Artificial Knee Replacement (Knee Arthroplasty) Animated Tutorial

Knee

Knee Anatomy Animated Tutorial

Knee Anatomy

A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Introduction

To better understand how knee problems occur, it is important to understand some of the anatomy of the knee joint and how the parts of the knee work together to maintain normal function.

First, we will define some common anatomic terms as they relate to the knee. This will make it clearer as we talk about the structures later.

Many parts of the body have duplicates. So it is common to describe parts of the body using terms that define where the part is in relation to an imaginary line drawn through the middle of the body. For example, medial means closer to the midline. So the medial side of the knee is the side that is closest to the other knee. The lateral side of the knee is the side that is away from the other knee. Structures on the medial side usually have medial as part of their name, such as the medial meniscus. The term anterior refers to the front of the knee, while the term posterior refers to the back of the knee. So the anterior cruciate ligament is in front of the posterior cruciate ligament.

In addition to reading this article, be sure to watch our Knee Anatomy Animated Tutorial Video.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the knee

- how the parts of the knee work

Important Structures

The important parts of the knee include

- bones and joints

- ligaments and tendons

- muscles

- nerves

- blood vessels

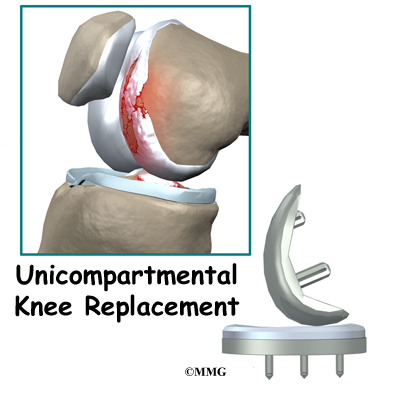

Bones and Joints

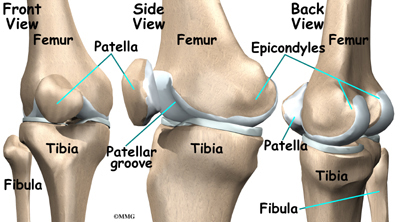

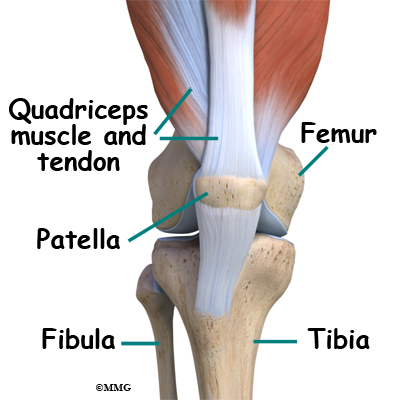

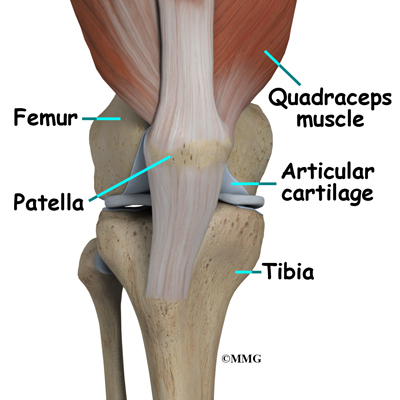

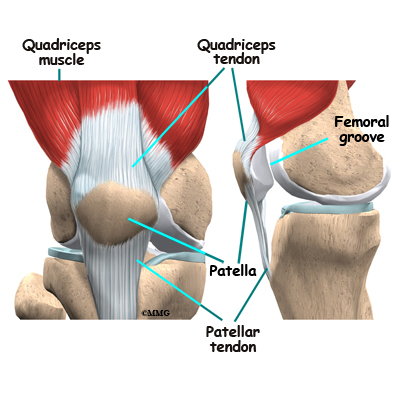

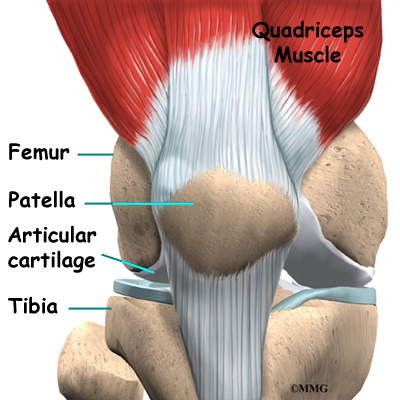

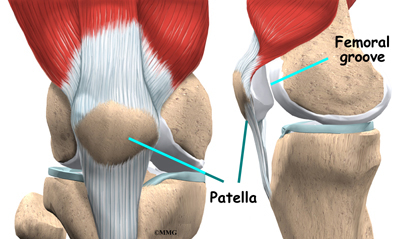

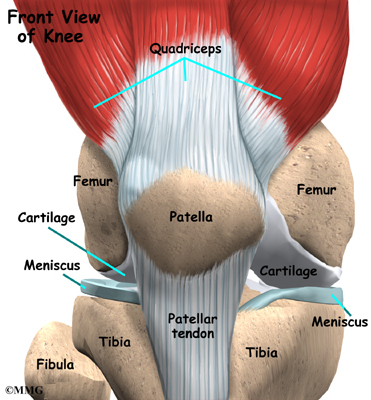

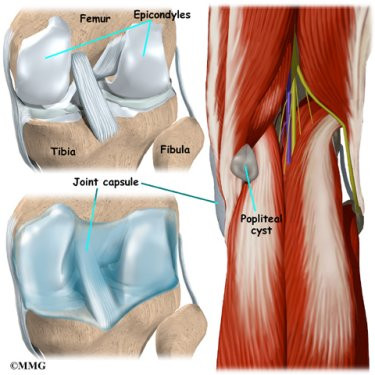

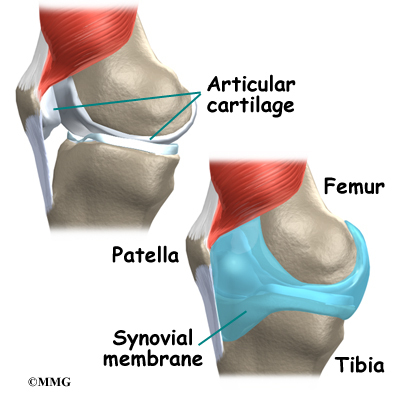

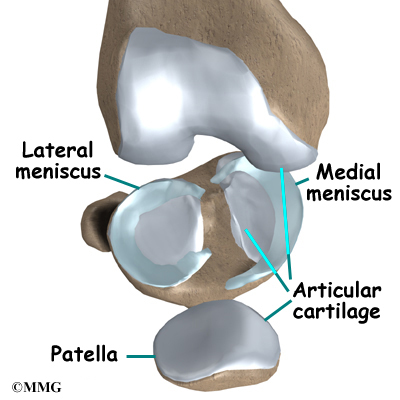

The knee is the meeting place of two important bones in the leg, the femur (the thighbone) and the tibia (the shinbone). The patella (or kneecap, as it is commonly called) is made of bone and sits in front of the knee.

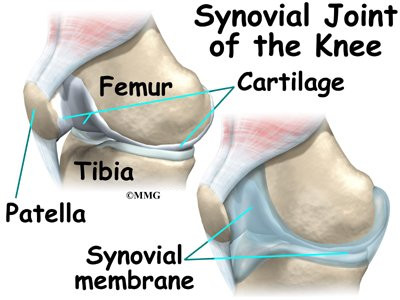

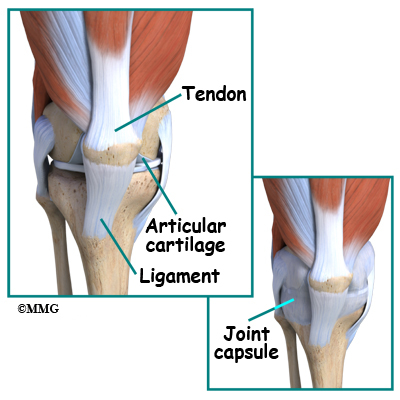

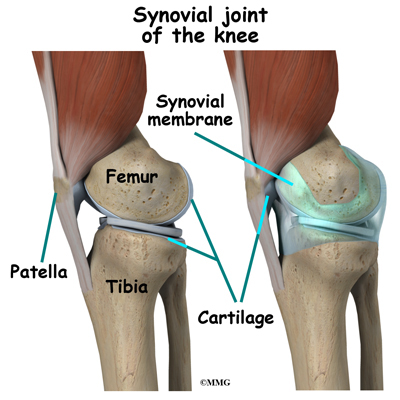

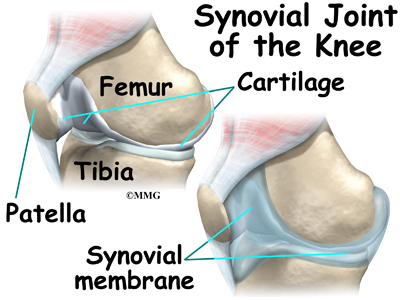

The knee joint is a synovial joint. Synovial joints are enclosed by a ligament capsule and contain a fluid, called synovial fluid, that lubricates the joint.

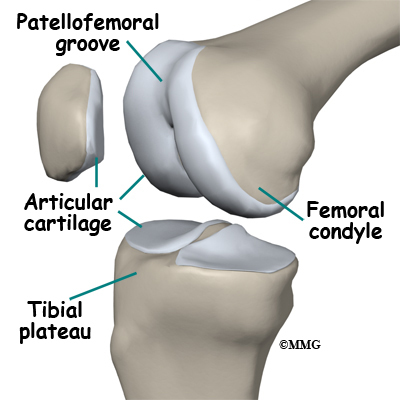

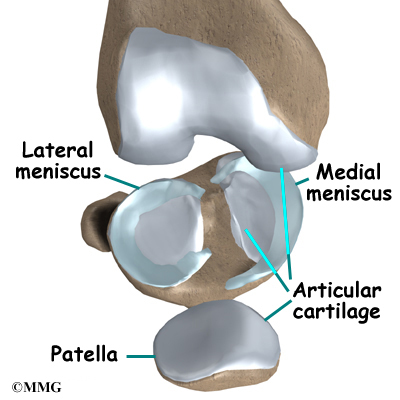

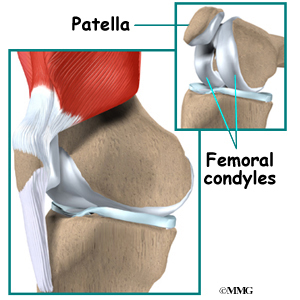

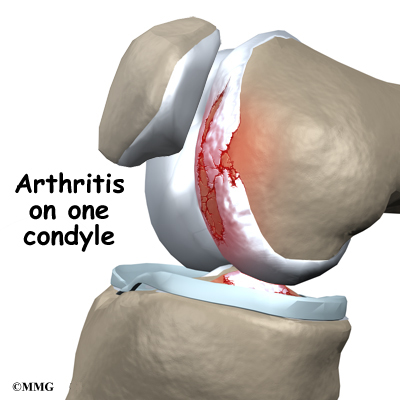

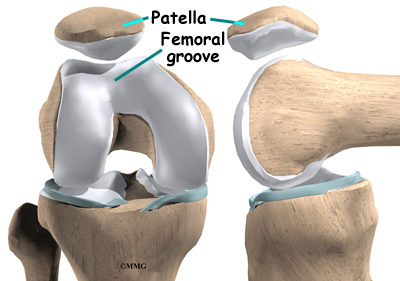

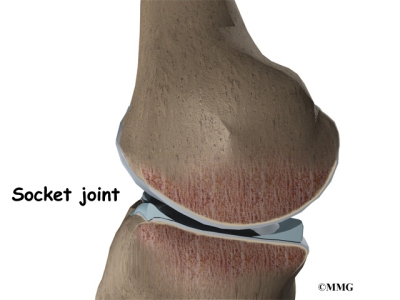

The end of the femur joins the top of the tibia to create the knee joint. Two round knobs called femoral condyles are found on the end of the femur. These condyles rest on the top surface of the tibia. This surface is called the tibial plateau. The outside half (farthest away from the other knee) is called the lateral tibial plateau, and the inside half (closest to the other knee) is called the medial tibial plateau.

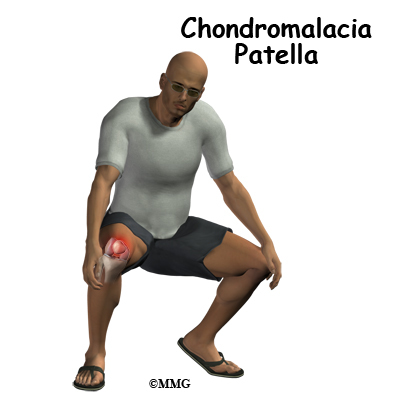

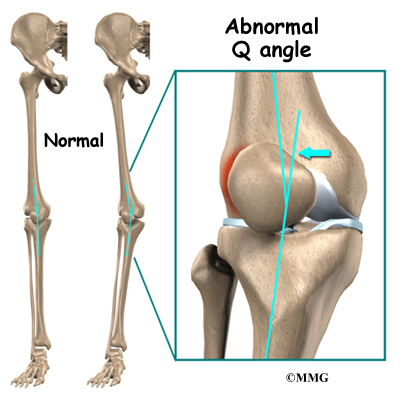

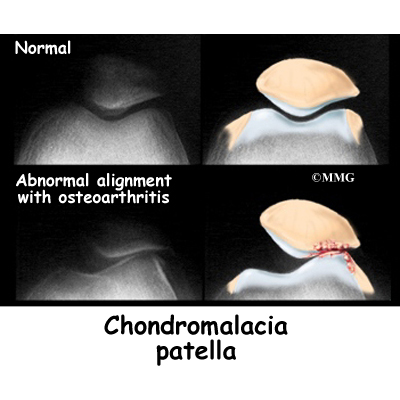

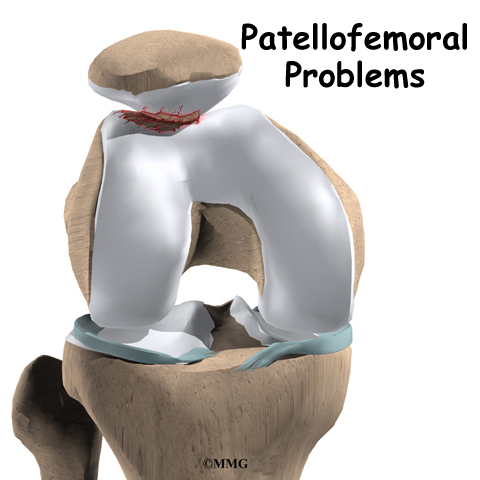

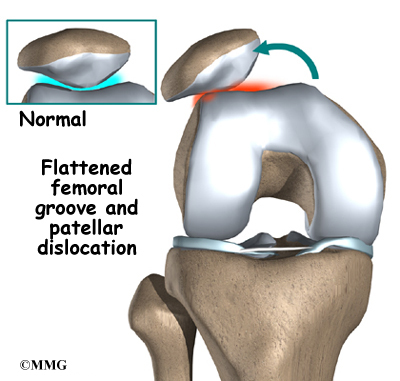

The patella glides through a special groove formed by the two femoral condyles called the patellofemoral groove.

The smaller bone of the lower leg, the fibula, never really enters the knee joint. It does have a small joint that connects it to the side of the tibia. This joint normally moves very little.

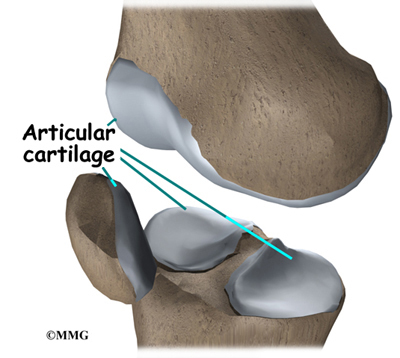

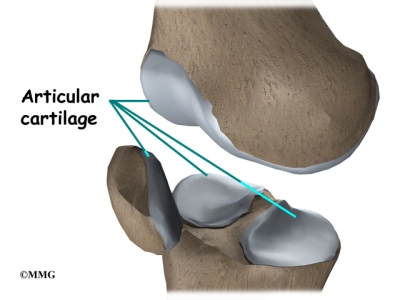

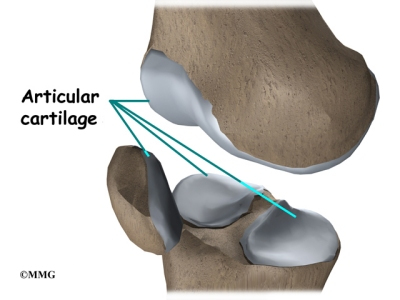

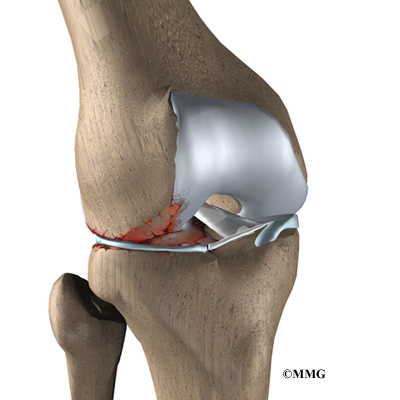

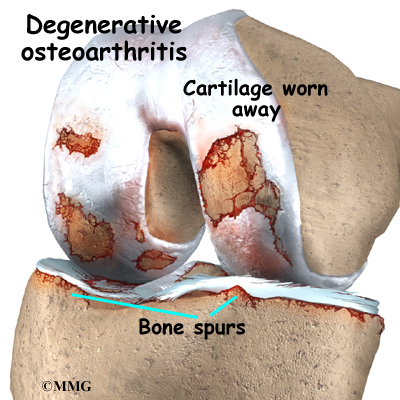

Articular cartilage is the material that covers the ends of the bones of any joint. This material is about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large joints. It is white and shiny with a rubbery consistency. Articular cartilage is a slippery substance that allows the surfaces to slide against one another without damage to either surface. The function of articular cartilage is to absorb shock and provide an extremely smooth surface to facilitate motion. We have articular cartilage essentially everywhere that two bony surfaces move against one another, or articulate. In the knee, articular cartilage covers the ends of the femur, the top of the tibia, and the back of the patella.

Ligaments and Tendons

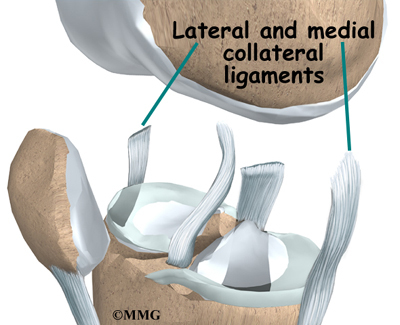

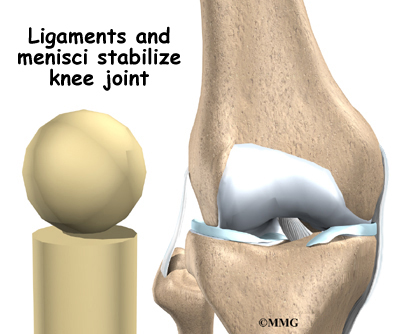

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect the ends of bones together. Two important ligaments are found on either side of the knee joint. They are the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and the lateral collateral ligament (LCL).

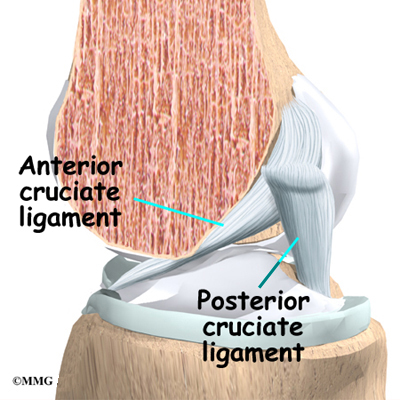

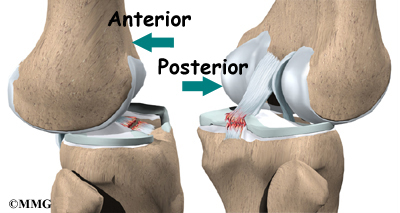

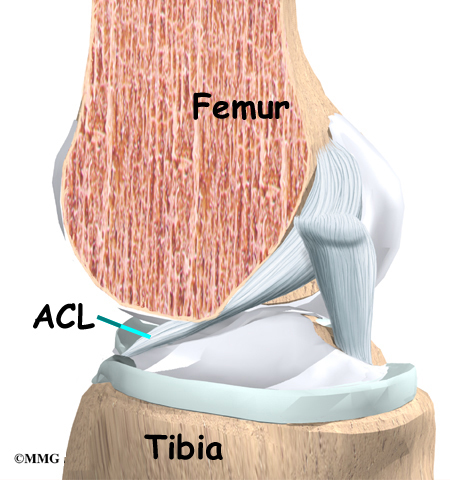

Inside the knee joint, two other important ligaments stretch between the femur and the tibia: the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in front, and the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) in back. The MCL and LCL prevent the knee from moving too far in the side-to-side direction. The ACL and PCL control the front-to-back motion of the knee joint.

The ACL keeps the tibia from sliding too far forward in relation to the femur. The PCL keeps the tibia from sliding too far backward in relation to the femur. Working together, the two cruciate ligaments control the back-and-forth motion of the knee. The ligaments, all taken together, are the most important structures controlling stability of the knee.

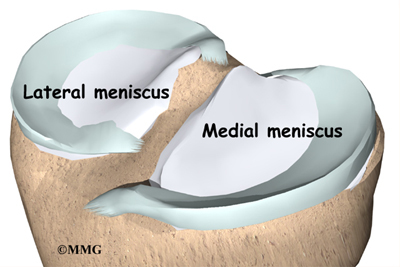

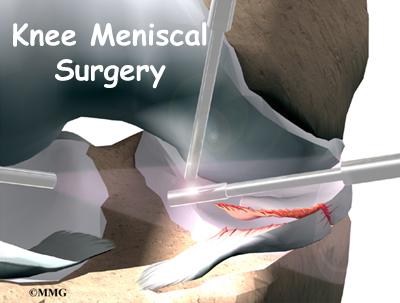

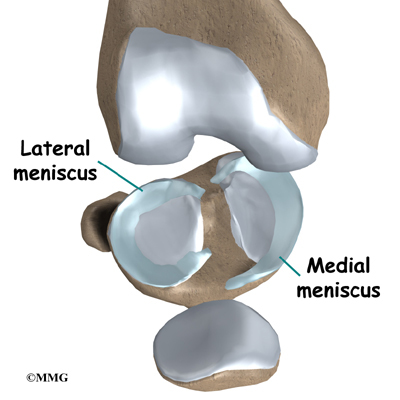

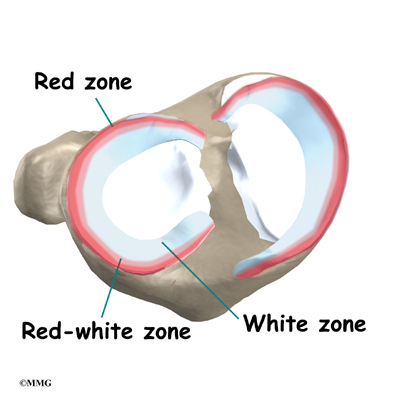

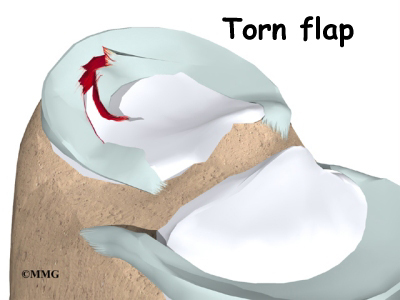

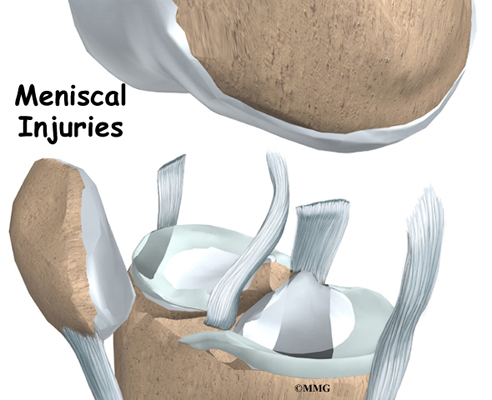

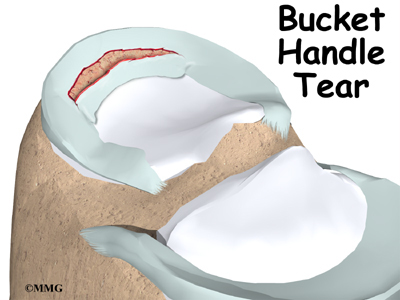

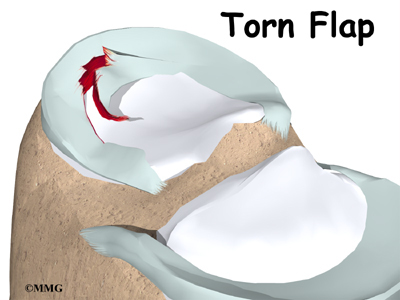

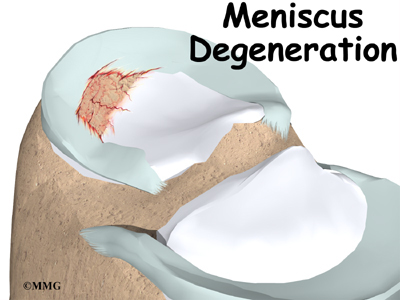

Two special types of ligaments called menisci sit between the femur and the tibia. These structures are sometimes referred to as the cartilage of the knee, but the menisci differ from the articular cartilage that covers the surface of the joint.

The two menisci of the knee are important for two reasons: (1) they work like a gasket to spread the force from the weight of the body over a larger area, and (2) they help the ligaments with stability of the knee.

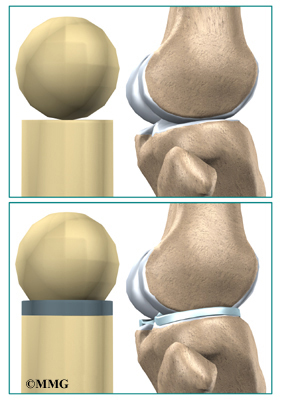

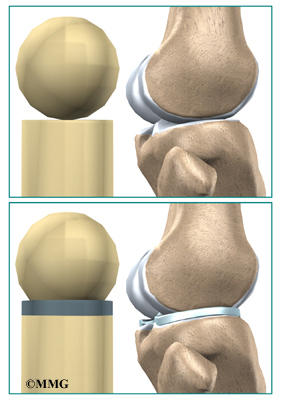

Imagine the knee as a ball resting on a flat plate. The ball is the end of the thighbone as it enters the joint, and the plate is the top of the shinbone. The menisci actually wrap around the round end of the upper bone to fill the space between it and the flat shinbone. The menisci act like a gasket, helping to distribute the weight from the femur to the tibia.

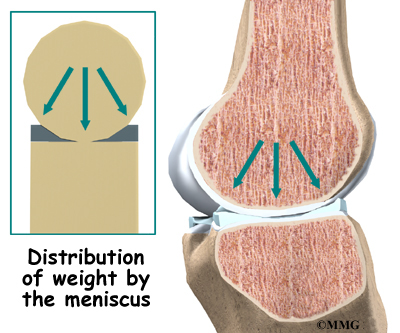

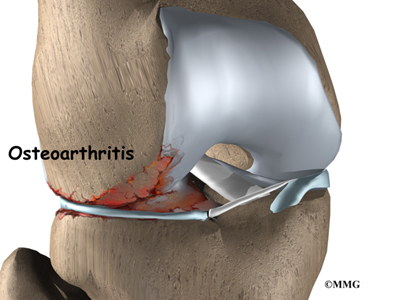

Without the menisci, any weight on the femur will be concentrated to one point on the tibia. But with the menisci, weight is spread out across the tibial surface. Weight distribution by the menisci is important because it protects the articular cartilage on the ends of the bones from excessive forces. Without the menisci, the concentration of force into a small area on the articular cartilage can damage the surface, leading to degeneration over time.

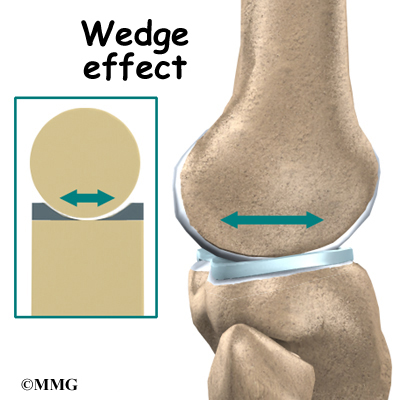

In addition to protecting the articular cartilage, the menisci help the ligaments with stability of the knee. The menisci make the knee joint more stable by acting like a wedge set against the bottom of a car tire. The menisci are thicker around the outside, and this thickness helps keep the round femur from rolling on the flat tibia. The menisci convert the tibial surface into a shallow socket. A socket is more stable and more efficient at transmitting the weight from the upper body than a round ball on a flat plate. The menisci enhance the stability of the knee and protect the articular cartilage from excessive concentration of force.

Taken all together, the ligaments of the knee are the most important structures that stabilize the joint. Remember, ligaments connect bones to bones. Without strong, tight ligaments to connect the femur to the tibia, the knee joint would be too loose. Unlike other joints in the body, the knee joint lacks a stable bony configuration. The hip joint, for example, is a ball that sits inside a deep socket. The ankle joint has a shape similar to a mortise and tenon, a way of joining wood used by craftsmen for centuries.

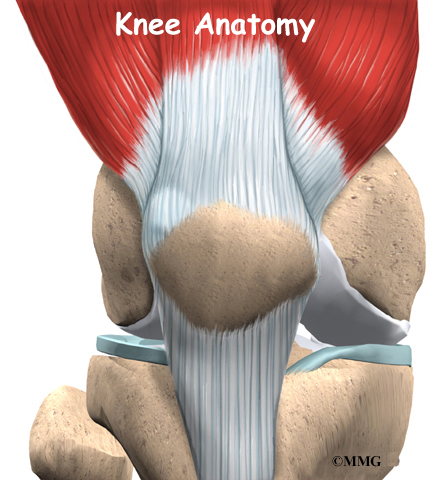

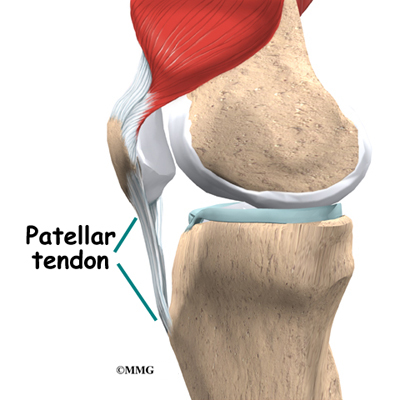

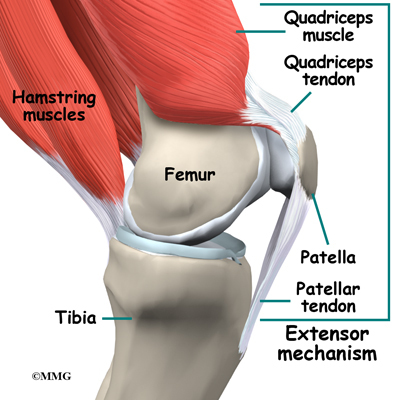

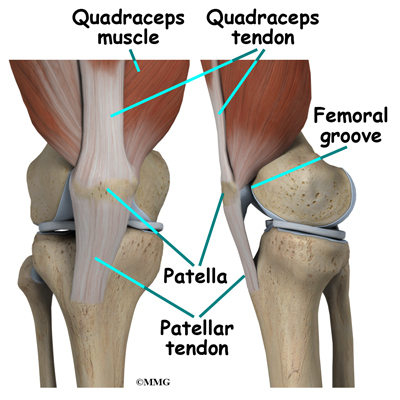

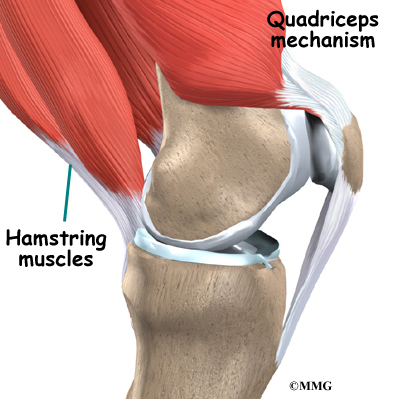

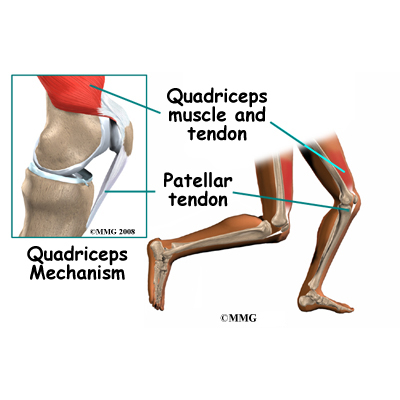

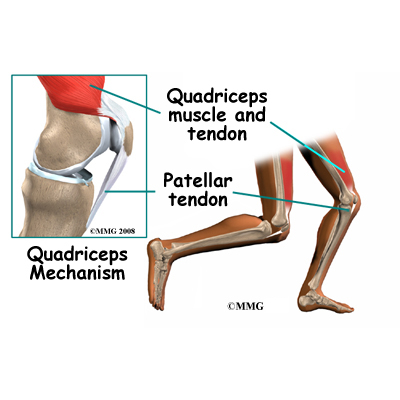

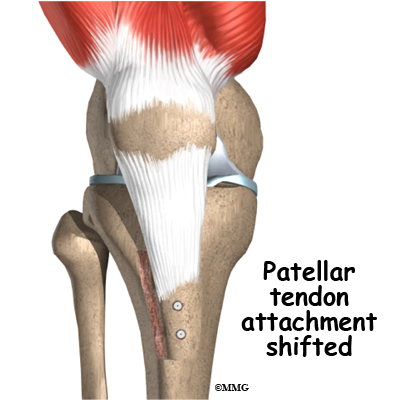

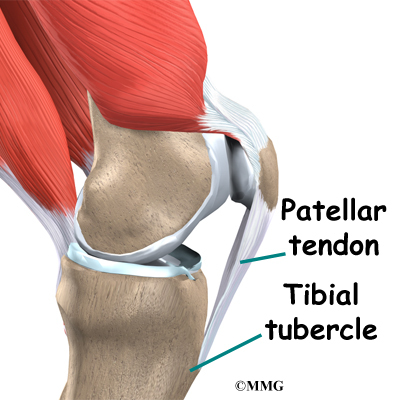

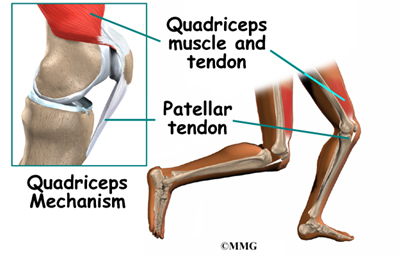

Tendons are similar to ligaments, except that tendons attach muscles to bones. The largest tendon around the knee is the patellar tendon. This tendon connects the patella (kneecap) to the tibia. This tendon covers the patella and continues up the thigh.

There it is called the quadriceps tendon since it attaches to the quadriceps muscles in the front of the thigh. The hamstring muscles on the back of the leg also have tendons that attach in different places around the knee joint. These tendons are sometimes used as tendon grafts to replace torn ligaments in the knee.

Muscles

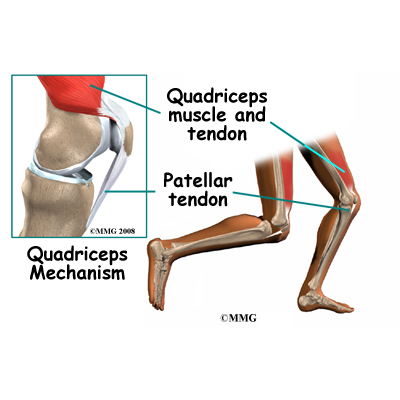

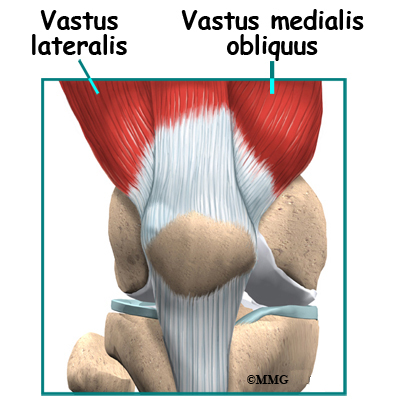

The extensor mechanism is the motor that drives the knee joint and allows us to walk. It sits in front of the knee joint and is made up of the patella, the patellar tendon, the quadriceps tendon, and the quadriceps muscles. The four quadriceps muscles in front of the thigh are the muscles that attach to the quadriceps tendon. When these muscles contract, they straighten the knee joint, such as when you get up from a squatting position.

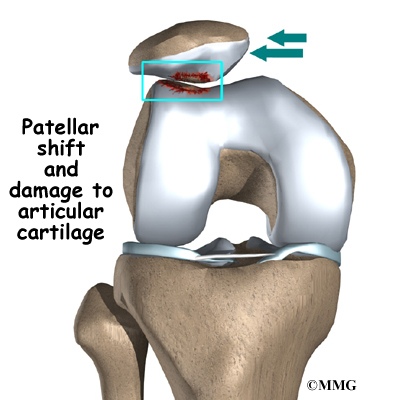

The way in which the kneecap fits into the patellofemoral groove on the front of the femur and slides as the knee bends can affect the overall function of the knee. The patella works like a fulcrum, increasing the force exerted by the quadriceps muscles as the knee straightens. When the quadriceps muscles contract, the knee straightens.

The hamstring muscles are the muscles in the back of the knee and thigh. When these muscles contract, the knee bends.

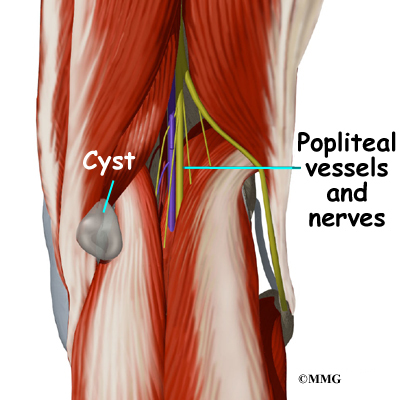

Nerves

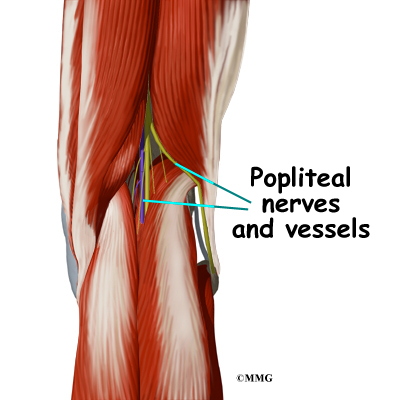

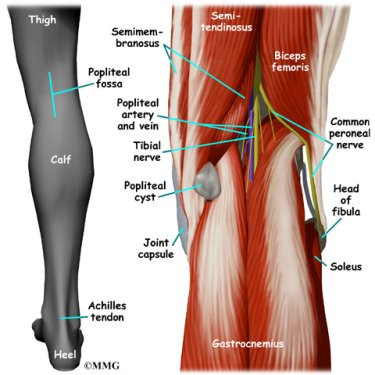

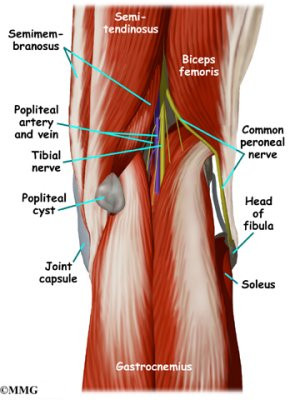

The most important nerves around the knee are the tibial nerve and the common peroneal nerve in the back of the knee. These two nerves travel to the lower leg and foot, supplying sensation and muscle control. The

large sciatic nerve splits just above the knee to form the tibial

nerve and the common peroneal nerve. The tibial nerve continues down

the back of the leg while the common peroneal nerve travels around the

outside of the knee and down the front of the leg to the foot. Both of

these nerves can be damaged by injuries around the knee.

Blood Vessels

The major blood vessels around the knee travel with the tibial nerve

down the back of the leg. The popliteal artery and popliteal vein are the largest blood supply to the leg and foot. If the popliteal artery is damaged beyond repair, it is very likely the leg will not be able

to survive. The popliteal artery carries blood to the leg and foot.

The popliteal vein carries blood back to the heart.

Summary

The knee has a somewhat unstable design. Yet it must support the body’s full weight when standing, and much more than that during walking or running. So it’s not surprising that knee problems are a fairly common complaint among people of all ages. Understanding the basic parts of the knee can help you better understand what happens when knee problems occur.

ACL Hamstring Tendon Graft Reconstruction

A Patient’s Guide to Hamstring Tendon Graft Reconstruction of the ACL

Introduction

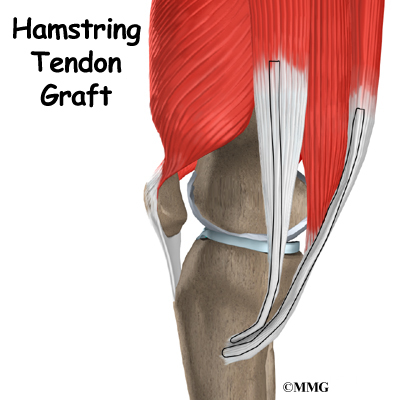

When the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) in the knee is torn or injured, surgery may be needed to replace it. There are many different ways to do this operation. One is to take a piece of the hamstring tendon from behind the knee and use it in place of the torn ligament. When arranged into three or four strips, the hamstring graft has nearly the same strength as other available grafts used to reconstruct the ACL.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the knee are treated during surgery

- how surgeons perform the operation

- what to expect before and after the procedure

Anatomy

What parts of the knee are involved?

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect the ends of bones together. The ACL is located in the center of the knee joint where it runs from the backside of the femur (thighbone) to the front of the tibia (shinbone).

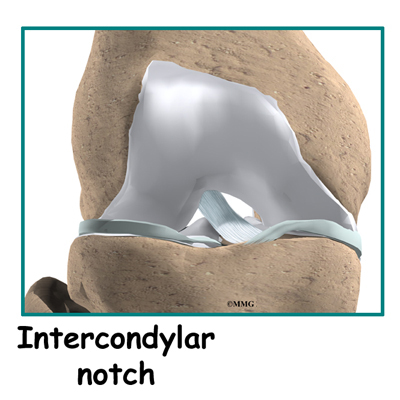

The ACL runs through a special notch in the femur called the intercondylar notch and attaches to a special area of the tibia called the tibial spine.

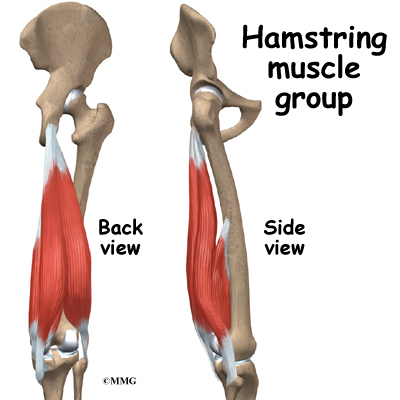

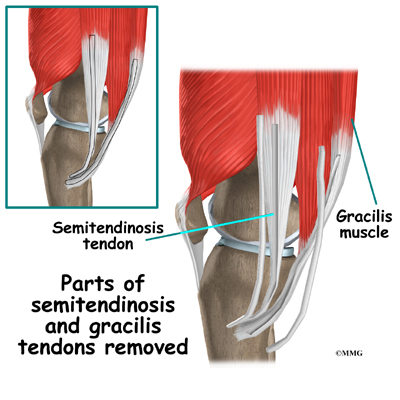

The hamstrings make up the bulk of the muscles in back of the thigh. The hamstrings are formed by three muscles and their tendons: the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and biceps femoris. The top of the hamstrings connects to the ischial tuberosity, the small bony projection on the bottom of the pelvis, just below the buttocks. (There is one ischial tuberosity on the left and one on the right.)

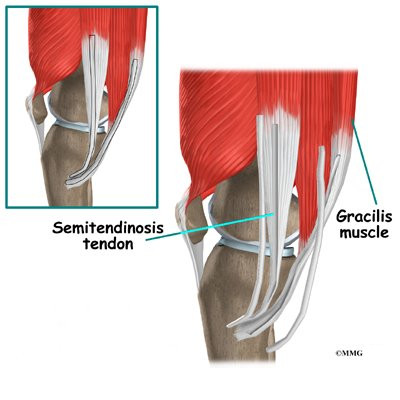

The hamstring muscles run down the back of the thigh. Their tendons cross the knee joint and connect on each side of the tibia. The graft used in ACL reconstruction is taken from the hamstring tendon (semitendinosus) along the inside part of the thigh and knee. Surgeons also commonly include a tendon just next to the semitendinousus, called the gracilis.

The hamstrings function by pulling the leg backward and by propelling the body forward while walking or running. This movement is called hip extension. The hamstrings also bend the knees, a motion called knee flexion.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to accomplish?

The main goal of ACL surgery is to keep the tibia from moving too far forward under the femur bone and to get the knee functioning normally again.

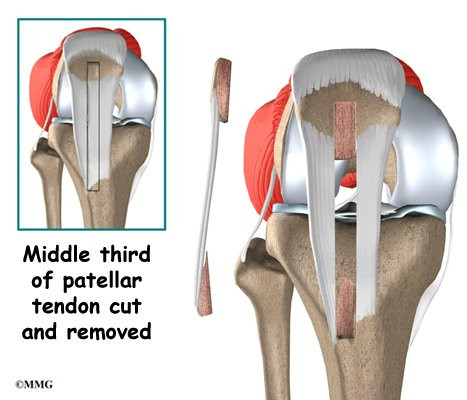

There are two grafts commonly used to repair a torn ACL. One is a strip of the patellar tendon below the kneecap. The other is the hamstring tendon graft. For a long time, the patellar tendon was the preferred choice because it is easy to get to, holds well in its new location, and heals fast. One big drawback to grafting the patellar tendon is pain at the front of the knee after surgery. This can be severe enough to prevent any pressure on the knee, such as kneeling.

For this reason, a growing number of surgeons are using grafted tissue from the hamstring tendon. There are no major differences in the final results of these two methods. When it comes to symptoms after surgery, joint strength and stability, and ability to use the knee, either method is good. However, with the hamstring tendon graft, there are generally no problems kneeling and no pain in the front of the knee.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Patellar Tendon Graft Reconstruction of the ACL

Preparation

What do I need to know before surgery?

You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this preoperative visit is to record a baseline of information. Your therapist will check your current pain levels, your ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each knee.

A second purpose of the preoperative visit is to prepare you for surgery. Your therapist will teach you how to walk safely using crutches or a walker. And you’ll begin learning some of the exercises you’ll use during your recovery.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the surgery center early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during the operation?

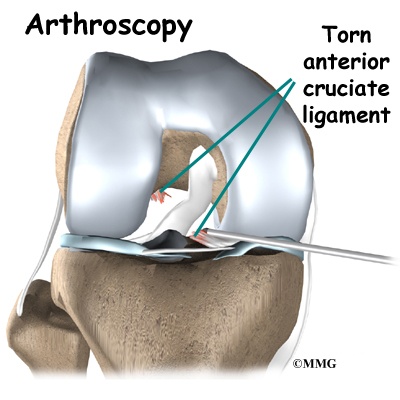

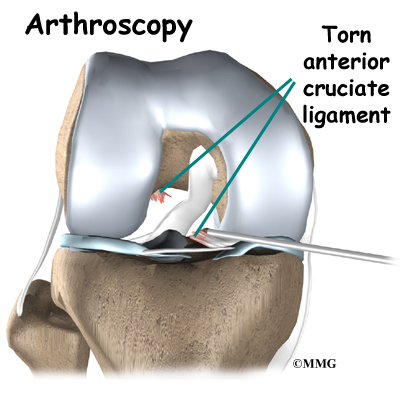

Most surgeons perform this surgery using an arthroscope, a small fiber-optic TV camera that is used to see and operate inside the joint. Only small incisions are needed during arthroscopy for this procedure. The surgery doesn’t require the surgeon to open the knee joint.

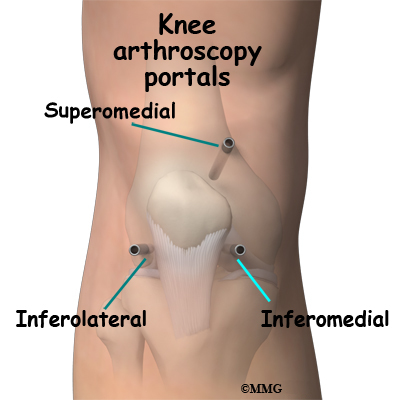

Before surgery you will be placed under either general anesthesia or a type of spinal anesthesia. The surgeon begins the operation by making two small openings into the knee, called portals. These portals are where the arthroscope and surgical tools are placed into the knee. Care is taken to protect the nearby nerves and blood vessels.

An incision is also made along the inside edge of the knee, just over where the hamstring tendons attach to the tibia. Working through this incision, the surgeon takes out the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons. Some surgeons prefer to use only the semitendinosus tendon and do not disrupt the gracilis tendon.

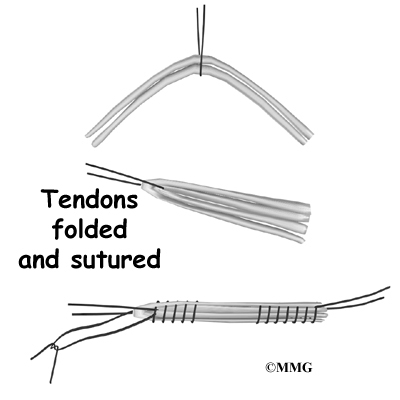

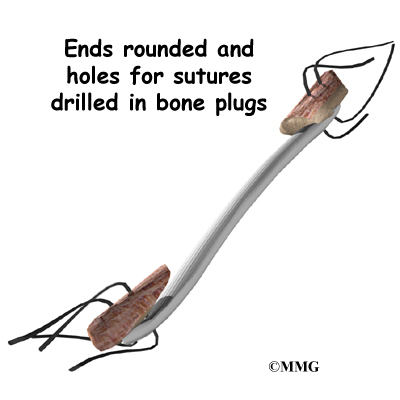

The tendons are arranged into three or four strips, which increases the strength of the graft. The surgeon stiches the strips together to hold them in place.

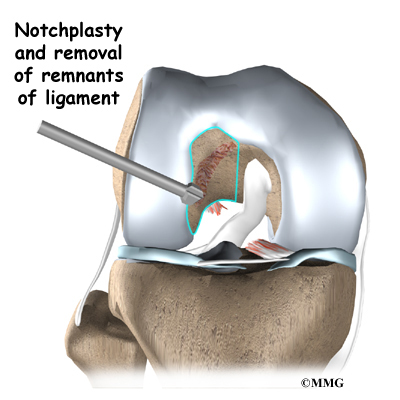

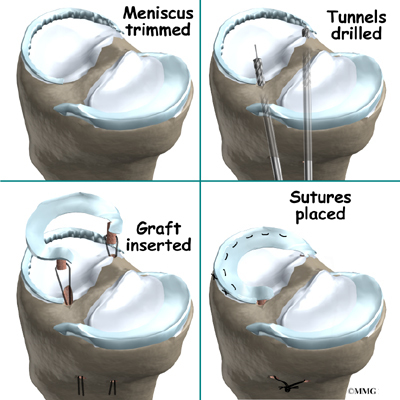

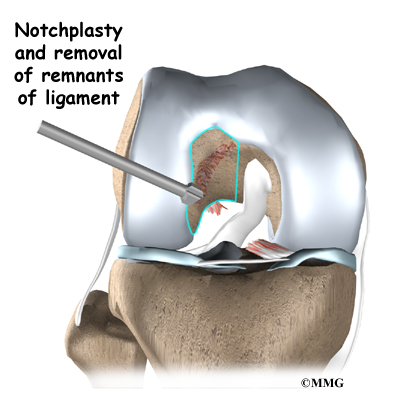

Next, the surgeon prepares the knee to place the graft. The remnants of the original ligament are removed. The intercondylar notch (mentioned earlier) is enlarged so that nothing will rub on the graft. This part of the surgery is referred to as a notchplasty.

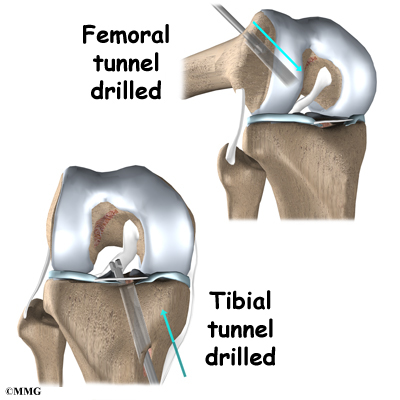

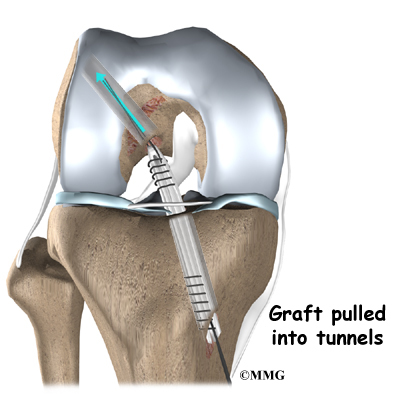

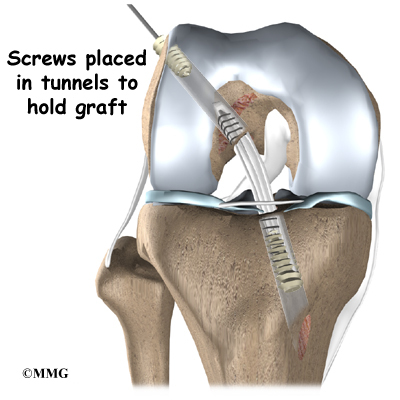

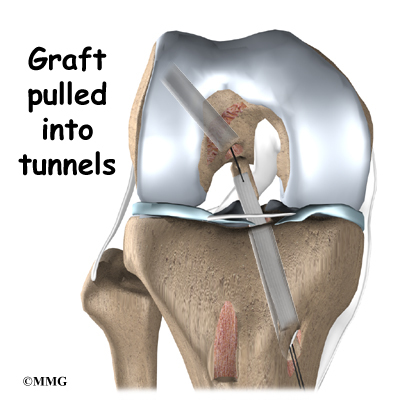

Once this is done, holes are drilled in the tibia and the femur to place the graft. These holes are placed so that the graft will run between the tibia and femur in the same direction as the original ACL. The graft is then pulled into position through the drill holes. Screws or staples are used to hold the graft inside the drill holes.

To keep fluid from building up in your knee, the surgeon may place a tube in your knee joint. The portals and skin incisions are then stitched together, completing the surgery.

Complications

What can go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following hamstring tendon graft reconstruction of the ACL are

- anesthesia complications

- thrombophlebitis

- infection

- problems with the graft

- problems at the donor site

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

View animation of pulmonary embolism

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when blood clots form in the large veins of the leg. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible after surgery. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Following surgery, it is possible that the surgical incision can become infected. This will require antibiotics and possibly another surgical procedure to drain the infection.

Problems with the Graft

After surgery, the body attempts to develop a network of blood vessels in the new graft. This process, called revascularization, takes about 12 weeks. The graft is weakest during this time, which means it has a greater chance of stretching or rupturing. A stretched or torn graft can occur if you push yourself too hard during this period of recovery. When revascularization is complete, strength in the graft gradually builds. A second surgery may be needed to replace the graft if it is stretched or torn.

Problems at the Donor Site

Problems can occur at the donor site (the area behind the leg where the hamstring graft was taken from the thigh). A potential drawback of taking out a piece of the hamstring tendon is a loss of hamstring muscle strength.

The main function of the hamstrings is to bend the knee (knee flexion). This motion may be slightly weaker in people who have had a hamstring tendon graft to reconstruct a torn ACL. Some studies, however, indicate that overall strength is not lost because the rest of the hamstring muscle takes over for the weakened area. Even the portion of muscle where the tendon was removed works harder to make up for the loss.

The hamstring muscles sometimes atrophy (shrink) near the spot where the tendon was removed. This may explain why some studies find weakness when the hamstring muscles are tested after this kind of ACL repair. However, the changes seem to mainly occur if both the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons were used. And the weakness is mostly noticed by athletes involved in sports that require deep knee bending. This may include participants in judo, wrestling, and gymnastics. These athletes may want to choose a different method of repair for ACL tears.

The body attempts to heal the donor site by forming scar tissue. This new tissue is not as strong as the original hamstring tendon. Because of this, there is a small chance of tearing the healing tendon, especially if the hamstrings are worked too hard in the early weeks of rehabilitation following surgery.

After Surgery

What should I expect after surgery?

You may use a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine immediately afterward to help the knee begin moving and to alleviate joint stiffness. The machine straps to the leg and continuously bends and straightens the joint. This continuous motion is thought to reduce stiffness, ease pain, and keep extra scar tissue from forming inside the joint. The CPM is often used with a form of cold treatment that circulates cold water through hoses and pads around your knee.

Most ACL surgeries are now done on an outpatient basis. Many patients go home the same day as the surgery. Some patients stay one to two nights in the hospital if necessary. The tube placed in your knee at the end of the surgery is usually removed after 24 hours.

Your surgeon may also have you wear a protective knee brace for a few weeks after surgery. You’ll use crutches for two to four weeks in order to keep your knee safe, but you’ll probably be allowed to put a comfortable amount of weight down while you’re up and walking.

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

Patients usually take part in formal physical therapy after ACL reconstruction. The first few physical therapy treatments are designed to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery. The goal is to help you regain full knee extension as soon as possible.

The physical therapist will choose treatments to get the thigh muscles toned and active again. Patients are cautioned about overworking their hamstrings in the first six weeks after surgery. They are often shown how to do isometric exercises for the hamstrings. Isometrics work the muscles but keep the joint in one position.

As the rehabilitation program evolves, more challenging exercises are chosen to safely advance the knee’s strength and function. Specialized balance exercises are used to help the muscles respond quickly and without thinking. This part of treatment is called neuromuscular training. If you need to stop suddenly, your muscles must react with just the right amount of speed, control, and direction. After ACL surgery, this ability doesn’t come back completely without exercise.

Neuromuscular training includes exercises to improve balance, joint control, muscle strength and power, and agility. Agility makes it possible to change directions quickly, go faster or slower, and improve starting and stopping. These are important skills for walking, running, and jumping, and especially for sports performance.

When you get full knee movement, your knee isn’t swelling, and your strength and muscle control are improving, you’ll be able to gradually go back to your work and sport activities. Some surgeons prescribe a functional brace for athletes who intend to return quickly to their sports.

Ideally, you’ll be able to resume your previous lifestyle activities. However, athletes are usually advised to wait at least six months before returning to their sports. Most patients are encouraged to modify their activity choices.

You will probably be involved in a progressive rehabilitation program for four to six months after surgery to ensure the best result from your ACL reconstruction. In the first six weeks following surgery, expect to see the physical therapist two to three times a week. If your surgery and rehabilitation go as planned, you may only need to do a home program and see your therapist every few weeks over the four to six month period.

Bipartite Patella

A Patient’s Guide to Bipartite Patella

Introduction

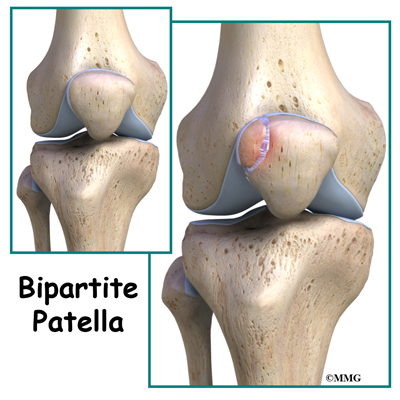

Bipartite patella is a congenital condition (present at birth) that occurs when the patella (kneecap) is made of two bones instead of a single bone. Normally, the two bones would fuse together as the you grow. But in bipartite patella, they remain as two separate bones. About one per cent of the population has this condition. Boys are affected much more often than girls. When this condition is discovered in adulthood it is oftentimes an “incidental finding”.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the knee are involved

- how this condition develops

- how doctors diagnose this condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What is the patella and what does it do?

The knee is the meeting place of two important bones in the leg, the femur (the thighbone) and the tibia (the shinbone). The patella (kneecap) is the moveable bone that sits in front of the knee. This unique bone is wrapped inside a tendon that connects the large muscles on the front of the thigh, the quadriceps muscles, to the lower leg bone.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Causes

What causes this condition?

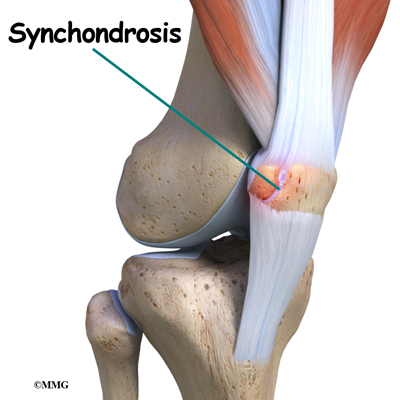

The patella starts out as a piece of fibrous cartilage. It turns into bone or ossifies as part of the growth process. Each bone has an ossification center. This is the first area of the structure to start changing into bone.

Most bones (including the patella) only have one primary ossification center. But in some cases, a second ossification center is present. Normally, these two centers of bone will fuse together during late childhood or early adolescence. If they don’t ossify together, then the two pieces of bone remain connected by fibrous or cartilage tissue. This connective tissue is called a synchondrosis.

The most common location of the second bone is the supero-lateral (upper outer) corner of the patella. But the problem can occur at the bottom of the patella or along the side of the kneecap.

Injury or direct trauma to the synchondrosis can cause a separation of this weak union leading to inflammation. Repetitive microtrauma can have the same effect. The cartilage has a limited ability to repair itself. The increased mobility between the main bone and the second ossification center further weakens the synchondrosis resulting in painful symptoms.

Symptoms

What does bipartite patella feel like?

Most of the time, there are no symptoms. Sometimes there is a bony bump or place where the bone sticks out more on one side than the other. If inflammation of the fibrous tissue between the two bones occurs, then painful symptoms develop directly over the kneecap. The pain is usually described as dull aching. There may be some swelling.

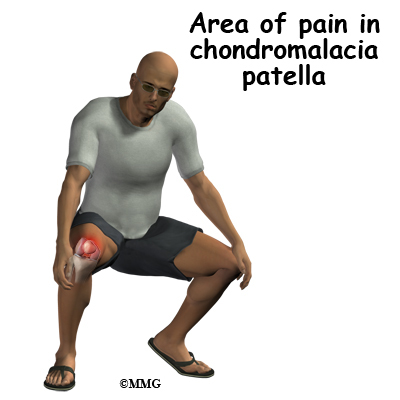

Movement of the knee can be painful, especially when bending the joint. Atrophy of the quadriceps and malalignment of the patella can lead to patellar tracking problems. Squatting, stair climbing, weight training, and strenuous activity aggravate the knee causing increased symptoms. For the runner, running down hill causes increased pain, tenderness, and swelling.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

Most of the time, this condition is seen on X-rays of the knee that are taken for some other reason. This is referred to as an incidental finding. Sometimes, it is mistaken for a fracture of the patella. But since the problem usually affects both knees, an X-ray of the other knee showing the same condition can confirm the diagnosis.

MRIs or bone scans are useful when a fracture is suspected but doesn’t show up on the X-rays. The presence of fibrocartilaginous material between the two bones helps confirm a diagnosis of bipartite patella. An MRI can show the condition of articular cartilage at the patellar-fragment interface. The lack of bone marrow edema helps rule out a bone fracture. CT scans will show the bipartite fragment but are not as helpful as MRIs because bone marrow or soft tissue edema does not show up, so it’s still not clear from CT findings whether the symptoms are from the fragment or fracture.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Most of the time, no treatment is necessary. Most people who have a bipartite patella, probably don’t even know it. But if an injury occurs and/or painful symptoms develop, then treatment may be needed.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Conservative care involves rest, over-the-counter nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen, and activity modification. Avoiding deep flexion such as squatting, excess use of the stairs, and resisted weight training are advised.

Separation of the synchondrosis can be treated with immobilization for four to six weeks. The knee is placed in full extension using a cylinder cast, knee immobilizer, or dynamic patellar brace. An immobilizer is a removable splint. It’s usually only taken off to wash the leg and remains in place the rest of the time. The dynamic brace immobilizes the knee in an extended (straight-leg) position with limited flexion (up to 30 degrees). The brace reduces pain by decreasing the pull on the patella from the quadriceps muscle. Once healing occurs and the cast or brace is no longer needed, then stretching exercises of the quadriceps muscle are prescribed.

Surgery

If conservative care with immobilization is not successful in alleviating swelling and pain, then surgery may be suggested. When the bipartite fragment is small, then the surgeon can simply remove the smaller fragment of bone. When the bipartite fragment is larger and also contains part of the joint surface, the surgeon may decide to try and force the two fragments to heal together or fuse. The connective tissue between the two fragments is removed first and the two bony fragments are then held together or stabilized with a metal screw or

pin. This is called internal fixation. The two fragments of bone heal

together or fuse, creating a solid connection between the two fragments. Although successful in reuniting the patella, the procedure may require several weeks of immobilization. As a result, knee stiffness may occur. This usually requires physical therapy once the bones have healed to regain strength and motion.

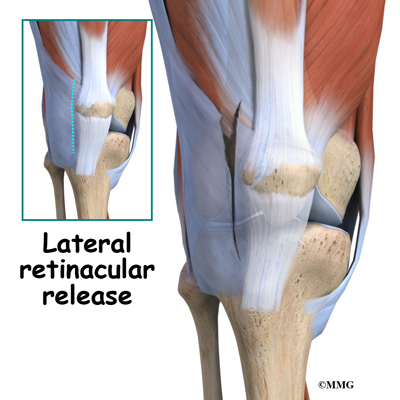

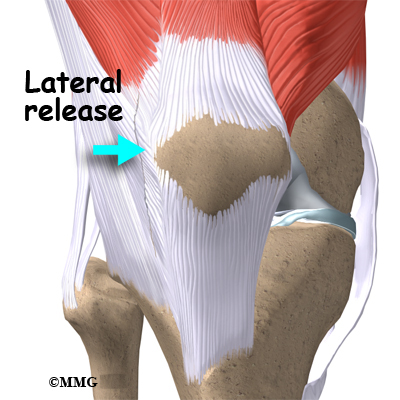

Another potential treatment option is a procedure called a lateral

retinacular release. It may be beneficial to remove the constant pull

of the vastus lateralis tendon (a part of the large quadriceps muscle

of the thigh) where it attaches to the bone of the bipartite fragment of the upper, outer patella. Simply cutting this attachment reduces the constant pull on the bony fragment. Healing of the two fragments may occur as a result.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after Treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Most patients respond well to activity modification and immobilization. When the X-ray shows complete ossification of the two bone fragments, then you’ll be able to return to your regular activities. If there is no improvement after three months of conservative care, then surgery is considered.

After Surgery

Usually, the removal of a bipartite patella is a simple surgery with prompt relief of pain and quick recovery. Athletes can expect full range of motion, a stable knee, and a fairly rapid return to normal activity (one to two months). But runners and other athletes who have had an extended time of immobility, muscle weakness and atrophy, loss of normal joint motion, and patellar tracking problems may require a special rehab program. A physical therapist will prescribe and monitor a rehabilitation program starting with range of motion and quadriceps strengthening exercises.

Athletes will be progressed quickly to restore full motion and strength. An aerobic program to improve cardiovascular endurance is often needed after so many months of inactivity. Proprioception and functional activities are added in order to prepare the individual to return to full sports participation. Proprioceptive exercises help restore the joint’s sense of position. Proprioceptive activities are needed to restore normal movement and prevent further injury.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis of the Knee

A Patient’s Guide to Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS) of the Knee

Introduction

Pigmented villonodular synovitis of the knee (PVNS) is a very rare disease. Pigmented villonodular synovitis is most often painless inflammation or swelling, and overgrowth of the lining of a joint. The growth can invade the nearby bone.

Eighty per cent of the time pigmented villonodular synovitis affects just one joint of the body, primarily the knee joint. The hip, shoulder, and the smaller joints in the hands and feet can also be affected.

Pigmented villonodular synovitis occurs in less than two persons per million per year. It occurs in both men and women commonly between the ages of 20 and 45 years.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the knee are involved

- how this condition develops

- how doctors diagnose this condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the knee are affected?

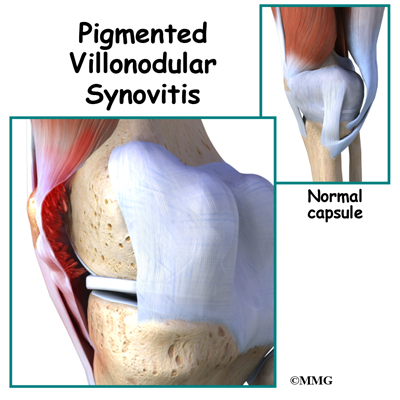

There are several types of joints in the body, but pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) generally affects the synovial joints. Synovial joints are the most common joints in the body (90 percent). They are the most mobile of the joints.

The knee joint is a synovial joint. It is surrounded by synovial tissue which is tough. It is not stretchy or elastic. The synovial tissue forms a covering called a joint capsule around the joint. The joint capsule helps stabilize the joint. The soft padding on the ends of the bones is called articular cartilage. This helps the joint move smoothly. Ligaments and tendons help hold the joint together.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Causes

What causes this condition?

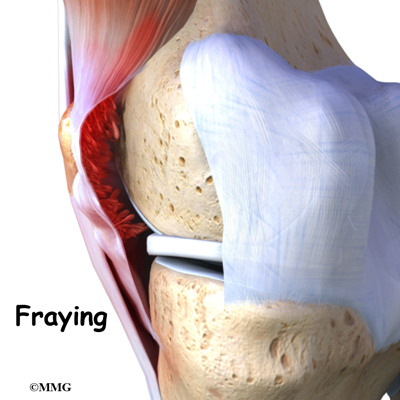

Villous means hair-like. In pigmented villonodular synovitis, the tissue that is affected may look frayed or hair-like. The synovial tissue can also appear folded. Sometimes the tissue will have round bumps or nodules. The nodular type is usually seen in tendons. Tissue affected by pigmented villonodular synovitis can contain deposits of fat. Pigmented means colored. The synovium and its fluid is often a brown color instead of clear. This is because blood, which contains iron, is deposited in the fluid.

Pigmented Villonodular Synovitis (PVNS) at one time was thought to be a form of malignant cancer. It is now considered a benign, or non-cancerous, inflammatory process.

It is not known if PVNS is due to injury. Patients have reported injury at some time to the affected joint, others do not. There does not seem to be a genetic cause. It happens in both men and women generally between the ages of 20 and 45 years. It occurs in less than two persons per million per year.

The exact cause is unknown. Some doctors believe it’s caused by abnormal metabolism of fat. Others think it may be caused by repetitive inflammation. Some feel that blood within the joint may cause the inflammatory change.

Symptoms

What are the symptoms?

Symptoms of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) of the knee include inflammation, swelling, stiffness, and tenderness around the joint. The pain can come and go.

Symptoms may feel like arthritis. The pain comes on slowly in the joint. There may be swelling, tenderness, and limited movement of the knee. The symptoms can come and go. Eighty per cent of the time PVNS affects the knee.

Sometimes a popping feeling is felt in the knee. Tenderness in the front part of the knee near the knee cap is usually noticed. The symptoms are rather “non-specific”, meaning that they can act like other problems. PVNS of the knee can easily be mistaken for a torn meniscus, or problems with the patella (knee cap).

There are two types of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). When it occurs in one large synovial joint of the body, such as the knee, it is considered diffuse. This is because the inflammation is more widespread within the joint. The synovial capsule, bursa, and tendon sheaths around the joint can all be involved. Even the bones in the knee joint can be affected.

The other type of pigmented villonodular synovitis is localized, or focal. This form is rare. It usually affects just the tendon sheaths around smaller joints in the hands and feet. This means there will be localized swelling and likely some tenderness along the tendons.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

Your doctor will want to do a physical examination. He/she will want to measure range of motion of the knee joint. Your doctor will also want to determine if there is any swelling, nodules, tenderness, or fluid in the joint. Swelling in your knee may feel warm and be somewhat tender to palpation.

Imaging plays an important role in the diagnosis of pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS). Often, X-rays will be normal. Sometimes there will be cysts in the bone at the joint caused by the invasion of PVNS. There are usually no wear and tear changes like with arthritis.

MRI does not use x-rays. It uses magnetic waves. It allows the doctor to

see your tissues and bones in thin slices. You will need an MRI with

contrast. This means that you will have to have an IV inserted. The contrast

material is called gladolinium. The gladolinium will go where cells are more

active in your body. Cells tend to be more active in areas where there is

inflammation, and in tumors.

If PVNS has invaded the bone, your doctor will likely want you to have a computed tomography (CT) scan. This is a special form of xray. Like the MRI, it takes pictures in slices. This will require the injection of intravenous contrast so that tissues can be better evaluated.

Your doctor may want to remove (aspirate) fluid from the joint that is affected. This is called arthrocentesis. The fluid is taken out with a needle. The fluid is then tested in the lab. If PVNS is the cause of the symptoms, most of the time the fluid will contain blood.

A contrast material may be injected into the joint after aspiration which will enhance the imaging studies. The contrast material will show irregular and nodular defects in imaging studies. This testing is called an arthrogram.

A biopsy of the affected tissue may be suggested. This can certainly confirm the diagnosis of PVNS. Computed tomography is used to perform the biopsy. Pictures are taken while your doctor is placing the needle in the tissue to be removed and tested. The tissue that is removed is then looked at in the lab. If pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS) is present, the synovium will be thickened. It will likely have both villous and nodular extra growth. Inflammation cells called giant cells are usually present. The synovium and fluid will be a brown color. This is due to deposits of iron in the blood.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

There is no nonsurgical treatment. Because the PVNS can grow and invade bone, surgery is the recommended treatment.

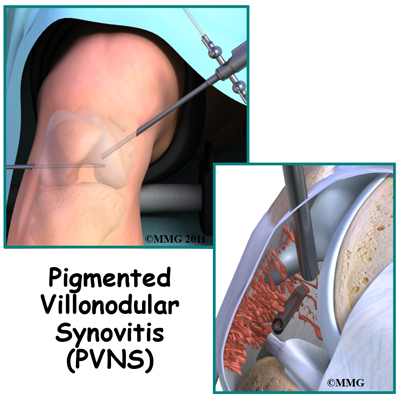

Surgery

Since PVNS can invade the joint, the most effective treatment is surgery. Removing the synovium and involved tissue is necessary. Since PVNS can grow back, sometimes radiation is recommended. Sometimes joint replacement may be needed.

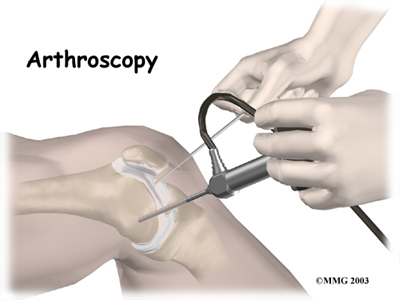

The recommended treatment for PVNS is removal of all the affected tissue. The surgery is called a synovectomy. Most of the time this surgery can be done with an arthroscope. Your surgeon makes tiny cuts in the skin over your joint. A thin tube with a tiny camera is used so your surgeon can see inside the joint. Instruments for cutting, smoothing, and removing tissue are passed through another thin tube. Arthroscopy is done as a “same day” surgery, meaning you can go home the same day.

Sometimes the synovectomy is done by opening the knee joint. In diffuse pigmented villonodular synovitis (PVNS), all the tissue, including any bone that seems to be affected is removed. Grafting, or replacing the bone with transplanted bone may be necessary to maintain the joint. In some instances, a total joint replacement of the knee is necessary.

Diffuse PVNS grows back in nearly 50 percent of cases. If your surgeon is concerned that not all of the affected tissue was removed, you may have to have radiation therapy. It is also used if there is recurrence (return) of PVNS after it has been removed.

Radiation therapy is determined by a specialist called a radiation oncologist. A machine that emits radiation waves may be used to treat the affected area. Other times, radiation pellets can be inserted in the area that needs to be treated. This helps to keep the radiation contained, so that it harms as little as possible of the normal tissue.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after Treatment?

After Surgery

Rehabilitation usually involves physical therapy. Range-of-motion exercises are important and may be started right away. Strengthening and conditioning exercises will allow you to return to your previous level of activity. When surgery involves the leg, walking with a walker or crutches may be recommended at first.

If knee joint replacement is required, you will likely be hospitalized for three to five days. A continuous passive motion (CPM) machine may be used while in the hospital or started when you return home. Your leg will rest in the machine that is plugged into a wall outlet. The machine slowly bends you knee. This allows range of motion for several minutes or hours at a time. Pain will need to be treated for several weeks. You will need to be careful about keeping your incision clean, and monitor closely for infection.

Use of cold packs will help minimize swelling from surgery for the first several days. You may need pain medication if over the counter anti-inflammatories or acetaminophen (Tylenol®) do not control your pain.

After treatment, your doctor will want you to follow up with him periodically. Repeat MRI is needed to evaluate possible return of the PVNS.

Knee Arthroscopy

A Patient’s Guide to Knee Arthroscopy

Introduction

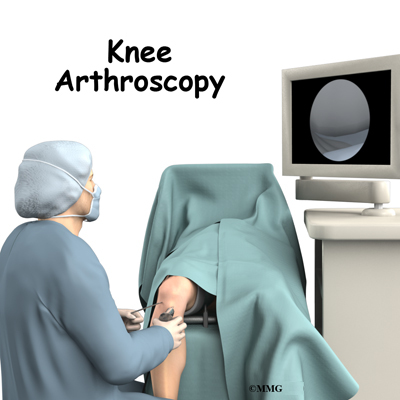

The use of arthroscopy has revolutionized many different types of orthopedic surgery. During knee arthroscopy, a small video camera attached to a fiberoptic lens is inserted into the body to allow a physician or surgeon to see without making a large incision (arthro means joint scopy means look). The knee was the first joint in which the arthroscope was commonly used to both diagnose problems and to perform surgical procedures inside the knee joint.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the knee are involved

- what types of conditions can be treated

- what to expect after surgery

Anatomy

What parts of the knee are involved?

The knee joint is formed where the femur (lower end of the thighbone) connects with the tibia (upper end of the main lower leg bone). On the front of the joint is the patella (kneecap). The patella is what is called a sesamoid bone that is a part of the extensor mechanism of the knee joint. The extensor mechanism connects the large muscles of the thigh to the tibia; contracting the thigh muscles pulls on the tibia and allows us to straighten the knee. The parts of the extensor mechanism include the thigh muscles, the quadriceps tendon, the patella and the patella tendon.

The knee joint is surrounded by a water tight pocket called the joint capsule. This capsule is formed by the knee ligaments, connective tissue and synovial tissue. When the joint capsule is filled with sterile saline and is distended, the surgeon can insert the arthroscope into the pocket that is formed, turn on the lights and the camera and see inside the knee joint as if looking into an aquarium. The surgeon can see nearly everything that is inside the knee joint including: (1) the joint surfaces of the tibia, femur and patella, (2) the two menisci, (3) the two cruciate ligaments, and (4) the synovial lining of the joint.

There is one meniscus on each side of the knee joint. The C-shaped medial meniscus is on the inside part of the knee, closest to your other knee. (Medial means closer to the middle of the body.) The U-shaped lateral meniscus is on the outer half of the knee joint. (Lateral means further out from the center of the body.)

The menisci (plural for meniscus) protect the articular cartilage on the surfaces of the thighbone (femur) and the shinbone (tibia). Articular cartilage is the smooth, slippery material that covers the ends of the bones that make up the knee joint. The articular cartilage allows the joint surfaces to slide against one another without damage to either surface.

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect the ends of bones together. The Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) is located in the center of the knee joint where it runs from the backside of the femur (thighbone) to connect to the front of the tibia (shinbone).

The ACL runs through a special notch in the femur called the intercondylar notch and attaches to a special area of the tibia called the tibial spine.

The ACL is the main controller of how far forward the tibia moves under the femur. This is called anterior translation of the tibia. If the tibia moves too far, the ACL can rupture. The ACL is also the first ligament that becomes tight when the knee is straightened. If the knee is forced past this point, or hyperextended, the ACL can also be torn.

The Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) is located near the back of the knee joint. It attaches to the back of the femur (thighbone) and the back of the tibia (shinbone) behind the ACL.

The PCL is the primary stabilizer of the knee and the main controller of how far backward the tibia moves under the femur. This motion is called posterior translation of the tibia. If the tibia moves too far back, the PCL can rupture.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Rationale

What does my surgeon hope to accomplish?

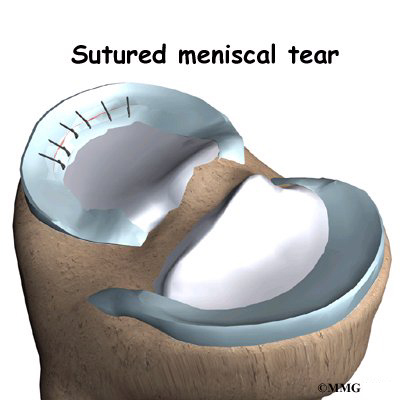

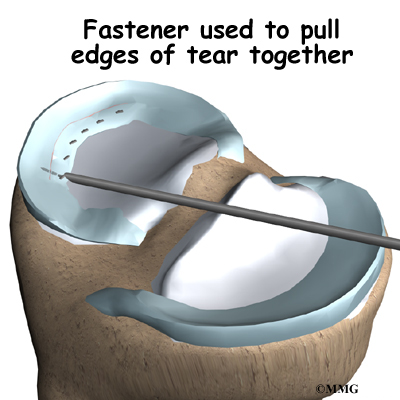

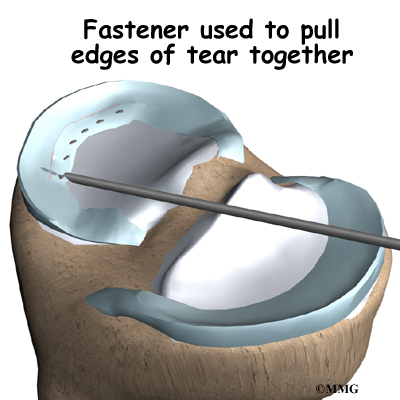

When knee arthroscopy first became widely available in the 1970’s it was used primarily to look inside the knee joint and make a diagnosis. Today, knee arthroscopy is used in performing a wide range of different types of surgical procedures on the knee joint including confirming a diagnosis, removing loose bodies, removing or repairing a torn meniscus, reconstructing torn ligaments, repairing articular cartilage and fixing fractures of the joint surface.

Your surgeon’s goal is to fix or improve your problem by performing a suitable surgical procedure; the arthroscope is a tool that improves the surgeons ability to perform that procedure. The arthroscope image is magnified and allows the surgeon to see better and clearer. The arthroscope allows the surgeon to see and perform surgery using much smaller incisions. This results in less tissue damage to normal tissue and can shorten the healing process. But remember, the arthroscope is only a tool. The results that you can expect from a knee arthroscopy depend on what is wrong with your knee, what can be done inside your knee to improve the problem and your effort at rehabilitation after the surgery.

Preparations

What do I need to know before surgery?

You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, be sure and talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this preoperative visit is to record a baseline of information. The therapist will check your current pain levels, ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each knee.

A second purpose of the preoperative visit is to prepare you for surgery. The therapist will teach you how to walk safely using crutches or a walker. And you’ll begin learning some of the exercises you’ll use during your recovery.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted for surgery early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during the procedure?

Before surgery you will be placed under either general anesthesia or a type of spinal anesthesia. In simple cases, local anesthesia may be adequate. Special braces are attached to the operating room table. These are used to safely cradle the leg and allows the surgeon to move the leg and bend the knee easily. Finally, sterile drapes are placed to create a sterile environment for the surgeon to work. There is a great deal of equipment that surrounds the operating table including the TV screens, cameras, light sources and surgical instruments.

The surgeon begins the operation by making two or three small openings into the knee, called portals. These portals are where the arthroscope and surgical instruments are placed inside the knee. Care is taken to protect the nearby nerves and blood vessels. A small metal or plastic tube (or cannula) will be placed through one of the portals to inflate the knee with sterile saline.

The arthroscope is a small fiber-optic tube that is used to see and operate inside the joint. The arthroscope is a small metal tube about 1/4 inch in diameter (slightly smaller than a pencil) and about seven inches in length. The fiberoptics inside the metal tube of the arthroscope allows a bright light and TV camera to be connected to the outer end of the arthroscope. The light shines through the fiberoptic tube and into the knee joint. A TV camera is attached to the lens on the outer end of the arthroscope. The TV camera projects the image from inside the knee joint on a TV screen next to the surgeon. The surgeon actually watches the TV screen (not the knee joint) while moving the arthroscope to different places inside the knee joint.

Over the years since the invention of the arthroscope, many very specialized instruments have been developed to perform different types of surgery using the arthroscope to see what is going on while the instruments are being used. Today, many surgical procedures that once required large incisions for the surgeon to see and fix the problem can be one with much smaller incisions. For example, simple removal of a torn meniscus or loose body can be done using two small 1/4 inch incisions. More extensive surgical procedures such as ligament reconstruction or fracture repair may require larger incisions.

Once the surgical procedure is complete, the arthroscopic portals and surgical incisions will be closed with sutures or surgical staples. A large bandage will be applied from mid thigh to the toes. Wrapping the entire leg with a compressive bandage reduces swelling and helps prevent blood clots in the leg. Once the bandage has been placed, you will be taken to the recovery room.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur during knee arthroscopy. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following knee arthroscopy are

- anesthesia complications

- thrombophlebitis

- infection

- equipment failure

- slow recovery

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when blood clots form in the large veins of the leg. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible after surgery. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Following knee arthroscopy, it is possible that a postoperative infection may occur. This is very uncommon and happens in less than 1% of cases. You may experience increased pain, swelling, fever and redness or drainage from the incisions. You should alert your surgeon if you think you are developing an infection.

Infections are of two types: superficial or deep. A superficial infection may occur in the skin around the incisions or portals. A superficial infection does not extend into the joint and can usually be treated with antibiotics alone. If the knee joint itself becomes infected, this is a serious complication and will require antibiotics and possibly another surgical procedure to drain the infection.

Equipment Failure

Many of the instruments used by the surgeon to perform knee arthroscopy are small and fragile. These instruments can be broken resulting in a piece of the instrument floating inside of the knee joint. The broken piece is usually easily located and removed, but this may cause the operation to last longer than planned. There is usually no damage to the knee joint due to the breakage.

Different types of surgical devices (screws, pins, and suture anchors) are used to hold tissue in place during and after arthroscopy. These devices can cause problems. If one breaks, the free-floating piece may hurt other parts inside the knee joint, particularly the articular cartilage. The end of the tissue anchor may poke too far through tissue and the point may rub and irritate nearby tissues. A second surgery may be needed to remove the device or fix problems with these devices.

Slow Recovery

Not everyone gets quickly back to routine activities after knee arthroscopy. Because the arthroscope allows surgeons to use smaller incisions than in the past, many patients mistakenly believe that less surgery was necessary. This is not always true. The arthroscope allows surgeons to do a great deal of reconstructive surgery inside the knee without making large incisions. How fast you recover from knee arthroscopy depends on what type of surgery was done inside your knee. Simple problems that require simple procedures using the arthroscope generally get better faster. Patients with extensive damage to the knee ligaments or articular cartilage tend to require more complex and extensive surgical procedures. These more extensive reconstructions take longer to heal and have a slower recovery. You should discuss this with your surgeon and make sure that you have realistic expectations of what to expect following arthroscopic knee surgery.

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

Knee arthroscopy is usually done on an outpatient basis meaning that patients go home the same day as the surgery. More complex ligament reconstructions that require larger incisions and surgery that alters bone may require a short stay in the hospital to control pain more aggressively and monitor the situation more carefully. You may also begin physical therapy while in the hospital.

The portals are covered with surgical strips, the larger incisions may have been repaired with either surgical staples or sutures and the knee may be wrapped in an elastic bandage (Ace wrap). Crutches are commonly used after knee arthroscopy. They may only be needed for one to two days after a simple procedure.

Patients who have had more complex reconstructive surgery may need to wear a knee brace for several weeks. The brace helps to protect the healing tissue inside the knee joint. You may be allowed to remove the brace at times during the day to do gentle range-of-motion exercises and bathe.

Follow your surgeon’s instructions about how much weight to place on your foot while standing or walking. Avoid doing too much, too quickly. You may be instructed to use a cold pack on the knee and to keep your leg elevated and supported.

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

Your rehabilitation will depend on the type of surgery required. You may not need formal physical therapy after simple procedures such as a partial meniscectomy. Some patients may simply do exercises as part of a home program after some simple instructions.

Many surgeons have patients take part in formal physical therapy after any type of knee arthroscopy procedure. Generally speaking, the more complex the surgery the more involved and prolonged your rehabilitation program will be. The first few physical therapy treatments are designed to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery. Physical therapists will also work with patients to make sure they are putting only a safe amount of weight on the affected leg.

Today, the arthroscope is used to perform quite complicated major reconstructive surgery using very small incisions. Remember, just because you have small incisions on the outside, there may be a great deal of healing tissue on the inside of the knee joint. If you have had major reconstructive surgery, you should expect full recovery to take several months. The physical therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control and improve the range of motion and strength of your knee. When you are well under way, regular visits to your therapist’s office will end. The therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.

Pes Anserine Bursitis of the Knee

A Patient’s Guide to Pes Anserine (Goosefoot) Bursitis

Introduction

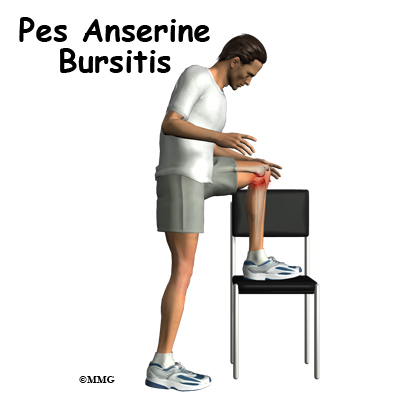

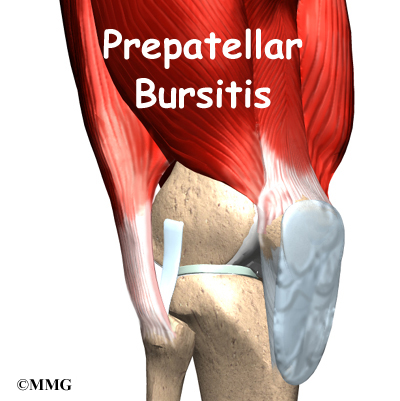

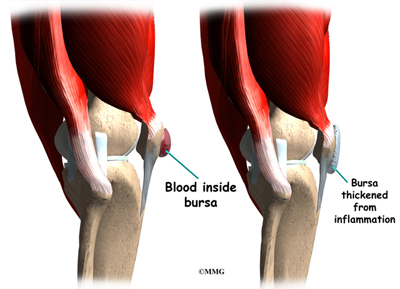

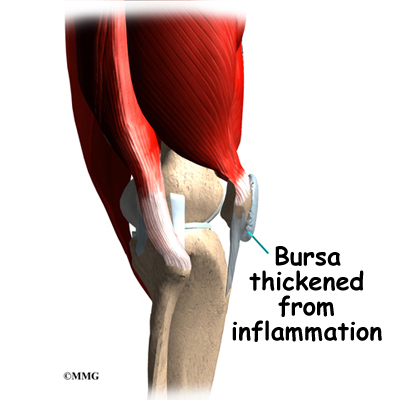

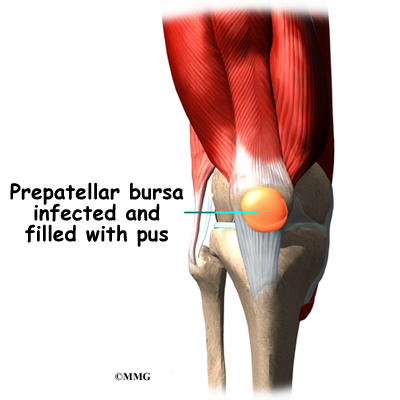

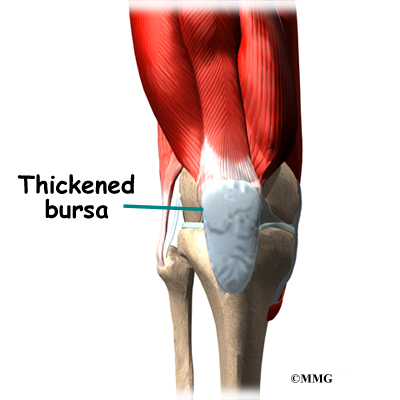

Bursitis of the knee occurs when constant friction on the bursa causes inflammation. The bursa is a small sac that cushions the bone from tendons that rub over the bone. Bursae can also protect other tendons as tissues glide over one another. Bursae can become inflamed and irritated causing pain and tenderness.

This guide will help you understand

- what part of the knee is affected

- what causes this condition

- how doctors diagnose this condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the body are involved?

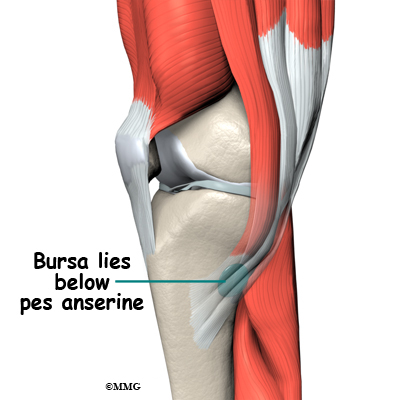

The pes anserine bursa is the main area affected by this condition. The pes anserine bursa is a small lubricating sac between the tibia (shinbone) and the hamstring muscle. The hamstring muscle is located along the back of the thigh.

There are three tendons of the hamstring: the semitendinosus, semimembranosus, and the biceps femoris. The semitendinosus wraps around from the back of the leg to the front. It inserts into the medial surface of the tibia and deep connective tissue of the lower leg. Medial refers to the inside of the knee or the side closest to the other knee.

Just above the insertion of the semitendinosus tendon is the gracilis tendon. The gracilis muscle adducts or moves the leg toward the body. The semitendinosus tendon is also just behind the attachment of the sartorius muscle. The sartorius muscle bends and externally rotates the hip. Together, these three tendons splay out on the tibia and look like a goosefoot. This area is called the pes anserine or pes anserinus.

The pes anserine bursa provides a buffer or lubricant for motion that occurs between these three tendons and the medial collateral ligament (MCL). The MCL is underneath the semitendinosus tendon.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Causes

What causes this problem?

Overuse of the hamstrings, especially in athletes with tight hamstrings is a common cause of goosefoot. Runners are affected most often. Improper training, sudden increases in distance run, and running up hills can contribute to this condition.

It can also be caused by trauma such as a direct blow to this part of the knee. A contusion to this area results in an increased release of synovial fluid in the lining of the bursa. The bursa then becomes inflamed and tender or painful.

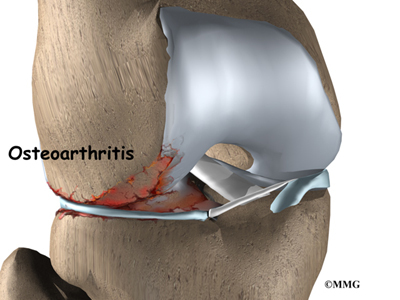

Anyone with osteoarthritis of the knee is also at increased risk for this condition. And alignment of the lower extremity can be a risk factor for some individuals. A turned out position of the knee or tibia, genu valgum (knock knees), or a flatfoot position can lead to pes anserine bursitis.

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

The patient often points to the pes anserine as the area of pain or tenderness. The pes anserine is located about two to three inches below the joint on the inside of the knee. This is referred to as the anterior knee or proximedia tibia. Proximedia is short for proximal and medial. This term refers to the front inside edge of the tibia.

Some patients also have pain in the center of the tibia. This occurs when other structures are also damaged such as the meniscus (cartilage). The pain is made worse by exercise, climbing stairs, or activities that cause resistance to any of these tendons.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose this problem?

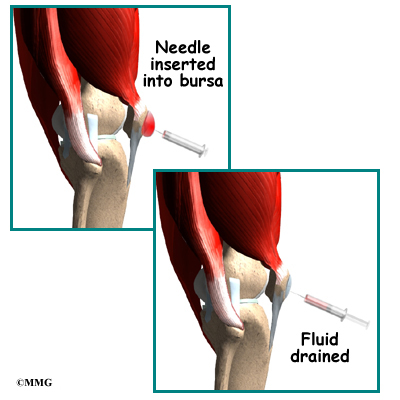

A history and clinical exam will help the physician differentiate pes anserine bursitis from other causes of anterior knee pain, such as patellofemoral syndrome or arthritis. An X-ray is needed to rule out a stress fracture or arthritis. An MRI may be needed to look for damage to other areas of the medial compartment of the knee. Fluid from the bursa may be removed and tested if infection is suspected.

The examiner will also assess hamstring tightness. This is done in the supine position (lying on your back). Your hip is flexed (bent) to 90 degrees. The knee is straightened as far as possible. The amount of knee flexion is an indication of how tight the hamstrings are. If you can straighten your knee all the way in this position, then you do not have tight hamstrings.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

The goal of treatment for overuse injuries such as pes anserine bursitis is to reduce the strain on the injured tissues. Stopping the activity that brings on or aggravates the symptoms is the first step toward pain reduction.

Bedrest is not required but it may be necessary to modify some of your activities. This will give time for the bursa to quiet down and for the pain to subside. Patients are advised to avoid stairs, climbing, or other irritating activities. This type of approach is called relative rest

Ice and antiinflammatory medications can be used in the early, inflammatory phase. The ice is applied three or four times each day for 20 minutes at a time. Ice cubes wrapped in a thin layer of toweling or a bag of frozen vegetables applied to the area works well.

Athletes are often instructed by their physical therapist or athletic trainer to perform an ice massage. A cup of water is frozen in a Styrofoam container. The top edge of the container is torn away leaving a one-inch surface of ice that can be rubbed around the area. The Styrofoam protects the hand of the person holding the cup while applying the ice massage. The pes anserine area is massaged with the ice for 10 minutes or until the skin is numb. Caution is advised to avoid frostbite.

Over-the-counter nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Ibuprofen may be advised. In some cases, the physician will prescribe stronger NSAIDs. Your physical therapist can also use a process called iontophoresis. Using an electric charge, an antiinflammatory drug can be pushed through the skin to the inflamed area. This method is called transdermal drug delivery. Iontophoresis puts a higher concentration of the drug directly in the area compared to taking medications by mouth. This process does not deliver as much drug as a local injection.

Improving flexibility is a key part of the prevention and treatment of this condition. Hamstring stretching is performed at least twice a day for a minimum of 30 seconds each time. Holding the stretch for a full minute has been proven even more effective. Some patients must perform this stretch more often, even once an hour if necessary.

Do not bounce during the stretch. Hold the position at a point of feeling the stretch but not so far that it is painful or uncomfortable. Deep breathing can help ease the discomfort. Try to stretch a little more as you breathe out.

Quadriceps strengthening is also important. This is especially true if there are other areas of the knee affected. The quadriceps muscle along the front of the thigh extends the knee and helps balance the pull of the hamstrings.

A special type of exercise program called closed kinetic chain (CKC) is performed for six to eight weeks to assist with quadriceps strengthening. The CKC may include single-knee dips, squats and leg presses. Resisted leg-pulls using elastic tubing are also included. The exercise program is prescribed by a physical therapist and gradually progressed during the eight-week session.

If these measures are not enough, your physician may inject the bursa with a solution of lidocaine (an anesthetic or numbing agent) combined with a steroid (an antiinflammatory). The steroid injection can be diagnostic as well. If the symptoms are improved, it is assumed the problem was coming from the pes anserine bursa.

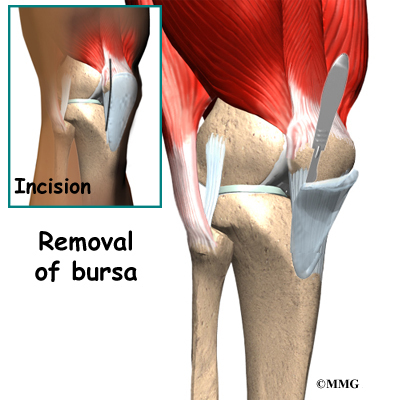

Surgery

Surgery is rarely needed for pes anserine bursitis. The bursa may be removed if chronic infection cannot be cleared up with antibiotics.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Pes anserine bursitis is considered a self-limiting condition. This means it usually responds well to treatment and will resolve without further intervention. Athletes may have to continue a program of hamstring stretching and CKC quadriceps strengthening on a regular basis.

Athletes may return to sports or play when the symptoms are gone and are no longer aggravated by certain activities. Protective gear for the knee may be needed for those individuals who participate in contact sports. During the rehab process, activity level and duration are gradually increased. If the symptoms don’t come back, the athlete can continue to progress to full participation in all activities.

After Surgery

If the bursa is removed, you follow the same steps of rehab and recovery outlined under Nonsurgical Treatment.

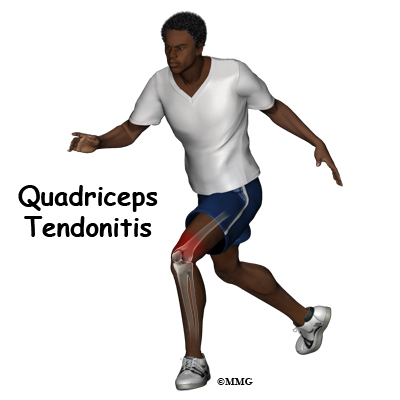

Patellar Tendonitis

A Patient’s Guide to Patellar Tendonitis

Introduction

Alignment or overuse problems of the knee structures can lead to strain, irritation, and/or injury. This produces pain, weakness, and swelling of the knee joint. Patellar tendonitis (also known as jumper’s knee) is a common overuse condition associated with running, repeated jumping and landing, and kicking.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the knee are involved

- how the problem develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the knee are involved?

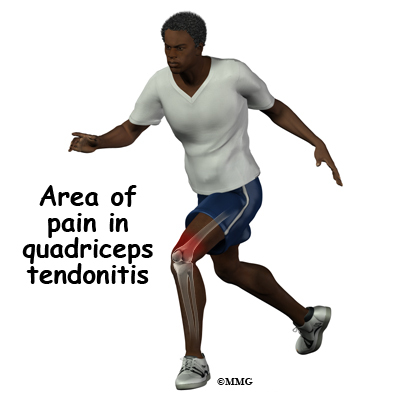

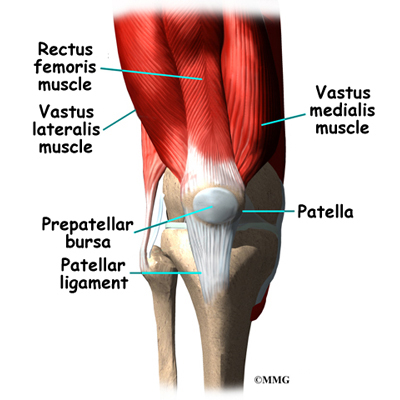

The patella (kneecap) is the moveable bone on the front of the knee. This unique bone is wrapped inside a tendon that connects the large muscles on the front of the thigh, the quadriceps muscles, to the tibia lower leg bone.

The large quadriceps muscle ends in a tendon that inserts into the tibial tubercle, a bony bump at the top of the tibia (shin bone) just below the patella. The tendon together with the patella is called the quadriceps mechanism. Though we think of it as a single device, the quadriceps mechanism has two separate tendons, the quadriceps tendon on top of the patella and the infrapatellar tendon or patellar tendon below the patella.

Tightening up the quadriceps muscles places a pull on the tendons of the quadriceps mechanism. This action causes the knee to straighten. The patella acts like a fulcrum to increase the force of the quadriceps muscles.

The long bones of the femur and the tibia act as level arms, placing force or load on the knee joint and surrounding soft tissues. The amount of load can be quite significant. For example, the joint reaction forces of the lower extremity (including the knee) are two to three times the body weight during walking and up to five times the body weight when running.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Causes

What causes this problem?

Patellar tendonitis occurs most often as a result of stresses placed on the supporting structures of the knee. Running, jumping, and repetitive knee flexion into extension (e.g., rising from a deep squat) contribute to this condition. Overuse injuries from sports activities is the most common cause but anyone can be affected, even those who do not participate in sports or recreational activities.

There are extrinsic (outside) factors that are linked with overuse tendon injuries of the knee. These include inappropriate footwear, training errors (frequency, intensity, duration), and surface or ground (hard surface, cement) being used for the sport or event (such as running). Training errors are summed up by the rule of “toos”. This refers to training too much, too far, too fast, or too long. Advancing the training schedule forward too quickly is a major cause of patellar tendonitis.

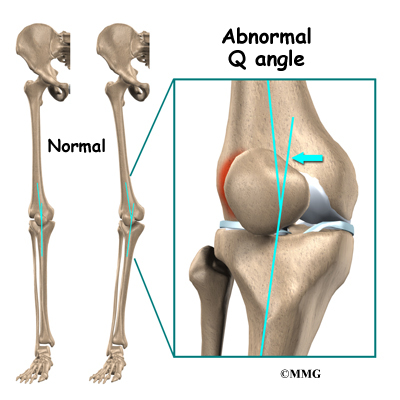

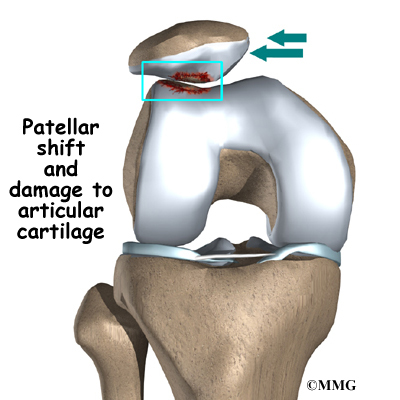

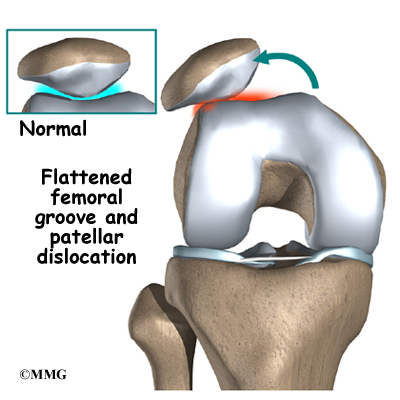

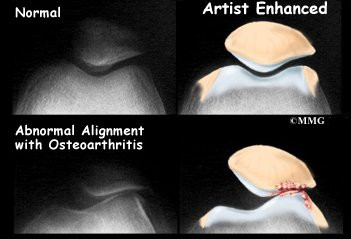

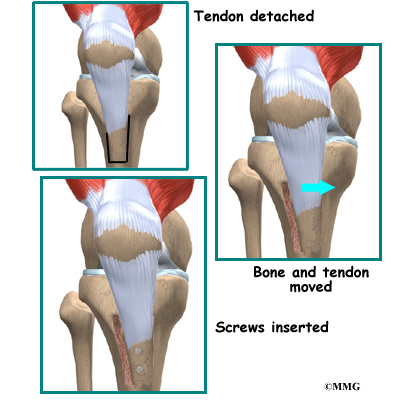

Intrinsic (internal) factors such as age, flexibility, and joint laxity are also important. Malalignment of the foot, ankle, and leg can play a key role in tendonitis. Flat foot position, tracking abnormalities of the patella, rotation of the tibia called tibial torsion, and a leg length difference can create increased and often uneven load on the quadriceps mechanism.

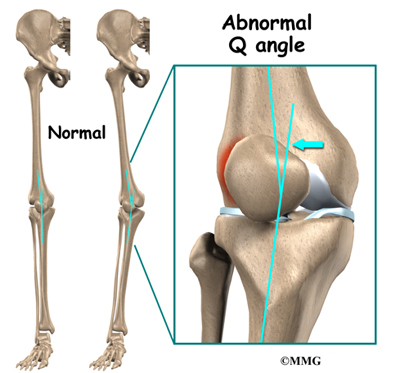

An increased Q-angle or femoral anteversion are two common types of malalignment that contribute to patellar tendonitis. The Q-angle is the angle formed by the patellar tendon and the axis of pull of the quadriceps muscle. This angle varies between the sexes. It is larger in women compared to men. The normal angle is usually less than 15 degrees. Angles more than 15 degrees create more of a pull on the tendon, creating painful inflammation.

Any muscle imbalance of the lower extremity (from the hip down to the toes) can impact the quadriceps muscle and affect the joint. Individuals who are overweight may have added issues with load and muscle imbalance leading to patellar tendonitis.

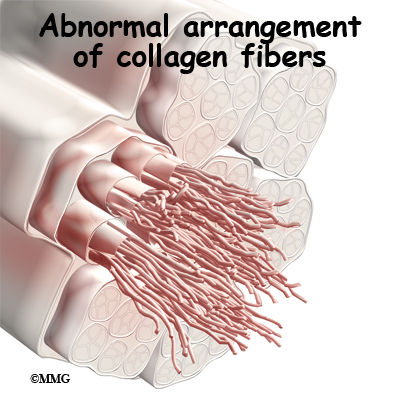

Strength of the patellar tendon is in direct proportion to the number, size, and orientation of the collagen fibers that make up the tendon. Overuse is simply a mismatch between load or stress on the tendon and the ability of that tendon to distribute the force. If the forces placed on the tendon are greater than the strength of the structure, then injury can occur. Repeated microtrauma at the muscle tendon junction may overcome the tendon’s ability to heal itself. Tissue breakdown occurs triggering an inflammatory response that leads to tendonitis.

Chronic tendonitis is really a problem called tendonosis. Inflammation is not present. Instead, degeneration and/or scarring of the tendon has developed. Chronic tendon injuries are much more common in older athletes (30 to 50 years old).

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

Pain from patellar tendonitis is felt just below the patella. The pain is most noticeable when you move your knee or try to kneel. The more you move your knee, the more tenderness develops in the area of the tendon attachment below the kneecap.

There may be swelling in and around the patellar tendon. It may be tender or very sensitive to touch. You may feel a sense of warmth or burning pain. The pain can be mild or in some cases the pain can be severe enough to keep the runner from running or other athletes from participating in their sport. The pain is worse when rising from a deep squat position. Resisted quadriceps contraction with the knee straight also aggravates the condition.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the problem?

Diagnosis begins with a complete history of your knee problem followed by an examination of the knee, including the patella. There is usually tenderness with palpation of the inflamed tissues at the insertion of the tendon into the bone. The knee will be assessed for range of motion, strength, flexibility and joint stability.

The physician will look for intrinsic and extrinsic factors affecting the knee (especially sudden changes in training habits). Potential problems with lower extremity alignment are identified. The doctor will also check the hamstrings for telltale weakness and tightness.

X-rays may be ordered on the initial visit to your doctor. An X-ray can show fractures of the tibia or patella but X-rays do not show soft tissue injuries. In these cases, other tests, such as ultrasonography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), may be suggested. Ultrasound uses sound waves to detect tendon tears. MRIs use magnetic waves rather than X-rays to show the soft tissues of the body. This machine creates pictures that look like slices of the knee. Usually, this test is done to look for injuries, such as tears in the quadriceps. This test does not require any needles or special dye and is painless.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

The initial treatment for acute patellar tendonitis begins by decreasing the inflammation in the knee. Your physician may suggest relative rest and anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin or ibuprofen, especially when the problem is coming from overuse. Acetaminophen (Tylenol®) may be used for pain control if you can’t take anti-inflammatory medications for any reason.

Relative rest is a term used to describe a process of rest-to-recovery based on the severity of symptoms. Pain at rest means strict rest and a short time of immobilization in a splint or brace is required. When pain is no longer present at rest, then a gradual increase in activity is allowed so long as the resting pain doesn’t come back.

Physical therapy can help in the early stages by decreasing pain and inflammation. Your physical therapist may use ice massage, electrical stimulation, and ultrasound to limit pain and control (but not completely prevent) swelling. Some amount of inflammatory response is needed for a good healing response.

The therapist will prescribe stretching and strengthening exercises to correct any muscle imbalances. Eccentric muscle strength training helps prevent and treat injuries that occur when high stresses are placed on the tendon during closed kinetic chain activities. Eccentric contractions occur as the contracted muscle lengthens. Closed kinetic chain activities means the foot is planted on the floor as the knee bends or straightens.

A specific protocol of exercises may be needed when rehabilitating this injury. After a five-minute warm up period, stretches are performed. Next, in a standing position, the patient bends the knees and drops quickly into a squatting position, and then stands up again quickly. The goal is to do this exercise as quickly as possible. Eventually sandbags are added to the shoulders to increase the load on the tendon. All exercises must be done without pain.

Researchers have also discovered that patellar tendonitis responds to a concentric-eccentric program of exercises for the anterior tibialis muscle. The anterior tibialis muscle is located along the front of the lower leg. It is the muscle that helps you dorsiflex the ankle (pull your toes and ankle up toward the face).

You start with your foot in a position of full plantar flexion by rising up on your toes. Now drop down into a position of dorsiflexion. This is a concentric muscle contraction. Resistance of the foot and ankle from full dorsiflexion back into plantar flexion is the eccentric contraction. This exercise is repeated until the anterior tibialis fatigues. As your pain subsides, the program progresses so that eventually, you will just be doing the eccentric activities.

Flexibility exercises are often designed for the thigh and calf muscles. Specific exercises are used to maximize control and strength of the quadriceps muscles. You will be shown how to ease back into jumping or running sports using good training techniques. Off-season strength training of the legs, particularly the quadriceps muscles is advised.

Bracing or taping the patella can help you do exercises and activities with less pain. Most braces for patellofemoral problems are made of soft fabric, such as cloth or neoprene. You slide them onto your knee like a sleeve. A small buttress pads the side of the patella to keep it lined up within the groove of the femur. An alternative to bracing is to tape the patella in place. The therapist applies and adjusts the tape over the knee to help realign the patella. The idea is that by bracing or taping the knee, the patella stays in better alignment within the femoral groove. This in turn is thought to improve the pull of the quadriceps muscle so that the patella stays lined up in the groove. Patients report less pain and improved function with these forms of treatment.

Therapists also design special shoe inserts, called orthotics, to improve knee alignment and function of the patella. Proper footwear for your sport is important. The therapist will advise you in this area.

Prevention of future injuries through patient education is a key component of the treatment program. This is true whether conservative care or surgical intervention is required. Modification of intrinsic and extrinsic risk factors is essential.