A Patient’s Guide to Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Introduction

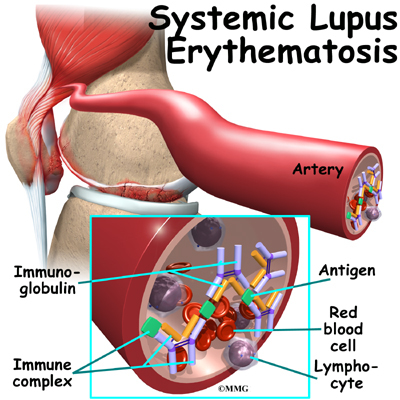

Systemic lupus erythematosus (also called SLE, or lupus) is an autoimmune disease of the body’s connective tissues. Autoimmune means that the immune system attacks the tissues of the body. In SLE, the immune system primarily attacks parts of the cell nucleus.

SLE affects tissues throughout your body. Five times as many women as men get SLE. Most people develop the disease between the ages of 15 and 40, although it can show up at any age.

This guide will help you understand

- how SLE develops

- how doctors diagnose the disease

- what can be done for the condition

Anatomy

Where does SLE develop?

SLE causes tissue inflammation and blood vessel problems pretty much anywhere in the body. SLE particularly affects the kidneys. The tissues of the kidneys, including the blood vessels and the surrounding membrane, become inflamed (swollen), and deposits of chemicals produced by the body form in the kidneys. These changes make it impossible for the kidneys to function normally.

The inflammation of SLE can be seen in the lining, covering, and muscles of the heart. The heart can be affected even if you are not feeling any heart symptoms. The most common problem is bumps and swelling of the endocardium, which is the lining membrane of the heart chambers and valves.

SLE also causes inflammation and breakdown in the skin. Rashes can appear anywhere, but the most common spot is across the cheeks and nose.

Causes

Why do I have this problem?

Doctors and researchers know quite a bit about the changes in the bodies of SLE patients. But the cause of SLE is a mystery.

Heredity plays a role in SLE. If you have a close relative who suffers from SLE, you are much more likely to develop the disease yourself. However, genes alone do not seem to cause SLE. It seems to be triggered in unknown ways. Not everyone with a tendency toward SLE will develop the disease. Researchers think some of the triggers that set off SLE may be infections, stress, diet, and toxins, including some kinds of prescription drugs. These triggers may also help explain why SLE has a cycle of flare-ups and remissions.

Symptoms

What does SLE feel like?

The symptoms of SLE come on in waves, called flares or flare-ups. In between flares, patients may have almost no symptoms. Almost every SLE patient suffers from general discomfort, extreme fatigue, fever, and weight loss at some point. In addition to these general symptoms, SLE produces different symptoms in different body systems.

Skin

Rashes caused by SLE are red, itchy, and painful. The rash can show up on any part of the body. The most typical SLE rash is called the butterfly rash, which appears on the cheeks and across the nose. SLE also causes hair loss. The hair usually grows back once the disease is under control.

People with SLE tend to be very sensitive to sunlight. Being in the sun for even a short time can cause a painful rash. Some people even get a rash from fluorescent lights at work.

Muscles and Bones

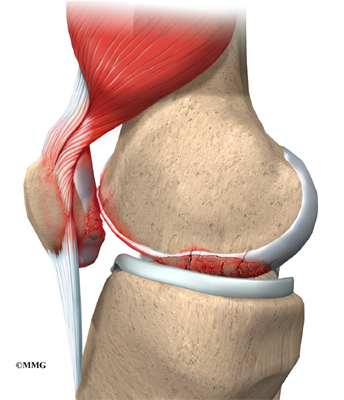

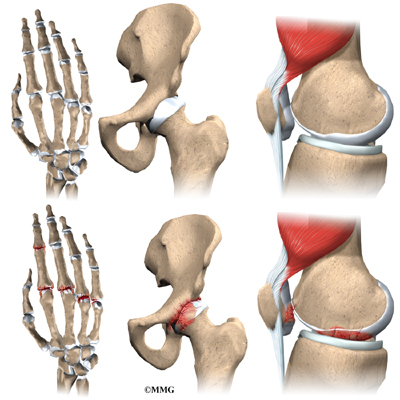

Almost everyone with SLE has joint pain or inflammation. Any joint can be affected, but the most common spots are the hands, wrists, and knees. Usually the same joints on both sides of the body are affected. The pain can come and go, or it can be long lasting. The soft tissues around the joints are often swollen, but there is usually no excess fluid in the joint. Many SLE patients describe muscle pain and weakness, and the muscle tissue can swell.

In its late stages, SLE can cause areas of bone tissue to die, called osteonecrosis.. Osteonecrosis can cause serious disability. It can be caused at least in part by using high doses of corticosteroids over a long time. Corticosteroids help control the symptoms of SLE.

Kidneys

People with SLE usually don’t notice any problems with their kidneys until the damage is severe. Sometimes kidney problems aren’t noticed until the kidneys are actually failing.

Nervous System

SLE can cause headaches, seizures, abnormal blood vessels in the head, and many other problems with the nervous system. SLE can also cause organic brain syndrome. This disorder involves serious problems with memory and concentration, emotional problems, and severe agitation and hallucinations. Any of these symptoms may show up alone, without any other symptoms of SLE.

Membranes

In the body, membranes surround your internal organs. The membranes around your lungs, heart, and the organs in the abdomen become inflamed in SLE. This is called serositis and can be seen on X-rays. Many SLE patients develop symptoms of pleurisy (swelling of the membrane around your lungs). The pericardium, the membrane around your heart, is often affected as well.

Digestive System

Problems with the stomach and intestines are common. Symptoms include abdominal pain, loss of appetite, nausea, and sometimes vomiting. In most cases this is caused by serositis in the membrane around the organs in your abdomen.

Lungs

SLE can cause many lung problems.

- Inflammation of the lungs, called Lupus pneumonitis, can come on suddenly or slowly. It has many of the same symptoms of pneumonia.

- A hemorrhage (burst blood vessel) can occur in the lungs.

- A blood clot can form in the artery going to the lungs.

- The blood vessels in the lungs can begin to contract.

- Shrinking lung syndrome involves scarring of the lungs due to long standing inflammation decreases the lungs’ capacity to take in air. It seems that the lungs can no longer hold normal amounts of air.

Blood

SLE causes very low levels of red and white cells in your blood. SLE often does not directly cause low levels of red blood cells, called anemia. Anemia is instead caused by blood loss, kidney problems, or the drugs taken to control the disease.

You may have few of these symptoms, almost all of them, or any combination in between. The disease affects different people in very different ways. There is even a group of patients considered to have latent lupus. They have some chronic SLE symptoms, but the disease never seems to progress into true SLE.

A few patients have drug-induced lupus. In these cases, SLE symptoms come on suddenly while taking certain kinds of drugs. The symptoms are usually milder than in true SLE, and the symptoms go away when the patients stop taking the drug.

Pregnancy

Because so many SLE patients are young women, pregnancy is a major concern. Women with SLE can get pregnant. The disease can be managed during pregnancy if it has already been brought under control. However, the chances of miscarriage, premature birth, and death of the baby in the uterus are high.

Diagnosis

How do doctors identify the condition?

Your description of symptoms and a detailed medical history will help your doctor make a diagnosis. Your doctor will also do a complete physical exam. You will be asked to give a blood sample.

The exams and tests your doctor will do to diagnose SLE depend on your symptoms. You may be asked to have X-rays taken of joints or organs. You may need to have an ultrasound of your heart or kidneys. Many other tests and exams can help diagnose SLE. Because SLE can develop and change over time, your doctor may ask you to do some of these tests again, to help monitor your disease.

Treatment Options

What can be done for SLE?

Treatment options for SLE have improved dramatically since the 1970s. SLE cannot be “cured” and will most likely be a lifelong disease that will require management and attention. You and your doctor should be able to find ways to manage flare-ups.

Lifestyle Alterations

One of the most important parts of dealing with SLE is learning about your own disease. The more you know, the better you can help yourself. Many patients find support groups helpful, both to learn about the disease and to meet others with SLE.

The skin of many SLE patients is extremely sensitive to sunlight. To avoid painful rashes, avoid going outside during the middle of the day, use sunscreen, and wear hats and long clothing.

Infections are common with SLE. If you come down with a fever, talk to your doctor right away. This is especially important if you are on certain drugs, including high-dose corticosteroids and cytotoxic drugs, those that are destructive to cells.

Birth control is important in women with SLE. It is especially important in women with kidney disease. Many of the drugs used to treat SLE can harm a growing fetus, so any pregnancy must be planned with the help of your doctor.

Medication

Several types of drugs can be used to treat the complications of SLE. What your doctor prescribes for you will depend on your symptoms.

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are used to treat muscle, bone, and joint pain, and mild cases of serositis (inflammation of internal membranes). They may also be used for fevers.

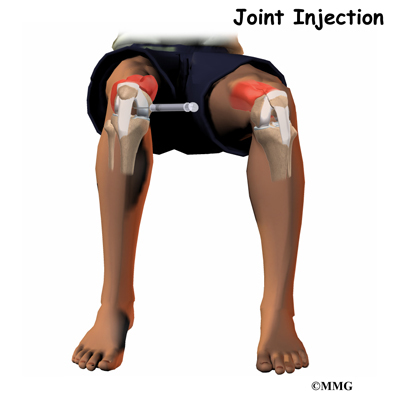

- Corticosteroids are used in many forms. Creams are rubbed into rashes, and oral or intravenous forms are used to treat flare-ups and to keep the disease under control. Corticosteroids can be injected directly into painful arthritic joints. These drugs are very toxic, however. It is important to use them only when absolutely necessary.

- Antimalarial drugs (hydroxychloroquine, chloroquine, and quinacrine) work to manage the skin problems of SLE. They can also help treat other symptoms. These drugs can hurt your eyes. As a precaution, you may need to get regular eye exams if you take antimalarial drugs.

- Methotrexate in low weekly doses can help manage arthritis, rashes, serositis, and other symptoms.

- Cyclophosphamide, given intravenously, is often used when SLE is affecting the kidneys, heart, and lungs. This is an extremely toxic drug, with many side effects. Patients often experience severe nausea and vomiting and almost total hair loss. The hair does grow back, even when patients must continue taking the drug.

- Azathioprine can be used instead of cyclophosphamide to treat kidney disease. Doctors consider it less effective, but it is also far less toxic. It can also be used instead of steroids.

SLE progressively damages the kidneys over time. In late stages of the disease, kidney failure requires dialysis or kidney transplants.

SLE is a very serious disease. Its effects on the kidneys, heart, and lungs can cause many long-term problems. Although doctors now have better ways to help you live with SLE, there are not many options to help prevent or reverse the damage to your organs.