Hand

Swan Neck Deformity of the Finger

A Patient’s Guide to Swan Neck Deformity of the Finger

Introduction

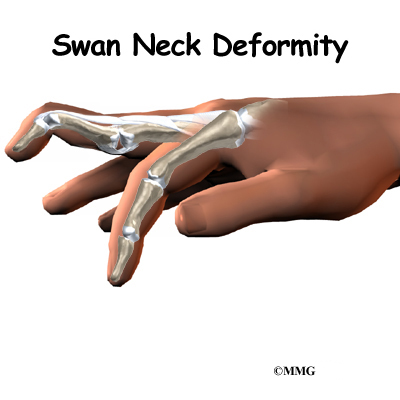

Normal finger position and movement occur from the balanced actions of many important structures. Ligaments support the finger joints. Muscles hold and move the fingers. Tendons help control the fine motion of each finger joint. Disease or injury can disturb the balance in these structures, altering normal finger alignment and function. The result may be a crooked finger, such as a swan neck deformity of the finger.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the finger are affected

- what causes swan neck deformity

- how the problem is treated

- what to expect from treatment

Anatomy

What parts of the finger are involved?

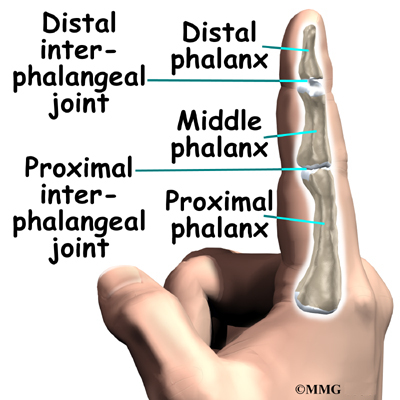

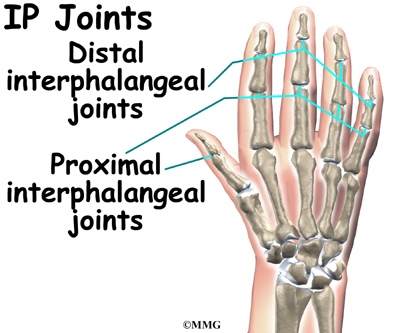

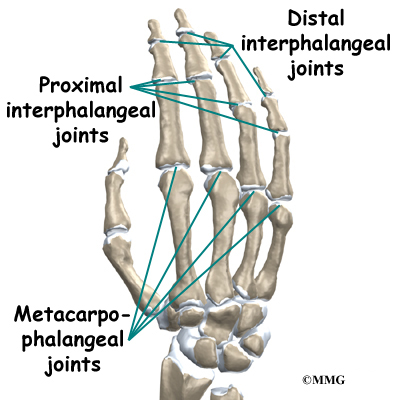

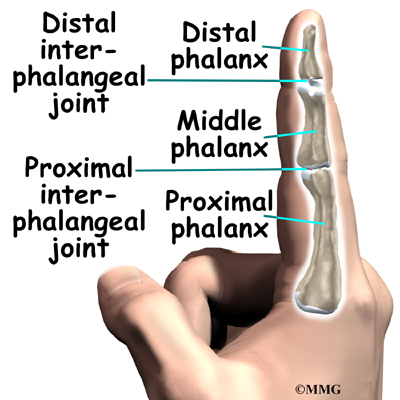

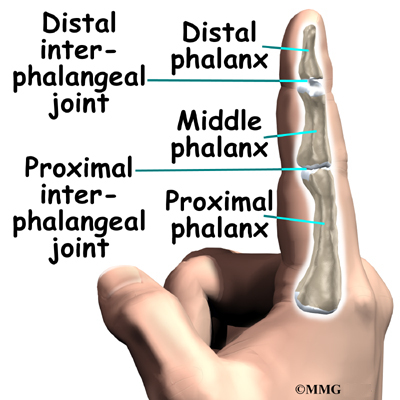

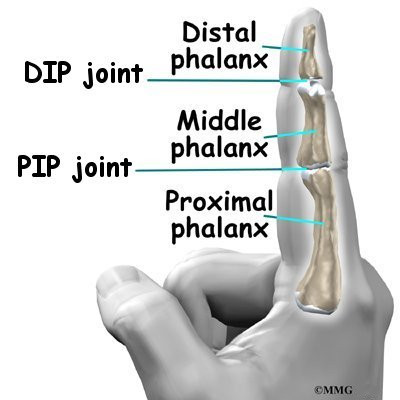

The fingers are actually made up of three bones, called phalanges. The three phalanges in each finger are separated by two joints, called interphalangeal joints (IP joints). The joint near the end of the finger is called the distal IP joint (DIP joint). (Distal means further away.) The proximal IP joint (PIP joint) is the middle joint between the main knuckle and the DIP joint. (Proximal means closer in.) The IP joints of the fingers work like hinge joints when you bend and straighten your hand.

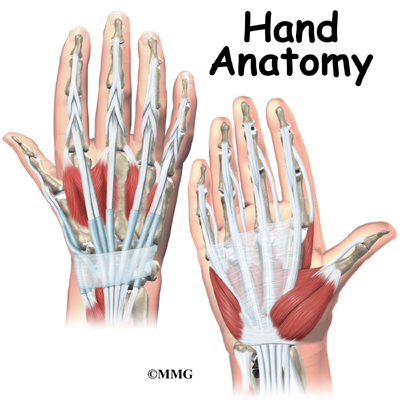

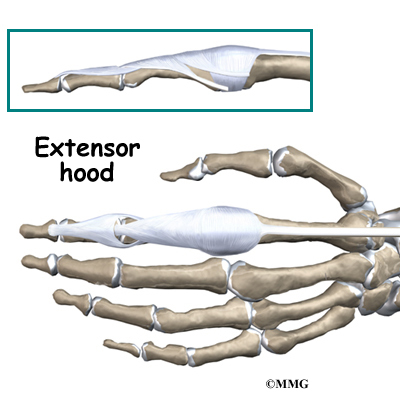

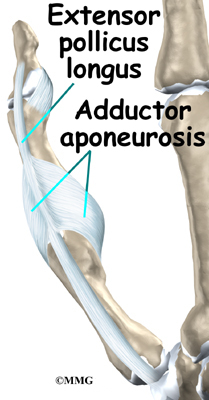

The tendons that allow each finger joint to straighten are called the extensor tendons. The extensor tendons of the fingers begin as muscles that arise from the backside of the forearm bones. These muscles travel toward the hand, where they eventually connect to the extensor tendons before crossing over the back of the wrist joint. As they travel into the fingers, the extensor tendons become the extensor hood. The extensor hood flattens out to cover the top of the finger and sends out branches on each side that connect to the bones in the middle and end of the finger. When the extensor muscles contract, they tug on the extensor tendon and straighten the finger.

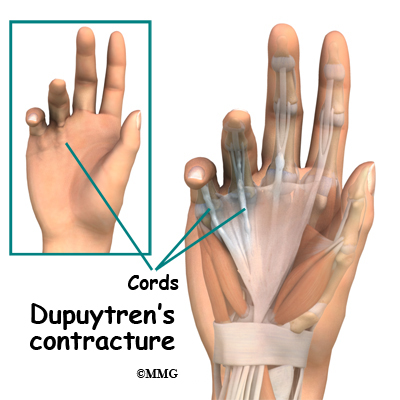

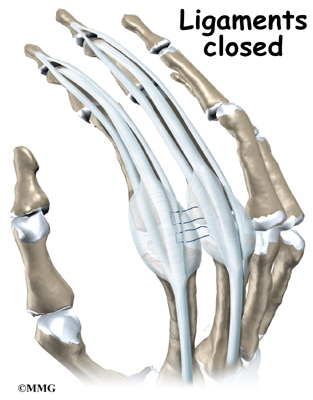

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect bones together. Several small ligaments connect the extensor hood with other tendons that travel into the finger to bend the finger. These connections help balance the motion of the finger so that all the joints of the finger work together, giving a smooth bending and straightening action.

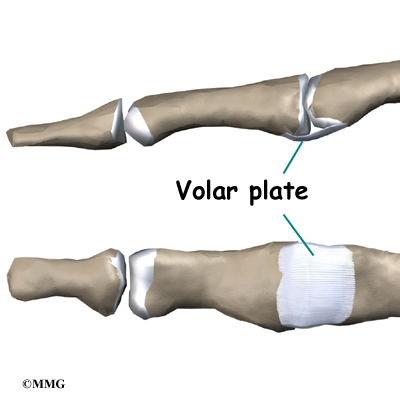

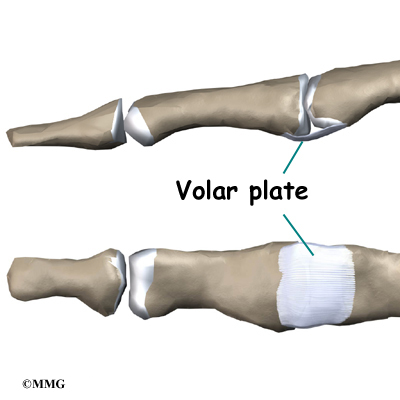

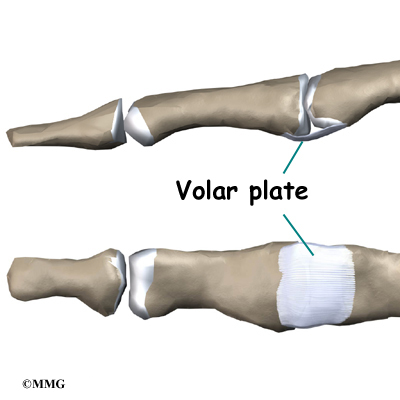

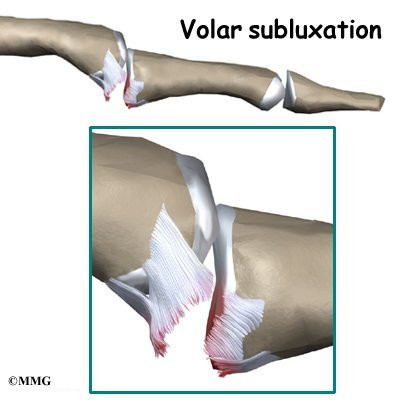

In the PIP joint (the middle joint between the main knuckle and the DIP joint), the strongest ligament is the volar plate. This ligament connects the proximal phalanx to the middle phalanx on the palm side of the joint. The ligament tightens as the joint is straightened and keeps the PIP joint from bending back too far (hyperextending). Swan neck deformity can occur when the volar plate loosens from disease or injury.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

How does this condition occur?

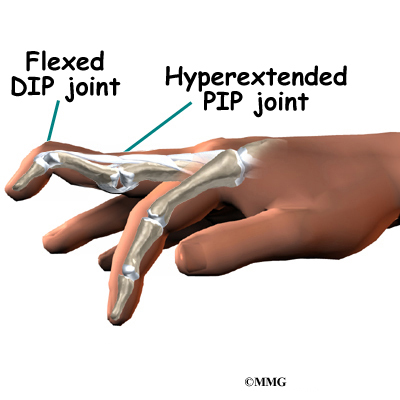

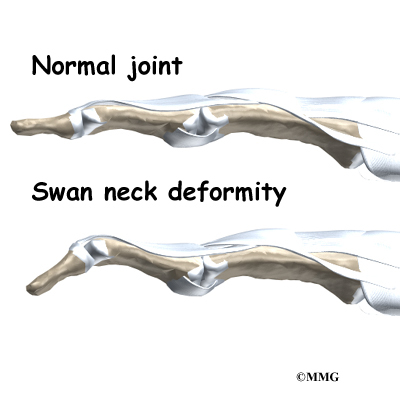

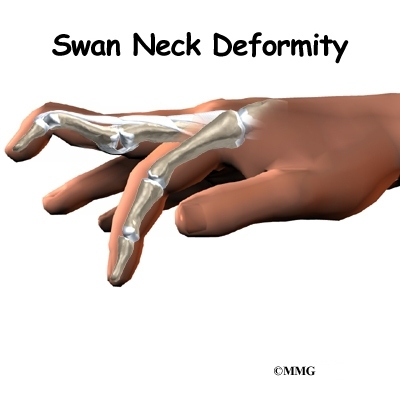

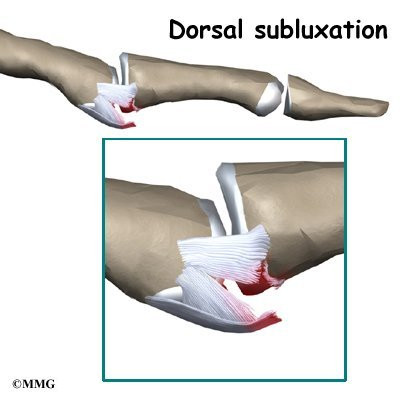

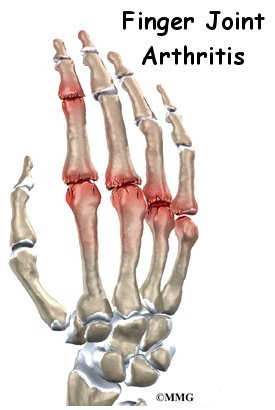

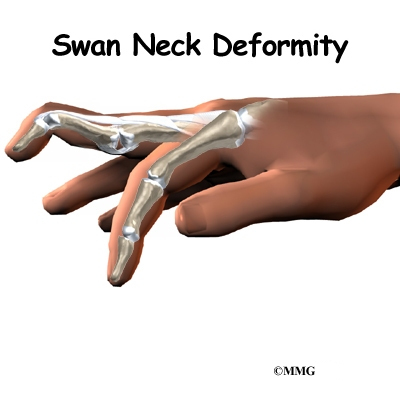

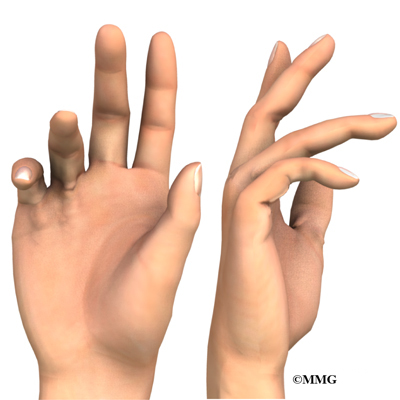

A swan neck deformity describes a finger with a hyperextended PIP joint and a flexed DIP joint.

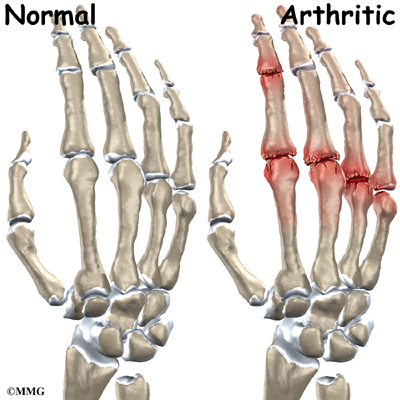

Conditions that loosen the PIP joint and allow it to hyperextend can produce a swan neck deformity of the finger. Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is the most common disease affecting the PIP joint. Chronic inflammation of the PIP joint puts a stretch on the volar plate. (As mentioned earlier, the volar plate is a supportive ligament in front of the PIP joint that normally keeps the PIP joint from hyperextending.) As the volar plate becomes weakened and stretched, the PIP joint becomes loose and begins to easily bend back into hyperextension. The extensor tendon gets out of balance, which allows the DIP joint to get pulled downward into flexion. As the DIP joint flexes and the PIP joint hyperextends, the swan neck deformity occurs.

View animation of of PIP joint hyperextension

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Rheumatoid Arthritis

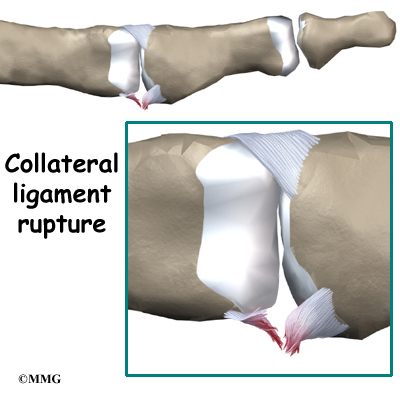

Other conditions that weaken the volar plate can produce a swan neck deformity. The small (intrinsic) muscles of the hand and fingers can tighten up from hand trauma, RA, and various nerve disorders, such as cerebral palsy, Parkinson’s disease, or stroke. The muscle imbalance tends to weaken the volar plate and pull the PIP joint into extension. Weakness in the volar plate can also occur from a finger injury that forces the PIP joint into hyperextension, stretching or rupturing the volar plate. As mentioned, looseness (laxity) in the volar plate can lead to a swan neck deformity.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to PIP Joint Injuries of the Finger

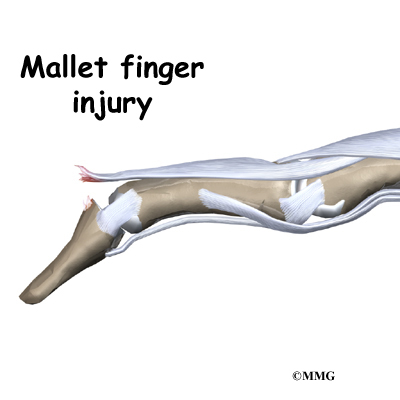

Clearly, PIP joint problems can produce a swan neck deformity. But so can problems that start in the DIP joint at the end of the finger. Injury or disease that disrupts the end of the extensor tendon can cause the DIP joint to droop (flex).

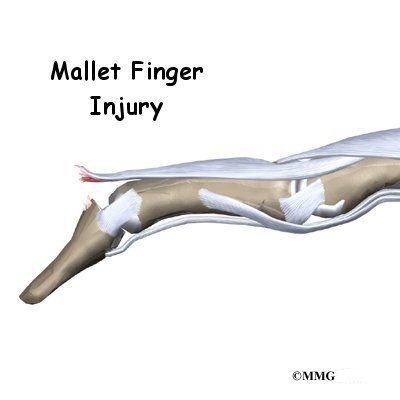

An example from sports is a jammed finger that tears or ruptures the extensor tendon at the end of the finger (distal phalanx). Without treatment, the DIP joint droops and won’t straighten out. This condition is called a mallet finger. The extensor tendon may become imbalanced and begin to pull the PIP joint into hyperextension, forming a swan neck deformity.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Mallet Finger Injuries

Chronic inflammation from RA can also disrupt the very end of the extensor tendon. Inflammation and swelling in the DIP joint stretches and weakens the extensor tendon where it passes over the top of the DIP joint. A mallet deformity occurs in the DIP, followed by hyperextension of the PIP joint. Again, the result is a swan neck deformity.

Symptoms

What do swan neck deformities look and feel like?

Inflammation from injury or disease (such as RA) may cause pain and swelling of the PIP joint. The PIP joint eventually is free to bend back too far into hyperextension. The DIP joint is bent downward into flexion. Eventually, the imbalance leads to the typical shape of the finger with a swan neck deformity.

Diagnosis

What tests will my doctor do?

Usually the diagnosis is evident just from the physical examination. An X-ray may be ordered so the doctor can check the condition of the joint surfaces, examine joint alignment, and see if a fracture is present (as in a traumatic finger injury). No other tests are required normally.

Treatment

What can be done for a swan neck deformity of the finger?

Treatment for swan neck deformity can be nonsurgical or surgical. The approach your doctor uses depends on whether the PIP joint is flexible or stiff.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Successful nonsurgical treatment is based on restoring balance in the structures of the hand and fingers. The PIP joint must be supple (not stiff). Aligning the PIP joint and preventing hyperextension should help restore DIP extension. If it doesn’t, surgery may be needed.

You may require professional rehabilitation. A physical or occupational therapist addresses the imbalances that have formed the swan neck deformity. Stretching, massage, and joint mobilization are used to try and restore finger alignment and function.

A special splint may be used to keep the PIP joint lined up, protect the joint from hyperextending, and still allow the PIP joint to bend. Newer styles are shaped like jewelry rings and are available in stainless steel, sterling silver, or gold. This approach works best for mild cases of swan neck deformity in which the PIP joint is supple.

Splinting and a rigorous therapy program are usually not successful in altering the imbalance responsible for the deformity. However, many hand surgeons will try six weeks with the splint and exercise to improve PIP joint mobility before performing surgery.

Surgery

Soft Tissue Repair

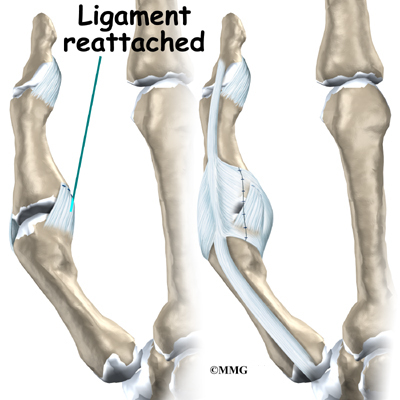

In cases where the balance cannot be restored to a tolerable limit with splinting, surgery may be required to reconstruct and rebalance the structures around the PIP joint. The surgeon releases, aligns, and balances the soft tissues around the PIP joint. The surgery may involve the skin (dermadesis), the tendons (tenodesis), or the ligaments (mobilization or reconstruction).

Surgery to repair the soft tissues that are contributing to a swan neck deformity carries a relatively high risk of failure to achieve completely normal functioning of the finger. All of the repair and reconstruction procedures are dependant on a well designed and rigorous exercise program following the surgery. A physical or occupational therapist will work closely with you during your recovery.

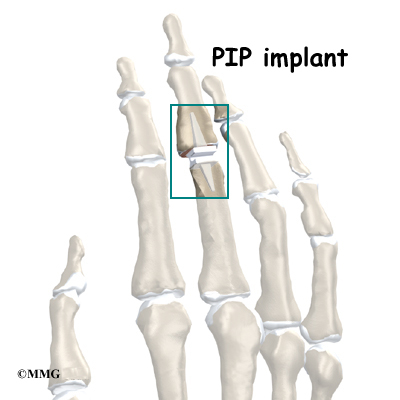

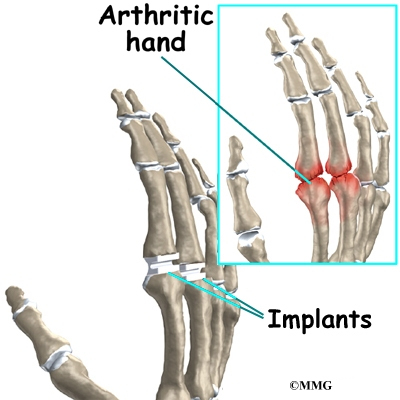

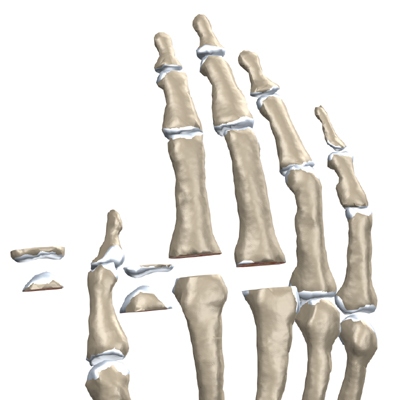

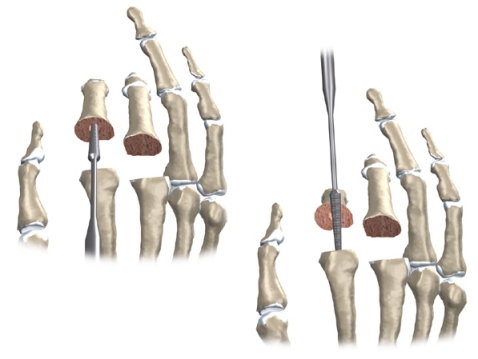

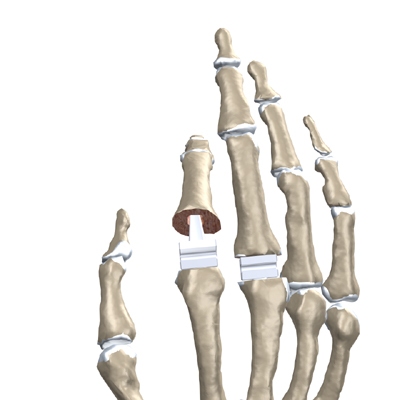

PIP Joint Arthroplasty

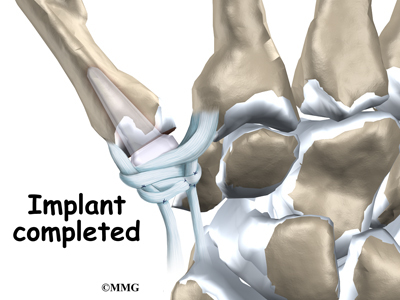

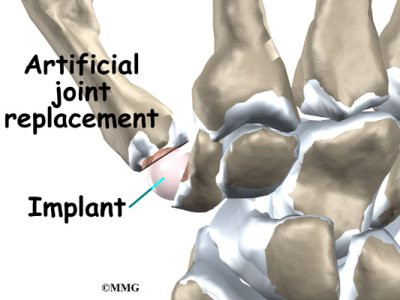

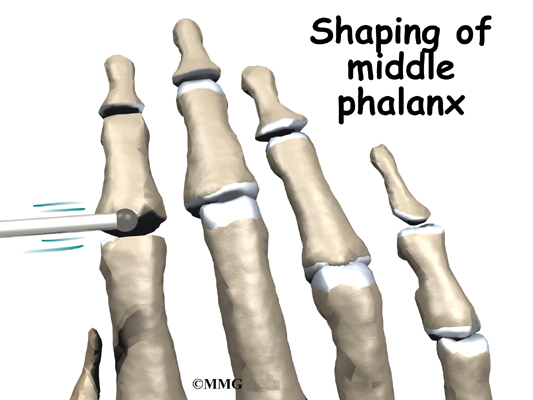

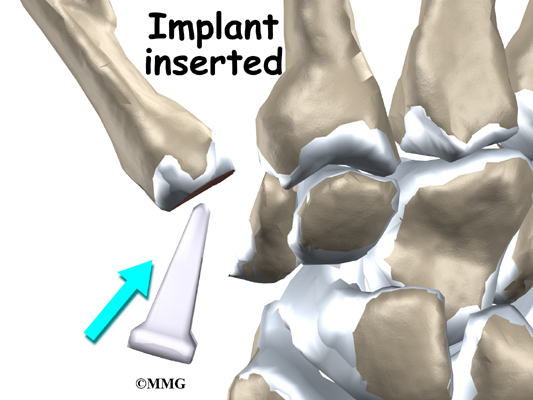

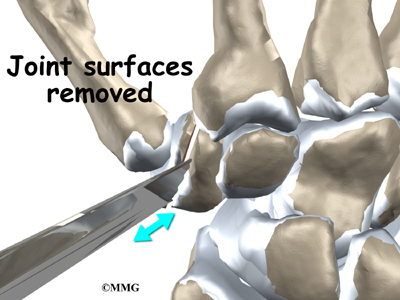

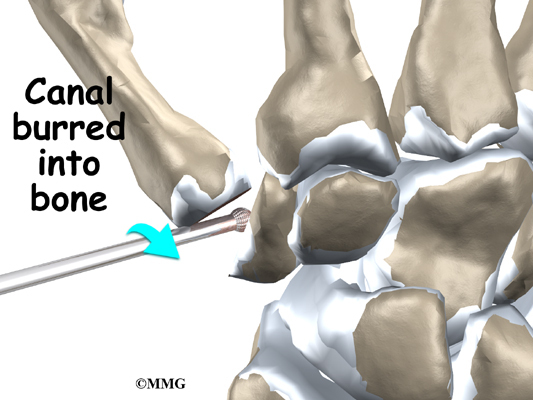

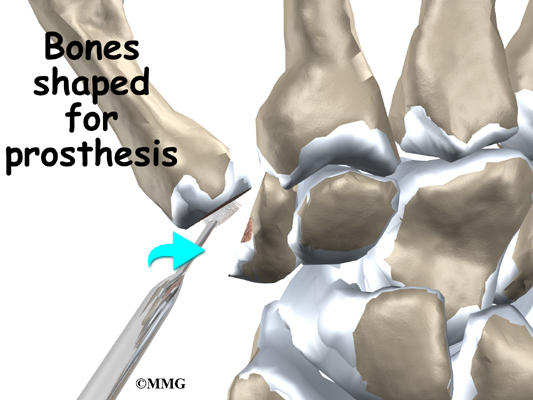

Swan neck deformity with a stiff PIP joint sometimes requires replacement of the PIP joint, called arthroplasty. The surgeon works from the back surface (dorsum) of the finger joint. Both surfaces of the PIP joint are removed to make room for the new implant. With the new joint in place, the surgeon balances the soft tissues around the joint to ensure that the new joint can easily bend and straighten.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Finger

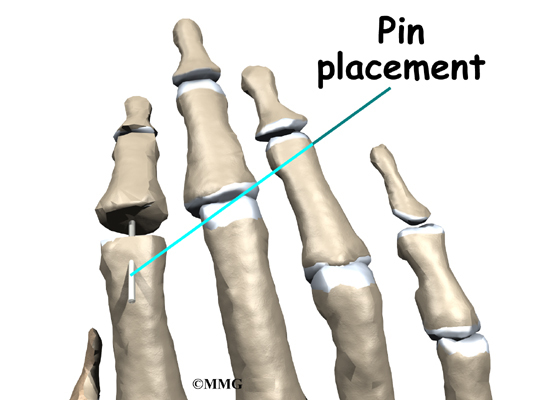

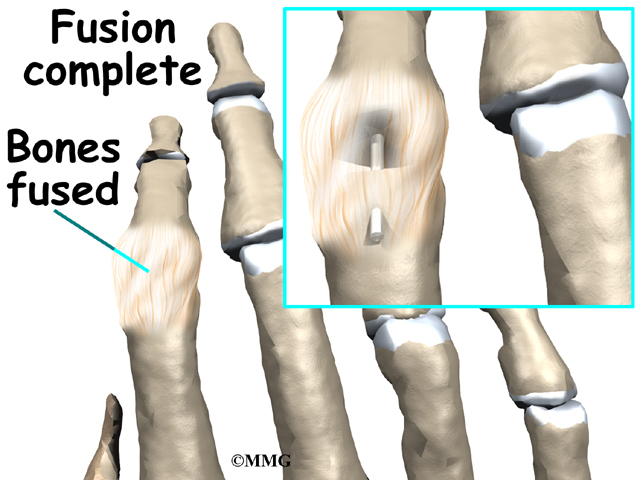

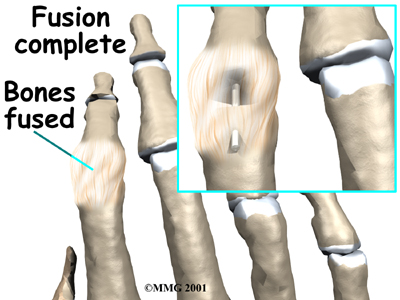

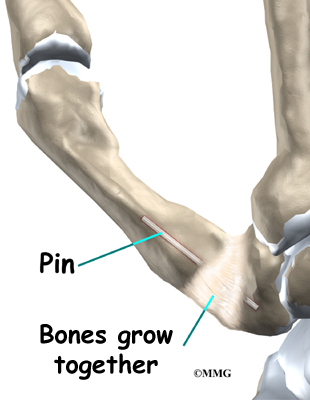

Finger Joint Fusion

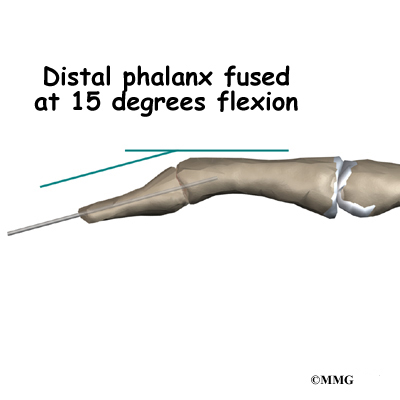

When RA produces a mallet deformity of the DIP joint and the PIP joint is supple, surgeons may consider fusing the DIP joint. Joint fusion is a procedure that binds the two joint surfaces of the finger together, keeping them from moving. Fusing the two joint surfaces together eases pain, makes the joint stable, and helps prevent additional joint deformity.

If past treatments, including surgery, do not stop inflammation or deformity in the PIP joint, fusion of the PIP joint may be recommended. The PIP joint is usually fused in a bent position, between 25 and 45 degrees.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Finger Fusion Surgery

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

The goal of nonsurgical treatment is to get the finger joints, tendons, and muscles in balance. If nonsurgical treatment is successful, you may see improvement in eight to 12 weeks. Your doctor may have you work with a physical or occupational therapist during this time.

Your therapist will work with you to obtain and use your finger splint. Special forms of stretching may help reduce tightness in the intrinsic muscles of the hand and fingers. Strengthening exercises can help with alignment and function of the hand and fingers.

After Surgery

You’ll wear a splint or brace after surgery. A protective finger splint holds and protects the joint and is used for at least three weeks after surgery. Physical or occupational therapy treatments usually start three to six weeks after surgery.

You will likely need to attend therapy sessions for three to four months, and you should expect full recovery to take up to six months. The first few therapy treatments will focus on controlling the pain and swelling from surgery. Then you’ll begin gentle range-of-motion exercise. Strengthening exercises are started eight to 10 weeks after surgery. You’ll learn ways to grip and support items in order to do your tasks safely and with the least amount of stress on your finger joint. As with any surgery, you need to avoid doing too much, too quickly.

Eventually, you’ll begin doing exercises designed to get your hand and fingers working in ways that are similar to your work tasks and daily activities. Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don’t put too much stress on your finger joint. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

Your therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control, improve your strength and range of motion, and regain fine motor abilities with your hand and finger. When you are well under way, regular visits to your therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.

Hand Anatomy

A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Introduction

Few structures of the human anatomy are as unique as the hand. The hand needs to be mobile in order to position the fingers and thumb. Adequate strength forms the basis for normal hand function. The hand also must be coordinated to perform fine motor tasks with precision. The structures that form and move the hand require proper alignment and control in order for normal hand function to occur.

In addition to reading this article, be sure to watch our Hand Anatomy Animated Tutorial Video.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the hand

- how those parts work together

Important Structures

The important structures of the hand can be divided into several categories. These include

- bones and joints

- ligaments and tendons

- muscles

- nerves

- blood vessels

The front, or palm-side, of the hand is referred to as the palmar side. The back of the hand is called the dorsal side.

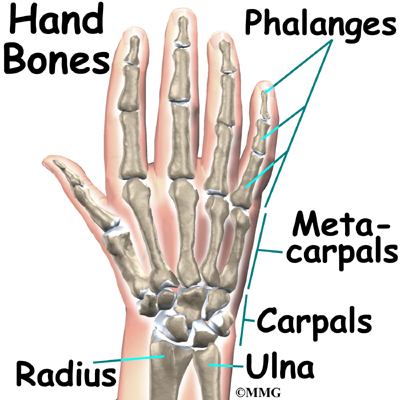

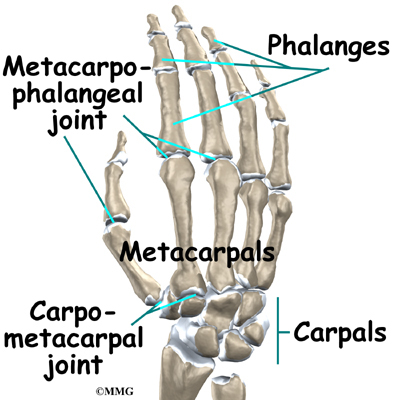

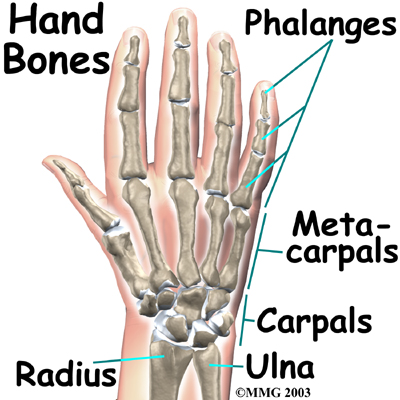

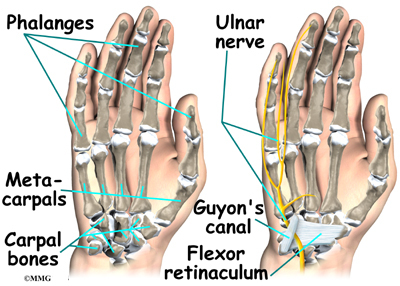

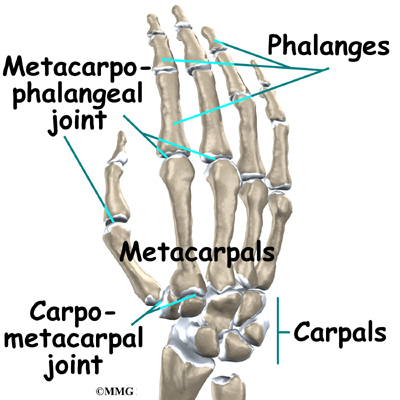

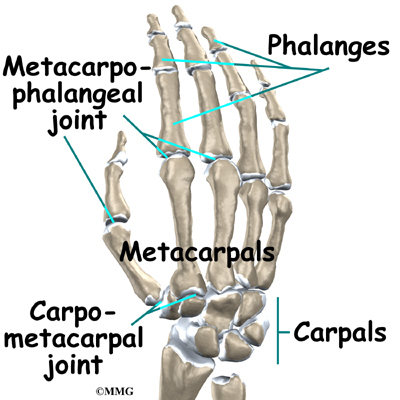

Bones and Joints

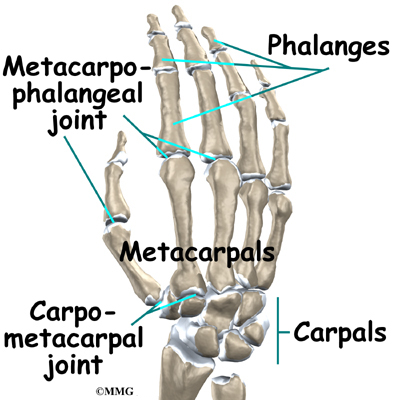

There are 27 bones within the wrist and hand. The wrist itself contains eight small bones, called carpals. The carpals join with the two forearm bones, the radius and ulna, forming the wrist joint. Further into the palm, the carpals connect to the metacarpals. There are five metacarpals forming the palm of the hand. One metacarpal connects to each finger and thumb. Small bone shafts called phalanges line up to form each finger and thumb.

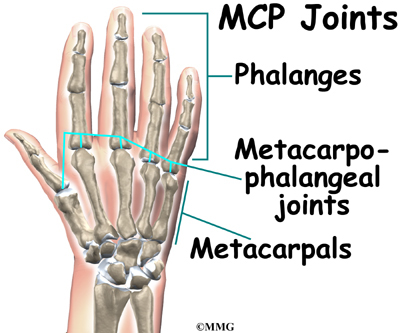

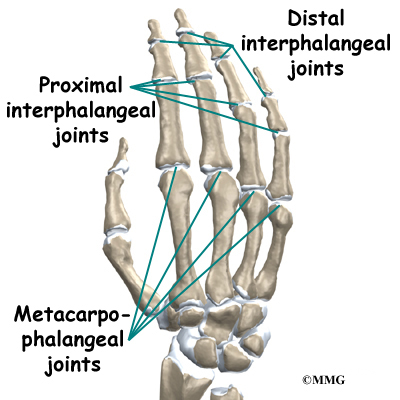

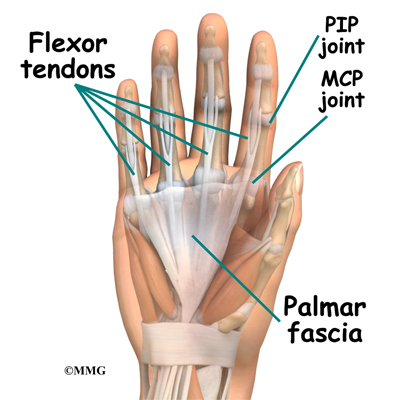

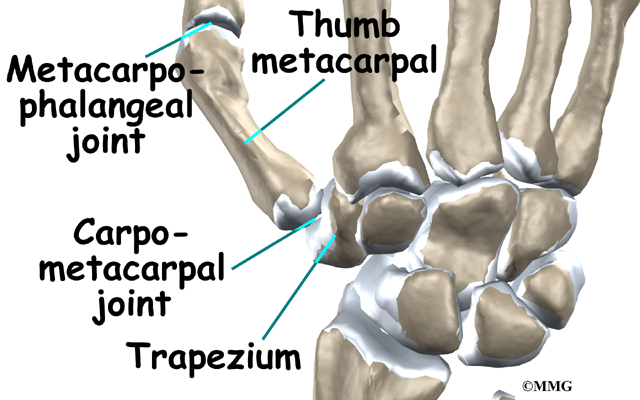

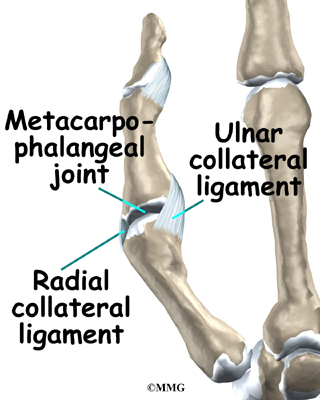

The main knuckle joints are formed by the connections of the phalanges to the metacarpals. These joints are called the metacarpophalangeal joints (MCP joints). The MCP joints work like a hinge when you bend and straighten your fingers and thumb.

The three phalanges in each finger are separated by two joints, called interphalangeal joints (IP joints). The one closest to the MCP joint (knuckle) is called the proximal IP joint (PIP joint). The joint near the end of the finger is called the distal IP joint (DIP joint). The thumb only has one IP joint between the two thumb phalanges. The IP joints of the digits also work like hinges when you bend and straighten your fingers and thumb.

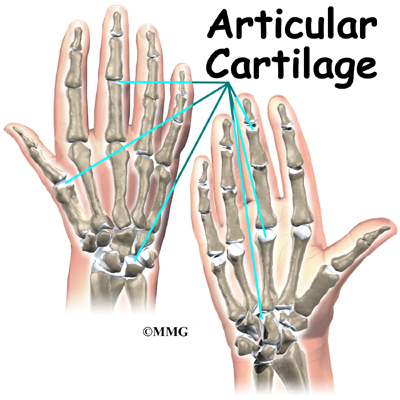

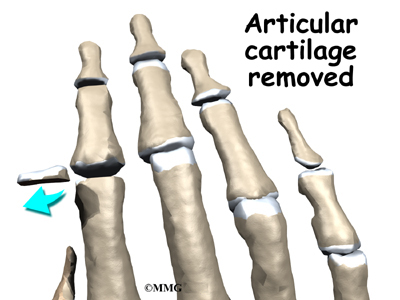

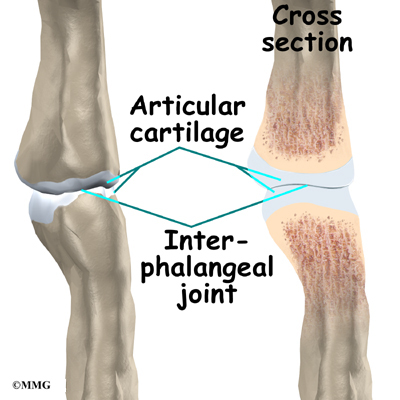

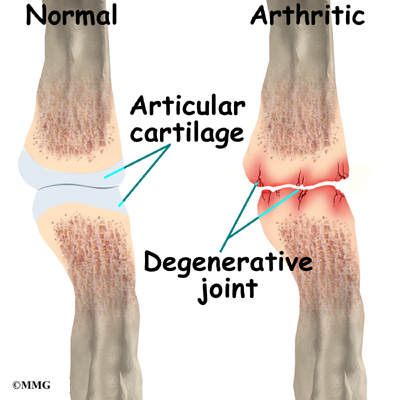

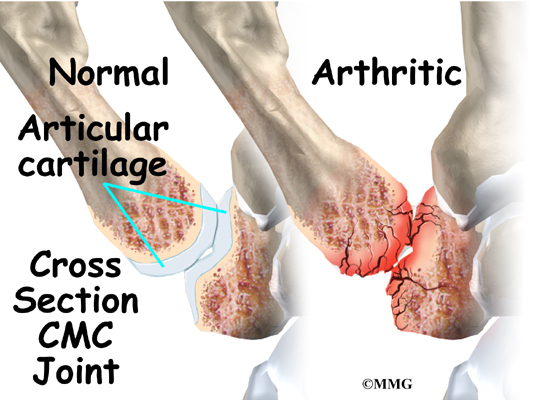

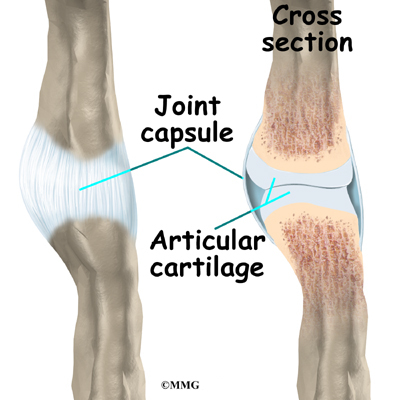

The joints of the hand, fingers, and thumb are covered on the ends with articular cartilage. This white, shiny material has a rubbery consistency. The function of articular cartilage is to absorb shock and provide an extremely smooth surface to

facilitate motion. There is articular cartilage essentially everywhere that two bony surfaces move against one another, or articulate.

Ligaments and Tendons

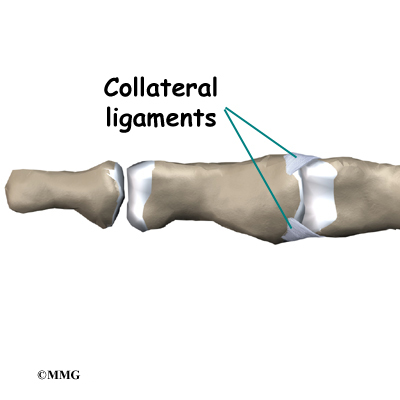

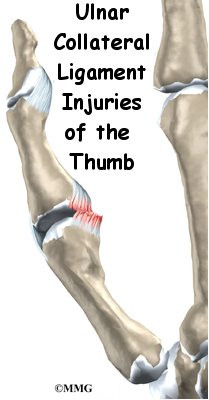

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect bones together. Two important structures, called collateral ligaments, are found on either side of each finger and thumb joint. The function of the collateral ligaments is to prevent abnormal sideways bending of each joint.

In the PIP joint (the middle joint between the main knuckle and the DIP joint), the strongest ligament is the volar plate. This ligament connects the proximal phalanx to the middle phalanx on the palm side of the joint. The ligament tightens as the joint is straightened and keeps the PIP joint from bending back too far (hyperextending). Finger deformities can occur when the volar plate loosens from disease or injury.

The tendons that allow each finger joint to straighten are called the extensor tendons. The extensor tendons of the fingers begin as muscles that arise from the backside of the forearm bones. These muscles travel towards the hand, where they eventually connect to the extensor tendons before crossing over the back of the wrist joint. As they travel into the fingers, the extensor tendons become the extensor hood. The extensor hood flattens out to cover the top of the finger and sends out branches on each side that connect to the bones in the middle and end of the finger.

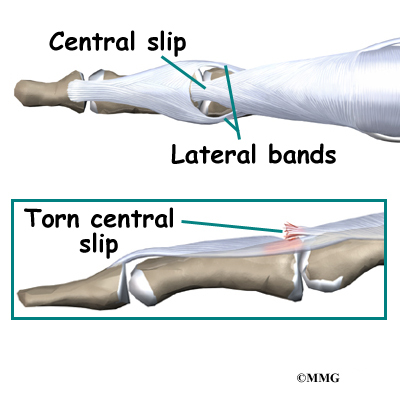

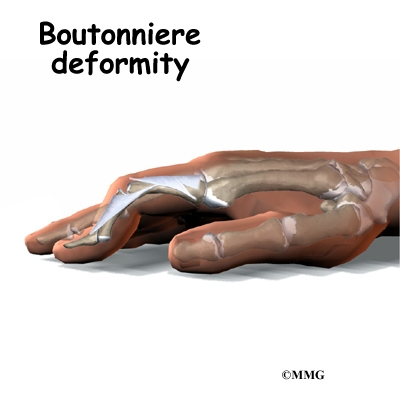

The place where the extensor tendon attaches to the middle phalanx is called the central slip. When the extensor muscles contract, they tug on the extensor tendon and straighten the finger. Problems occur when the central slip is damaged, as can happen with a tear.

Muscles

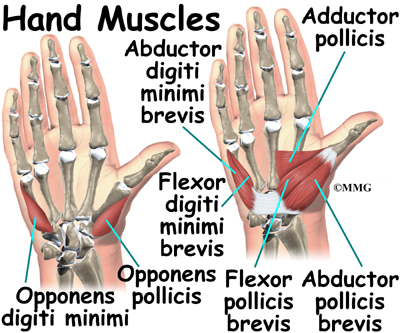

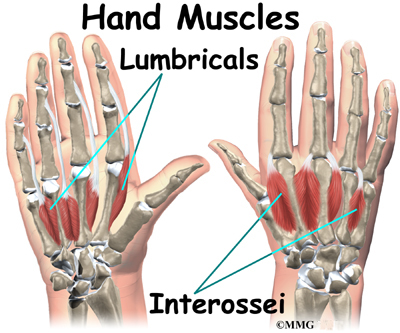

Many of the muscles that control the hand start at the elbow or forearm. They run down the forearm and cross the wrist and hand. Some control only the bending or straightening of the wrist. Others influence motion of the fingers or thumb. Many of these muscles help position and hold the wrist and hand while the thumb and fingers grip or perform fine motor actions.

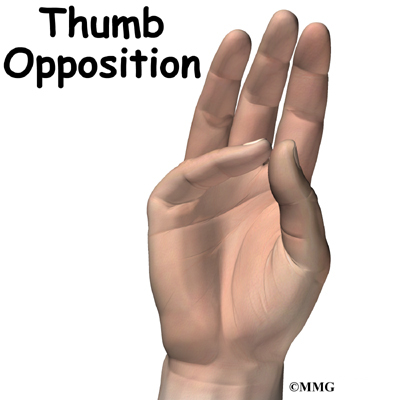

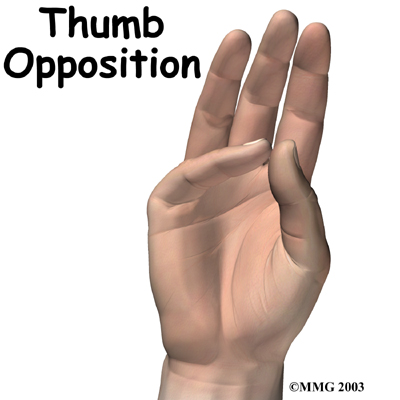

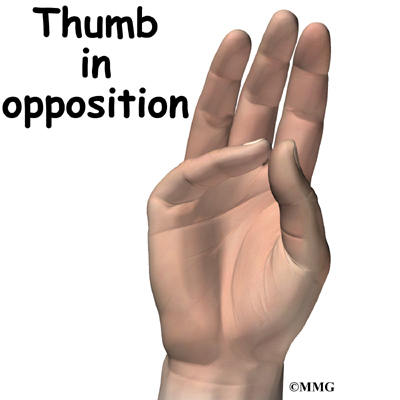

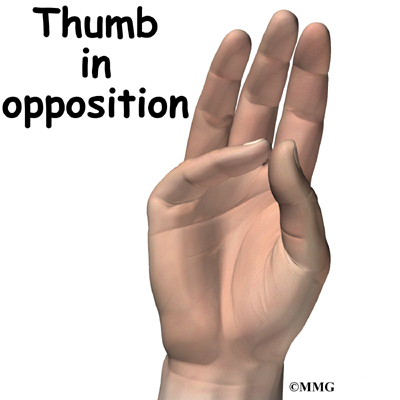

Most of the small muscles that work the thumb and pinky finger start on the carpal bones. These muscles connect in ways that allow the hand to grip and hold. Two muscles allow the thumb to move across the palm of the hand, an important function called thumb opposition.

The smallest muscles that originate in the wrist and hand are called the intrinsic muscles. The intrinsic muscles guide the fine motions of the fingers by getting the fingers positioned and holding them steady during hand activities.

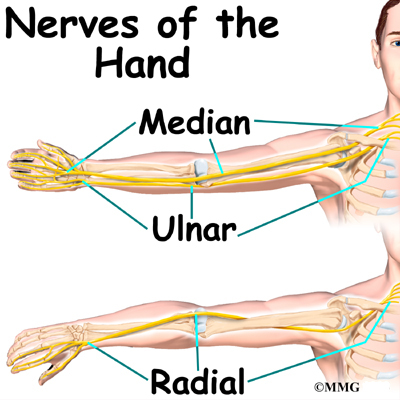

Nerves

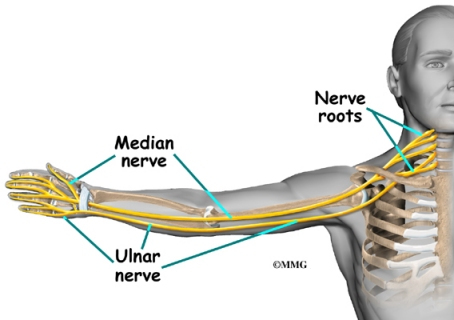

All of the nerves that travel to the hand and fingers begin together at the shoulder: the radial nerve, the median nerve, and the ulnar nerve. These nerves carry signals from the brain to the muscles that move the arm, hand, fingers, and thumb. The nerves also carry signals back to the brain about sensations such as touch, pain, and temperature.

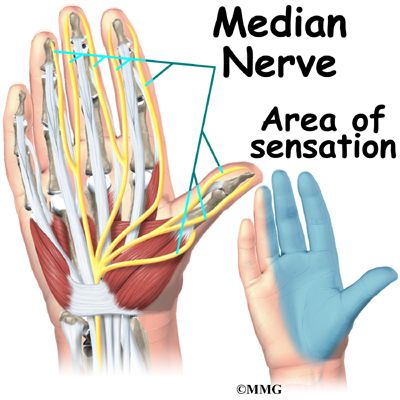

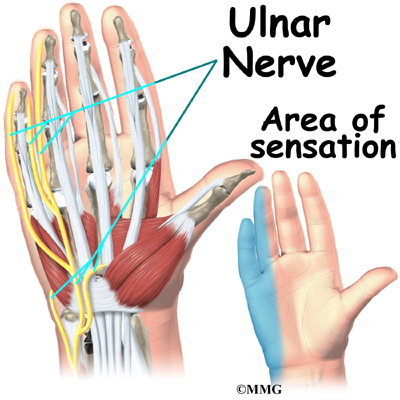

The radial nerve runs along the thumb-side edge of the forearm. It wraps around the end of the radius bone toward the back of the hand. It gives sensation to the back of the hand from the thumb to the third finger. It also supplies the back of the thumb and just beyond the main knuckle of the back surface of the ring and middle fingers.

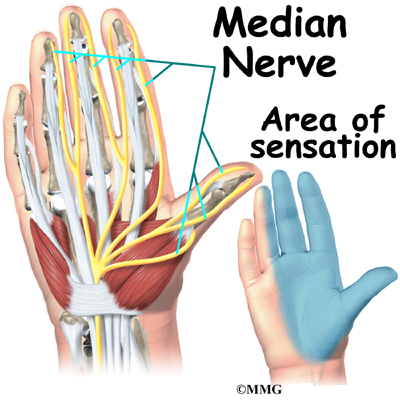

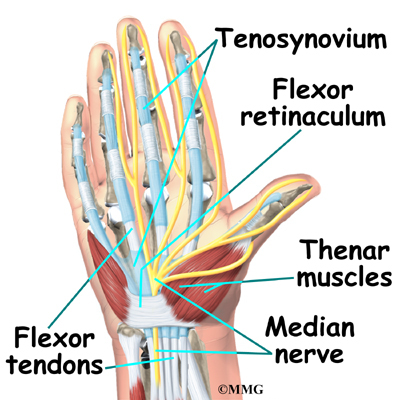

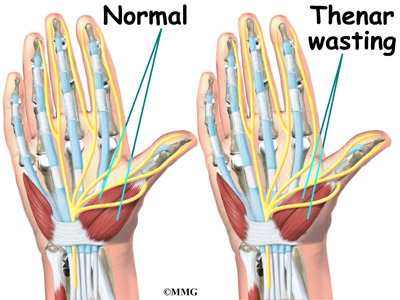

The median nerve travels through a tunnel within the wrist called the carpal tunnel. This nerve gives sensation to the thumb, index finger, long finger, and half of the ring finger. It also sends a nerve branch to control the thenar muscles of the thumb. The thenar muscles help move the thumb and let you touch the pad of the thumb to the tips each of each finger on the same hand, a motion called opposition.

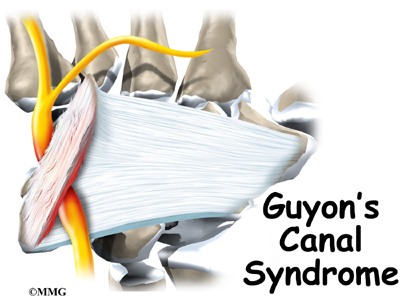

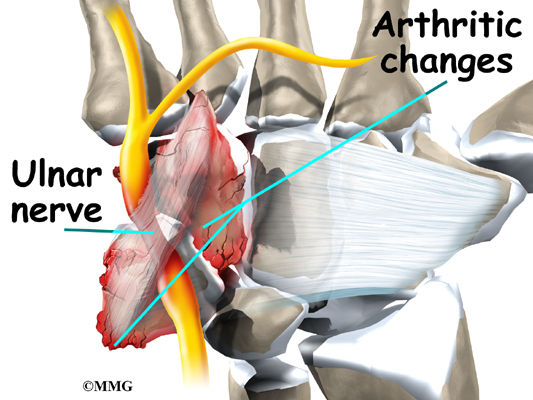

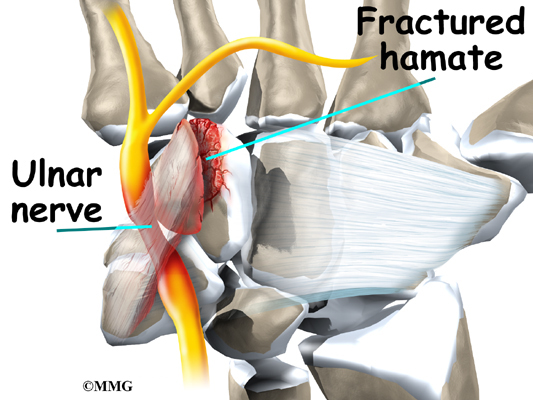

The ulnar nerve travels through a separate tunnel, called Guyon’s canal. This tunnel is formed by two carpal bones, the pisiform and hamate, and the ligament that connects them. After passing through the canal, the ulnar nerve branches out to supply feeling to the little finger and half the ring finger. Branches of this nerve also supply the small muscles in the palm and the muscle that pulls the thumb toward the palm.

The nerves that travel to the hand are subject to problems. Constant bending and straightening of the wrist and fingers can lead to irritation or pressure on the nerves within their tunnels and cause problems such as pain, numbness, and weakness in the hand, fingers, and thumb.

Blood Vessels

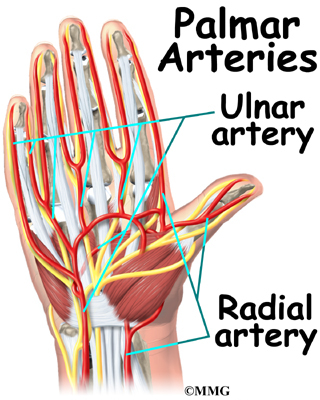

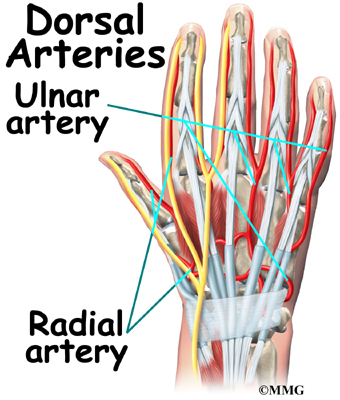

Traveling along with the nerves are the large vessels that supply the hand with blood. The largest artery is the radial artery that travels across the front of the wrist, closest to the thumb. The radial artery is where the pulse is taken in the wrist. The ulnar artery runs next to the ulnar nerve through Guyon’s canal (mentioned earlier). The ulnar and radial arteries arch together within the palm of the hand, supplying the front of the hand, fingers, and thumb. Other arteries travel across the back of the wrist to supply the back of the hand, fingers, and thumb.

Summary

The hand is formed of numerous structures that have an important role in normal hand function. Conditions that change the way these structures work can greatly impact whether the hand functions normally. When our hands are free of problems, it’s easy to take the complex anatomy of the hand for granted.

Open Carpal Tunnel Release

A Patient’s Guide to Open Carpal Tunnel Release

Introduction

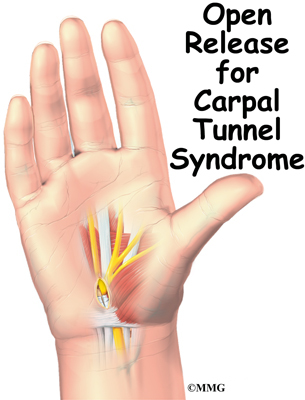

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) occurs when the median nerve is squeezed as it courses through the wrist. The passageway through the wrist, called the carpal tunnel, is formed by the small wrist bones (carpals) on one side and a ligament on the other. In an open release for CTS, the surgeon makes an incision on the front of the wrist and hand in order to cut the ligament. The goal is to relieve pressure on the median nerve.

This guide will help you understand

- what part of the wrist and hand are treated during surgery

- how surgeons perform the operation

- what to expect before and after the procedure

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Anatomy

What part of the wrist is treated during surgery?

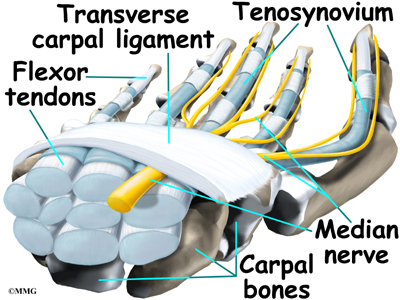

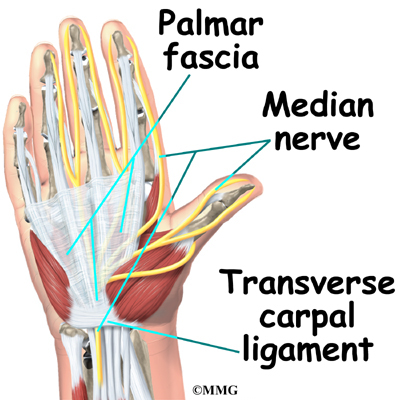

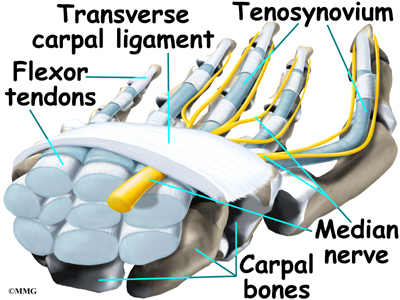

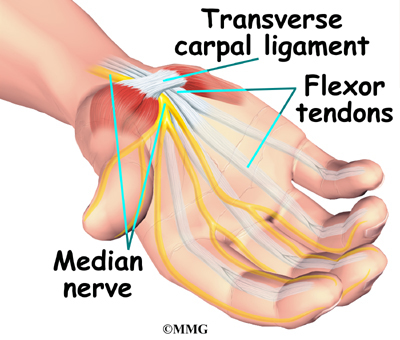

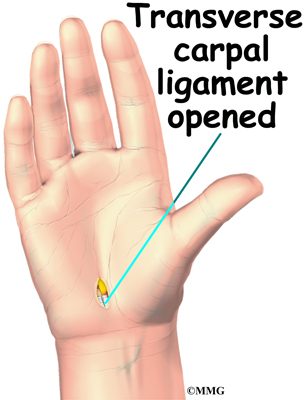

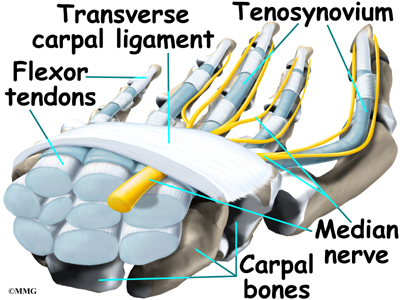

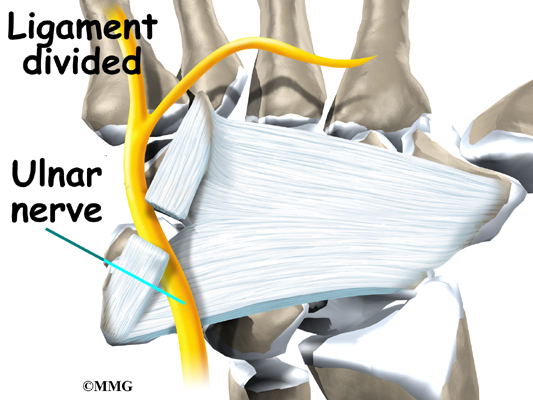

The carpal tunnel is an opening through the wrist into the hand that is formed by the carpal bones of the wrist on the bottom and the transverse carpal ligament on the top. The transverse carpal ligament is at the base of the wrist and crosses from one side of the wrist to the other. (Transverse means across.) It is sometimes referred to as the carpal ligament.

The opening formed by the carpal bones and the carpal ligament is the carpal tunnel. The median nerve passes through the carpal tunnel into the hand. It gives sensation to the thumb, index finger, long finger, and half of the ring finger. It also sends a nerve branch to control the thenar muscles of the thumb.

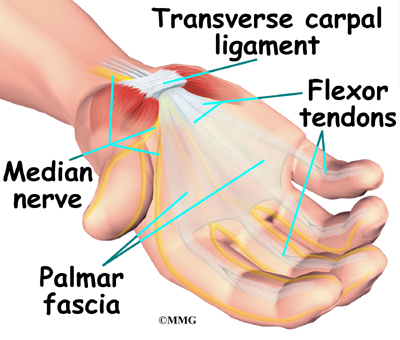

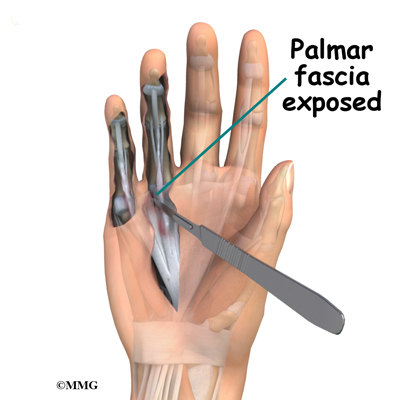

The median nerve rests on top of the flexor tendons, just below the carpal ligament. Between the skin and the carpal ligament is a thin sheet of connective tissue called the palmar fascia.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to achieve?

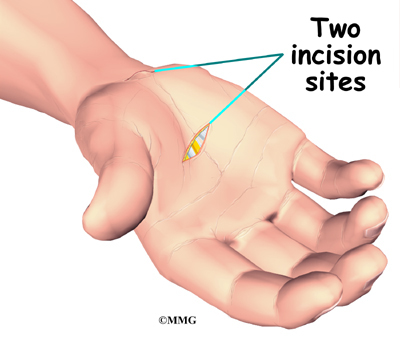

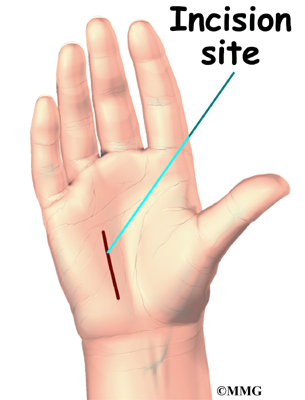

The surgery releases the carpal ligament, taking pressure off the median nerve. The open procedure for releasing the carpal ligament involves a sizeable wrist incision, usually about two inches long. By creating a large incision, the surgeon is able to clearly see the wrist structures and to carefully do the operation.

Preparation

What should I do to prepare for surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery must be made jointly by you and your surgeon. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before. This surgery can usually be done as an outpatient procedure, meaning you can leave the hospital the same day.

Procedure

Open release for CTS is occasionally done using a general anesthetic (one that puts you to sleep). More often, it is done using a regional anesthetic. A regional anesthetic blocks the nerves going to only a portion of the body. Injections of medications similar to lidocaine are used to block the nerves for several hours. This type of anesthesia could be an axillary block (only the arm is asleep) or a wrist block (only the hand is asleep). The surgery can also be performed by simply injecting lidocaine around the area of the incision.

Once you have anesthesia, your surgeon will make sure the skin of your palm is free of infection by cleaning the skin with a germ-killing solution.

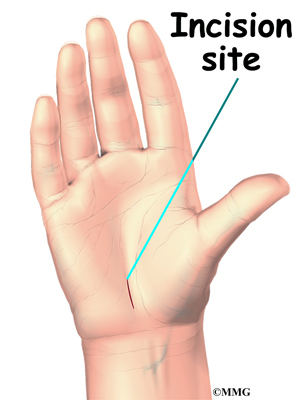

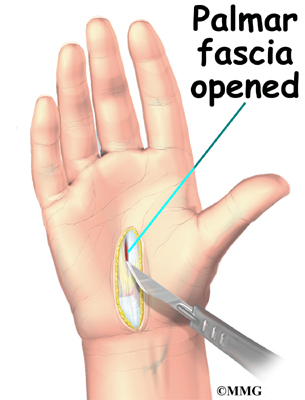

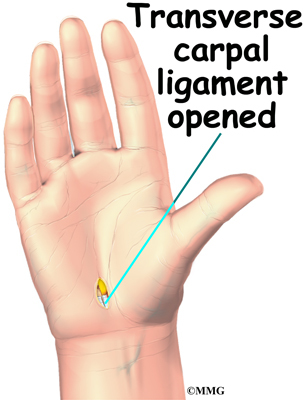

A small incision is made in the palm of the hand, usually about one inch long. In some severe cases, a slightly longer incision is extended into the forearm. The incision makes the palmar fascia visible. This is a sheet of connective tissue in the palm and forearm right under the skin. The surgeon makes an incision through this material and exposes the carpal ligament.

View animation of palmar fascia exposed

View animation of ligament exposed

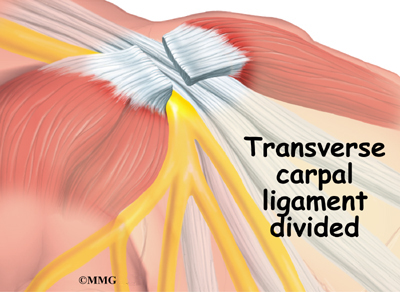

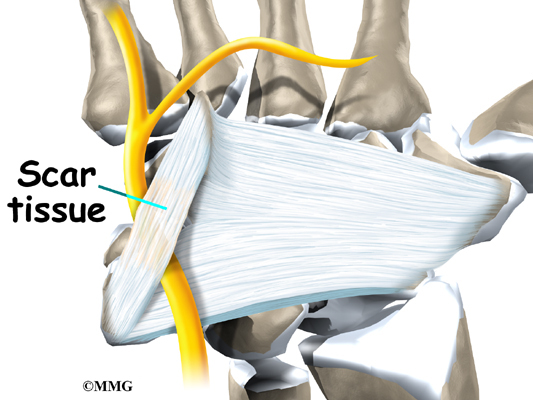

Once in view, the carpal ligament is released using a scalpel or scissors. Care is taken to make sure that the median nerve and flexor tendons are out of the way and protected. By cutting the carpal ligament, pressure is taken off the median nerve. Upon dividing the carpal ligament, the surgeon stitches just the skin together and leaves the loose ends of the carpal ligament separated. The loose ends are left apart to keep pressure off the median nerve. Eventually, the gap between the two ends of the ligament fills in with scar tissue. After the skin is stitched together, your hand will be wrapped in a bulky dressing. This surgery can usually be done as an outpatient procedure, meaning you can leave the hospital the same day.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following open carpal tunnel release are

- anesthesia

- infection

- incision pain

- scar tissue formation

- nerve damage

- hand weakness

Anesthesia

Problems can arise when the anesthesia given during surgery causes a reaction with other drugs the patient is taking. In rare cases, a patient may have problems with the anesthesia itself. In addition, anesthesia can affect lung function because the lungs don’t expand as well while a person is under anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Infection

Infection is a possible complication after surgery, especially infection of the incision. Therefore, check your incision every day as instructed by your surgeon. If you think you have a fever take your temperature. If you have signs of infection or other complications, call your surgeon right away.

These are warning signs of infection or other complications:

- pain in your hand that is not relieved by your medicine

- discharge with an unpleasant odor coming from your incision

- swelling, heat, and redness along your incision

- chills or fever over 100.4 degrees Fahrenheit

- bright red blood coming from your incision

Incision Pain

Some patients continue to have pain along their incision. The area often stays sensitive long after the surgery. However, symptoms of incision sensitivity tend to get better within four to six months after surgery.

Scar Tissue Formation

A common problem after carpal tunnel release is excessive scar tissue buildup. The body attempts to heal the area but goes too far in the process of supplying new cells. Too much scar tissue forms. When this happens the nearby soft tissues can become bound together. The incision may appear raised. The nearby skin may feel tight. You may even feel a bump beneath the incision. Wrist and hand movement may feel restricted. Scar tissue can also bind the flexor tendons and median nerve, preventing them from gliding smoothly within the carpal tunnel. Pain and a loss of range of motion may occur. In severe cases, a second surgery may be needed to remove the extra scar tissue.

Nerve Symptoms

Sometimes people still feel some numbness and tingling after surgery, especially if they had severe pressure on the median nerve prior to surgery. When the thenar muscles (mentioned earlier) are notably shrunken (atrophied) from prolonged pressure on the median nerve, full strength and normal sensation may not fully return even after having the surgery.

Hand Weakness

Muscles that are used to squeeze and grip may seem weak after surgery. During normal gripping, the tendons of the wrist press outward against the carpal ligament. This allows the carpal ligament to work like a pulley to improve grip strength. People used to think that the tendons lose this mechanical advantage after the carpal ligament has been released. However, recent studies indicate that hand weakness is more likely from pain or swelling that occurs in the early weeks after the procedure. With the exception of patients who have severe thenar atrophy at the time of surgery, most people achieve normal hand strength within two to four months of surgery. Those with severe atrophy commonly see improvements in hand strength, but they rarely regain normal size of the thenar muscles.

After Surgery

What happens immediately after surgery?

At first, take time during the day to support your healing arm with your hand elevated above the level of your heart. You may be instructed to put an ice pack on your wrist several times a day to keep swelling down. At various times during the day, move your thumb and fingers five to 10 times. Also, bend and straighten your elbow and lift and lower your shoulder occasionally to keep these joints limber. Keep the dressing on your hand until you return to the surgeon. Avoid getting the stitches wet. Your stitches will be removed 10 to 14 days after surgery.

Heavy gripping and pinching should be avoided for up to six weeks. These actions need to be avoided to keep the tendons from pushing out against the healing carpal ligament After six weeks, you should be safe to resume gripping and pinching without irritating the wrist.

It generally takes longer to recover after open carpal tunnel release. Pain and symptoms usually begin to improve, but you may have tenderness in the area of the incision for several months after surgery.

Patients who wait too long to seek medical advice sometimes have difficulty adjusting after surgery. Poor coping skills in the presence of persistent pain and numbness may result in disappointment or dissatisfaction with the results of surgery. Recovery may take longer than expected when nerve damage is severe. In some cases, symptoms are not entirely alleviated.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after surgery?

Many surgeons prefer to have their patients attend occupational or physical therapy sessions after the stitches are removed. Patients are treated two to three times each week for four to six weeks. As mentioned, however, it may take several months for the incision pain to go away and for maximum hand strength to return.

At first, therapists attempt to reduce pain and swelling. Common treatments include hot or cold packs, electrical stimulation, and ultrasound. Massage strokes directed from the fingers toward the elbow help move swelling away from the hand and wrist.

Therapists use hands-on stretching and active hand and wrist exercises to encourage range of motion. You’ll be shown how to carefully strengthen your hand by squeezing and stretching special putty. You’ll likely be given home exercises to improve hand and finger movement and strength.

Treatments are used to reduce sensitivity in the incision. The methods are applied gently at first. One method is for the therapist to massage the incision for several minutes. Patients learn the massage technique so they can do it on their own five to six times each day. Another way to desensitize the incision is to grip materials of various textures or to rub them over the incision. These treatments are gradually done with more vigor as the sensitivity of the incision eases.

Another therapy goal is to prevent scar tissue formation. Therapists use scar massage to reduce scar tissue formation in the incision and in the nearby skin and soft tissues. To prevent scar tissue from forming between the flexor tendons and median nerve, therapists instruct their patients in a series of fist positions. These specialized exercises encourage the normal gliding action of the structures within the carpal tunnel.

As you progress, your therapist will also give you exercises to help strengthen and stabilize the muscles and joints in the hand. Other exercises are used to improve fine motor control and dexterity. Some of the exercises you’ll do are designed to get your hand working in ways that are similar to your work tasks and sport activities.

Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don’t put too much stress on your hand and wrist. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

Mucous Cysts of the Fingers

A Patient’s Guide to Mucous Cysts of the Fingers

Introduction

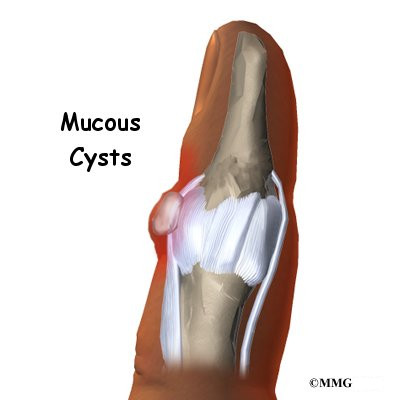

Mucous cysts are small, fluid-filled sacs that form on the fingers. They are associated with osteoarthritis (OA) and usually develop in patients 50 to 70 years old. These cysts appear between the last joint of the finger and the bottom of the fingernail. Unless a mucous cyst is painful or in danger of rupturing, it can be left alone without causing harm to the patient. But even surgically removing a mucous cyst may not alleviate pain if the underlying cause of the pain is OA.

This guide will help you understand

- what part of the finger is involved

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what can be done to treat a mucous cyst

Anatomy

What part of the finger is involved?

The bones of the fingers are called the phalanges. Each finger has three phalanges, separated by two interphalangeal joints (IP joints). The one closest to the knuckle is called the proximal IP joint (PIP joint). The joint near the end of the finger is called the distal IP joint (DIP joint).

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect bones. Several ligaments hold each finger joint together. These ligaments join to form the joint capsule of the finger joint. The joint capsule is a watertight sac around the joint. The joint surfaces are covered with a material called articular cartilage. This material is slick and spongy, and it allows one side of a joint to slide against the other joint surface easily. When this material wears out, the joint develops osteoarthritis (OA).

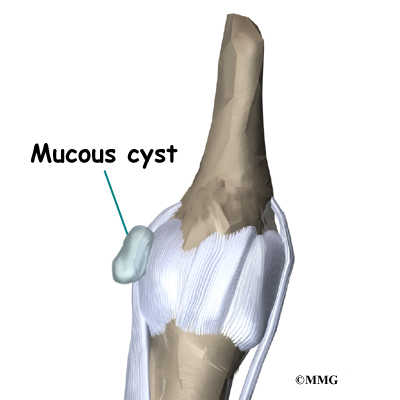

A mucous cyst is a type of ganglion, a small, harmless sac filled with a clear, sticky fluid. The fluid is a mix of chemicals normally found in the body. A mucous cyst is a ganglion of the DIP joint. The cyst is attached to the joint by a stalk of tissue. Typically only one cyst appears, though an occult (concealed) cyst may also be found closer to the joint.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

Why do I have this problem?

Mucous cysts are typically found in patients with OA. Doctors do not know why mucous cysts develop.

Doctors also don’t understand exactly how these cysts form. One theory suggests that mucous cysts are formed when connective tissue degenerates (wears away). Collagen is a protein found in connective tissue. The leftover collagen is thought to collect in pools, and the pools form cysts. Fluid seems to move from the joint into the cyst, but not the other way.

Symptoms

What does a mucous cyst feel like?

A mucous cyst is typically visible just under the skin on the finger. It may be painful. You may notice a groove in the fingernail just above the cyst. The groove is a result of pressure from the cyst on the nailbed. The skin over the cyst may have thinned.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the condition?

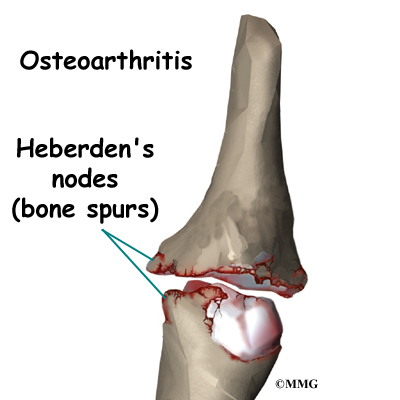

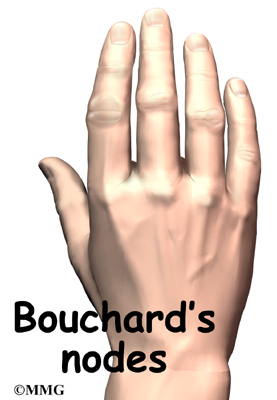

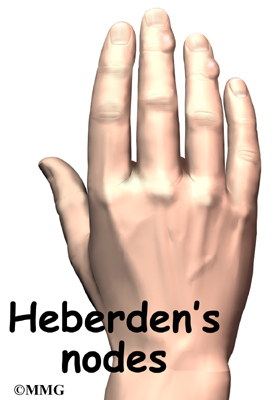

Your doctor will ask for a history of the problem and examine your fingers. Your doctor may also order an X-ray. An X-ray of the DIP joint may show degeneration related to OA, including bone spurs, joint space narrowing, and hardening of the subchondral bone, the layer of bone just below the articular cartilage in the joint. A patient may also have Heberden’s nodes. These are simply the bumps formed by bones spurs arising from the finger joint due to the OA.

Treatment

What can be done for the condition?

Treatment for mucous cysts may be either nonsurgical or surgical. The relative risks and benefits of any mucous cyst treatment should be considered carefully.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Observation is often sufficient treatment for mucous cysts. Mucous cysts are not typically harmful and usually do not grow worse without treatment.

However, sometimes a mucous cyst will rupture. When this occurs, it creates a path directly into the joint where bacteria could enter and cause a serious infection inside the joint. When this happens, antibiotics are applied directly to the site and the finger is wrapped in a dressing. Oral antibiotics are also prescribed. If the joint develops an infection despite these steps, surgery is required. During surgery, the area, including the DIP joint, is carefully cleaned, and a dressing is applied.

Surgery

Surgery is recommended if you feel significant pain or if the cyst and skin appear ready to rupture.

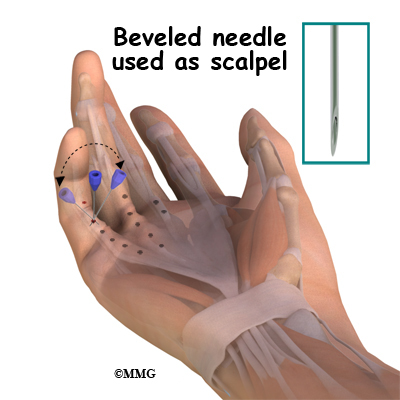

Needle puncture is one option. In this procedure, the cyst is punctured and aspirated. (Aspiration means drawing the fluid out with suction.) However, this procedure has less than a 50 percent success rate.

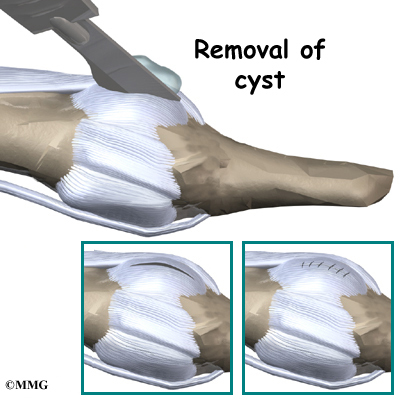

Another option involves excision (removal) of the cyst and its connection to the DIP joint. Patients should be aware that removing a mucous cyst may not eliminate pain if the pain is from the underlying OA.

In this procedure, the cyst, stalk, and any bone spurs on the DIP joint are removed. If the skin on the finger is too closely attached to the cyst, a bit of the skin may need to be removed from the finger. If that’s the case, a small skin graft is added to the spot. Surgery can usually be performed using regional anesthesia, meaning only the arm or finger is numbed with lidocaine.

Complications may occur with both procedures. A slight risk of infection exists with both. Even after an excision surgery, a mucous cyst may reappear, though this is rare.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect with treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Your doctor may simply have you observe for any changes in the cyst. During this period of observation, let your doctor know of any significant increases or decreases in the size of the cyst.

After Surgery

If you have surgery to remove a mucous cyst and a skin graft is used, you will wear a cast or splint for two weeks. Otherwise, the fingers can be moved sooner. You will be shown specific exercises to help you regain full motion in the finger. Exercises should be continued until you can move the finger normally without pain.

Thumb Arthritis

A Patient’s Guide to Arthritis of the Thumb

Introduction

When you stop to think about how much you use your thumbs, it’s easy to see why the joint where the thumb attaches to the hand can suffer from wear and tear. This joint is designed to give the thumb its rather large range of motion, but the tradeoff is that the joint suffers a lot of stress over the years. This can lead to painful osteoarthritis of this joint, thumb arthritis, that may require surgical treatment as the arthritis progresses.

This guide will help you understand

- how arthritis of the thumb develops

- how it is diagnosed

- what can be done for the condition

Anatomy

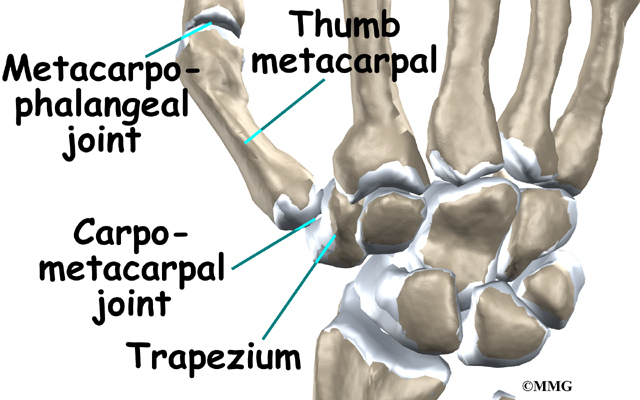

Where is the CMC joint, and what does it do?

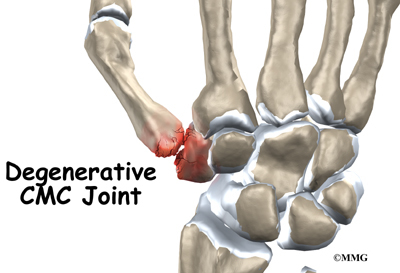

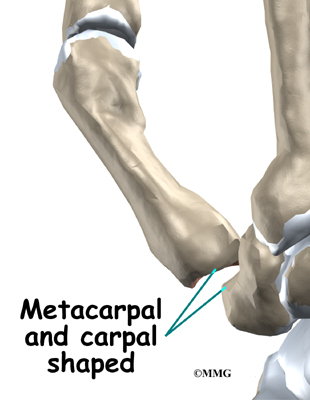

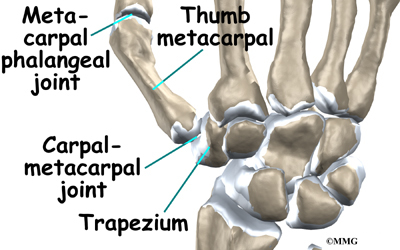

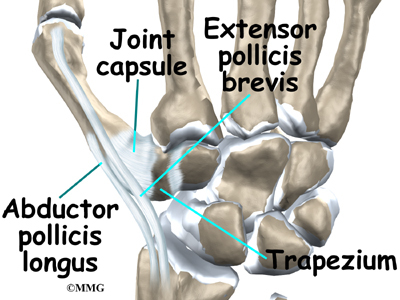

The CMC joint (an abbreviation for carpometacarpal joint) of the thumb is where the metacarpal bone of the thumb attaches to the trapezium bone of the wrist. This joint is sometimes referred to as the basal joint of the thumb. The CMC is the joint that allows you to move your thumb into your palm, a motion called opposition. The CMC joint is sometimes referred to as a universal joint because of the wide range of movements possible.

Several strong, thick ligaments hold the CMC joint together. The ligaments allow for motion but keep the joint from sliding too far and prevent thumb dislocation. This function is called ligamentous restraint. These ligaments can be injured, such as when you sprain your thumb. There are also nine muscles that provide dynamic stabilization of the CMC joint. These muscles coordinate together to create a balance of stability. They put the thumb in positions that allow optimal function for thumb-pinch activities.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

What causes arthritis of the thumb?

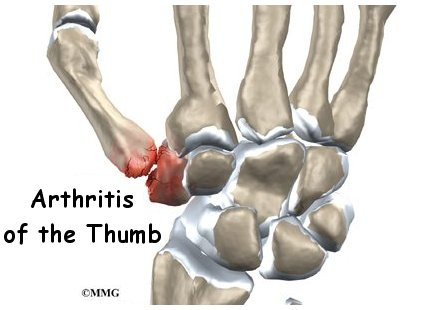

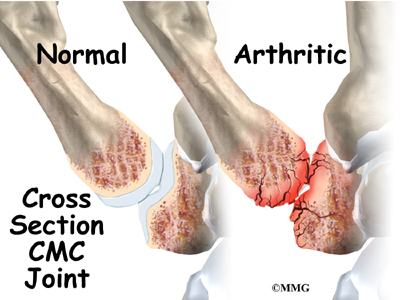

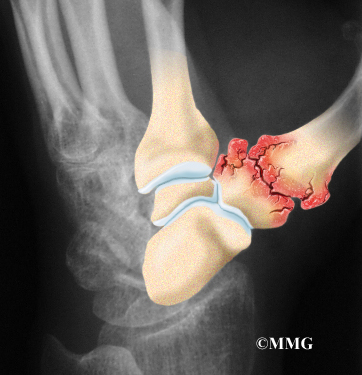

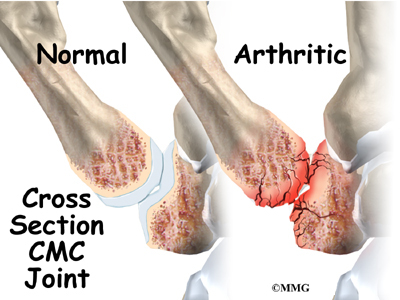

Arthritis is a condition in which a joint becomes inflamed (red, swollen, hot, and painful). Degenerative arthritis is a condition in which a joint wears out, usually slowly over a period of many years. Doctors sometimes also describe this same condition as degenerative arthrosis. It is also called osteoarthritis.

Injury to a joint, such as a bad sprain or fracture, can cause damage to the articular cartilage. An injury to the CMC joint of the thumb, even if it does not injure the articular cartilage directly, can alter how the joint works. After a fracture of the thumb metacarpal, the bone fragments may heal in slightly different positions. The joints may then line up differently. This is also true when the ligaments around the CMC joint are damaged by a sprain. When an injury results in a change in the way the joint moves, the injury may increase the forces on the articular cartilage surfaces. This is similar to any mechanical device or machinery. If the mechanism is out of balance, it tends to wear out faster.

Over many years this imbalance in the joint mechanics can lead to damage on the articular surface. Since articular cartilage cannot heal itself very well, the damage adds up. Eventually, the joint is no longer able to compensate for the increasing damage, and it begins to hurt. Damage has occurred well before the pain begins.

Women are three time more likely than men to develop arthritis of the CMC joint. There are several reasons for this. Women have higher amounts of certain hormones that are linked with joint laxity (looseness). There are also some anatomic differences in the joint surfaces between men and women. Increased joint motion from laxity combined with differences in the shape and surface of the bones add to the risk of CMC arthritis in women.

Adults with increased body mass index (BMI) are also at risk for CMC arthritis. There are two possible reasons for this relationship. First, increased mechanical loading seems to occur at the CMC joint in obese adults. This is true even though the thumb is not a weight-bearing joint. Over time, increased load translates into wear and tear on the joint.

Second, patients with a higher body mass index also have elevated levels of lipids (fats), hormones, and insulin-like growth factor around the joint. Local biochemical changes from these hormones may speed up joint degeneration.

Symptoms

What does arthritis of the thumb feel like?

Pain is the main problem with degenerative arthritis of any joint. This pain occurs at first only related to activity. Usually, once the activity gets underway there is not much pain, but after resting for several minutes the pain and stiffness increase. Later, when the condition worsens, pain and aching may be present even at rest. The most noticeable problem with CMC joint arthritis is that it becomes difficult to grip anything. It causes a sharp pain at the base of the thumb in the thick part of the heel of the hand.

When the articular cartilage starts to wear off the joint surface, the joint may make a squeaking sound when moved. Doctors refer to this sound as crepitus. The joint often becomes stiff and begins to lose motion. Moving the thumb away from the palm may become difficult. This is referred to as a contracture.

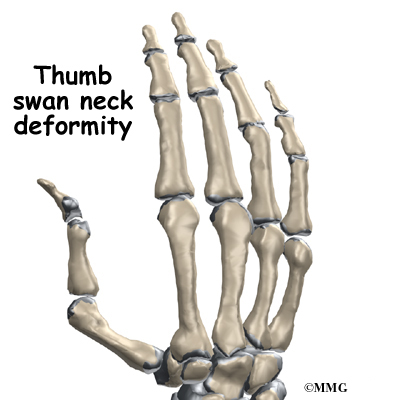

Osteoarthritis may cause the CMC joint of the thumb to loosen and to bend back too far (hyperextension). If the middle thumb joint (MCP joint) becomes flexed and the furthest thumb joint also becomes hyperextended, the deformity is named a thumb swan neck deformity. A similar finger deformity sometimes occurs in people with finger arthritis.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Swan Neck Deformity of the Finger

Diagnosis

How do doctors identify this problem?

The diagnosis of CMC joint arthritis of the thumb begins with your doctor taking a detailed history of the problem. Specifics about any injuries that may have occurred to the hand are important because they may suggest other reasons why the condition exists.

Following the history, the doctor will examine your hand and possibly other joints in your body. The doctor will need to see how the motion of the CMC joint has been affected.

X-rays will be taken to see how much the joint is damaged. This test usually determines how bad the degenerative arthritis has become. How much articular cartilage remains in the joint can be estimated with the X-rays.

Using X-ray findings, the condition is classified as stage I, II, III, or IV, depending on the condition of the joint cartilage and the joint space. In Stage I, there are no obvious changes on X-ray. By stage IV, bone spurs, narrowed joint space, and even joint dislocation may be seen. Although X-rays are important, radiographic staging of the disease does not predict the severity of symptoms or guide treatment.

Treatment

What can be done for CMC joint arthritis?

The treatment of degenerative arthritis of the CMC joint of the thumb is based on the severity of symptoms. The goals of treatment are to relieve pain, decrease disability, and prevent deformity. Treatment can be divided into the nonsurgical means to control the symptoms and the surgical procedures that are available to treat the condition. Surgery is usually not considered until the symptoms have become impossible to control without it.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment usually begins when the CMC joint first becomes painful. This may only occur with heavy use and may simply require mild anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Reducing the activity, or changing from occupations that require heavy repetitive gripping with the hand, may be necessary to help control the symptoms.

Rehabilitation services, such as physical and occupational therapy, have a critical role in the nonoperative treatment plan for CMC joint arthritis. A primary goal is to help you learn how to control symptoms and maximize the health of your thumb. You’ll learn ways to calm pain and symptoms, which might include the use of rest, heat, or topical rubs. Adaptive devices to assist with household chores, self-care, or even on-the-job tasks may be recommended.

A brace or splint may also be prescribed to support the thumb. These devices are designed to help reduce pain, prevent deformity, or keep a thumb deformity from getting worse. A thumb stabilizer is a type of thumb splint that is often custom-made of heat-moldable plastic. It is designed to fit the forearm, wrist, and thumb. Patients with CMC joint arthritis usually only wear the splint at night and when the joint is flared up. It should also be worn to protect the thumb during heavy or repeated hand and thumb activities.

Range-of-motion and stretching exercises are prescribed to improve your thumb motion. Strengthening exercises for the arm and hand help steady the hand and protect the thumb joint from shock and stress. Strengthening improves joint stability and prevents deformity and/or dislocation. Your therapist will go over tips on how you can get your tasks done with less strain on the joint.

An injection of cortisone into the joint can give temporary relief. Cortisone is a very powerful anti-inflammatory medication. When injected into the joint itself, it can help relieve the pain. Pain relief is temporary and usually only lasts several weeks to months. There is a small risk of infection with any injection into the joint, and cortisone injections are no exception.

Studies do not support the use of cortisone injections alone. Although temporary pain relief is possible, there is no long-term improvement in hand function, joint stiffness, or tenderness. Steroid injection(s) combined with splinting has been shown more successful in patients during the early stages of CMC arthritis.

Surgery

The surgical treatment for arthritis of the CMC joint includes several options. At one time, joint replacement with an artificial joint made with silicone was very popular. Problems with silicone implants in other parts of the body have led many surgeons to return to more traditional operations such as fusion and excision arthroplasty instead.

Newer artificial joints are being developed, and in the future we may see more surgeons using them. The best method to reduce pain and provide optimal function still remains uncertain. Research is underway to provide surgeons with evidence-based practice guidelines.

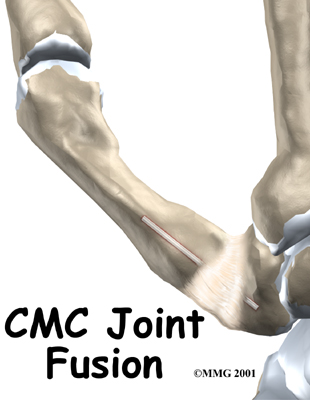

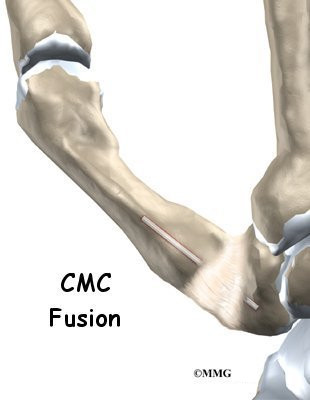

CMC Joint Fusion

A fusion, or arthrodesis, of any joint is designed to eliminate pain by allowing the bones that make up the joint to grow together, or fuse, into one solid bone. Fusions are used in many joints and were very common before the invention of artificial joints for the replacement of arthritic joints. Even today, joint fusions are still commonly used in many different joints for treating the pain of arthritis.

A fusion of the CMC joint of the thumb is done quite often in younger people who need a strong grip or pinch more than they need the fine motion of the thumb. People who use their hands for heavy work will probably prefer a fusion to an arthroplasty (described below).

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Thumb Fusion Surgery

Artificial Joint Replacement (Arthroplasty)

Artificial joints are available for the CMC joint. These plastic or metal prostheses are used by some hand surgeons to replace the joint. The prosthesis acts as a spacer to fill the gap created when the arthritic surfaces of the two bones that make up the CMC joint are removed.

Long-term results using silicone and Zirconia implants have not been widely successful. Early wear (after two years) has been reported as a result of the shear and compressive forces across the implant. In some cases, the implant sinks down into the bone causing increased pain and weakness. Titanium implants have reportedly excellent results but not all studies have had equally good outcomes. More research is needed to reduce complications and extend the life of the implant.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Thumb

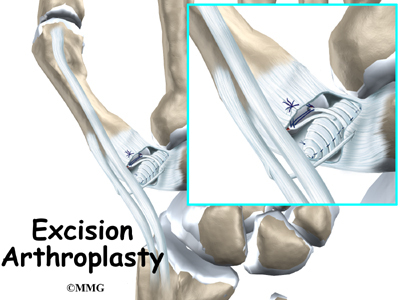

Resection (also called Excision) Arthroplasty

The traditional operation for treating CMC joint arthritis is resection (excision) arthroplasty. This method has been used for many years and has withstood the test of time. Patients with severe symptoms in stage III or IV CMC arthritis who have failed nonsurgical treatment are good candidates for resection arthroplasty.

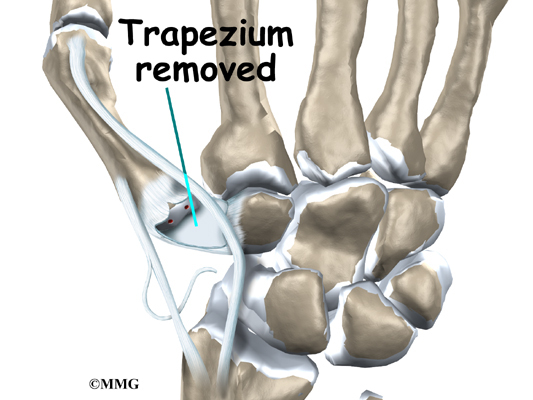

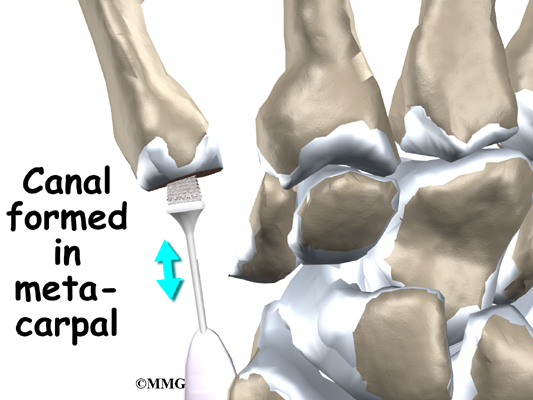

The purpose of resection arthroplasty is to remove the arthritic joint surfaces of the CMC joint and replace them with a cushion of material that will keep the bones separated. The trapezium bone is removed in a procedure called a trapeziectomy.

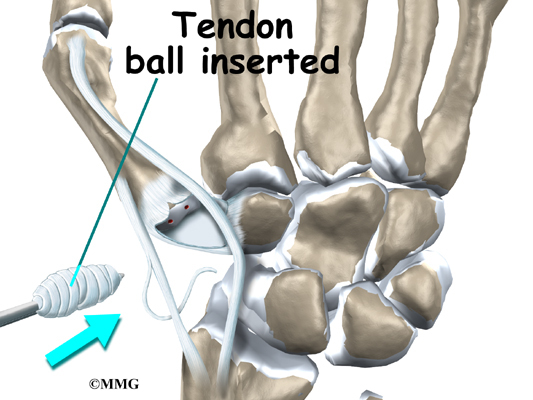

A rolled up piece of tendon is placed into the space created by removing the bone. This procedure is called a resection arthroplasty with ligament reconstruction and tendon interposition (LRTI). During the healing phase after surgery, this tendon turns into tough scar tissue that forms a flexible connection between the bones, similar to a joint. Sometimes the surgeon uses a silicone-based or metal implant or disc made of costochondral tissue instead of a rolled up tendon for the interpositional material. Costochondral allografts are plugs of tissue taken from the material between the breastbone and the ribs.

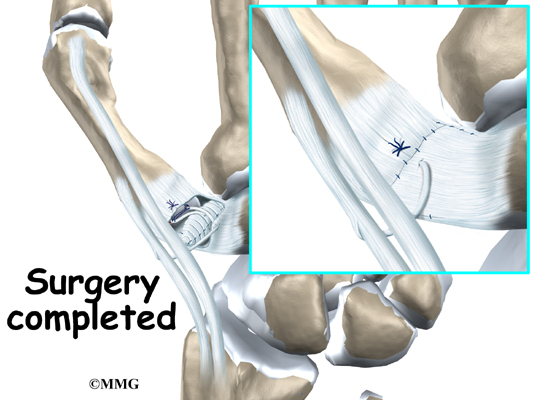

Resection arthroplasty with or without LRTI can be combined with a ligament reconstruction of the joint. Tendons in the area are used to create a ligament sling between the metacarpal bone of the thumb and the carpal bone of the index finger. This helps hold the thumb in place and keeps the space between the bones from collapsing.

Your surgeon decides whether to perform resection arthroplasty with or without tendon interposition and/or ligament reconstruction. Studies so far have not shown a biomechanical or clinical advantage to interposition. If there’s no evidence that this procedure improves pain, reduces stiffness, or increases pinch or grip strength, then it may fall out of favor. Surgeons will look for something more effective to achieve the intended treatment goals.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Resection (Excision) Arthroplasty of the Thumb

There can be complications with any surgical procedure. Infection, nerve injury, or continued pain can occur after surgery for CMC arthritis. When tendons are used as graft material for ligament reconstruction, problems can occur such as tendon rupture or tethering. Tethering means the tendon develops scarring or adhesions that bind it and keep it from gliding smoothly inside its sheath or outer covering.

With joint implants, there can be an inflammatory reaction, subsidence (the implant sinks down into the bone), dislocation, or other cystic changes.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect following treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

If you don’t need surgery, range-of-motion exercises for the thumb should be started as pain eases. Your therapist will work with you to obtain or create a special thumb splint (mentioned earlier) when needed. The program advances to include strength exercises for the thumb and fingers. Dexterity and fine motor exercises are used to get your hand and thumb moving smoothly. You’ll be given tips on keeping your symptoms controlled. You will probably progress to a home program within four to six weeks.

After Surgery

Your postoperative recovery and rehab program may depend on the type of surgery you had. For example, arthroscopy is much less invasive than open surgery and requires less time to recover. Your hand will be bandaged with a well-padded dressing and a thumb splint for support after arthroscopic, joint replacement, or ligament reconstructive surgery.

With fusion, there’s a high risk of nonunion so a cast is used to immobilize the joint for as much as three months. Often the thumb is fused in a functional position. The preferred position is a thumb key pinch. This means you can use the thumb to pinch and hold objects, but you won’t be able to open your hand flat. Getting your hand into a pocket will be more difficult, especially a pocket in tight pants.

Physical or occupational therapy sessions may be needed after surgery for up to eight weeks. The first few treatments are used to help control the pain and swelling after surgery. Some of the exercises you’ll begin to do are to help strengthen and stabilize the muscles around the thumb joint.

Other exercises are used to improve fine motor control and dexterity of your hand. You’ll be given tips on ways to do your activities while avoiding extra strain on the thumb joint.

Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

A Patient’s Guide to Carpal Tunnel Syndrome

Introduction

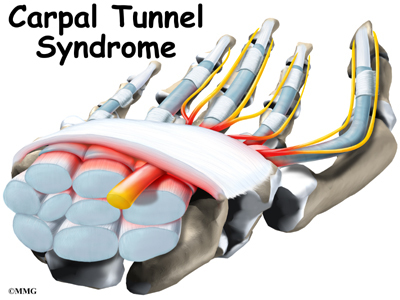

Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is a common problem affecting the hand and wrist. Symptoms begin when the median nerve gets squeezed inside the carpal tunnel of the wrist, a medical condition known as nerve entrapment or compressive neuropathy. Any condition that decreases the size of the carpal tunnel or enlarges the tissues inside the tunnel can produce the symptoms of CTS.

This syndrome has received a lot of attention in recent years because of suggestions that it may be linked with occupations that require repeated use of the hands, such as typing on a computer keyboard or doing assembly work. Actually, many people develop this condition regardless of the type of work they do.

This guide will help you understand

- where the carpal tunnel is located

- how CTS develops

- what can be done for the condition

Anatomy

Where is the carpal tunnel, and what does it do?

The carpal tunnel is an opening through the wrist to the hand that is formed by the bones of the wrist on one side and the transverse carpal ligament on the other. (Ligaments connect bones together.) This opening forms the carpal tunnel.

The median nerve passes through the carpal tunnel into the hand. It gives sensation to the thumb, index finger, long finger, and half of the ring finger. It also sends a nerve branch to control the thenar muscles of the thumb. The thenar muscles help move the thumb and let you touch the pad of the thumb to the tips of each finger on the same hand, a motion called opposition.

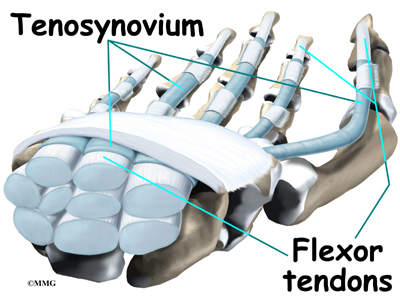

The median nerve and flexor tendons pass through the carpal tunnel. The median nerve rests on top of the tendons, just below the transverse carpal ligament. The flexor tendons are important because they allow movement of the fingers, thumb, and hand, such as when grasping. The tendons are covered by a material called tenosynovium. The tenosynovium is a slippery covering that allows the tendons to glide next to each other as they contract and relax to move the hand and fingers.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

What causes CTS?

Any condition that makes the area inside the carpal tunnel smaller or increases the size of the tissues within the tunnel can lead to symptoms of CTS. The carpal tunnel cannot expand so any condition that causes abnormal pressure in the tunnel can produce symptoms of CTS. And any increase in pressure within the carpal tunnel can reduce blood flow to the nerve, leading to loss of nerve function.

Various types of arthritis can cause swelling and pressure in the carpal tunnel. The way people do their tasks can put them at risk for problems of CTS. Some of these risks include

- force

- posture

- wrist alignment

- repetition

- temperature

- vibration

One of these risks alone may not cause a problem. But doing a task that involves several factors may pose a greater risk. And the longer a person is exposed to one or more risks, the greater the possibility of having a problem with CTS. However, scientists believe that other factors such as smoking, obesity, and caffeine intake may actually be more important in determining whether a person is more likely to develop CTS.

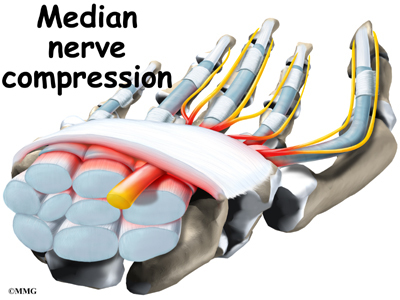

In other instances, CTS can start when the tenosynovium thickens from irritation or inflammation. This thickening causes pressure to build inside the carpal tunnel. But the tunnel can’t stretch any larger in response to the added swelling, so the median nerve starts to squeeze against the transverse carpal ligament. If the pressure continues to build up, the nerve is eventually unable to function normally.

When pressure builds on the median nerve, the blood supply to the outer covering of the nerve slows down and may even be cut off. The medical term for this is ischemia. At first, only the outside covering of the nerve is affected. But if the pressure keeps building up, the inside of the nerve will start to become thickened. New cells (called fibroblasts) form within the nerve and create scar tissue. This is thought to produce the feelings of pain and numbness in the hand. If pressure is taken off right away, the symptoms will go away quickly. Pressure that isn’t eased right away can slow or even stop the chances for recovery.

Trauma such as a wrist fracture, fracture/dislocation, infection, burns or other thermal injuries, bleeding disorders, and high-pressure injection injuries can result in a condition called i>acute carpal tunnel syndrome. This is much less common than the chronic compressive neuropathy caused by any of the risk factors described in this document.

A traumatic wrist injury may cause swelling and extra pressure within the carpal tunnel. The area inside the tunnel can also be reduced after a wrist fracture or dislocation if the bone pushes into the tunnel. Fractured wrist bones may later cause CTS if the healed fragments result in abnormal irritation on the flexor tendons.

Other conditions in the body can produce symptoms of CTS. Pregnancy can cause fluid to be retained, leading to extra pressure in the carpal tunnel. Diabetics may report symptoms of CTS, which may be from a problem in the nerve (called neuropathy) or from actual pressure on the median nerve. People with low thyroid function (called hypothyroidism) are more prone to problems of CTS. Tumors or cysts in the wrist, on the tendons, or in the carpal tunnel can also cause CTS.

Symptoms

What does CTS feel like?

One of the first symptoms of CTS is gradual tingling and numbness in the areas supplied by the median nerve. This is typically followed by dull, vague pain where the nerve gives sensation in the hand. The hand may begin to feel like it’s asleep, especially in the early morning hours after a night’s rest.

In the case of acute CTS, symptoms are sudden and severe, occurring over a matter of hours rather than weeks or months with the more chronic form of this condition.

Whether acute or chronic, pain associated with carpal tunnel syndrome may even spread up the arm to the shoulder. If the condition progresses, the thenar muscles of the thumb can weaken, causing the hand to be clumsy when picking up a glass or cup. If the pressure keeps building in the carpal tunnel, the thenar muscles may begin to atrophy (shrink).

Touching the pad of the thumb to the tips of the other fingers becomes difficult, making it hard to grasp items such as a steering wheel, newspaper, or telephone.

Diagnosis

How do doctors identify the condition?

Your doctor begins the evaluation by obtaining a history of the problem, followed by a thorough physical examination. Your description of the symptoms and the physical examination are the most important parts in the diagnosis of CTS. Commonly, patients will complain first of waking in the middle of the night with pain and a feeling that the whole hand is asleep.

Careful investigation usually shows that the little finger is unaffected. This can be a key piece of information to make the diagnosis. If you awaken with your hand asleep, pinch your little finger to see if it is numb also, and be sure to tell your doctor if it is or isn’t. Other complaints include numbness while using the hand for gripping activities, such as sweeping, hammering, or driving.

If your symptoms started after a traumatic wrist injury, X-rays may be needed to check for a fractured bone or a fracture with dislocation.

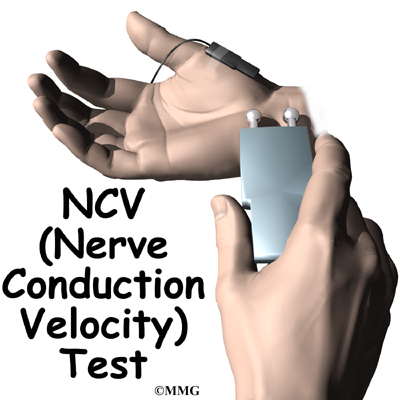

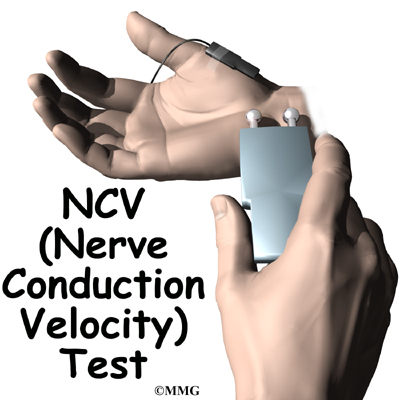

If more information is needed to make the diagnosis, electrical studies of the nerves in the wrist may be requested by your doctor. Several tests are available to see how well the median nerve is functioning, including the nerve conduction velocity (NCV) test. This test measures how fast nerve impulses move through the nerve.

Treatment

What can be done for CTS?

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons has published guidelines on the treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome. These guidelines reflect current research evidence and are included in this document. For the complete online version of the guidelines, see www.aaos.org/guidelines.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Activities that are causing your symptoms need to be changed or stopped if at all possible. Avoid repetitive hand motions, heavy grasping, holding onto vibrating tools, and positioning or working with your wrist bent down and out. If you smoke, talk to your doctor about ways to help you quit. Lose weight if you are overweight. Reduce your caffeine intake.

A wrist brace will sometimes decrease the symptoms in the early stages of CTS. A brace keeps the wrist in a resting position, not bent back or bent down too far. When the wrist is in this position, the carpal tunnel is as big as it can be, so the nerve has as much room as possible inside the carpal tunnel. A brace can be especially helpful for easing the numbness and pain felt at night because it can keep your hand from curling under as you sleep. The wrist brace can also be worn during the day to calm symptoms and rest the tissues in the carpal tunnel.

Anti-inflammatory medications may also help control the swelling and reduce symptoms of CTS. These include common over-the-counter medications such as ibuprofen and aspirin. Oral steroid medication may also offer some relief. In some studies, high doses of vitamin B-6 have been shown to help in decreasing CTS symptoms. Some types of exercises have also shown to help prevent or at least control the symptoms of CTS.

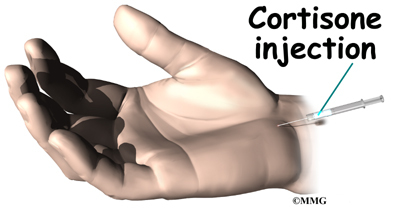

If these simple measures fail to control your symptoms, an injection of cortisone into the carpal tunnel may be suggested. This medication is used to reduce the swelling in the tunnel and may give temporary relief of symptoms.

A cortisone injection may help ease symptoms and can aid your doctor in making a diagnosis. If you don’t get even temporary relief from the injection, it could indicate that some other problem is causing your symptoms. When your symptoms do go away after the injection, it’s likely they are coming from a problem within the carpal tunnel. Some doctors feel this is a signal that a surgical release of the transverse carpal ligament would have a positive result.

Your doctor may suggest that you work with a physical or occupational therapist. The main focus of treatment is to reduce or eliminate the cause of pressure in the carpal tunnel. Your therapist may check your workstation and the way you do your work tasks. Suggestions may be given about the use of healthy body alignment and wrist positions, helpful exercises, and tips on how to prevent future problems. You might also receive treatments to reduce inflammation and to encourage normal gliding of the tendons and median nerve within the carpal tunnel.

Surgery

If all attempts to control your symptoms fail, surgery may be suggested to reduce the pressure on the median nerve. Surgery may not be advised if there is advanced nerve damage. Persistent pain and numbness may not go away with surgery. If you have muscle atrophy and weakness and/or loss of sensation, you may not be a good candidate for surgery.

And surgery may not be advised if electrodiagnostic studies show normal results. In such cases, patients seeking pain relief will be advised to continue with conservative (nonoperative) care.

In the case of acute CTS, surgery is required right away to decompress the nerve and save it from permanent damage. This is called nerve-sparing decompression. If a patient experiences a traumatic wrist or hand injury with worsening symptoms and increasing loss of hand function, carpal tunnel release is required.

When surgery is needed, several different surgical procedures have been designed to relieve pressure on the median nerve. By releasing the pressure on the nerve, the blood supply to the nerve improves, and most people get relief of their symptoms. However, if the nerve pressure has been going on a long time, the median nerve may have thickened and scarred to the point that recovery after surgery is much slower.

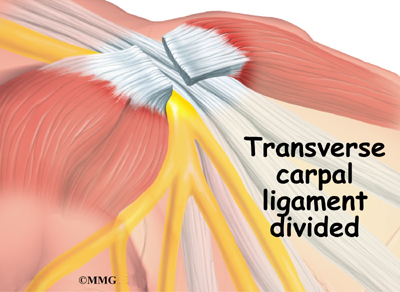

Open Release

The standard surgery for CTS is called open release. Open surgical procedures use a small skin incision. In open release for CTS, an incision as small as one inch can be made down the front of the wrist and palm. By creating an open incision, the surgeon is able to see the wrist structures and to carefully do the operation. The surgeon cuts the transverse carpal ligament in order to take pressure off the median nerve.

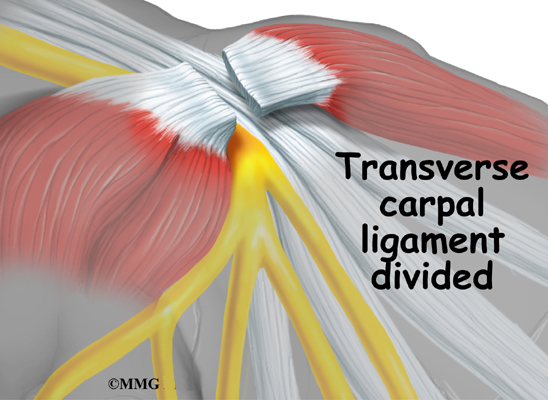

After dividing the transverse carpal ligament, the surgeon stitches just the skin together and leaves the loose ends of the transverse carpal ligament separated. The loose ends are left apart to keep pressure off the median nerve. Eventually, the gap between the two ends of the ligament fills in with scar tissue.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Open Carpal Tunnel Release

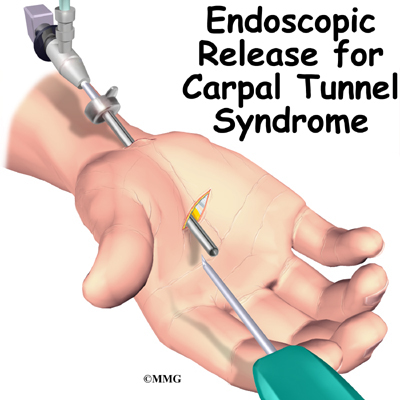

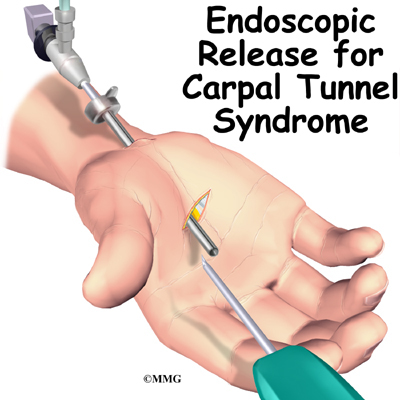

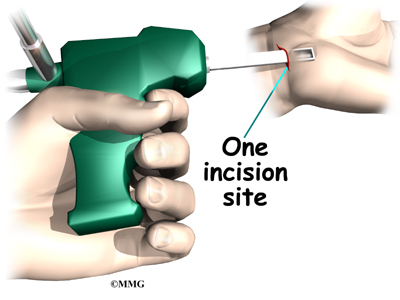

Endoscopic Release

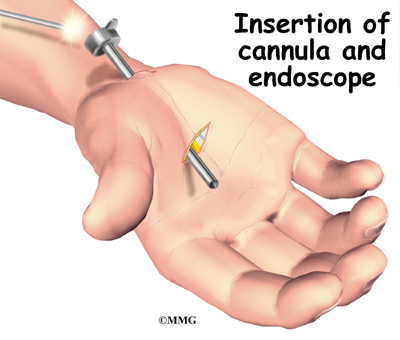

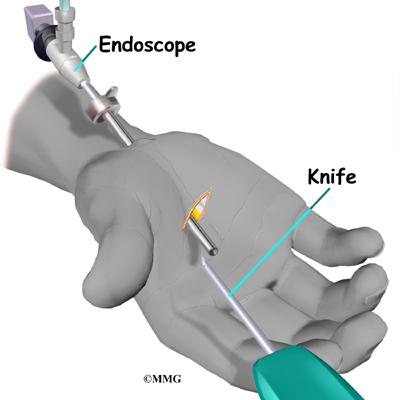

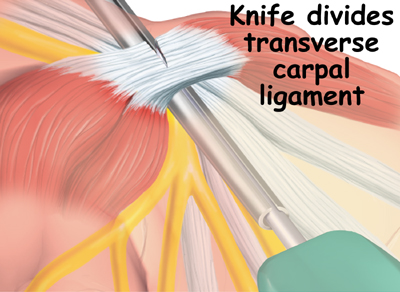

Some surgeons are using a newer procedure called endoscopic carpal tunnel release. The surgeon merely nicks the skin in order to make one or two small openings for inserting the endoscope. An endoscope is a thin, fiber-optic TV camera that allows the surgeon to see inside the carpal tunnel as the transverse carpal ligament is carefully released.

Upon inserting the endoscope, the surgeon can see the wrist structures on a TV screen. A special knife is used to cut only the transverse carpal ligament. The palmar fascia and the skin over the wrist are not disturbed.

As in open release, the loose ends of the transverse carpal ligament are left apart after endoscopic release to keep pressure off the median nerve. The gap eventually fills in with scar tissue.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Endoscopic Carpal Tunnel Release

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

If nonsurgical treatment is successful, you may see improvement in four to six weeks. You may need to continue wearing your wrist splint at night to control symptoms and keep your wrist from curling under as you sleep. Try to do your activities using healthy body and wrist alignment. Limit activities that require repeated motions, heavy grasping, and vibration in the hand.

After Surgery

It generally takes longer to recover after open carpal tunnel release. Pain and symptoms usually begin to improve, but you may have tenderness in the area of the incision for several months after surgery.

Patients who wait too long to seek medical advice sometimes have difficulty adjusting after surgery. Poor coping skills in the presence of persistent pain and numbness may result in disappointment or dissatisfaction with the results of surgery. Recovery may take longer than expected when nerve damage is severe. In some cases, symptoms are not entirely alleviated.

When the stitches are removed, your surgeon may have you work with a physical or occupational therapist for six to eight weeks. Treatments are used at first to ease pain and inflammation. Gentle massage to the incision can help reduce sensitivity in and around the incision and limit scar tissue from building up. Special exercises are used to encourage normal gliding of the tendons and median nerve within the carpal tunnel.

As you progress, your therapist will give you exercises to help strengthen and stabilize the muscles and joints in the hand, wrist, and arm. Other exercises are used to improve fine motor control and dexterity of the hand. Your therapist will work with you to help you do your daily and work activities safely and with the least amount of strain on your wrist and hand.

Mallet Finger Injuries

A Patient’s Guide to Mallet Finger Injuries

Introduction

When you think about how much we use our hands, it’s not hard to understand why injuries to the fingers are common. Most of these injuries heal without significant problems, however some do not. One such injury is an injury to the distal interphalangeal, or DIP, joint of the finger. This joint is commonly injured during sporting activities such as baseball. If the tip of the finger is struck with the ball, the tendon that attaches to the small bone underneath can be injured. Untreated, this can cause the end of the finger to fail to straighten completely, a condition called mallet finger.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the DIP finger joint

- what types of injuries affect this joint

- how the injury is treated

- what to expect from treatment

Anatomy

What parts of the finger are involved?

The finger joints work like hinges when the fingers bend and straighten. The main knuckle joint is the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP joint). It is formed by the connection of the metacarpal bone in the palm of the hand with the first finger bone, or proximal phalanx. Each finger has three phalanges, or small bones, separated by two interphalangeal joints (IP joints). The one closest to the MCP joint (knuckle) is called the proximal IP joint (PIP joint). The joint near the end of the finger is called the distal IP joint (DIP joint).

The extensor tendon is attached to the base of the distal phalanx. When it tightens, the DIP joint straightens. Another tendon, the flexor tendon, is attached to the palm of the finger. When it pulls, the DIP joint bends.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

How do these injuries of the DIP joint occur?

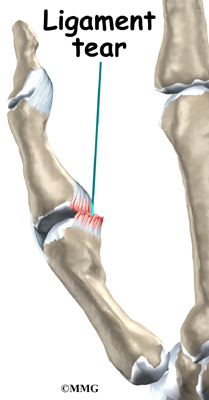

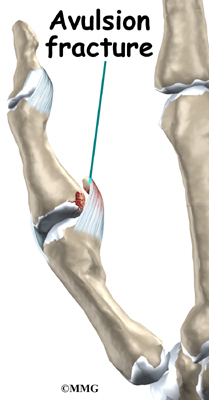

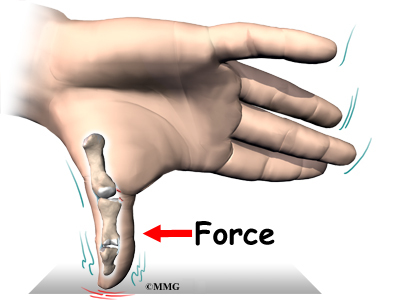

A mallet finger results when the extensor tendon is cut or torn from the attachment on the bone. Sometimes, a small fragment of bone may be pulled, or avulsed, from the distal phalanx. The result is the same in both cases: the end of the finger droops down and cannot be straightened.

Symptoms

What do mallet finger injuries look and feel like?

Initially, the finger is painful and swollen around the DIP joint. The end of the finger is bent and cannot be straightened voluntarily. The DIP joint can be straightened easily with help from the other hand. If the DIP joint gets stuck in a bent position and the PIP joint (middle knuckle) extends, the finger may develop a deformity that is shaped like a swan’s neck. This is called a swan neck deformity.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Swan Neck Deformity of the Finger

Diagnosis

What tests will my doctor do?

Usually the diagnosis is evident from the physical examination. X-rays are required to see if there is an associated avulsion fracture since this may change the recommended treatment. No other tests are normally required.

Treatment

What can be done for the problem?

Nonsurgical Treatment

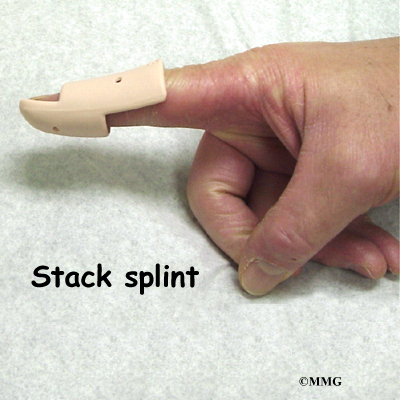

Treatment for mallet finger is usually nonsurgical. If there is no fracture, then the assumption is that the end of the tendon has been ruptured, allowing the end of the finger to droop. Usually continuous splinting for six weeks followed by six weeks of nighttime splinting will result in satisfactory healing and allow the finger to extend.

The key is continuous splinting for the first six weeks. The splint holds the DIP joint in full extension and allows the ends of the tendon to move as close together as possible. As healing occurs, scar formation repairs the tendon. If the splint is removed and the finger is allowed to bend, the process is disrupted and must start all over again. The splint must remain on at all times, even in the shower.

While a simple homemade splint will work, there are many splints that have been designed to make it easier to wear at all times. In some extreme cases where the patient has to use the hands to continue working (such as a surgeon), a metal pin can be placed inside the bone across the DIP joint to act as an internal splint and allow the patient to continue to use the hand. The pin is removed at six weeks.

Splinting may even work when the injury is quite old. Most doctors will splint the finger for eight to 12 weeks to see if the drooping lessens to a tolerable amount before considering surgery.

Surgery

DIP Fixation

Surgical treatment is reserved for unique cases. The first is when the result of nonsurgical treatment is intolerable. If the finger droops too much, the tip of the finger gets caught as you try to put your hand in a pocket. This can be quite a nuisance. If this occurs, the tendon can be repaired surgically, or the joint can be fixed in place. A surgical pin acts like an internal cast to keep the DIP joint from moving so the tendon can heal. The pin is removed after six to eight weeks.

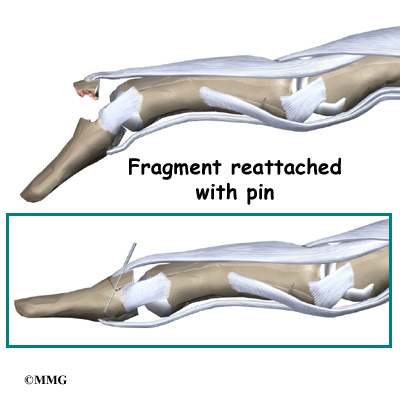

Fracture Pinning

The other case is when there is a fracture associated with the mallet finger. If the fracture involves enough of the joint, it may need to be repaired. This may require pinning the fracture. If the damage is too severe, it may require fusing the joint in a fixed position.

Finger Joint Fusion

If the damage cannot be repaired using pin fixation, finger joint fusion may be needed. Joint fusion is a procedure that binds the two joint surfaces of the finger together, keeping them from rubbing on one another. Fusing the two joint surfaces together eases pain, makes the joint stable, and prevents additional joint deformity.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Finger Fusion Surgery

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

When the injury is new, the DIP joint is splinted nonstop in full extension for six to eight weeks. A mallet finger that is up to three months old may require splinting in full extension for eight to 12 weeks. The splint is then worn for shorter periods that include nighttime splinting for six more weeks. Skin problems are common with prolonged splinting. Patients should monitor the skin under their splint to avoid skin breakdown. If problems arise, a new or different splint may be needed. Nearby joints may be stiff after keeping the finger splinted for this length of time. Therapy and exercise may be needed to assist in finger range of motion and to reduce joint stiffness.

After Surgery

Rehabilitation after surgery for mallet finger focuses mainly on keeping the other joints mobile and preventing stiffness from disuse. A physical or occupational therapist may be consulted to teach you home exercises and to make sure the other joints do not become stiff. After the surgical pin has been removed, exercises may be instituted gradually to strengthen the finger and increase flexibility.

PIP Joint Injuries of the Finger

A Patient’s Guide to PIP Joint Injuries of the Finger

Introduction

We use our hands constantly, placing them in harm’s way continuously. Injuries to the finger joints are common and usually heal without significant problems. Some injuries are more serious and may develop problems if not treated carefully. One such injury is a sprain of the proximal interphalangeal joint, or PIP joint, of the finger. This joint is one of the most unforgiving joints in the body to injury. What appears at first to be a simple sprain of the PIP joint may result in a painful and stiff finger, making it difficult to use the hand for gripping activities.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the PIP finger joint

- what types of injuries affect this joint

- how the injury is treated

- what to expect from treatment

Anatomy

What parts of the finger are involved?

The finger joints work like hinges when the fingers bend and straighten. The main knuckle joint is the metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP joint). It is formed by the connection of the metacarpal bone in the palm of the hand with the finger bone, or phalange. Each finger has three phalanges, separated by two interphalangeal joints (IP joints). The one closest to the MCP joint (knuckle) is called the proximal IP joint (PIP joint). The joint near the end of the finger is called the distal IP joint (DIP joint).

Ligaments are tough bands of tissue that connect bones together. Several ligaments hold the joints together. In the PIP joint, the strongest ligament is the volar plate. This ligament connects the proximal phalanx to the middle phalanx on the palm side of the joint. The ligament tightens as the joint is straightened and keeps the joint from hyperextending. There is also a collateral ligament on each side of the PIP joint. The collateral ligaments tighten when the joint is bent sideways and keep the joint stable from side to side.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hand Anatomy

Causes

How do these injuries of the PIP joint occur?