate inside the joint. The arthroscope is a small metal tube about 1/4 inch in diameter (slightly smaller than a pencil) and about seven inches in length. The fiber-optics inside the metal tube of the arthroscope allows a bright light and TV camera to be connected to the outer end of the arthroscope. The light shines through the fiber-optic tube and into the shoulder joint. A TV camera is attached to the lens on the outer end of the arthroscope.

The TV camera projects the image from inside the shoulder joint on a TV screen next to the surgeon. The surgeon actually watches the TV screen (not the shoulder) while moving the arthroscope to different places inside the shoulder joint.