Elbow

Elbow Dislocation

A Patient’s Guide to Elbow Dislocation

Introduction

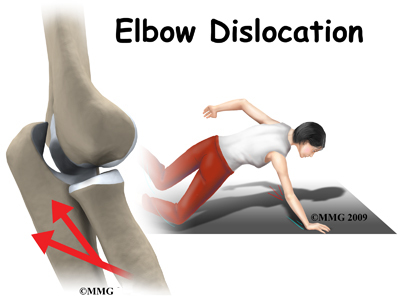

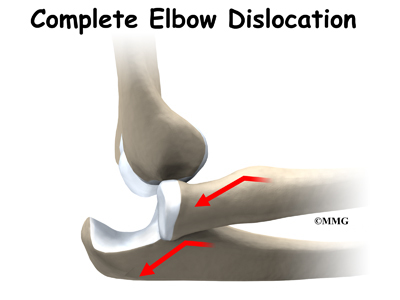

When the joint surfaces of an elbow are forced apart, the elbow is dislocated. The elbow is the second most commonly dislocated joint in adults (after shoulder dislocation). Elbow dislocation can be complete or partial. A partial dislocation is referred to as a subluxation. The amount of force needed to cause an elbow dislocation is enough to cause a bone fracture at the same time. These two injuries (dislocation-fracture) often occur together.

This guide will help you understand

- how the condition develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

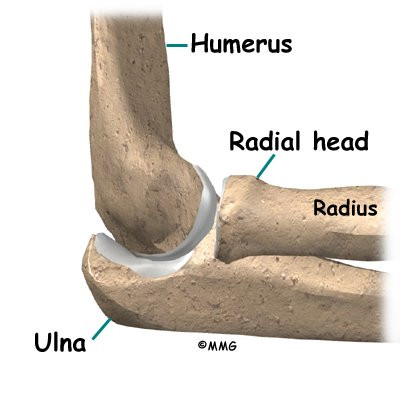

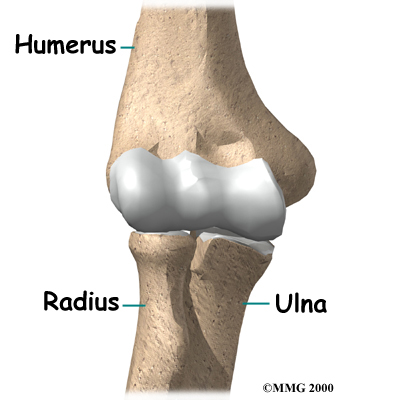

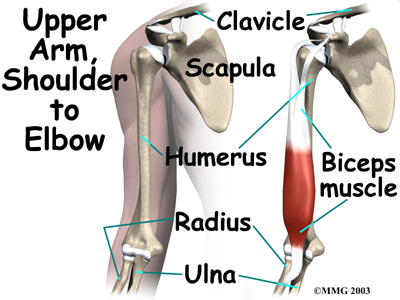

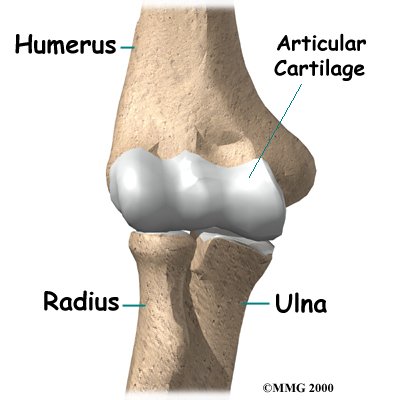

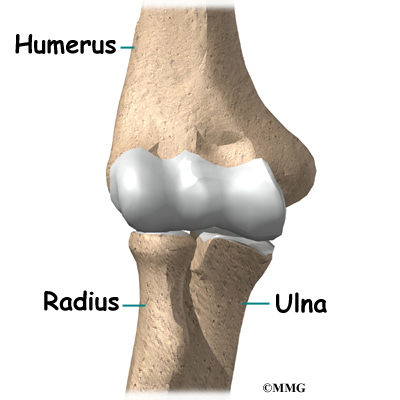

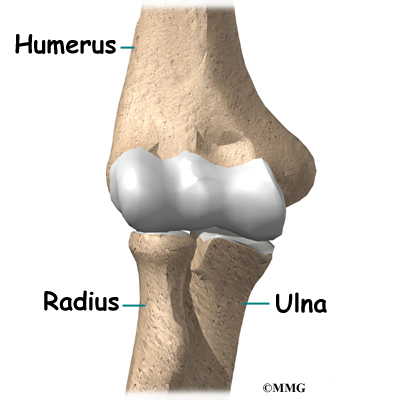

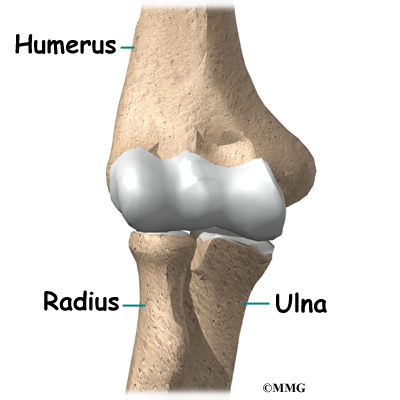

The bones of the elbow are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the ulna (the larger bone of the forearm, on the opposite side of the thumb), and the radius (the smaller bone of the forearm on the same side as the thumb).

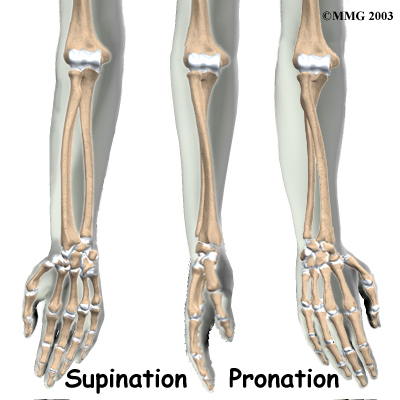

The elbow itself is essentially a hinge joint, meaning it bends and straightens like a hinge. But there is a second joint where the end of the radius (the radial head) meets the humerus. This joint is complicated because the radius has to rotate so that you can turn your hand palm up and palm down. At the same time, it has to slide against the end of the humerus as the elbow bends and straightens. The joint is even more complex because the radius has to slide against the ulna as it rotates the wrist as well. As a result, the end of the radius at the elbow is shaped like a smooth knob with a cup at the end to fit on the end of the humerus. The edges are also smooth where it glides against the ulna.

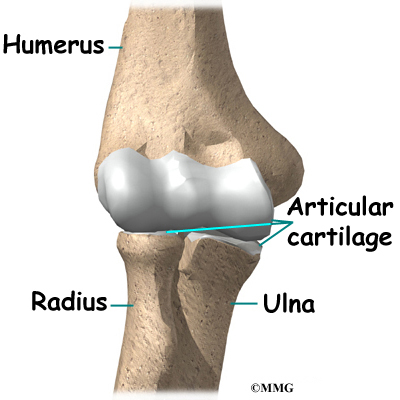

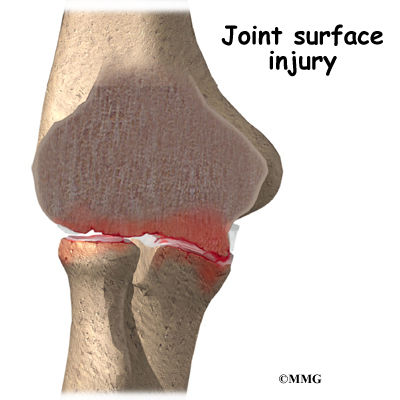

Articular cartilage is the material that covers the ends of the bones of any joint. Articular cartilage can be up to one-quarter of an inch thick in the large, weight-bearing joints. It is a bit thinner in joints such as the elbow, which don’t support weight. Articular cartilage is white, shiny, and has a rubbery consistency. It is slippery, which allows the joint surfaces to slide against one another without causing any damage. In the elbow, articular cartilage covers the end of the humerus, the end of the radius, and the end of the ulna.

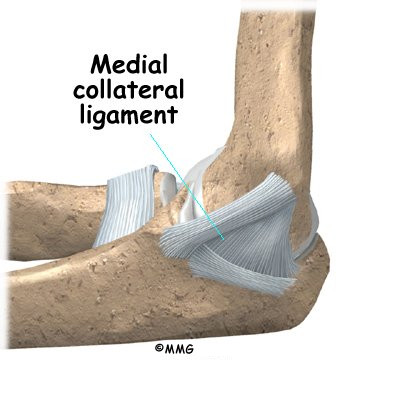

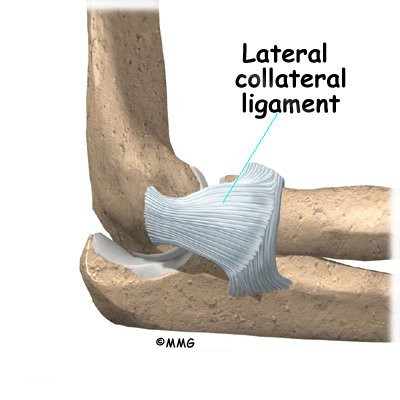

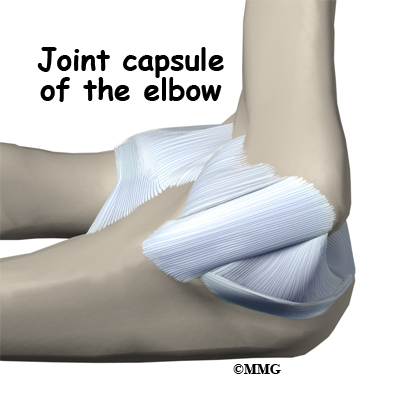

There are several important ligaments in the elbow. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. The ligaments around a joint usually combine together to form a joint capsule. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint and contains lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

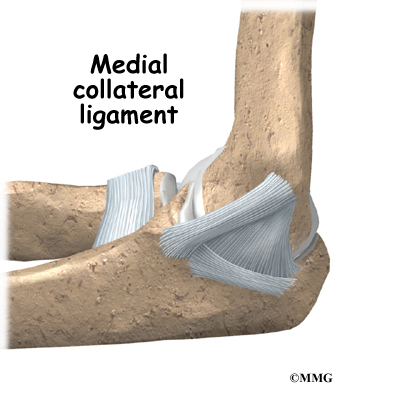

In the elbow, two of the most important ligaments are the medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament. The medial collateral is on the inside edge of the elbow, and the lateral collateral is on the outside edge. Together these two ligaments connect the humerus to the ulna and keep it tightly in place as it slides through the groove at the end of the humerus. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the elbow. They can be torn when there is an injury to or dislocation of the elbow. If they do not heal correctly the elbow can be too loose, or unstable.

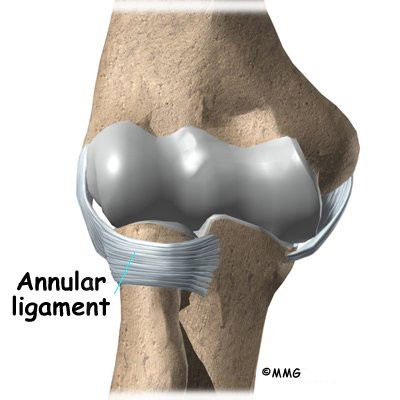

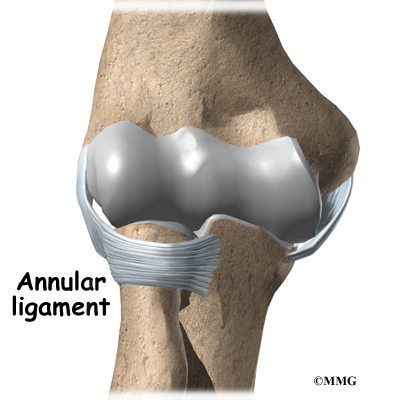

There is also an important ligament called the annular ligament that wraps around the radial head and holds it tight against the ulna. The word annular means ring-shaped. The annular ligament forms a ring around the radial head as it holds it in place. This ligament can be torn when the entire elbow or just the radial head is dislocated.

Causes

What causes this condition?

Elbow dislocation is often the result of trauma. The most common trauma resulting in an elbow dislocation is a fall onto an outstretched hand and arm. When the hand hits the ground, the force is transmitted through the forearm to the elbow. This force pushes the elbow out of its socket.

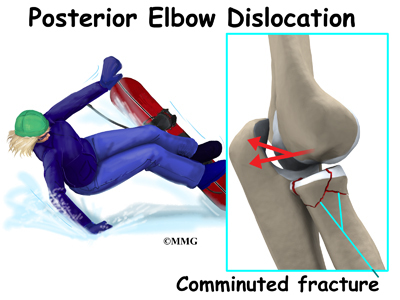

This can also result in a fracture/dislocation. About half of all elbow dislocations in teens and young adults occur as a result of a sports activity. The most common elbow dislocations are associated with sports such as gymnastics, cycling, roller-blading, or skateboarding.

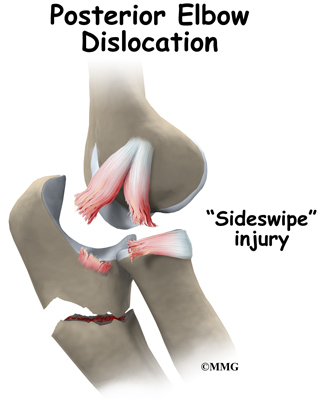

Dislocation can also occur from a sideswipe injury. This type of injury occurs when the driver of an automobile has the elbow out the open window during a car accident. The force of the impact causes a severe fracture-dislocation of the elbow.

Symptoms

What are the symptoms?

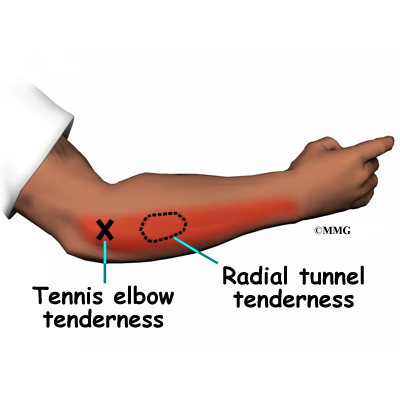

If the elbow is fully dislocated, it will look out of joint. There may be dimples or indentations of the skin over the dislocation where the bones have shifted position. Pain can be intense until the arm is relocated. The pain is often relieved immediately after the joint is put back in place. There may be some residual tenderness around the joint.

If ligaments or other soft tissues are torn, there can be swelling and bruising around the elbow. Bruising is not immediately obvious but appears several days after the injury. Injury to any of the three nerves that cross the elbow (median, ulnar, radial nerves) can cause neurologic symptoms such as numbness, tingling, and/or weakness of the forearm, wrist, and hand. If a bone fracture is also involved the fracture can cut or damage a nerve causing temporary or permanent paralysis.

Pain and an inability to straighten the elbow or pain when turning the hand the palm up (supination) is typical. There is often tenderness along the lateral aspect of the elbow (side of the elbow away from the body).

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose this condition?

The history and physical examination are probably the most important tools the physician uses to guide his or her diagnosis. Moving the elbow passively is painful, especially extension and supination. The doctor will check for any signs of injury to the nerves or blood vessels.

X-ray is the best way to look for dislocation or fracture-dislocation.

After the joint is relocated, other imaging studies may be ordered to look for damage to the joint cartilage, bone, ligaments, and other soft tissues. If bone detail is difficult to identify on an X-ray, a computed tomography (CT) scan may be done. If it is important to evaluate the ligaments, a magnetic resonance image (MRI) can be helpful.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

It is possible for the elbow to relocate by itself. This is more likely when there is a subluxation, rather than a complete dislocation. Sometimes the elbow can be reduced or put back in place by a trained medical person applying a quick motion to the forearm. There are several different methods used for manual (closed) reduction. Closed reduction refers to the fact that the elbow can be put back in joint without surgery. An open incision is not needed.

Manual reduction can be done in an emergency on site (e.g., at an athletic event or car accident) by a trained medical person but usually the procedure is done in a clinic or hospital setting. You would be given medications first to help with the pain.

Surgery

If there is too much swelling, it may be necessary to delay surgery for a few days up to a week. The elbow will be reduced right away and the arm immobilized while waiting for the swelling to subside.

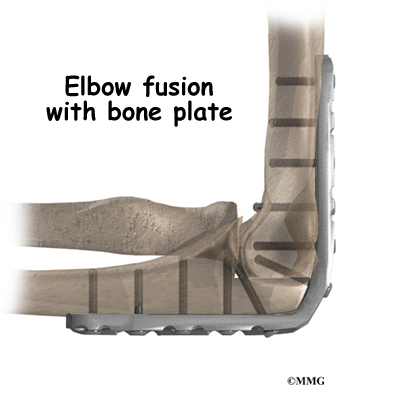

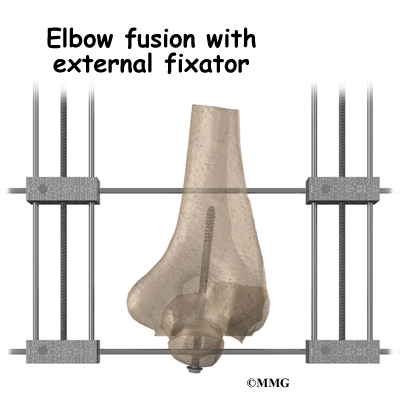

If there has been damage to the bones and/or ligaments, surgery may be needed to restore alignment and function. The type of surgery depends on the extent of the damage. Wires, pins, or even an external fixation device may be needed to hold everything together until healing occurs.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Simple elbow dislocations heal well with few (if any) problems. You may notice a slight loss of elbow motion, especially when trying to straighten the arm. This should not affect your overall motion and function. X-rays may be taken while the elbow heals. This will show if the bones of the elbow joint are healing in a reduced position with good alignment.

The arm may be immobilized for 10 to 14 days to allow the ligament to heal. Gentle range of motion may be allowed during that time but you should rely on your physician to advise you. Type of activities and movements allowed are determined according to the type of injury that’s present.

After immobilization, physical therapy may begin. The goal is to restore normal motion, joint proprioception (sense of position), and motor control. The program will progress to include strengthening.

Rehabilitation for the athlete includes sport-specific training is part of the rehab program. Your physical therapist will guide you through this process. Most athletes can resume sports participation three to six weeks after an elbow dislocation. The timing of return to sports depends on the type of sport (e.g., throwing sports may require a longer rehab). Dislocation of the dominant hand may require longer rehab before full motion and strength are restored.

Some athletes continue to wear a protective splint and/or use taping to stabilize the joint during the transition back into action. This can help protect the joint during motion and activity during the final phase of healing.

It’s best to avoid any further traction on the elbow until healing has occurred. Pulling a heavy door open, carrying a heavy purse, or lifting a heavy backpack are a few examples of activities and movements that put a traction force through the elbow. These kinds of movements should be avoided until healing occurs

After Surgery

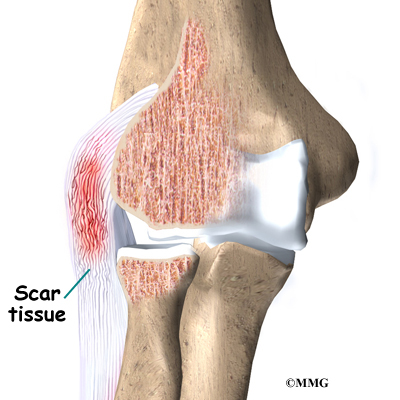

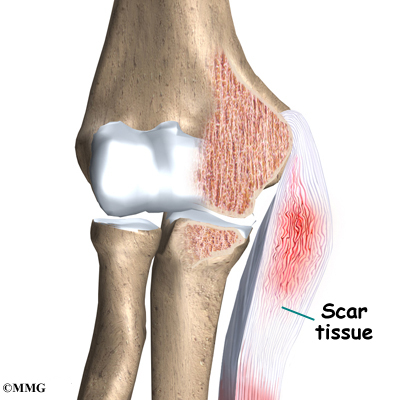

Post-operative immobilization is often required, especially for complex injuries. This could be a cast, dynamic splint, or postoperative range-of-motion (ROM) brace. The adjustable ROM brace is used to improve elbow motion gradually while allowing soft tissue healing. It helps minimize scar tissue formation and may contribute to fewer complications (such as arthritis) later on.

After immobilization, physical therapy may begin. The goal is to restore normal motion, joint proprioception (sense of position), and motor control. The program will progress to include strengthening. Rely on your doctor and therapist to guide you through the healing process.

As in conservative care, some athletes continue to wear a protective splint and/or use taping to stabilize the joint during the transition back into action. This can help protect the joint during motion and activity during the final phase of healing.

It’s best to avoid any further traction on the elbow until healing has occurred. Pulling a heavy door open, carrying a heavy purse, or lifting a heavy backpack are a few examples of activities and movements that put a traction force through the elbow. These kinds of movements should be avoided until healing occurs. Your doctor and/or therapist will advise you as you progress through the healing process.

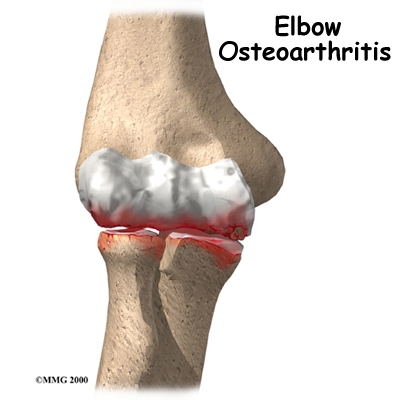

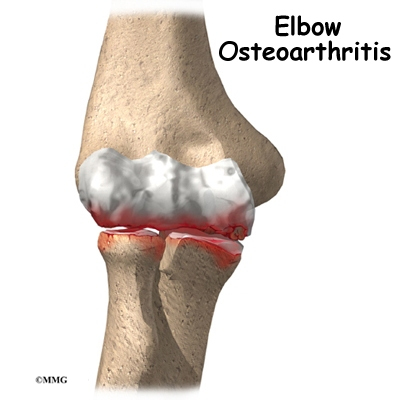

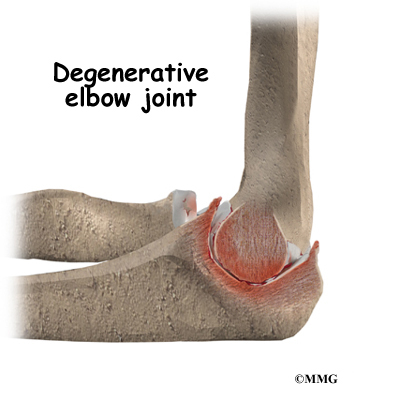

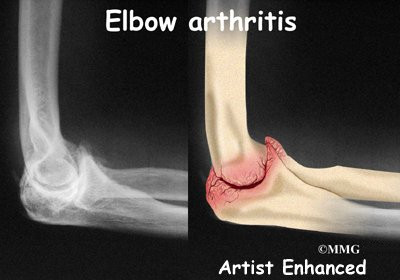

Scar tissue can cause a stiff elbow. Recurrent dislocation is also possible. If either of these problems develops, additional reconstructive surgery may be needed. For some patients, arthritis is a long-term result of elbow injury. This is more likely if there is a history of recurrent elbow dislocations.

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries

A Patient’s Guide to Ulnar Collateral Ligament Injuries

Introduction

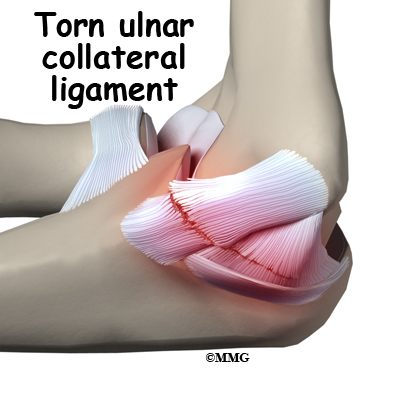

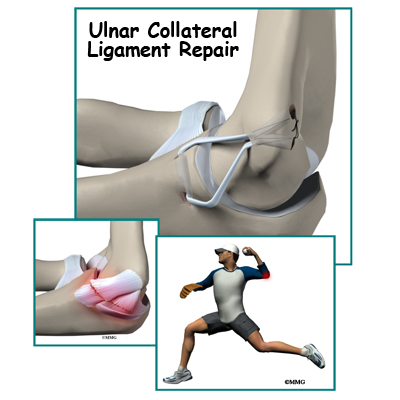

The ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) can become stretched, frayed or torn through the stress of repetitive throwing motions, causing ulnar collateral ligament injuries.

Professional pitchers have been the athletes treated most often for this problem. Javelin throwers and football, racquet sports, ice hockey, and water polo players have also been reported to injure the UCL. A fall on an outstretched arm can also lead to UCL rupture (often with elbow dislocation).

This guide will help you understand

- how the problem develops

- what causes this condition

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the elbow are affected?

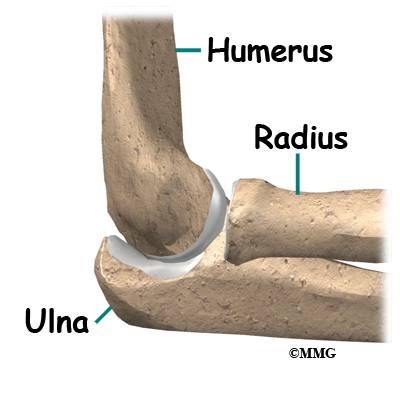

The bones of the elbow are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the ulna (the larger bone of the forearm, on the opposite side of the thumb), and the radius (the smaller bone of the forearm on the same side as the thumb).

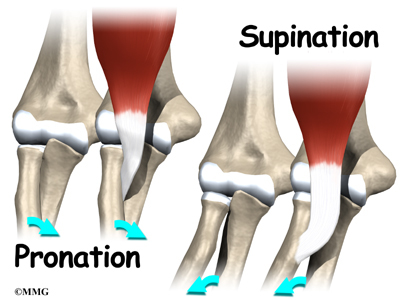

The elbow itself is essentially a hinge joint, meaning it bends and straightens like a hinge. But there is a second joint where the end of the radius (the radial head) meets the humerus. This joint is complicated because the radius has to rotate so that you can turn your hand palm up and palm down (pronation/supination). At the same time, it has to slide against the end of the humerus as the elbow bends and straightens.

The joint is even more complex because the radius has to slide against the ulna as it rotates the wrist as well. As a result, the end of the radius at the elbow is shaped like a smooth knob with a cup at the end to fit on the end of the humerus. The edges are also smooth where it glides against the ulna.

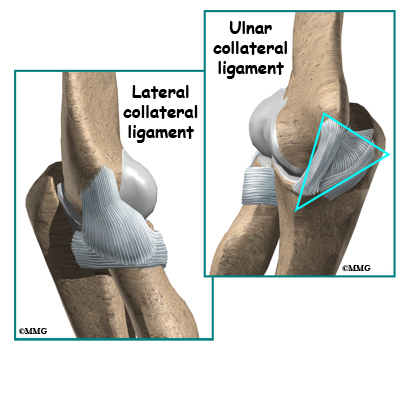

There are several important ligaments in the elbow. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. The ligaments around a joint usually combine together to form a joint capsule. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint and contains lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

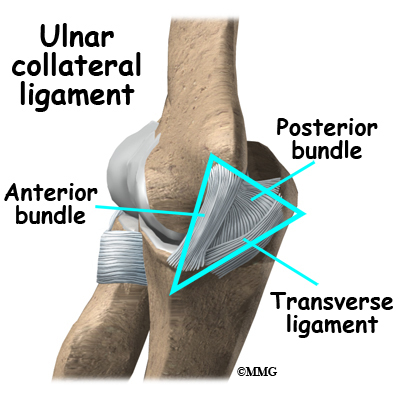

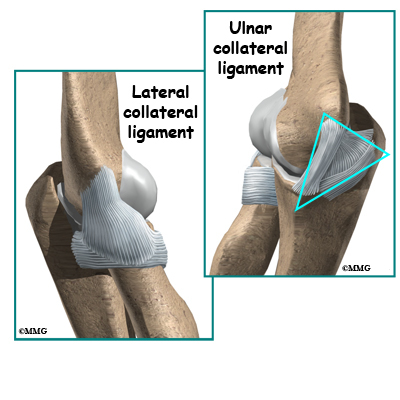

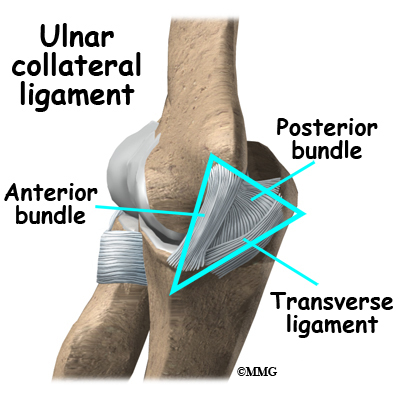

In the elbow, two of the most important ligaments are the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and the lateral collateral ligament. The UCL is also known as the medial collateral ligament. The ulnar collateral ligament is on the medial (the side of the elbow that’s next to the body) side of the elbow, and the lateral collateral is on the outside. The ulnar collateral ligament is a thick band of ligamentous tissue that forms a triangular shape along the medial elbow. It has an anterior bundle, posterior bundle, and a thinner, transverse ligament.

Together these two ligaments, the ulnar (or medial) collateral and the lateral collateral, connect the humerus to the ulna and keep it tightly in place as it slides through the groove at the end of the humerus. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the elbow. They can be torn when there is an injury or dislocation of the elbow. If they do not heal correctly the elbow can be too loose or unstable. The ulnar collateral ligament can also be damaged by overuse and repetitive stress, such as the throwing motion.

Causes

What causes ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) injuries?

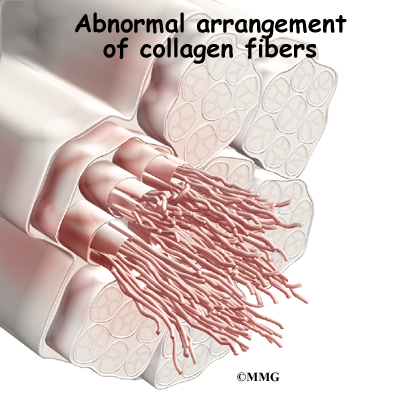

The ulnar collateral ligament can become stretched, frayed or torn through the stress of repetitive throwing motions. If the force on the soft tissues is greater than the tensile strength of the structure, then tiny tears of the ligament can develop. Months (and even years) of throwing hard cause a process of microtears, degeneration, and finally, rupture of the ligament. The dominant arm is affected most often. Eventually the weakened tendon my rupture completely causing a pop and immediate pain. The athlete may report the injury occurred during a single throw, but the reality is usually that the ligament simply finally became weakened to the point that it finally ruptured.

Professional pitchers have been the athletes treated most often for this problem. Javelin throwers and football, racquet sports, ice hockey, and water polo players have also been reported to injure the UCL. A fall on an outstretched arm can also lead to UCL rupture (often with elbow dislocation).

However, the general profile associated with this injury may be changing. Today, more and more children ages 10 to 18 are affected. Longer seasons with extended practice time and more tournaments increase the risk of UCL injury. Throwing volume, pitch type, and throwing mechanics can all contribute to the problem.

Children have their own unique risk factor in that they have an open growth plate in the elbow called the medial epicondylar physis. Force along the inside of the elbow during throwing is more likely to cause failure at the area of the growth plate than at the UCL. This injury is often termed Little League Elbow. Reconstruction of the UCL may not be needed in this age group unless the injury to the UCL occurs after the growth plate is closed. Sometimes the ligament avulses or pulls away, taking a piece of the growth plate with it. When the condition has been present for some time, the ligament is not all that may be damaged. The entire elbow joint is at risk due to the abnormal forces caused by the repetitive stress injury.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Adolescent Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

Symptoms

What does the condition feel like?

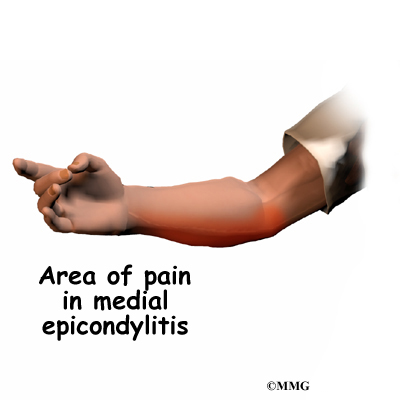

Pain along the inside of the elbow is the main symptom of this condition. Throwing athletes report it occurs most often during the acceleration phase of throwing. If there are loose fragments or uneven joint surfaces, you may also notice popping, catching, or grinding.

Sometimes swelling can be seen along the inside of the elbow. If the ligament was ruptured, there may be bruising in the same area. Some patients have a slight loss of elbow motion. Closing the hand and clenching the fist reproduces the painful symptoms.

Sometimes swelling can be seen along the inside of the elbow. If the ligament was ruptured, there may be bruising in the same area. Some patients have a slight loss of elbow motion. Closing the hand and clenching the fist reproduces the painful symptoms.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

The diagnosis is based on your history and symptoms. Your physician will complete an examination of the shoulder and elbow, performing specific tests to look for areas of tightness or laxity (looseness). Most patients will report tenderness along the inside of the elbow to palpation of the UCL ligament.

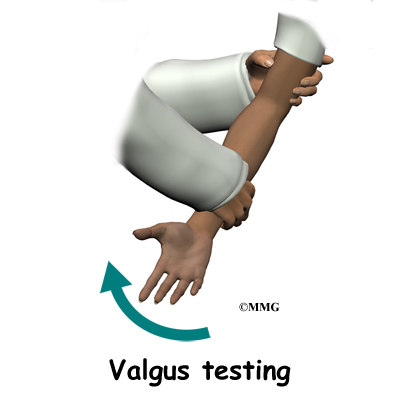

Valgus stress tests are done at the elbow to test for joint stability. The examiner places force toward the inside of the elbow as the joint is moved from a position of slight flexion into full extension. Too much motion or opening of the joint at the medial joint line called gapping may be observed or felt by palpation. The examiner may also feel the crepitation (popping, crunching) as the joint moves.

Standard X-rays are taken to look for bone spurs, loose fragments, or calcification in the ulnar collateral ligament. If the joint is gapping enough to sublux (partially dislocate), valgus stress radiographs may be taken.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with contrast dye is used to diagnose ligamentous rupture. The test doesn’t always show a problem when there is one. This is called a false-negative result. Ultrasound and CT scans may be helpful. Some surgeons prefer to use arthroscopy to make the final diagnosis. The presence and severity of valgus gapping can be confirmed. Studies using these more advanced test methods to diagnose UCL injuries are being done. More data is needed before they become routine in the diagnosis of UCL injuries.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Many athletes with elbow instability from UCL injury can be treated successfully with rehabilitation and without invasive procedures. At first, symptoms may be treated with rest and/or activity modification (fewer pitches per game, per practice, per day). The athlete’s posture, strength, and release of the ball must be analyzed and corrected. The use of curve balls should be avoided during the early phases of rehabilitation.

Antiinflammatory drugs and analgesics may be used to reduce pain and inflammation. Icing may help but must be used with caution. Too much cold can cause a worsening of the swelling as the body sends more blood to the area to warm things up. And cold can be an irritant to the already damaged (and irritated) nerve.

Many athletes are able to return to play without further treatment. If conservative (nonoperative) care does not change the picture, then surgery may be needed.

Surgery

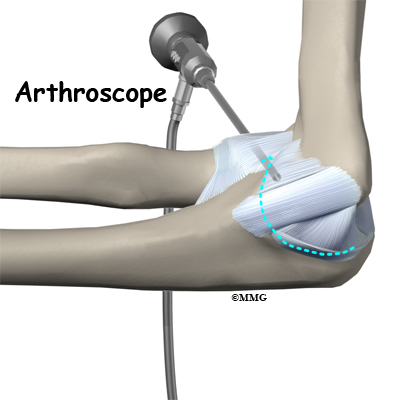

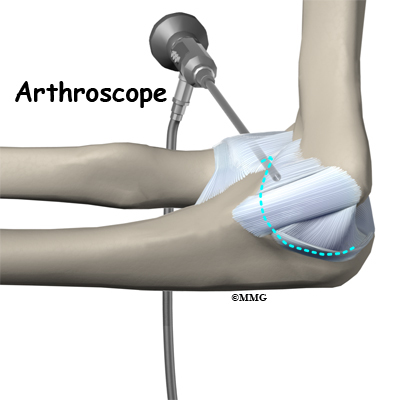

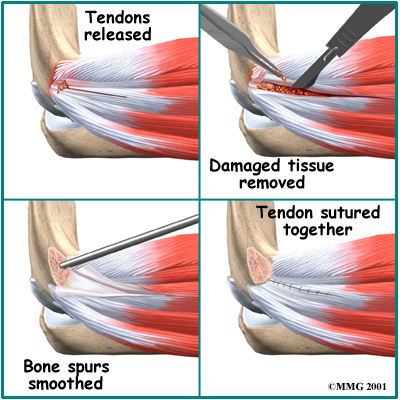

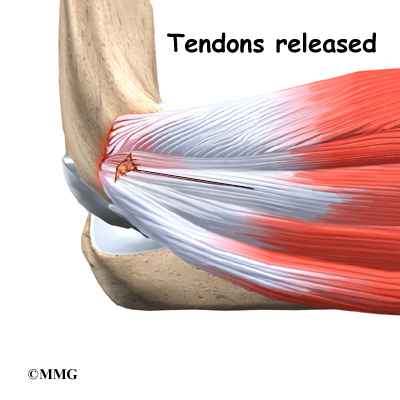

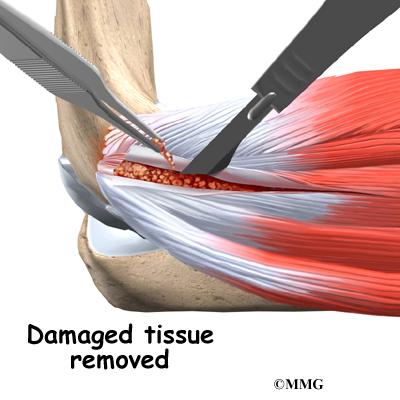

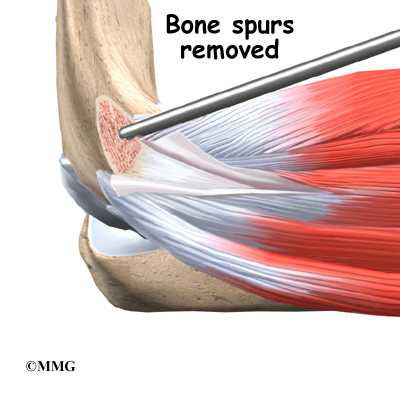

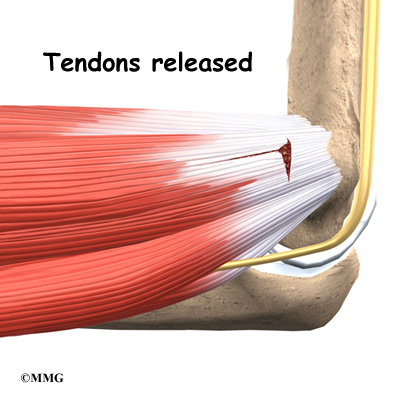

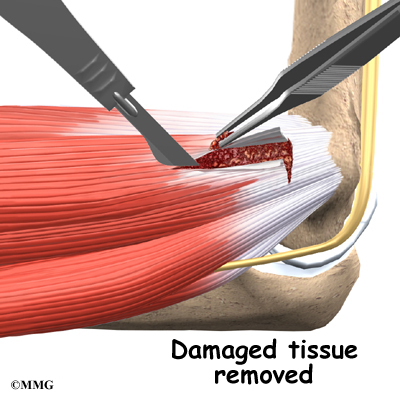

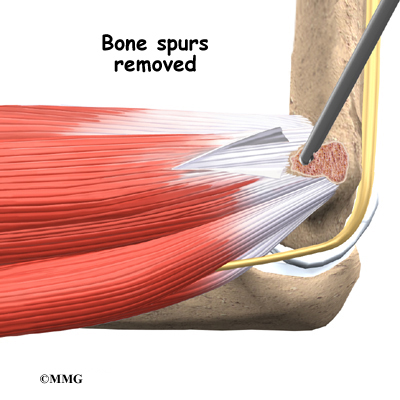

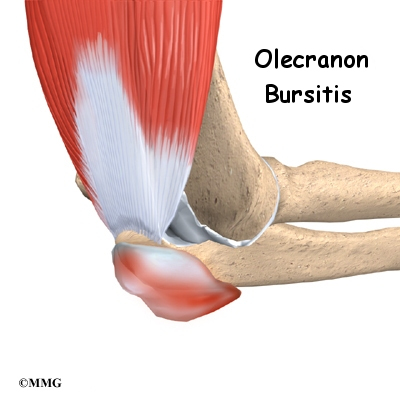

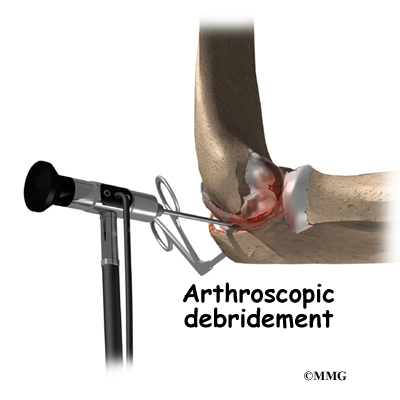

When the condition fails to respond to conservative care described above, surgery may be indicated. If pain is the primary symptom and there is no evidence that the elbow joint is grossly unstable, the surgeon may use an arthroscope (a tiny fiber-optic TV camera) to look inside the elbow and see the condition of the joint and the soft tissues. It may be possible to debride any tissue fragments or frayed edges. During debridement, the surgeon carefully cleans the area by removing any dead or damaged tissue. Any bone spurs or areas of calcium build-up are also removed.

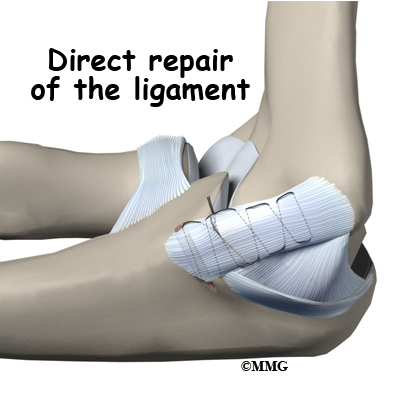

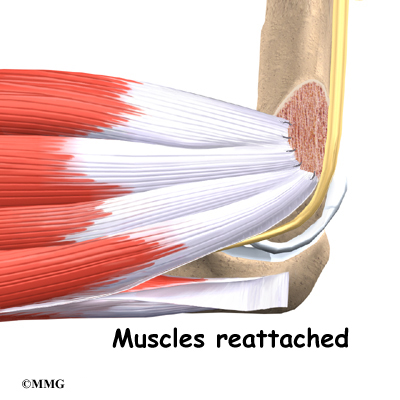

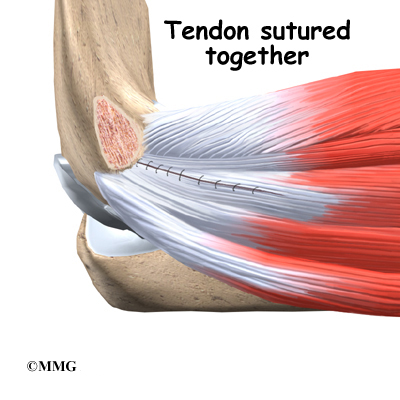

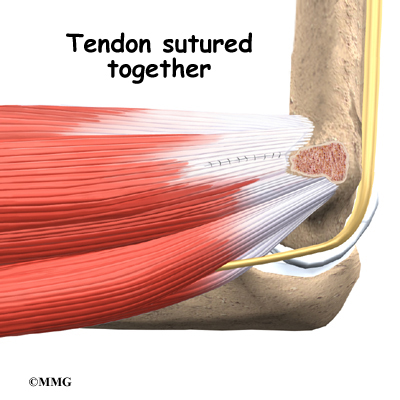

If the ulnar collateral ligament has been injured acutely due to a fall on the outstretched arm, a direct repair of the ligament may be possible. If the ligament has pulled off the bone, it may be reattached with sutures through holes drilled in the bone. If the ligament is damaged by constant overuse and is not strong enough to restore stability to the elbow joint if it is simply re-attached or repaired, then the ligament must be replaced with a new ligament. This is termed a ligament reconstruction. During a reconstruction, the ulnar collateral ligament along the medial (inside) of the elbow is replaced with a tendon graft harvested from somewhere else in the body (autograft). One common technique used to replace the damaged ulnar collateral ligament is called the docking technique.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

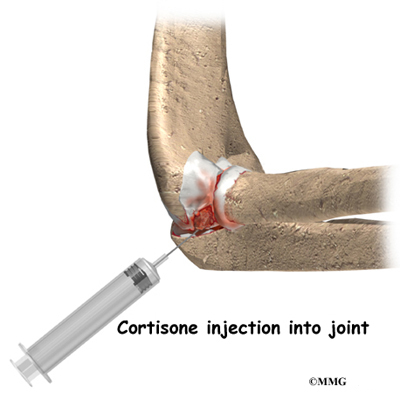

Other modalities such as electrical stimulation and ultrasound with cortisone (called phonophoresis) may be used by a physical therapist when needed. Steroid injections are not usually recommended for this condition.

The athlete will work with the physical therapist to develop a daily program of stretching and strengthening. Stretching exercises for the muscles of the forearm are included. A strengthening program for the entire elbow/arm complex will be prescribed. High repetition, low weight exercise training is used to increase endurance without placing additional stress across the joint.

The therapist will also address any problems with flexibility, strength, and conditioning at the shoulder. Plyometric strengthening of the entire arm starts with the forearm muscles (flexors and pronators) and progresses to include the biceps, triceps, and rotator cuff of the upper arm. Plyometrics refers to training the nerves to fire quickly and the muscles to contract strong and fast. Plyometrics help develop explosive movements to improve muscular power and force. The goal is to increase the speed of the pitch (or throw for other throwing athletes).

After Surgery

Arthroscopic Debridement

Gentle range of motion exercises are started right away. Full motion is restored as the pain and swelling resolve. Elbow strengthening exercises are begun within the first few days to week after the procedure. A rehabilitation program is started and progressed, including a gradual throwing program. Full sports participation can be anticipated within one to three months.

Repair or Reconstruction

The postoperative program is the same for repairs or reconstruction. At first your arm will be immobilized in a bulky dressing.

You will be referred to a physical therapist to begin a rehabilitation program.

Gentle handgrip and shoulder and wrist mobilization exercises are allowed right away after surgery. Postoperative immobilization is discontinued in seven to 10 days at which time active range of motion for the elbow is started. Your surgeon may want you to wear a special hinged brace to protect the elbow.

Your therapist will instruct you in the active range of motion exercises to be done daily. Strengthening exercises for the entire upper quadrant (shoulder, arm, wrist, and hand) are included in the post-operative program. Specific strengthening exercises to help the athlete prepare for his or her particular sport begin around four months post-op. Up until this time, any stress to the medial elbow is avoided.

See also: Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction or Tommy John Surgery

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction (Tommy John Surgery)

A Patient’s Guide to Ulnar Collateral Ligament Reconstruction (Tommy John Surgery)

Introduction

The doctors call it a UCLR ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Baseball players and fans call it Tommy John surgery — named after the pitcher (Los Angeles Dodgers) who was the first to have the surgery in 1974. It is one of the major advancements in sports medicine in the last quarter century.

This guide will help you understand:

- what your surgeon hopes to achieve

- how do I prepare for this procedure

- what happens during the procedure

- what to expect as you recover

Anatomy

What’s the normal anatomy of the elbow?

The bones of the elbow are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the ulna (the larger bone of the forearm, on the opposite side of the thumb), and the radius (the smaller bone of the forearm on the same side as the thumb).

There are several important ligaments in the elbow. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. The ligaments around a joint usually combine together to form a joint capsule. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint and contains lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

In the elbow, two of the most important ligaments are the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) and the lateral collateral ligament. The UCL is also known as the medial collateral ligament. The ulnar collateral ligament is on the medial (the side of the elbow that’s next to the body) side of the elbow, and the lateral collateral is on the outside. The ulnar collateral ligament is a thick band of ligamentous tissue that forms a triangular shape along the medial elbow. It has an anterior bundle, posterior bundle, and a thinner, transverse ligament.

Together these two ligaments, the ulnar (or medial) collateral and the lateral collateral, connect the humerus to the ulna and keep it tightly in place as it slides through the groove at the end of the humerus. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the elbow. They can be torn when there is an injury or dislocation of the elbow. If they do not heal correctly the elbow can be too loose or unstable. The ulnar collateral ligament can also be damaged by overuse and repetitive stress, such as the throwing motion.

Rationale

What does my surgeon hope to achieve?

Surgical treatment is designed to restore medial stability of the elbow. Full return to previous activities is the main goal. This is especially true for those athletes who want to remain active and competitive in sports. Many throwing athletes who develop this condition have pain in the elbow during and after throwing activities. They may also develop numbness and tingling in the hand due to stretching of the ulnar nerve at the elbow. Successful treatment of the condition should improve or eliminate these symptoms.

Who can benefit from this procedure?

Throwing athletes (especially baseball pitchers) at the college and professional level are affected most often by this injury requiring surgery. Minor league athletes and younger sports participants may also develop this injury requiring surgical care. Anyone with this injury who has not benefited (gotten better) with conservative care is a candidate for surgery.

Preparation

How should I prepare for surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery must be made jointly by you and your surgeon. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during the operation?

Reconstruction

If you are having problems that may be coming from inside the joint, such as arthritis and loose bodies, your surgeon may perform an arthroscopy before the actual reconstruction procedure is done. During this procedure, a small TV camera is inserted into the elbow joint through two or three small (1/4 inch) incisions. Using special instruments your surgeon will be able to evaluate the joint, remove any loose bodies and bone spurs that may be causing problems. Arthroscopy is not always necessary.

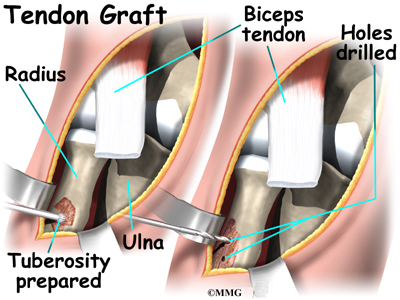

The reconstruction is performed through an incision on the medial (inside) side of the elbow joint. The damaged ulnar collateral ligament along the medial side of the elbow is replaced with a tendon harvested from somewhere else in the body. The tendon graft can come from the patient’s own forearm, hamstring, knee, or foot. This is called an autograft.

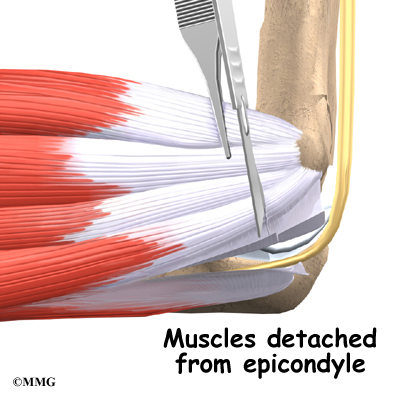

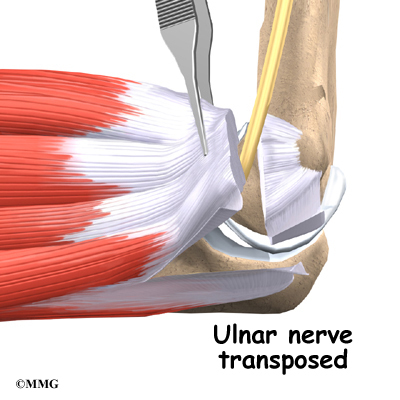

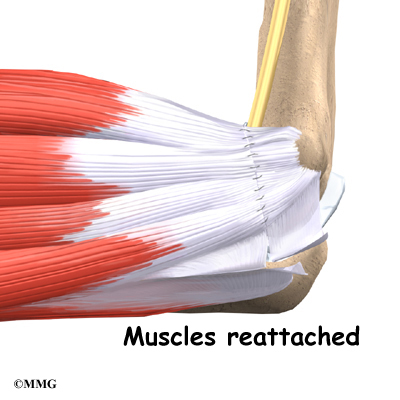

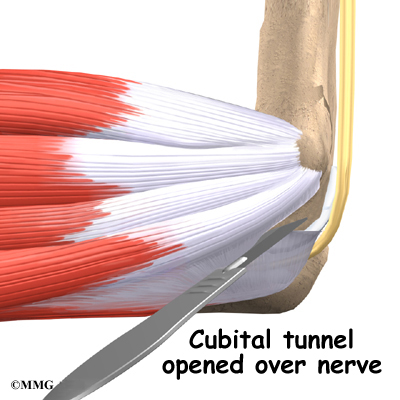

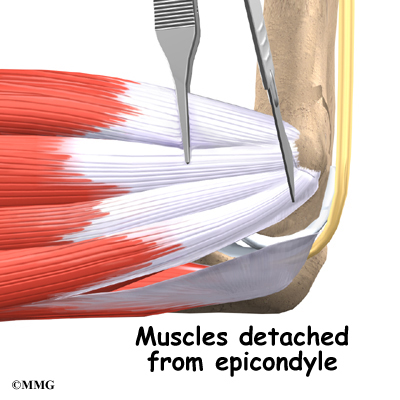

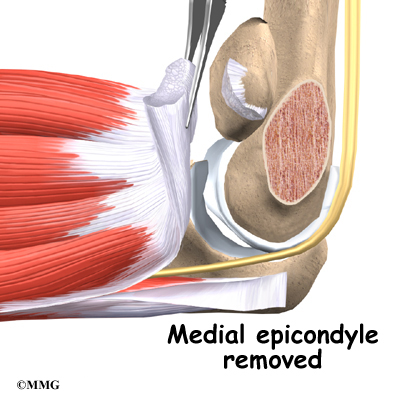

Over the years the way that surgeons perform this operation have improved. In the early days, the muscles on the inside of the elbow joint and forearm (the flexor muscles) were completely detached from the humerus and the ulnar nerve was re-routed from its normal position in the cubital tunnel on the back side of the elbow. This was done to be able to see the joint and protect the nerve. As surgeons have understood this problem more completely, these two parts of the operation have been eliminated. Now, the flexor muscles are not detached, but are split and retracted to allow the surgeon to see the areas of the elbow joint required to perform the operation successfully. The ulnar nerve is re-routed only if the patient was having symptoms of ulnar nerve damage before the operation. These improvements have resulted in a less invasive procedure with a decreased rate of complications.

One common technique used to replace the damaged ulnar collateral ligament is called the docking technique. The surgeon drills two holes in the ulna and three in the medial epicondyle (the small bump of bone on the inside of the elbow at the end of the humerus). The two holes in the ulna form a tunnel that the tendon graft will be looped through. The three holes in the medial epicondyle form a triangle. The bottom hole will be bigger than the top two holes, so that the surgeon can slide the end of the tendon graft into the bottom hole. The two top holes are used to pull the tendon graft into the tunnel using sutures that are attached to the graft and threaded through the two holes.

After the tendon is harvested, sutures are attached to both ends. The tendon is looped through the lower tunnel formed in the ulna, and stretched across the elbow joint. The two sutures attached to the ends of the graft are threaded into the larger bottom tunnel in the medial epicondyle and each is threaded out one of the upper, smaller holes.

Using these two sutures, the surgeon pulls the end of the graft farther into the upper tunnel until the amount of tension is correct to hold the joint in position. The surgeon carefully puts the elbow through its full arc of motion and readjusts the tension on the sutures until he is satisfied that the proper ligamentous tension is restored. The two sutures are tied together to hold the tendon graft in that position.

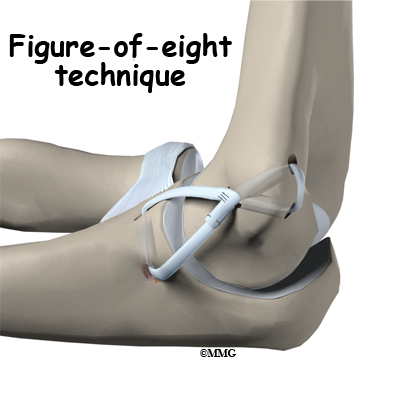

Another common technique to reconstruct the ulnar collateral ligament is the figure of eight technique. In this technique, the tendon graft is threaded through two pairs of holes – two drilled in the medial epicondye and two in the ulna. The graft is looped through the holes in a figure of eight fashion. The two ends of the tendon are sutured to the tendon itself.

If there is any concern that the ulnar nerve has been stretched and damaged due to the instability (as mentioned above), it may be re-routed so that it runs in front of the elbow joint rather than through the cubital tunnel in the back of the elbow. The incision is sutured together and the elbow is placed in a large bandage and splint.

There are several newer techniques being developed that hopefully will make the procedure even less invasive while retaining the success that the docking technique has enjoyed.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all surgical procedures, complications can occur. This topic doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications are

- anesthesia complications

- infection

- nerve or blood vessel damage

Anesthesia

Problems can arise when the anesthesia given during surgery causes a reaction with other drugs the patient is taking. In rare cases, a patient may have problems with the anesthesia itself. In addition, anesthesia can affect lung function because the lungs don’t expand as well while a person is under anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Infection

Any operation carries a small risk of infection. You may be given antibiotics before the operation to reduce the risk of infection. If an infection occurs, you will most likely need more antibiotics to cure it.

Nerve or Blood Vessel Damage

Because the operation is performed so close to the nerves and vessels, it is possible to injure them during surgery. All of the nerves that travel down the arm pass across the elbow. The ulnar nerve is especially at risk for damage. Problems such as pain, numbness, and weakness in the arm and hand can be the consequences of nerve scarring, entrapment, or traction injury from the original trauma or from the procedure.

This condition is called a neuropathy. It may be temporary with gradual resolution of symptoms over a period of many months. If it doesn’t resolve on its own or with physical therapy, further surgery may be needed. In a small number of cases, this complication is permanent.

Studies show that up to half of the patients treated by ligament reconstruction are left with a loss of full motion. The main problem is a five to 10 degree loss of extension (the elbow doesn’t straighten all the way). This deformity does not affect strength or function. Earlier, more aggressive rehab may restore motion but at the risk of impaired healing of the graft.

Long-term complications can include chronic pain with throwing and chronic instability of the elbow.

After Surgery

What should I expect as I recover?

Repair or Reconstruction

The postoperative program is the same for repairs or reconstruction. At first your arm will be immobilized in a bulky dressing and a posterior splint for the first 10 days. It holds the elbow in a position of 90 degrees of flexion and neutral forearm rotation while leaving the wrist free to move. If non-absorbable sutures are used to close the incision, you may need these removed in 10 days.

You’ll have about a four-inch long incision along the inside of your elbow. There may be some discomfort after surgery. Your surgeon can give you pain medicine to control the discomfort. You should keep your elbow elevated above the level of your heart for several days to avoid swelling and throbbing. Keep your elbow propped up on a stack of pillows when sleeping or sitting.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect during my rehabilitation?

Gentle hand grip and shoulder and wrist mobilization exercises are allowed right away after surgery. Postoperative immobilization is discontinued in seven to 10 days at which time active range of motion for the elbow are started. Your surgeon may want you to wear a special hinged brace to protect the elbow.

Your therapist will instruct you in the active range of motion exercises to be done daily. Strengthening exercises for the entire upper quadrant (shoulder, arm, wrist, and hand) are included in the post-operative program. Specific strengthening exercises to help the athlete prepare for his or her particular sport begin around four months post-op. Up until this time, any stress to the medial elbow is avoided.

With careful adherence to the rehab program and completing the exercises daily, pitchers can get their full range of motion back in six to eight weeks. The program will progress to strength training with weight exercises. For the next four months, they can increase the weight they use and start doing exercises that emphasize all parts of their arm.

Flexibility, conditioning, coordination, and strengthening are part of the daily program. You may use ice after throwing sessions to help control inflammation. Plyometric exercises are used throughout the training period. An aerobic portion of the exercise program is also advised to help the athlete return to sports at the same level (or even higher level) as before the surgery. Good, overall physical condition is important to prevent injury as the athlete returns to sports activity.

At times in your rehab and recovery, you may find it necessary to move back to a previous level of training if symptoms of pain and swelling recur. Your therapist will guide you through the advancement (and regression) of your program. Additional training to restore normal joint proprioception (sense of joint position) and proper throwing mechanics is also provided.

Based on long-term studies of athletes over the years, the chances of a complete recovery after surgery are estimated at 85 to 90 percent. The process of rehabilitation to return to a level of playing equal to before the injury takes about a year for pitchers and about six months for position players.

The most often used criteria for resuming full (competitive) sports participation include 1) no pain with throwing, 2) full shoulder and elbow range of motion, 3) normal forearm strength, and 4) good throwing biomechanics.

The tendon graft is very weak immediately after the surgery. Transforming a tendon into a functioning ligament requires a very gradual rebuilding process. Athletes are encouraged to go slowly and not test the limits of the graft. The key to a successful UCLR (Tommy John) is to rehab for a long-term career, not to try for shortcuts during the first year of recovery.

Distal Biceps Rupture

A Patient’s Guide to Distal Biceps Rupture

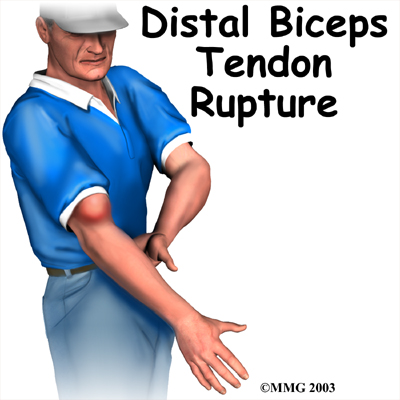

Introduction

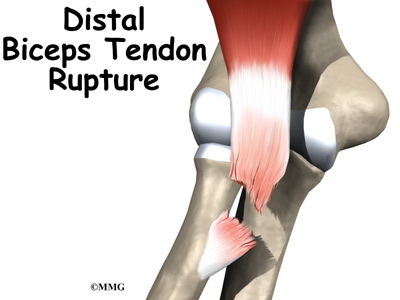

A distal biceps rupture occurs when the tendon attaching the biceps muscle to the elbow is torn from the bone. This injury occurs mainly in middle-aged men during heavy work or lifting. A distal biceps rupture is rare compared to ruptures where the top of the biceps connects at the shoulder. Distal biceps ruptures make up only three percent of all biceps tendon ruptures.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the elbow are affected

- the causes of distal biceps rupture

- ways to treat this problem

Anatomy

What parts of the elbow are affected?

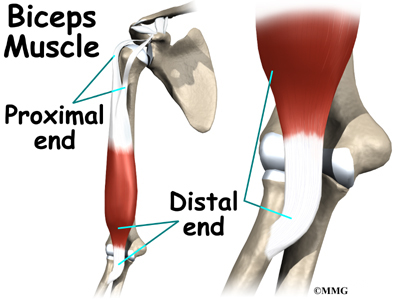

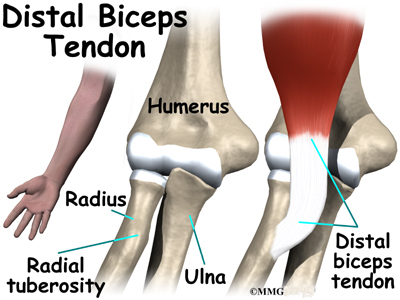

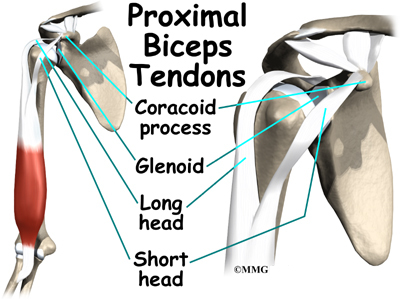

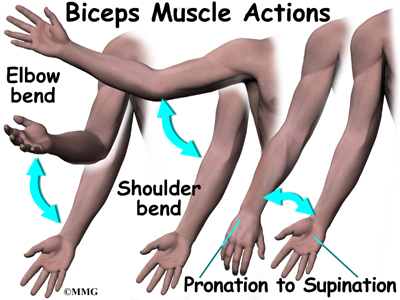

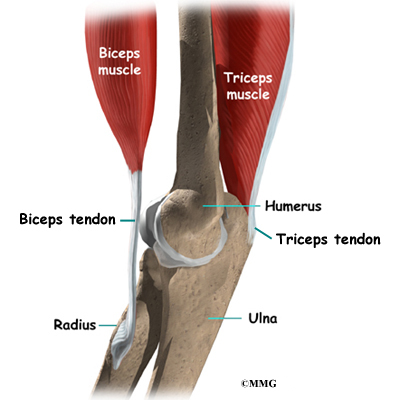

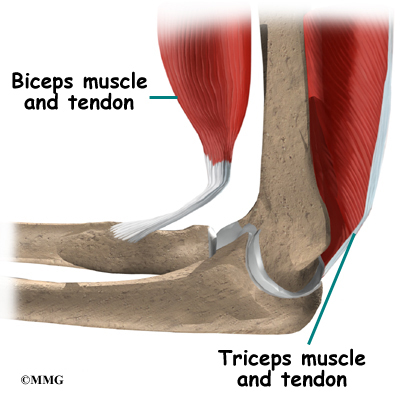

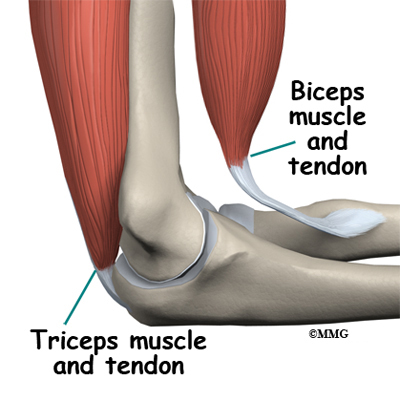

The biceps muscle goes from the shoulder to the elbow on the front of the upper arm. Tendons attach muscles to bone. Two separate tendons connect the upper part of the biceps muscle to the shoulder. One tendon connects the lower end of the biceps to the elbow.

The lower biceps tendon is called the distal biceps tendon. The word distal means that the tendon is further down the arm. The upper two tendons of the biceps are called the proximal biceps tendons, because they are closer to the top of the arm.

The distal biceps tendon attaches to a small bump on the radius bone of the forearm. This small bony bump is called the radial tuberosity. The radius is the smaller of the two bones between the elbow and the wrist that make up the forearm. The radius goes from the outside edge of the elbow to the thumb side of the wrist. It parallels the larger bone of the forearm, the ulna. The ulna goes from the inside edge of the elbow to the wrist.

The upper (proximal) end of the biceps has two attachments to the shoulder. The main attachment is the long head of the biceps. It connects the biceps muscle to the top of the shoulder socket, called the glenoid. The short head of the biceps angles up and in to its attachment on the corocoid process of the shoulder blade. The corocoid process is a small bony knob in the front of the shoulder.

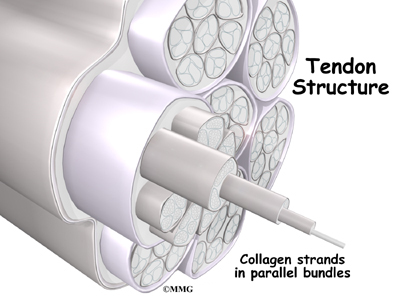

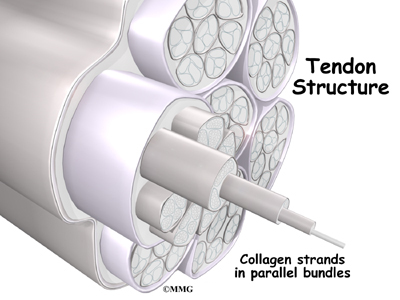

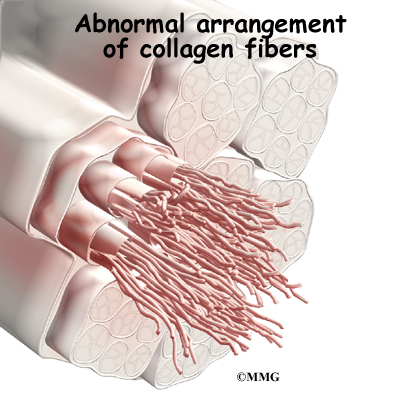

Tendons are made up of strands of a material called collagen. The collagen strands are lined up in bundles next to each other.

Because the collagen strands in tendons are lined up, tendons have high tensile strength. This means they can withstand high forces that pull on both ends of the tendon. When muscles contract, they pull on one end of the tendon. The other end of the tendon pulls on the bone, causing the bone to move.

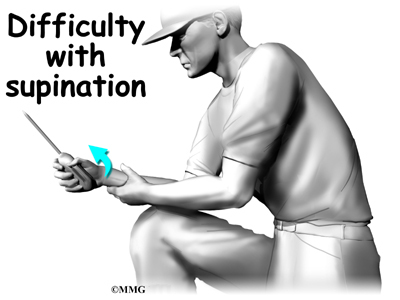

Contracting the biceps muscle can bend the elbow upward. The biceps can also help flex the shoulder, raising the arm up. And the biceps can rotate, or twist, the forearm in a way that points the palm of the hand up. This movement is called supination. Supination positions the hand as if you were carrying a tray.

Causes

Why did I develop a rupture of the distal biceps?

The most common cause of a distal biceps rupture happens when a middle-aged man lifts a box or other heavy item with his elbows bent. Often the load is heavier than expected, or the load may shift unexpectedly during the lift. This forces the elbow to straighten, even though the biceps muscle is working hard to keep the elbow bent. The biceps muscle contracts extra hard to help handle the load. As tension on the muscle and tendon increases, the distal biceps tendon snaps or tears where it connects to the radius.

Symptoms

What does a ruptured distal biceps feel like?

When the distal biceps tendon ruptures, it usually sounds and feels like a pop directly in front of the elbow. At first the pain is intense. The pain often subsides quickly after a complete rupture because tension is immediately taken off the pain sensors in the tendon. Swelling and bruising in front of the elbow usually develop shortly after the pop. The biceps may appear to have balled up near the elbow. The arm often feels weak with attempts to bend the elbow, lift the shoulder, or twist the forearm into supination (palm up).

The distal biceps tendon sometimes tears only part of the way. When this happens, a pop may not be felt or heard. Instead, the area in front of the elbow may simply be painful, and the arm may feel weak with the same arm movements that are affected in a complete rupture.

Diagnosis

How can my doctor be sure I have ruptured the distal biceps?

An early diagnosis is best. If surgery is needed, people who’ve ruptured their distal biceps tendon usually have better results when surgery is done soon after the injury.

Your doctor will first take a detailed medical history. You will need to answer questions about your pain, how your pain affects you, your regular activities, and past injuries to your elbow.

The physical exam is often most helpful in diagnosing a rupture of the distal biceps tendon. Your doctor may position your elbow and forearm to see which movements are painful and weak. By feeling the muscle and tendon, your doctor can often tell if the tendon has ruptured off the bone.

X-rays may be ordered. X-rays are mainly used to find out if there are other injuries in the elbow. Plain X-rays do not show soft tissues like tendons. They will not show a distal biceps rupture unless a small piece of bone got pulled off the radius as the tendon ruptured. This type of injury is called an avulsion fracture.

Your doctor may also order a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan to see if the biceps tendon is only partially torn or if the tendon fully ruptured. An MRI is a special imaging test that uses magnetic waves to create pictures of the elbow in slices. The MRI can also show if there are other problems in the elbow.

Treatment

What can I do to treat this problem?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Many doctors prefer to treat distal biceps tendon ruptures with surgery. Nonsurgical treatments are usually only used for people who do minimal activities and require minimal arm strength. Nonsurgical treatments are only used if arm weakness, fatigue, and mild deformity aren’t an issue. If you are an older individual who can tolerate loss of strength, or if the injury occurs in your nondominanat arm, you and your doctor may decide that surgery is not necessary.

Not having surgery often results in significant loss of strength. Flexion of the elbow is somewhat affected, but supination (which is the motion of twisting the forearm, such as when you use a screwdriver) can be very affected. A distal biceps rupture that is not repaired reduces supination strength by about 50 percent.

Nonsurgical measures may include a sling to rest the elbow. Patients may be given anti-inflammatory medicine to help ease pain and swelling and get them back to activities sooner. These medications include common over-the-counter drugs such as ibuprofen.

Your doctor may have you work with a physical or occupational therapist. At first, your therapist will give you tips how to rest your elbow and how to do your activities without putting extra strain on the joint. Your therapist may apply ice and electrical stimulation to ease pain. Exercises are used to gradually strengthen other muscles that can help do the work of a normal biceps muscle.

Surgery

People who need normal arm strength get best results with surgery to reconnect the tendon right away. Surgery is needed to avoid tendon retraction. When the tendon has been completely ruptured, contraction of the biceps muscle pulls the tendon further up the arm. When the tendon recoils from its original attachment and remains there for a very long time, the surgery becomes harder, and the results of surgery are not as good.

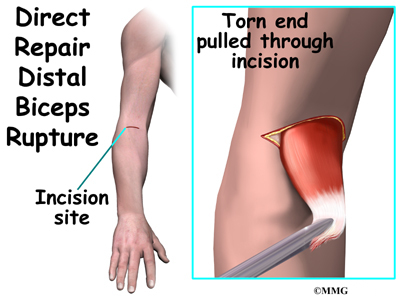

Direct Repair

Direct repair surgery is commonly done soon after the rupture. Doing a direct repair soon after the injury lessens the risk of tendon retraction.

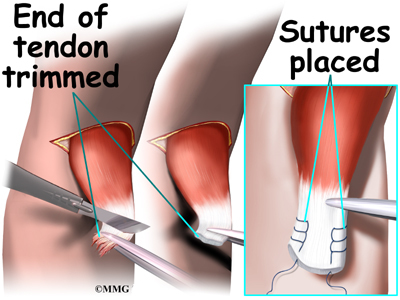

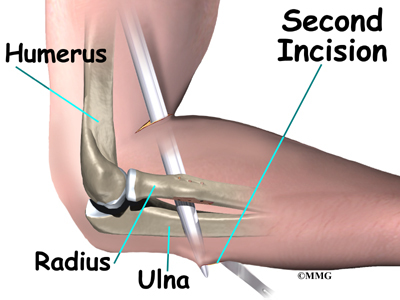

In a direct repair, the surgeon begins by making a small incision across the arm, just above the elbow. Forceps are inserted up into this incision to grasp the free end of the ruptured biceps tendon. The surgeon pulls on the forceps to slide the tendon through the incision. Attention is given to the free end of the tendon. A scalpel is used to slice off the damaged and degenerated end. Sutures are then crisscrossed through the bottom inch of the distal biceps tendon.

A curved instrument is passed through the incision and directly between the radius and ulna bones. The surgeon pushes the instrument through this space, puncturing the muscles and soft tissues. The surgeon feels the back side of the forearm for the spot where the instrument is protruding. A second incision is made at this spot.

The original attachment on the radius, the radial tuberosity, is prepared. An instrument called a burr shaves off the surface of the tuberosity. The burr is then used to create a small cavity in the bone for the tendon to fit inside. Three small holes are drilled into the top of the rim of bone to secure the sutures.

The tendon is passed between the radius and ulna, exiting through the second incision that was made on the back of the forearm. The sutures are threaded into the three holes that were drilled into the rim of the radial tuberosity. The surgeon ties the sutures, securing the newly reattached biceps tendon. When the surgeon is satisfied with the repair, the skin incisions are closed, and the elbow is placed either in a cast or a range-of-motion brace.

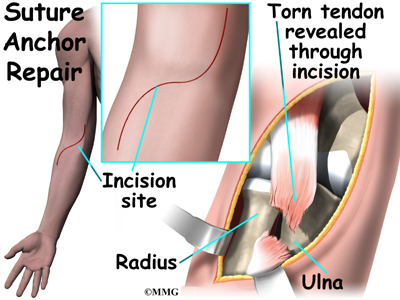

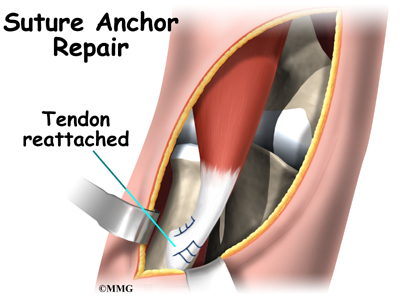

Suture Anchor Method

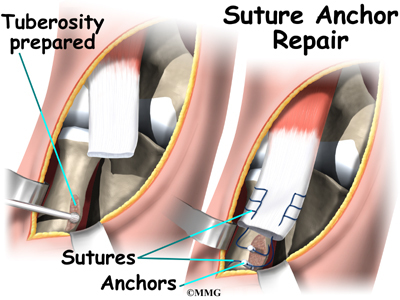

A new method of anchoring the torn tendon to the radius is gaining popularity. This method uses special anchors, called suture anchors, to fix the tendon in place. The procedure requires only one incision and appears to lessen the risk of myositis ossificans. Myositis ossificans is an abnormal healing response that causes bone to form in the muscles and soft tissues.

The surgeon begins by making a single incision across the arm, just above the elbow. Along the outside edge of the arm, the incision curves and goes upward for a short distance. The skin and underlying tissues are pulled back using retractors. This reveals the front of the lower biceps muscle and allows the surgeon to avoid injuring nearby nerves and arteries. The fascia (connective covering over the muscle) is cut away so the surgeon can see the radial tuberosity.

The original attachment on the radius, the radial tuberosity, is prepared by shaving off the surface with a burr. The burr is then used to create a small cavity in the bone for the tendon to fit inside. Two small suture anchors are embedded into the cavity in the radial tuberosity. These anchors can either be screwed into the bone or implanted like a staple. Each anchor has a long thread (suture) connected to it. The suture is woven into the lower end of the tendon and crisscrossed upward. The surgeon slides the sutures back and forth, which coaxes the end of the tendon into the cavity. When the end of the tendon is positioned in the cavity, the surgeon tightens the sutures, fixing the tendon in place.

When the surgeon is satisfied with the repair, the skin incisions are closed, and the elbow is placed either in a cast or a range-of-motion brace.

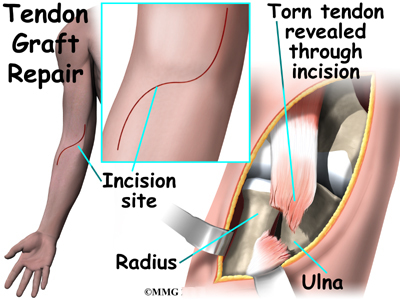

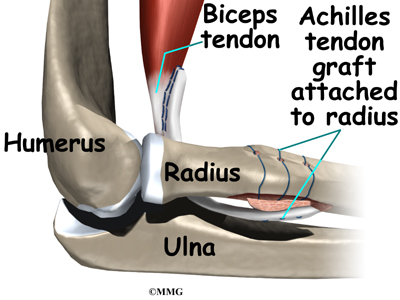

Graft Repair

If more than three or four weeks have passed since the rupture, the surgeon will usually need to make a larger incision in the front of the elbow. Also, because the tendon will have retracted further up the arm, graft tissue will be needed in order to reconnect the biceps to its original point of attachment on the radial tuberosity.

The surgeon begins by making a curved incision across the arm, just above the elbow joint. The incision curves along the front surface of the upper arm to expose the lower part of the biceps muscle. The surface of the radial tuberosity is removed. A burr is used to create a small cavity within the tuberosity. Several suture holes are drilled around the rim of the tuberosity.

A curved instrument is passed through the incision and directly between the radius and ulna bones. The surgeon pushes the instrument through this space, puncturing the muscles and soft tissues. The surgeon feels the back of the forearm to find the point where the instrument is protruding. A second incision is made at this spot.

The surgeon then prepares a graft of tissue to lengthen the retracted biceps tendon. Some surgeons use a piece of hamstring tendon for the graft. Others use a section of the Achilles tendon where it attaches to the heel. This type of graft is usually an allograft, meaning that the tissue is taken from a cadaver (human tissue preserved for medical purposes).

When the Achilles tendon allograft is used, the surgeon leaves a small piece of the heel bone attached to the piece of tendon. Small holes are drilled into the piece of bone. Sutures are woven through these holes and will later be used to secure the end of the graft to the radial tuberosity. In this way, the graft will have a bone-to-bone connection that heals together. The healed bone solidly fixes the the graft to the radial tuberosity. After the graft is in place, its top end is then stitched over the front of the biceps muscle.

Next, the lower end of the graft is passed between the radius and ulna, exiting through the second incision that was made on the back of the forearm. The sutures from the bony end of the graft are threaded into holes that were drilled into the rim of the radial tuberosity earlier. The surgeon ties the sutures, securing the graft to the radius.

When the surgeon is satisfied with the repair, the skin incisions are closed, and the elbow is placed in a protective brace.

Rehabilitation

How soon can I use my elbow again?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

When a ruptured biceps tendon is treated nonsurgically, you may need to avoid heavy arm activity for three to four weeks. As the pain and swelling resolve, it will become safe to begin doing more normal activities.

If the tendon is only partially torn, recovery takes longer. Patients usually need to rest the elbow using a protective splint or sling. As symptoms ease, you will usually begin a carefully progressed rehabilitation program under the supervision of a physical or occupational therapist. The program often involves one to two months of therapy.

After Surgery

Rehabilitation takes even longer after surgery. Immediately after surgery, your surgeon may cast your elbow for up to six weeks. Some surgeons prefer to use a special range-of-motion brace with careful elbow motion starting within one to two weeks. When you start therapy, your first few sessions may involve ice and electrical stimulation treatments to help control pain and swelling from the surgery. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

You will gradually start exercises to improvement movement in the forearm, elbow, and shoulder. You need to be careful to avoid doing too much, too quickly.

Exercises for the biceps muscle are avoided until at least four to six weeks after surgery. Your therapist may begin with light isometric strengthening exercises. These exercises work the biceps muscle without straining the healing tendon.

At about six weeks, you start doing more active strengthening. As you progress, your therapist will teach you exercises to strengthen and stabilize the muscles and joints of the wrist and hand, elbow, and shoulder. Other exercises will work your elbow in ways that are similar to your work tasks and sport activities. Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don’t put too much stress on your elbow.

You may require therapy for two to three months. It generally takes four to six months to safely begin doing forceful biceps activity. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

Elbow Anatomy

A Patient’s Guide to Elbow Anatomy

Introduction

At first, the elbow seems like a simple hinge. But when the complexity of the interaction of the elbow with the forearm and wrist is understood, it is easy to see why the elbow can cause problems when it does not function correctly. Part of what makes us human is the way we are able to use our hands. Effective use of our hands requires stable, painless elbow joints.

In addition to reading this article, be sure to watch our Elbow Anatomy Animated Tutorial Video.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts make up the elbow

- how those parts work together

Important Structures

The important structures of the elbow can be divided into several categories. These include

- bones and joints

- ligaments and tendons

- muscles

- nerves

- blood vessels

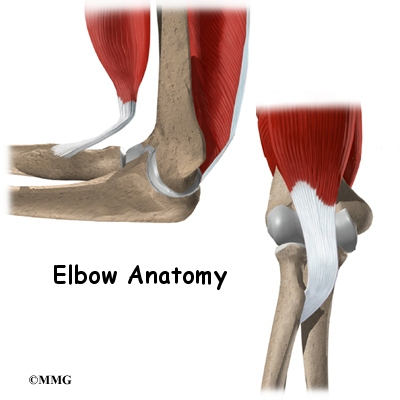

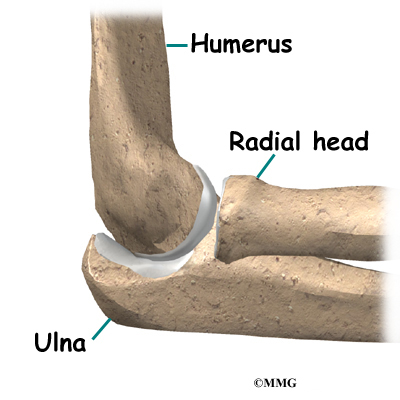

Bones and Joints

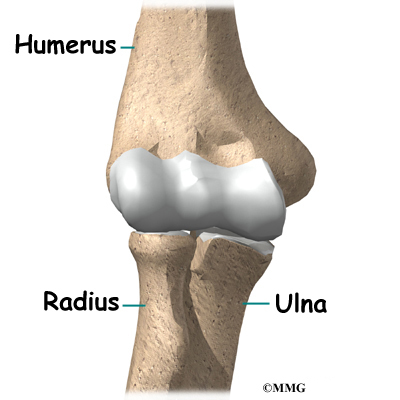

The bones of the elbow are the humerus (the upper arm bone), the ulna (the larger bone of the forearm, on the opposite side of the thumb), and the radius (the smaller bone of the forearm on the same side as the thumb). The elbow itself is essentially a hinge joint, meaning it bends and straightens like a hinge. But there is a second joint where the end of the radius (the radial head) meets the humerus. This joint is complicated because the radius has to rotate so that you can turn your hand palm up and palm down. At the same time, it has to slide against the end of the humerus as the elbow bends and straightens. The joint is even more complex because the radius has to slide against the ulna as it rotates the wrist as well. As a result, the end of the radius at the elbow is shaped like a smooth knob with a cup at the end to fit on the end of the humerus. The edges are also smooth where it glides against the ulna.

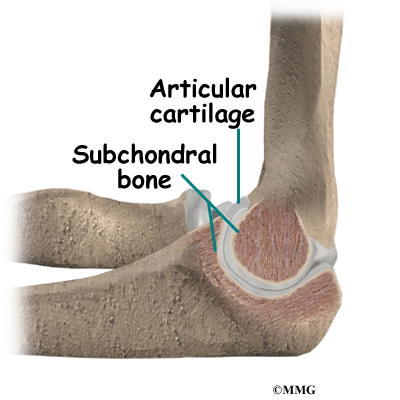

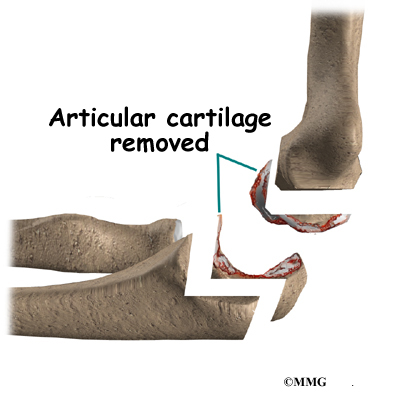

Articular cartilage is the material that covers the ends of the bones of any joint. Articular cartilage can be up to one-quarter of an inch thick in the large, weight-bearing joints. It is a bit thinner in joints such as the elbow, which don’t support weight. Articular cartilage is white, shiny, and has a rubbery consistency. It is slippery, which allows the joint surfaces to slide against one another without causing any damage.

The function of articular cartilage is to absorb shock and provide an extremely smooth surface to make motion easier. We have articular cartilage essentially everywhere that two bony surfaces move against one another, or articulate. In the elbow, articular cartilage covers the end of the humerus, the end of the radius, and the end of the ulna.

Ligaments and Tendons

There are several important ligaments in the elbow. Ligaments are soft tissue structures that connect bones to bones. The ligaments around a joint usually combine together to form a joint capsule. A joint capsule is a watertight sac that surrounds a joint and contains lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

In the elbow, two of the most important ligaments are the medial collateral ligament and the lateral collateral ligament. The medial collateral is on the inside edge of the elbow, and the lateral collateral is on the outside edge. Together these two ligaments connect the humerus to the ulna and keep it tightly in place as it slides through the groove at the end of the humerus. These ligaments are the main source of stability for the elbow. They can be torn when there is an injury or dislocation to the elbow. If they do not heal correctly the elbow can be too loose, or unstable.

There is also an important ligament called the annular ligament that wraps around the radial head and holds it tight against the ulna. The word annular means ring shaped, and the annular ligament forms a ring around the radial head as it holds it in place. This ligament can be torn when the entire elbow or just the radial head is dislocated.

There are several important tendons around the elbow. The biceps tendon attaches the large biceps muscle on the front of the arm to the radius. It allows the elbow to bend with force. You can feel this tendon crossing the front crease of the elbow when you tighten the biceps muscle. The triceps tendon connects the large triceps muscle on the back of the arm with the ulna. It allows the elbow to straighten with force, such as when you perform a push-up.

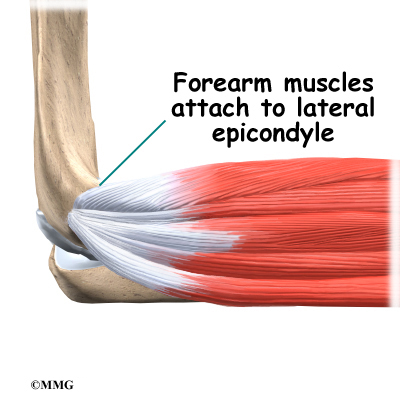

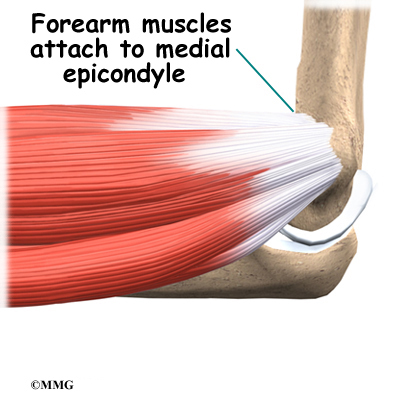

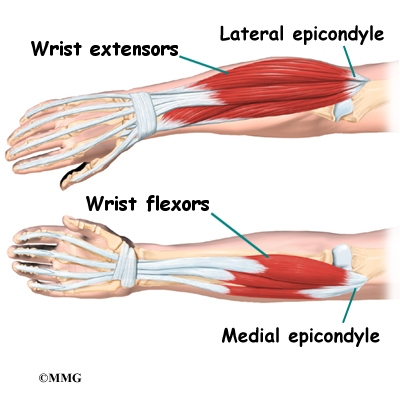

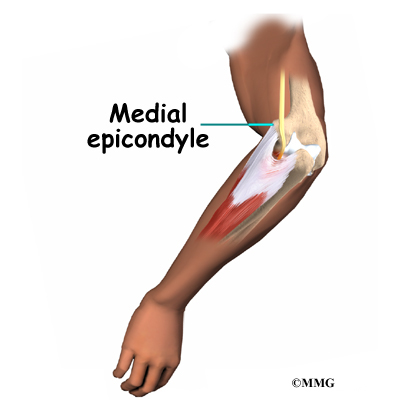

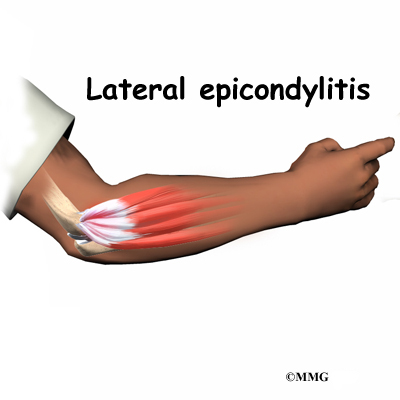

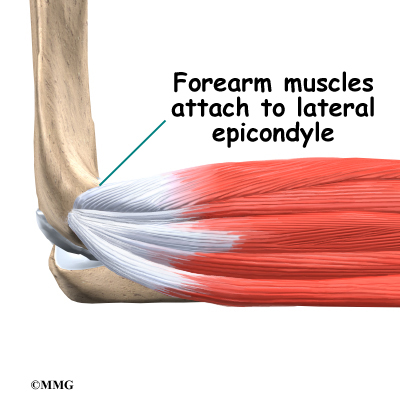

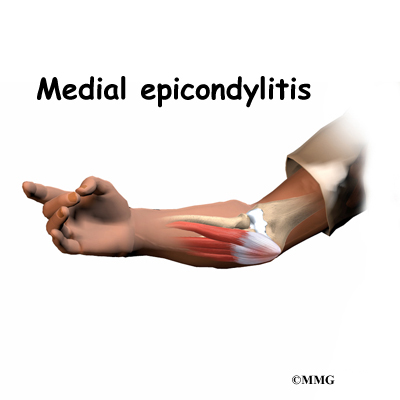

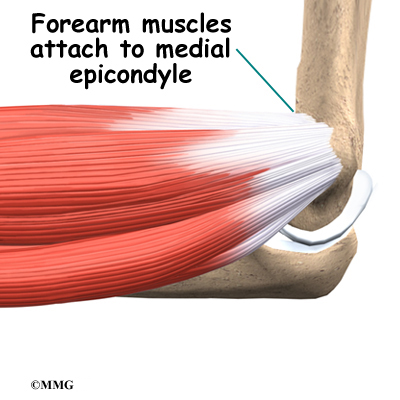

The muscles of the forearm cross the elbow and attach to the humerus. The outside, or lateral, bump just above the elbow is called the lateral epicondyle. Most of the muscles that straighten the fingers and wrist all come together in one tendon to attach in this area. The inside, or medial, bump just above the elbow is called the medial epicondyle. Most of the muscles that bend the fingers and wrist all come together in one tendon to attach in this area. These two tendons are important to understand because they are a common location of tendonitis.

Muscles

The main muscles that are important at the elbow have been mentioned above in the discussion about tendons. They are the biceps, the triceps, the wrist extensors (attaching to the lateral epicondyle) and the wrist flexors (attaching to the medial epicondyle).

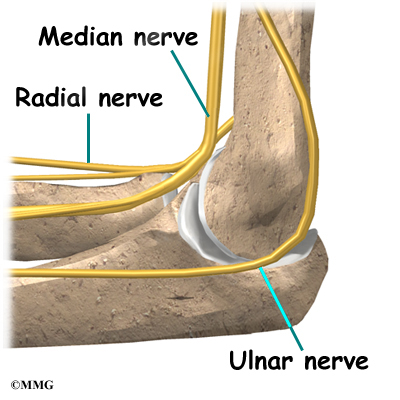

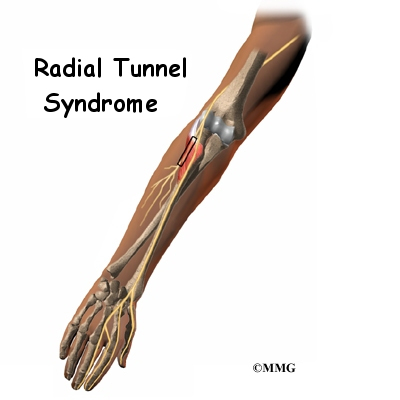

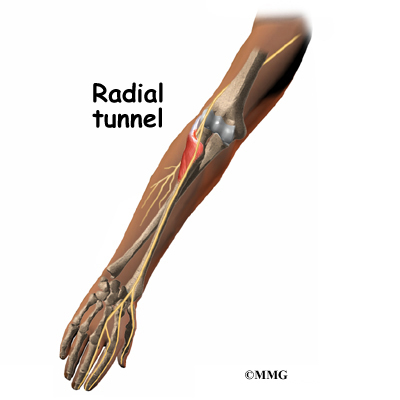

Nerves

All of the nerves that travel down the arm pass across the elbow. Three main nerves begin together at the shoulder: the radial nerve, the ulnar nerve, and the median nerve. These nerves carry signals from the brain to the muscles that move the arm. The nerves also carry signals back to the brain about sensations such as touch, pain, and temperature.

Some of the more common problems around the elbow are problems of the nerves. Each nerve travels through its own tunnel as it crosses the elbow. Because the elbow must bend a great deal, the nerves must bend as well. Constant bending and straightening can lead to irritation or pressure on the nerves within their tunnels and cause problems such as pain, numbness, and weakness in the arm and hand.

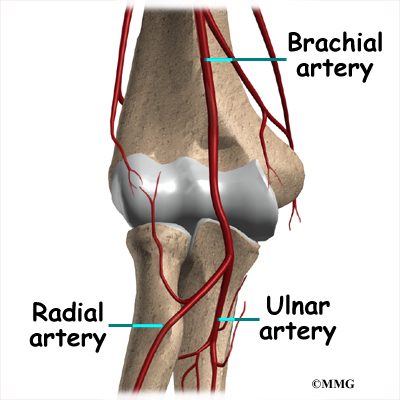

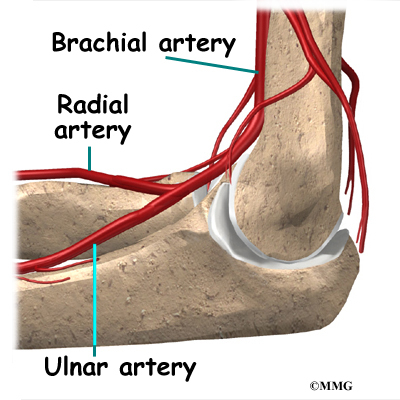

Blood Vessels

Traveling along with the nerves are the large vessels that supply the arm with blood. The largest artery is the brachial artery that travels across the front crease of the elbow. If you place your hand in the bend of your elbow, you may be able to feel the pulsing of this large artery. The brachial artery splits into two branches just below the elbow: the ulnar artery and the radial artery that continue into the hand. Damage to the brachial artery can be very serious because it is the only blood supply to the hand.

Summary

As you can see, the elbow is more than a simple hinge. It is designed to provide maximum stability as we position our forearm to use our hand. When you realize all the different ways we use our hands every day and all the different positions we put our hands in, it is easy to understand how hard daily life can be when the elbow doesn’t work well.

Elbow Replacement

A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Elbow

Introduction

Elbow joint replacement (also called elbow arthroplasty) can effectively treat the problems caused by arthritis of the elbow. The procedure is also becoming more widely used in aging adults to replace joints damaged by fractures. The artificial elbow is considered successful by more than 90 percent of patients who have elbow joint replacement.

This guide will help you understand

- how the elbow joint works

- what happens during surgery to replace the elbow joint

- what you can expect after elbow joint replacement

Anatomy

How does the elbow joint work?

The elbow joint is made up of three bones: the humerus bone of the upper arm, and the ulna and radius bones of the forearm.

The ulna and the humerus meet at the elbow and form a hinge. This hinge allows the arm to straighten and bend. The large triceps muscle in the back of the arm attaches to the point of the ulna (the olecranon). When this muscle contracts, it straightens out the elbow. The biceps muscles in the front of the arm contracts to bend the elbow.

Inside the elbow joint, the bones are covered with articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is a slick, smooth material. It protects the bone ends from friction when they rub together as the elbow moves. Articular cartilage is soft enough to act as a shock absorber. It is also tough enough to last a lifetime, if it is not injured.

The connection of the radius to the humerus allows rotation of the forearm. The upper end of the radius is round. This round end turns against the ulna and the humerus as the forearm and hand turn from palm down (pronation) to palm up supination).

Rationale

What makes elbow joint replacement surgery necessary?

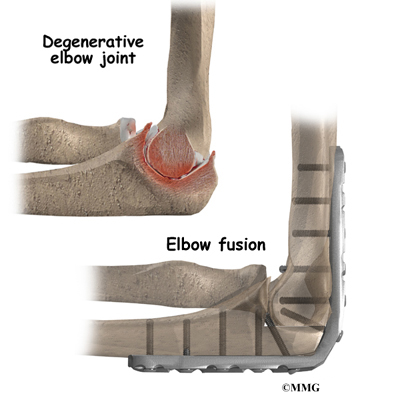

A joint replacement surgery is usually considered a last resort for a badly damaged and painful elbow joint. The artificial joint replaces the damaged surfaces with metal and plastic that are designed to fit together and rub smoothly against each other. This takes away the pain of bone rubbing against bone.

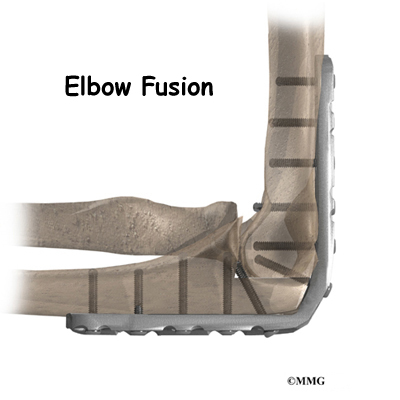

The most common reason for an artificial elbow replacement is arthritis. There are two main types of arthritis, degenerative and systemic. Degenerative arthritis is also called wear-and-tear arthritis, or osteoarthritis. Any injury to the elbow can damage the joint and lead to degenerative arthritis. Arthritis may not show up for many years after the injury.

There are many types of systemic arthritis. The most common form is rheumatoid arthritis. All types of systemic arthritis are diseases that affect many, or even all, of the joints in the body. Systemic arthritis causes destruction of the joints’ articular cartilage lining.

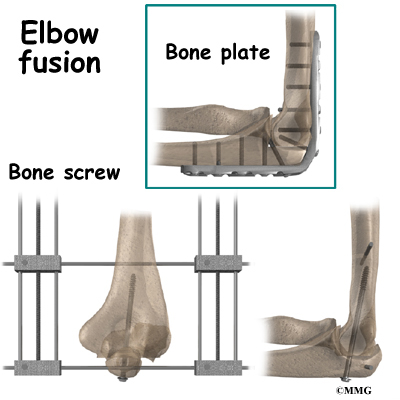

An elbow joint replacement may also be used immediately following certain types of elbow fractures, usually in aging adults. Elbow fractures are difficult to repair surgically in the best of circumstances. In many aging adults, the bone is also weak from osteoporosis. (People with osteoporosis have bones that are less dense than they should be.) The weakened bone makes it much harder for the surgeon to use metal plates and screws to hold the fractured pieces of bone in place long enough for them to heal together. In cases like this, it is sometimes better to remove the fractured pieces and replace the elbow with an artificial joint.

Preparation

What do I need to know before surgery?

You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

You may also need to spend time with the physical or occupational therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this pre-operative visit is to record a baseline of information. Your therapist will check your current pain levels, ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each elbow.

A second purpose of the pre-operative therapy visit is to prepare you for surgery. You’ll begin learning some of the exercises you’ll use during your recovery. And your therapist can help you anticipate any special needs or problems you might have at home, once you’re released from the hospital.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before. Come prepared to stay in the hospital for at least one night.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during an elbow replacement surgery?

Replacement surgery is usually not considered until it has become impossible to control your symptoms without surgery. If replacement becomes necessary, it can be a very effective way to take away the pain of arthritis and to regain use of your elbow.

Before we describe the procedure, let’s look first at the artificial elbow itself.

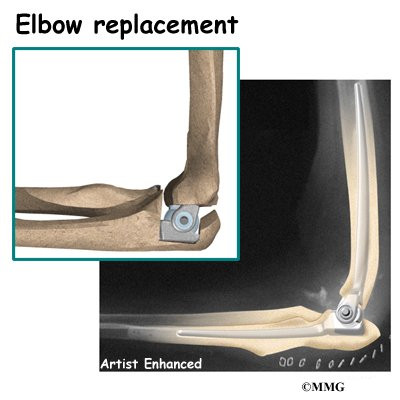

The Artificial Elbow

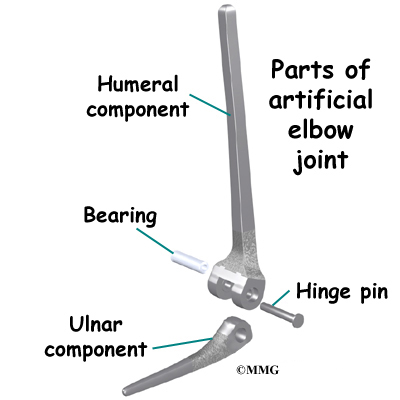

There is more than one kind of artificial elbow joint (also called a prosthesis). The most common types are like a hinge.

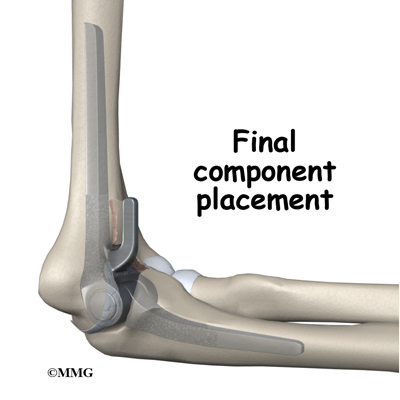

Each prosthesis has two parts. The humeral component replaces the lower end of the humerus in the upper arm. The humeral component has a long stem that anchors it into the hollow center of the humerus. The ulnar component replaces the upper end of the ulna in the lower arm. The ulnar component has a shorter metal stem that anchors it into the hollow center of the ulna.

The hinge between the two components is made of metal and plastic. The plastic part of the hinge is tough and slick. It allows the two pieces of the new joint to glide easily against each other as you move your elbow. The hinge allows the elbow to bend and straighten smoothly.

There are two different ways to hold the artificial elbow in place:

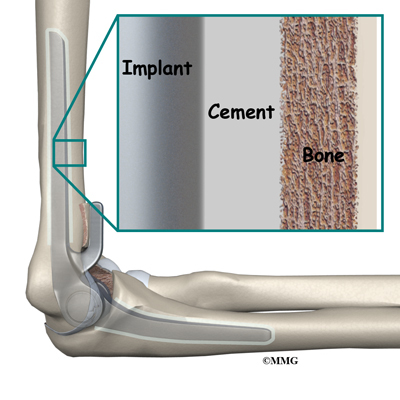

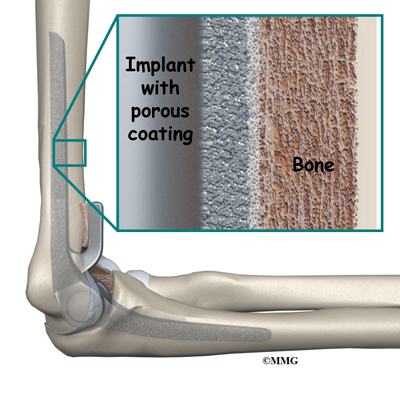

A cemented prosthesis uses a special type of epoxy cement to glue it to the bone.

An uncemented prosthesis has a fine mesh of holes on the surface. Over time, the bone grows into the mesh, anchoring the prosthesis to the bone.

The Operation

Most elbow replacement surgeries are done under general anesthesia. General anesthesia puts you to sleep. In some cases surgery is done with regional anesthesia, which deadens only the nerves of the arm. If you use regional anesthesia, you may also get medications to help you drift off to sleep, so you are not aware of the surgery.

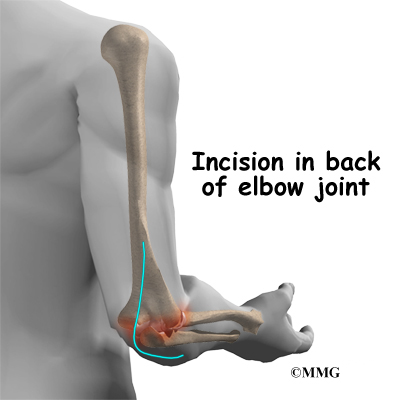

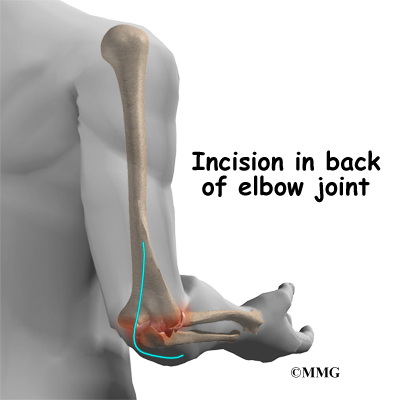

After the anesthesia, the surgeon makes an incision in the back of the elbow joint. The incision is made on the back side because most of the blood vessels and nerves are on the inside of the elbow. Entering from the back side helps prevent damage to them. The tendons and ligaments are then moved out of the way. Care must be taken to move the ulnar nerve, which runs along the elbow to the hand.

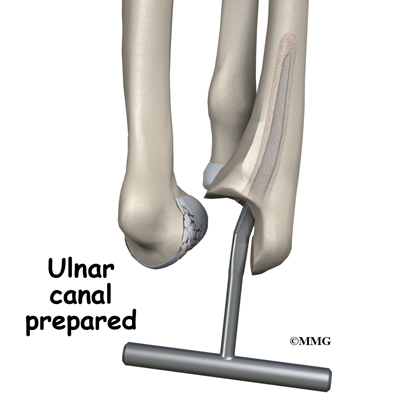

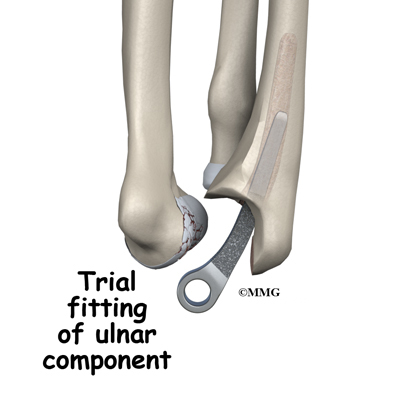

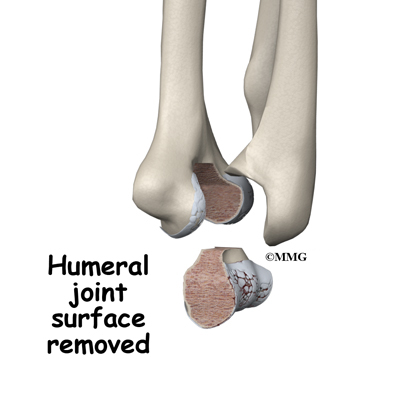

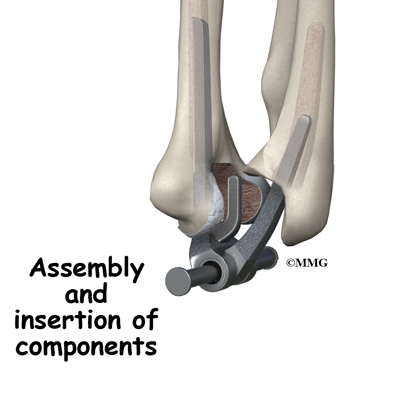

Once the joint is exposed, the first step is to remove the joint surfaces of the ulna and the radius. This is usually done with a surgical saw. The surgeon then uses a special rasp to hollow out the marrow space within the ulna to hold the metal stem of the ulnar component. The ulnar component is then to test the fit. If necessary, the surgeon will use the rasp to reshape the hole in the ulna.

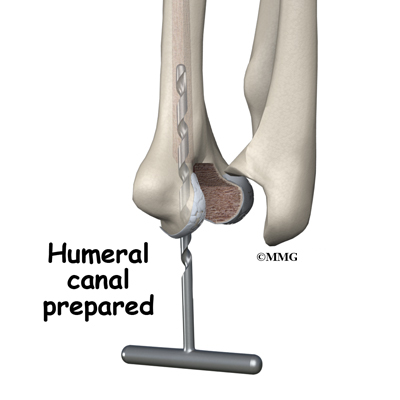

When the ulnar component has been fitted correctly, the surgeon repeats the procedure on the humerus.

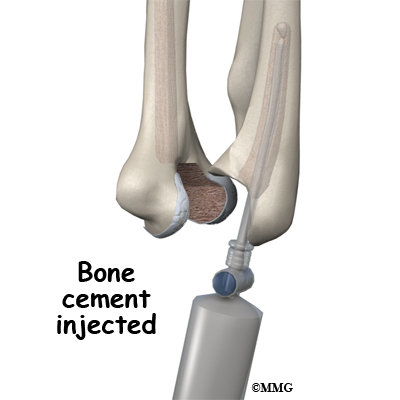

After the humeral component has been fitted, the surgeon puts together the pieces of the implant and checks to see if the hinge is working correctly. The implant is then removed, and the bone is prepared to cement it in place. The pieces are cemented in place and put together. After another check for proper fit and motion, the surgeon sews up the incision.

Your elbow will probably be placed in a bulky dressing and splint. You will then be awakened and taken to the recovery room.

Complications

Does elbow replacement surgery cause any problems?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This is not intended to be a complete list of complications. Some of the most common complications following elbow replacement are

- anesthesia

- infection

- loosening

- nerve or blood vessel injury

Anesthesia

Problems can arise when the anesthesia given during surgery causes a reaction with other drugs the patient is taking. In rare cases, a patient may have problems with the anesthesia itself. In addition, anesthesia can affect lung function because the lungs don’t expand as well while a person is under anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Infection

Infection following joint replacement surgery can be very serious. The chances of developing an infection after most artificial joint replacements are low, about one or two percent. Elbow replacement has a somewhat higher chance of infection, for many reasons. The skin is thin around the elbow, and no muscles cover the joint. This makes wound complications more common. Elbow replacements are also done more often in people who have rheumatoid arthritis. This disease and the drugs used to treat it affect the body’s immune system, making it harder to fight off infections.

Sometimes infections show up very early, before you leave the hospital. Other times infections may not show up for months, or even years, after the operation. Infection can also spread into the artificial joint from other infected areas. Once an infection lodges in your joint, it is almost impossible for your immune system to clear it. You may need to take antibiotics when you have dental work or surgical procedures on your bladder and colon. The antibiotics reduce the risk of spreading germs to the artificial joint.

Loosening

The major reason that artificial joints eventually fail is that they loosen where the metal or cement meets the bone. A loose joint implant can cause pain. If the pain becomes unbearable, another operation will probably be needed to fix the artificial joint.

There have been great advances in extending the life of artificial joints. However, most implants will eventually loosen and require another surgery. Younger, more active patients have a higher risk of loosening. In the case of an artificial knee joint, you could expect about 12 to 15 years, but artificial elbow joints tend to loosen sooner.

Nerve or Blood Vessel Injury

All of the large nerves and blood vessels to the forearm and hand travel across the elbow joint. Because surgery takes place so close to these nerves and vessels, it is possible to injure them during surgery. The result may be temporary if the nerves have been stretched by retractors holding them out of the way during the procedure. It is very uncommon to have permanent injury to either the nerves or the blood vessels, but it is possible.

After Surgery

What can I expect right after surgery?

After surgery, your elbow will probably be covered by a bulky bandage and a splint. Depending on the type of implant used, your elbow will either be positioned straight or slightly bent. You may also have a small plastic tube that drains blood from the joint. Draining prevents excessive swelling from the blood. (This swelling is sometimes called a hematoma.) The draining tube will probably be removed within the first day. Assisted elbow movements are started by an occupational or physical therapist the day after surgery.

Your surgeon will want to check your elbow within five to seven days. Stitches will be removed after 10 to 14 days, though most of your stitches will be absorbed into your body. You may have some discomfort after surgery. You will be given pain medicine to control the discomfort you have.

You should keep your elbow elevated above the level of your heart for several days to avoid swelling and throbbing. Keep it propped up on a stack of pillows when sleeping or sitting.

Rehabilitation

How soon will I be able to use my elbow again?

A physical or occupational therapist will direct your rehabilitation program. Recovery takes up to three months after elbow replacement surgery. The first few therapy treatments will focus on controlling the pain and swelling from surgery. Heat treatments may be used. Your therapist may also use gentle massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain.

Then you’ll begin gentle range-of-motion exercises. Strengthening exercises are used to give added stability around the elbow joint. You’ll learn ways to lift and carry items in order to do your tasks safely and with the least amount of stress on your elbow joint. As with any surgery, you need to avoid doing too much, too quickly.

Some of the exercises you’ll do are designed get your elbow working in ways that are similar to your work tasks and daily activities. Your therapist will help you find ways to do your tasks that don’t put too much stress on your new elbow joint. Before your therapy sessions end, your therapist will teach you a number of ways to avoid future problems.

Your therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control, improve your strength and range of motion, and maximize the use of your elbow. When you are well under way, regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource for you, but you will be in charge of doing exercises as part of an ongoing home program.

Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

A Patient’s Guide to Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

Introduction

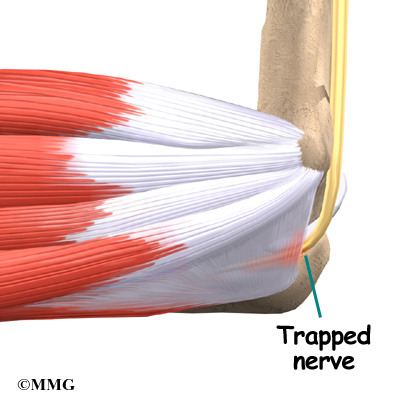

Cubital tunnel syndrome is a condition that affects the ulnar nerve where it crosses the inside edge of the elbow. The symptoms are very similar to the pain that comes from hitting your funny bone. When you hit your funny bone, you are actually hitting the ulnar nerve on the inside of the elbow. There, the nerve runs through a passage called the cubital tunnel. When this area becomes irritated from injury or pressure, it can lead to cubital tunnel syndrome.

This guide will help you understand

- what causes this condition

- ways to make the pain go away

- what you can do to prevent future problems

Anatomy

What is the cubital tunnel?

The ulnar nerve actually starts at the side of the neck, where the individual nerve roots leave the spine. The nerve roots exit through small openings between the vertebrae. These openings are called neural foramina.

The nerve roots join together to form three main nerves that travel down the arm to the hand. One of these nerves is the ulnar nerve.

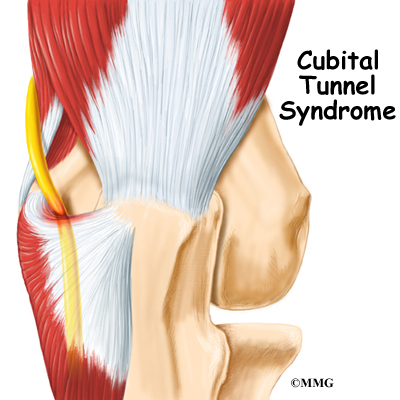

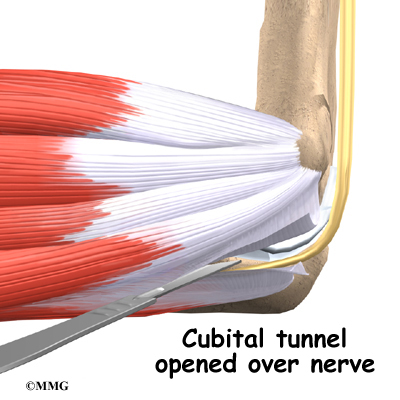

The ulnar nerve passes through the cubital tunnel just behind the inside edge of the elbow. The tunnel is formed by muscle, ligament, and bone. You may be able to feel it if you straighten your arm out and rub the groove on the inside edge of your elbow.

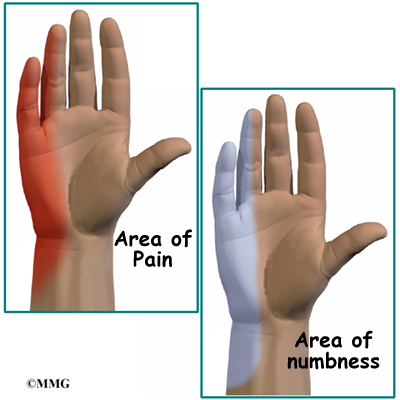

The ulnar nerve passes through the cubital tunnel and winds its way down the forearm and into the hand. It supplies feeling to the little finger and half the ring finger. It works the muscle that pulls the thumb into the palm of the hand, and it controls the small muscles (intrinsics) of the hand.

Causes

What causes cubital tunnel syndrome?

Cubital tunnel syndrome has several possible causes. Part of the problem may lie in the way the elbow works. The ulnar nerve actually stretches several millimeters when the elbow is bent. Sometimes the nerve will shift or even snap over the bony medial epicondyle. (The medial epicondyle is the bony point on the inside edge of the elbow.) Over time, this can cause irritation.

One common cause of problems is frequent bending of the elbow, such as pulling levers, reaching, or lifting. Constant direct pressure on the elbow over time may also lead to cubital tunnel syndrome. The nerve can be irritated from leaning on the elbow while you sit at a desk or from using the elbow rest during a long drive or while running machinery. The ulnar nerve can also be damaged from a blow to the cubital tunnel.

Symptoms

What does cubital tunnel syndrome feel like?

Numbness on the inside of the hand and in the ring and little fingers is an early sign of cubital tunnel syndrome. The numbness may develop into pain. The numbness is often felt when the elbows are bent for long periods, such as when talking on the phone or while sleeping. The hand and thumb may also become clumsy as the muscles become affected.

Tapping or bumping the nerve in the cubital tunnel will cause an electric shock sensation down to the little finger. This is called Tinel’s sign.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Medial Epicondylitis

Diagnosis

How will my doctor know I have cubital tunnel syndrome?

Your doctor will take a detailed medical history. You will be asked questions about which fingers are affected and whether or not your hand is weak. You will also be asked about your work and home activities and any past injuries to your elbow.

Your doctor will then do a physical exam. The cubital tunnel is only one of several spots where the ulnar nerve can get pinched. Your doctor will try to find the exact spot that is causing your symptoms. The prodding may hurt, but it is very important to pinpoint the area causing you trouble.

You may need to do special tests to get more information about the nerve. One common test is the nerve conduction velocity (NCV) test. The NCV test measures the speed of the impulses traveling along the nerve. Impulses are slowed when the nerve is compressed or constricted.

The NCV test is sometimes combined with an electromyogram (EMG). The EMG tests the muscles of the forearm that are controlled by the ulnar nerve to see whether the muscles are working properly. If they aren’t, it may be because the nerve is not working well.

Treatment

How can I make my pain go away?

Nonsurgical Treatment