A Patient’s Guide to Adolescent Osteochondritis Dissecans of the Elbow

Introduction

Young gymnasts and overhand athletes, particularly baseball pitchers and racket-sport players, are prone to an odd and troubling elbow condition. The forceful and repeated actions of these sports can strain the immature surface of the outer part of the elbow joint. The bone under the joint surface weakens and becomes injured, which damages the blood vessels going to the bone. Without blood flow, the small section of bone dies. The injured bone cracks. It may actually break off. This condition is called osteochondritis dissecans (OCD).

In the past, this condition was called Little Leaguer’s elbow. It got its name because it was so common in baseball pitchers between the ages of 12 and 20. Now it is known that other sports, primarily gymnastics and racket sports, put similar forces on the elbow. These sports can also lead to elbow OCD in adolescent athletes.

This guide will help you understand

- how this problem develops

- how doctors identify the problem

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What part of the elbow does this problem affect?

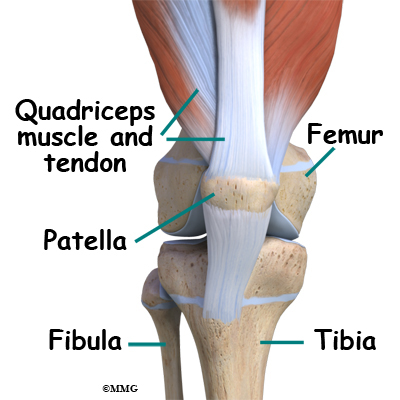

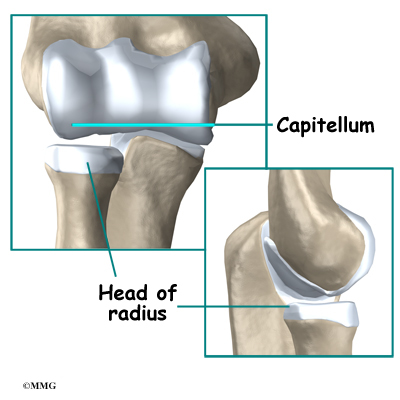

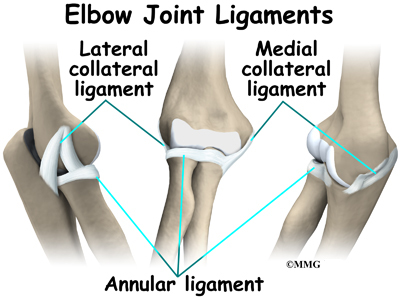

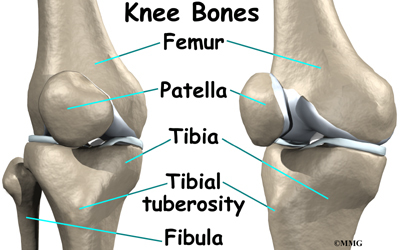

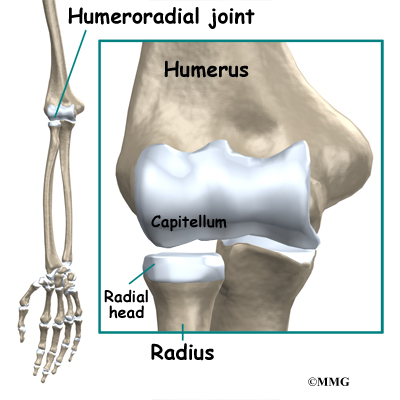

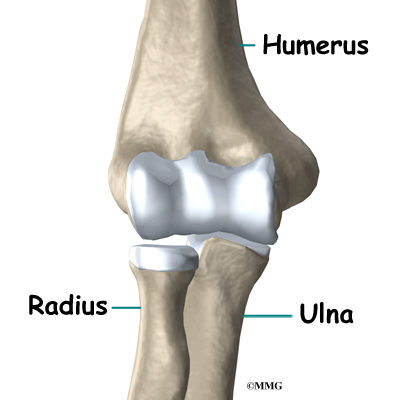

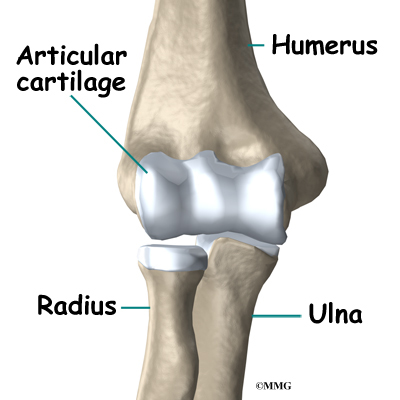

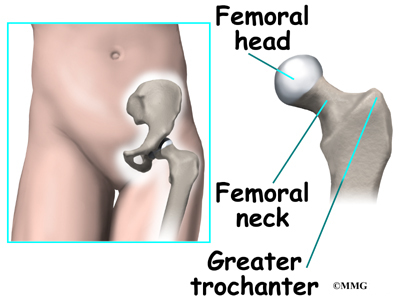

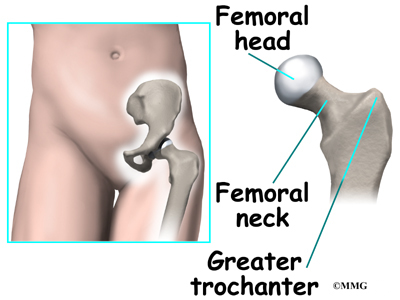

The elbow is the connection of the upper arm bone (the humerus) and the two bones of the forearm (the ulna and the radius). The radius runs from the outer edge of the elbow down the forearm to the thumb-side of the wrist.

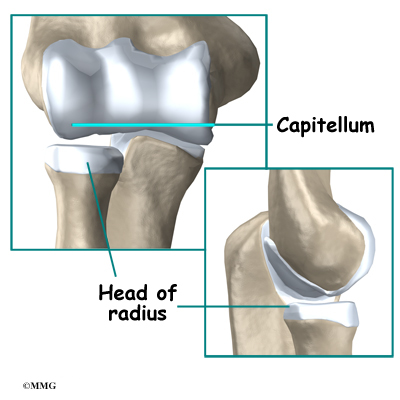

The joint where the humerus meets the radius is called the humeroradial joint. This joint is formed by a knob and a shallow cup. The knob on the end of the humerus is called the capitellum. The capitellum fits into the cup-shaped end of the radius. This cup is called the head of the radius.

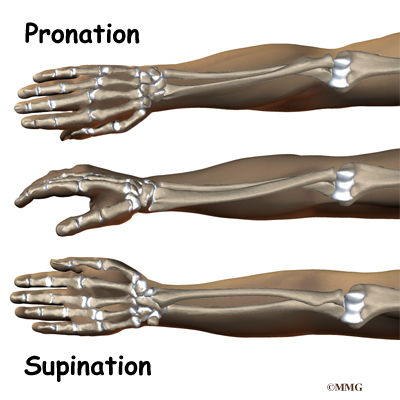

When the head of the radius spins on the capitellum, the forearm rotates so that the palm faces up toward the ceiling (supination) or down toward the floor (pronation). The joint also hinges as the elbow bends and straightens.

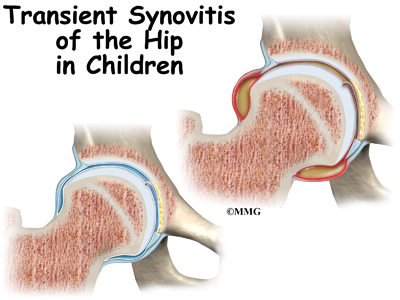

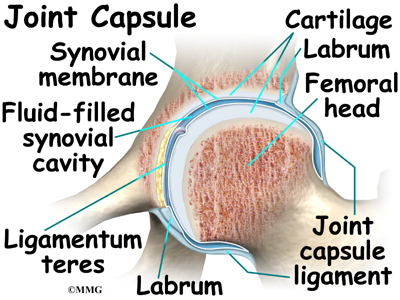

In the elbow joint, the ends of the bones are covered with articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is a slick, smooth material. It protects the bone ends from friction when they rub together as the elbow moves. Articular cartilage is soft enough to act as a shock absorber. It is also tough enough to last a lifetime, if it is not injured.

Elbow OCD affects the articular cartilage in the capitellum. It also affects the layer of bone just below the cartilage, which is called the subchondral bone. In advanced stages of OCD, the upper end of the radius, particularly the head of the radius, is also involved.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Elbow Anatomy

Causes

How does this problem develop?

The cause of elbow OCD in adolescents is unknown. Scientists think that genetics is one possibility. This means that certain families are more likely to develop OCD. The condition often occurs among relatives, and it is sometimes seen in several generations of the same family.

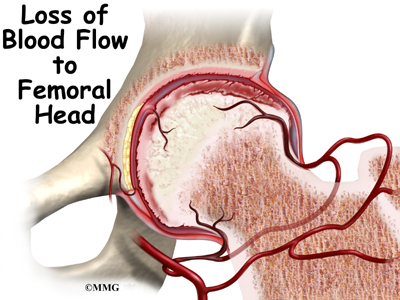

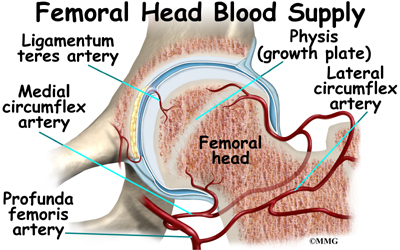

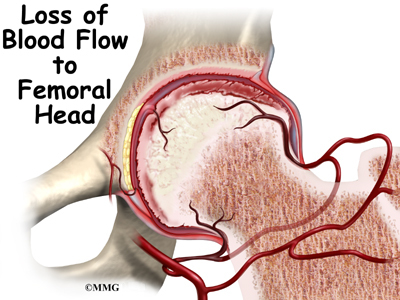

Another possible cause is that the tiny blood supply to the humeroradial joint is somehow blocked. Only the ends of a few small blood vessels enter the back of the humeroradial joint. If this scarce blood supply is damaged, there is no back-up.

Although the exact cause of elbow OCD in adolescents is not known, most experts agree that overuse of the elbow plays a major role in its development.

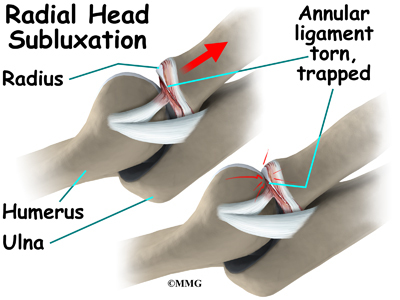

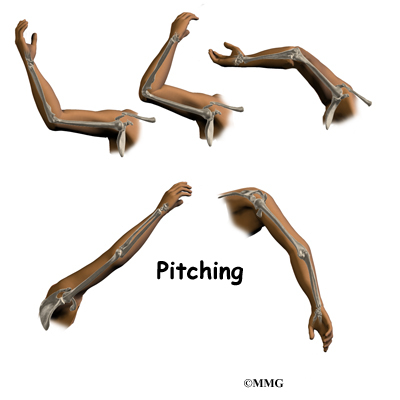

Pitching can lead to overuse strain and, in turn, elbow OCD. Throwing puts a lot of force on the elbow joint. When the throwing action is repeated over and over again, it can damage the immature joint surface of an adolescent’s elbow. After winding up and cocking the arm back, the pitcher must quickly accelerate the arm to gain ball speed. Then, almost immediately, the pitcher has to slow the arm down and follow through. The pitcher may angle the elbow outward slightly during the acceleration phase to get more ball speed. This action jams the head of the radius against the capitellum. During the slowing and follow-through after a pitch, the forearm is fully pronated. This action puts extra pressure on the humeroradial joint.

Hitting a ball with a racket can strain the elbow just like pitching a baseball. The player may angle the racket and elbow out slightly to gain ball speed. Hitting the ball with the arm and racket in this position jams the radial head against the capitellum, similar to what can happen during pitching motions. Gymnasts are also at risk for high forces on the capitellum when they repeatedly do maneuvers on their hands with their elbows locked out straight.

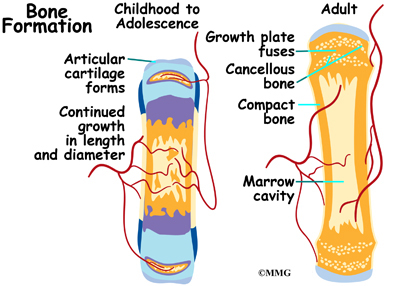

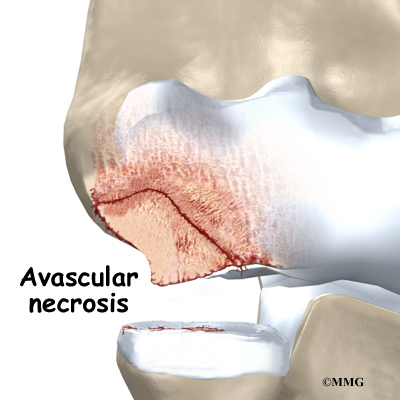

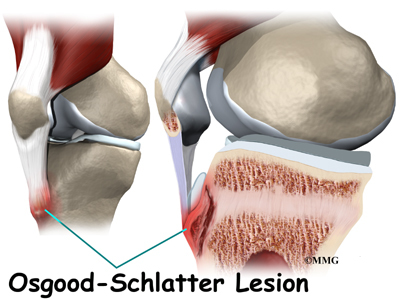

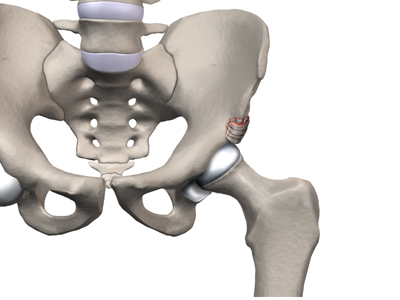

These actions done over and over again can eventually cause an overuse injury to the humeroradial joint of adolescent athletes. Adolescents’ articular cartilage is newly formed and so can’t handle these types of forces. The subchondral bone (under the articular cartilage) in the capitellum takes the brunt of the stress. A portion of the bone may eventually weaken, and possibly even crack. When the bone is damaged, the tiny blood supply going to the area is somehow blocked. Without blood supply, the small area of bone dies. This type of cell death is called avascular necrosis. (Avascular means without blood, and necrosis means death.)

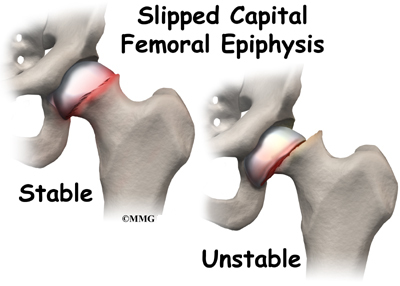

The crack may begin to separate. Eventually, the small piece of dead bone may break loose. This produces a separation between the articular cartilage and the subchondral bone, which is the condition called OCD. If the dead piece of bone comes completely detached, it becomes a loose body. The loose body is free to float around inside the joint.

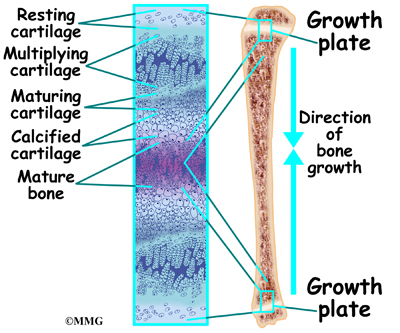

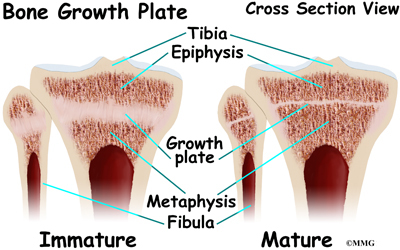

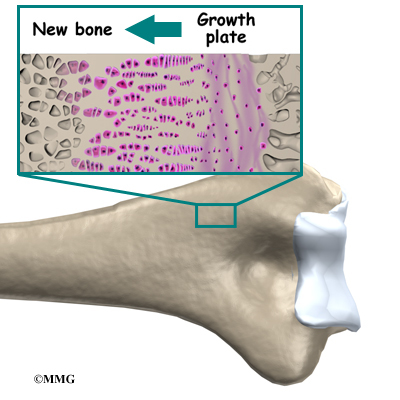

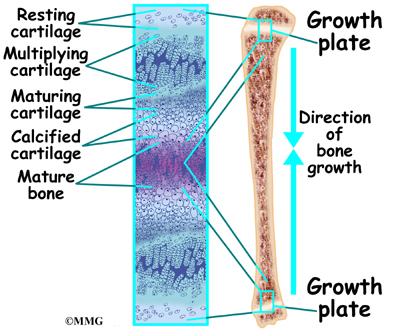

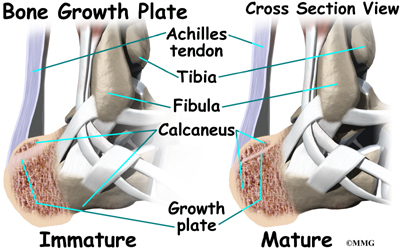

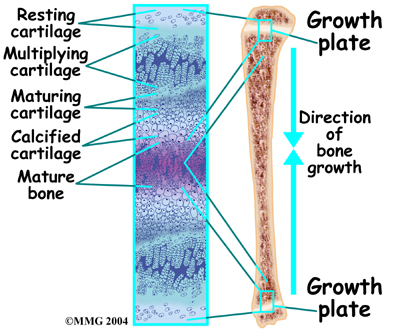

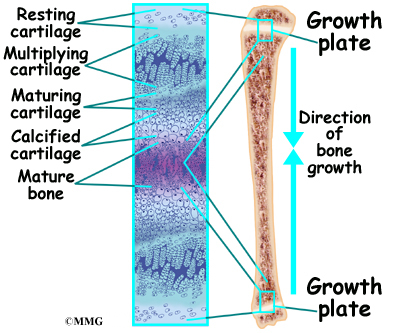

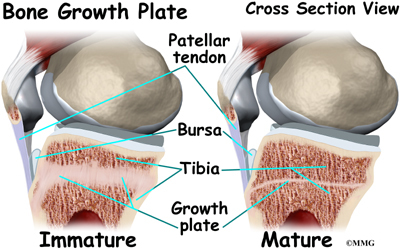

Another condition, called Panner’s disease, also affects the capitellum in children. It is not the same as elbow OCD in adolescents. Panner’s disease affects the bone growth center (the growth plate) of the capitellum. Panner’s disease generally occurs in kids (mainly boys) between five and 10. Panner’s disease is a childhood condition that involves the entire capitellum and usually heals completely when bone growth is complete.

Elbow OCD in adolescents is different. It occurs after growth in the capitellum has stopped, which is usually between the ages of 12 and 15. Elbow OCD in adolescents affects only a portion of the capitellum, generally along the inside and lower edges of the bony knob. Unless elbow OCD is diagnosed and treated early, the results are not as good as the results for Panner’s disease. The adolescent with elbow OCD sometimes ends up with elbow arthritis by early adulthood.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Panner’s Disease of the Elbow

Symptoms

What does this problem feel like?

Only about 20 percent of kids with elbow OCD remember hurting their elbow. The remainder usually develop symptoms over time, which is typical with overuse problems.

In the absence of a specific injury, the athlete may at first feel bothersome elbow discomfort only while playing sports. The soreness generally goes away quickly when the elbow is rested. Over time, however, the elbow pain worsens, is hard to pinpoint, and may linger after using the arm. The elbow feel may feel stiff, and it may not completely straighten out.

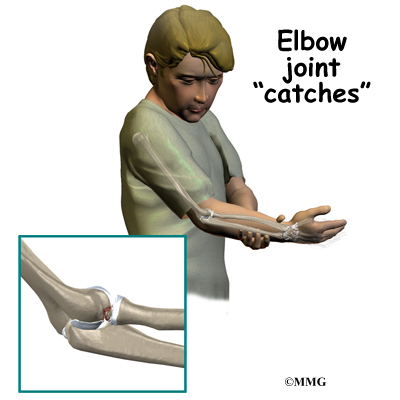

In advanced cases of elbow OCD, the patient may notice that the joint grinds (called crepitus). The elbow may catch, or even lock up occasionally. These sensations may mean that a loose body is floating around inside the elbow joint. The joint may also feel warm and swollen, and the muscles around the elbow may appear to have shrunk (atrophied).

Bad cases of elbow OCD, and those that are not caught and treated early, tend to create bigger problems later in life. The joint may become arthritic early in adulthood. As a result, the patient may always have greater difficulty using the problem elbow.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Osteoarthritis of the Elbow

Diagnosis

How do doctors identify the problem?

The doctor begins by asking questions about the patient’s age and sports participation. In the physical exam, the sore elbow and healthy elbow will be compared. The doctor checks for tenderness by pressing on and around the elbow. The amount of movement in each elbow is measured. The doctor checks for pain and crepitus when the forearm is rotated and when the elbow is bent and straightened.

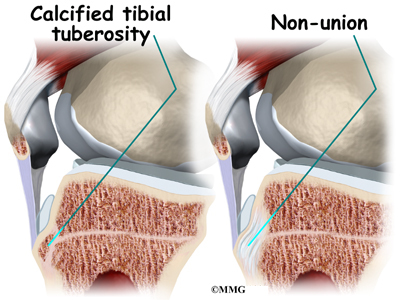

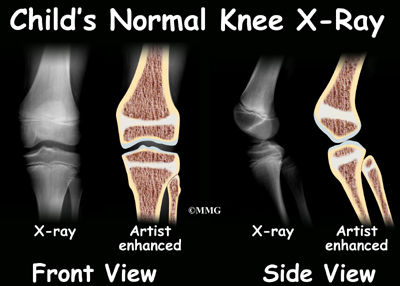

X-rays are needed to confirm the diagnosis. A front and a side view of the elbow are generally the most helpful. Early in the course of the problem, the X-rays may appear normal.

As the condition worsens, the X-ray image may show changes in the capitellum. The normal shape of the bony knob may appear irregular. In bad cases of elbow OCD, the capitellum might even look like it has flattened out, suggesting that the bone has collapsed. The X-ray could show a crack in the capitellum or even a loose body. In the late stages of elbow OCD, the radial head may appear enlarged, and the humeroradial joint not be aligned as it normally should. These findings suggest early arthritis.

A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may show more detail. The MRI can give an idea of the size of the affected area. It can show bone irregularities and also help detect swelling. Doctors may repeat the MRI test at various times to see if the area is healing.

The doctor might order a computed tomography (CT) scan. The CT scan helps confirm the diagnosis. A CT scan clearly shows bone tissue. The doctor can compare CT scans over a period of time to monitor changes in the bones of the elbow.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Nonsurgical Treatment

At first, athletes may need to stop their usual sport activities. This gives the elbow a rest so that healing can begin.

The doctor may prescribe anti-inflammatory medicine to help reduce pain and swelling. Patients are shown how to apply ice to the area. When sport activities are resumed, ice treatments should be used after activity. Ice treatments are simple to do. Place a wet towel on the elbow. Then lay an ice pack or bag of ice over the elbow for 10 to 15 minutes.

The doctor may also suggest working with a physical therapist. Physical therapists might use ice, heat, or ultrasound to control inflammation and pain. As symptoms ease, the physical therapist works on flexibility, strength, and muscle balance in the elbow.

Therapists also work with athletes to help them improve their form in ways that reduce strain on the elbow during sports. Pitchers and racket-sport players might benefit from keeping the elbow aligned correctly, instead of angled outward, during the acceleration phase of the pitch or swing.

When symptoms are especially bad, athletes may need to make changes that require less overhand activity. For example, pitchers could shift to playing first base. Gymnasts could focus on maneuvers that don’t stress the sore elbow. However, if the piece of bone is loose but still attached, all sports activities must be stopped. Sports can begin again when the patient has no pain and shows full elbow movement.

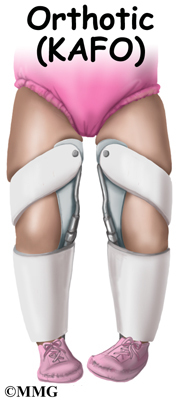

In severe cases, patients may need to wear a sling or a long-arm splint for several weeks before starting elbow motion exercises. As symptoms ease and elbow movement improves, a guided program of strengthening and sport training begins.

Surgery

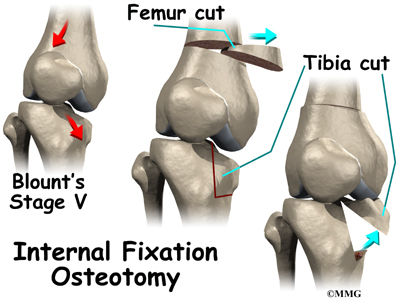

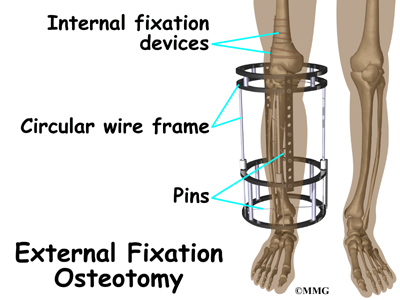

Patients may need surgery if the elbow locks up, if it won’t straighten out, or if pain continues even after a period of rest and physical therapy. Unfortunately, surgery isn’t 100 percent successful. The various procedures don’t necessarily improve athletes’ chances for returning to high-level competition. Patients often lose the ability to fully straighten the elbow. And even after surgery, they are prone to elbow arthritis in early adulthood.

Surgical procedures to treat elbow OCD are done from the outside edge of the elbow. The joint may be opened up to allow the surgeon to see and work on the joint. Opening up the joint is called arthrotomy. Many surgeons prefer instead to use an arthroscope. An arthroscope is a slender instrument with a TV camera on the end. The arthroscope can be inserted into a very small incision. It lets the surgeon see the area where he or she is working on a TV screen.

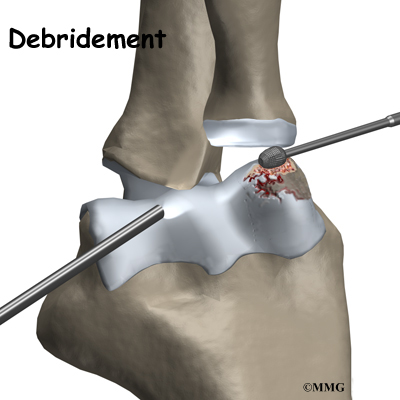

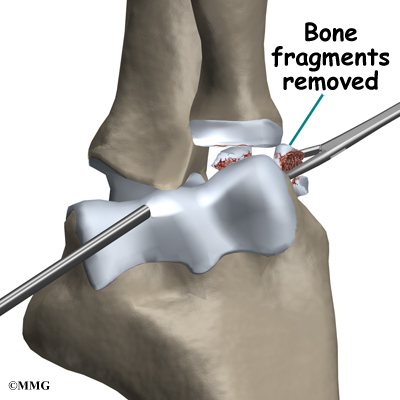

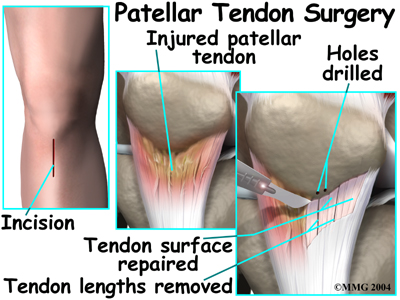

Debridement

Debridement is the most common procedure used for elbow OCD. It is especially helpful when the damaged part of the capitellum is loose but still attached. The surgeon uses a small shaver to clear away (debride) irritated tissue from the area. All the dead tissue is shaved away until the bone bleeds.

This allows the defect to fill with scar tissue. Often, surgeons use a small instrument to poke holes through the damaged area and into the healthy bone just below. Bleeding from the holes promotes healing. The surgeon looks for and removes any loose fragments of bone.

Pinning

If the section of bone has completely detached from the capitellum, the surgeon may surgically pin the bone back in place. The spot where the bone detached is prepared. As in debridement, the bone tissue is shaved until it bleeds. Then the surgeon attempts to replace the loose piece of bone exactly in its original position. Small lengths of surgical wire are inserted through the bone fragment and into the main bone. The wires hold the piece of bone in place so that it can heal. The wires are usually left in place and not removed at a later date.

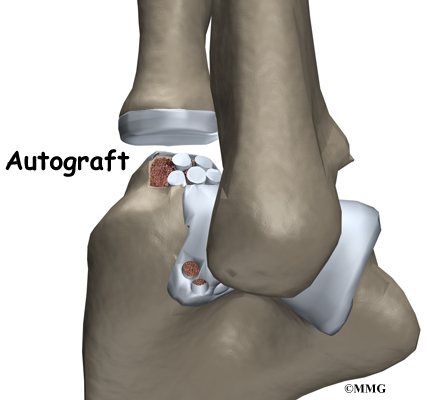

Graft Method

Damage to a small area of the capitellum may be replaced with a graft (replacement tissue). The idea is to fill in the spot in order to reshape the knob of the capitellum. By using a piece of living tissue for the graft, it is hoped that the graft will restore the normal function of the original articular cartilage. The results of this procedure are not always optimal. The goal is that, by reshaping the capitellum, the alignment of the humeroradial joint will be improved. When it works, the joint has a better chance of lasting longer before becoming arthritic.

This procedure uses an autograft, a graft of tissue from the patient’s own body. The surgeon takes a small piece of bone and cartilage from a nearby area and puts it in the damaged area on the capitellum. The biggest challenge is getting the surface of the graft to match the original shape of the capitellum.

Rehabilitation

What can be expected from treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

In nonsurgical rehabilitation, the goal is to calm pain and inflammation and to protect the elbow from further harm. The doctor may prescribe anti-inflammatory medicine to help reduce pain and swelling.

The elbow may need to be rested. When symptoms are especially bad, patients may need to avoid activities that make their pain worse, including sports. Even after symptoms ease up, activity may need to be restricted for another six to eight weeks.

Some doctors have their patients work with a physical therapist. Treatments such as heat, ice, and ultrasound may be used to ease pain and swelling. Therapists also work with young athletes to help them improve their form and reduce strain on the elbow during sports.

When the elbow starts to feel better, exercises are begun to get the elbow moving. At first, the movements are done passively, meaning that the therapist moves the arm. This is followed with active motion exercise, which means the patient’s muscles help do the work of moving the arm. As elbow motion and strength improve, patients progress in more advanced strengthening exercises.

After Surgery

A bandage or dressing is worn for a week following the procedure. The stitches are generally removed in 10 to 14 days. However, if the surgeon used sutures that dissolve, patients don’t need to have the stitches taken out.

Patients are shown ways to protect the elbow after surgery. Although elbow motions are avoided early on, patients are shown ways to keep motion in their shoulder, wrist, and hand.

The surgeon may have the patient take part in formal physical therapy a few weeks after surgery. The first few physical therapy treatments are designed to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery.

Exercises are chosen to help improve elbow motion and to get the muscles toned and active again. At first, the elbow is exercised in positions and movements that don’t strain the healing cartilage. As the program evolves, more challenging exercises are chosen to safely advance the elbow’s strength and function.

Most patients will need to modify their activities after surgery. Most pitchers are unable to throw hard and without pain afterward. In general, most athletes with elbow OCD need to stop playing high-level sports due to lingering elbow pain and reduced elbow motion.

If symptoms come back again, patients must modify their activities until symptoms subside. They’ll need to avoid heavy sports activity until symptoms go away and they are able to safely begin exercising the elbow again.