A Patient’s Guide to Rehabilitation for Arthritis

Introduction

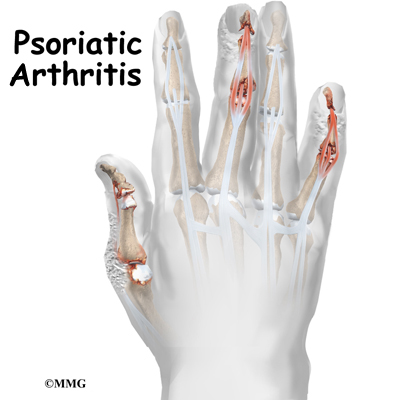

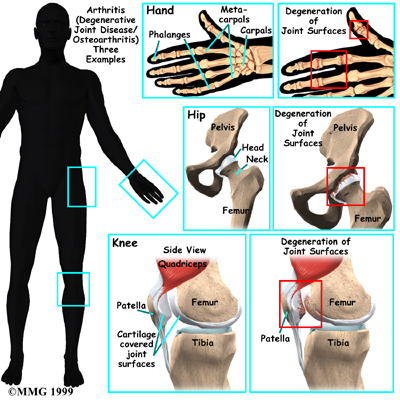

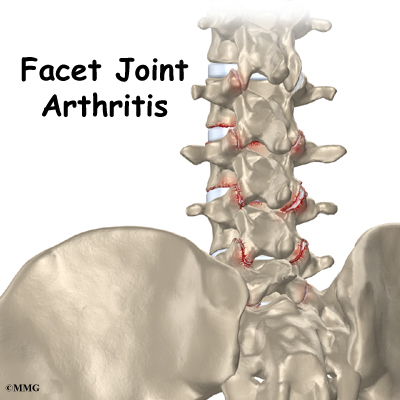

Arthritis is the most common cause of chronic disability. There is no cure for most forms of arthritis. But with some effort, you don’t need to lose all the movement in your joints. A rehabilitation program can help you maintain and even improve your joints’ strength and mobility. With some help from specialists and special equipment, arthritis won’t always stop you from doing the things you enjoy or the things you need to do.

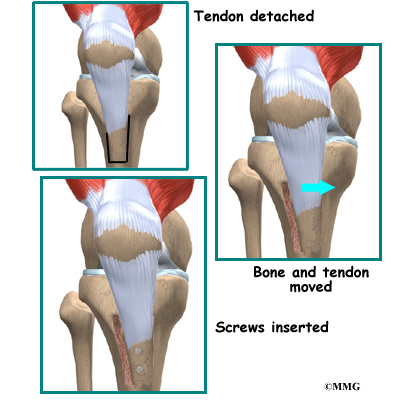

Rehabilitation is a hands-on form of care and relies on your participation and effort. It involves exercising, learning how to care for sore and swollen joints, and figuring out ways to minimize the stress on your joints. In the early stages of arthritis, the goal of rehabilitation is to maintain or improve your joint strength and range of motion. If your joint is severely damaged, rehabilitation will focus on managing your pain and finding special equipment to help you with necessary tasks. Rehabilitation also helps people recover from joint surgery. Your rehab program will involve managing your symptoms, exercise, and lifestyle changes.

Rehabilitation requires patience. It takes time to strengthen your joints and learn how to do familiar tasks in new ways. But the result can be a greatly improved quality of life.

Most doctors refer their patients to physical or occupational therapists for rehabilitation. Many other types of medical professionals are involved in caring for people with arthritis; rehabilitation nurses, vocational rehab counselors, recreational therapists, and sometimes even medical social workers, speech therapists, and psychologists. No matter what kinds of specialists you see, rehabilitation is a team effort–you, your doctor, and your therapists.

Your First Visit

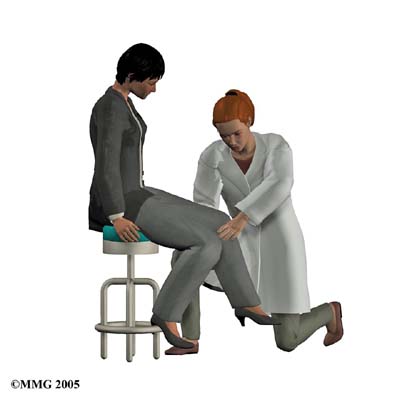

What happens on the first visit to the therapist’s office?

The first step in your rehabilitation is for your therapist to learn more about you and your joint problems.

History of the Problem

Your therapist will ask questions about your disease history, your day-to-day activities, and what you have problems doing. You may be asked to rate your pain on a scale from one to ten. Your answers will help guide your therapist’s examination. Below are some other questions your therapist may ask you.

- What makes your pain or symptoms better, and what makes them worse?

- How do your symptoms affect your daily activities?

- What treatments have been helpful for you?

Physical Examination

After reviewing your answers, your therapist will do an examination that may include some or all of the following checks.

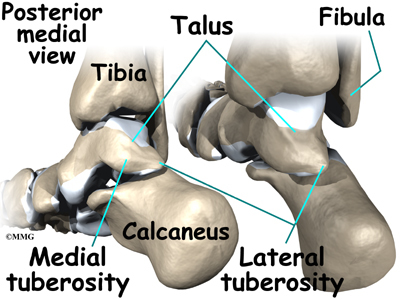

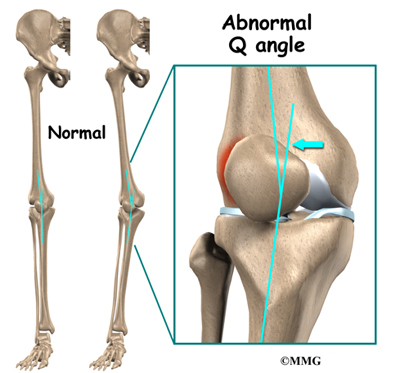

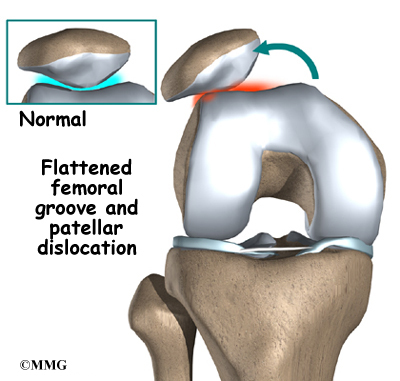

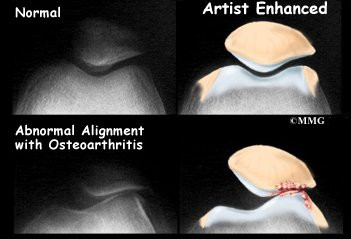

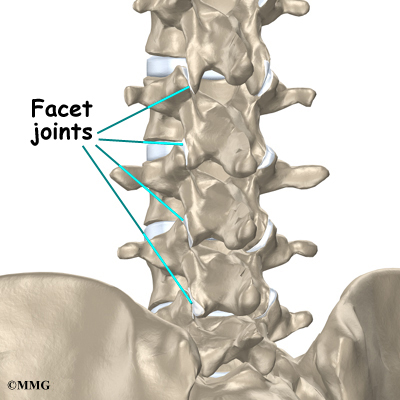

Posture and Joint Alignment

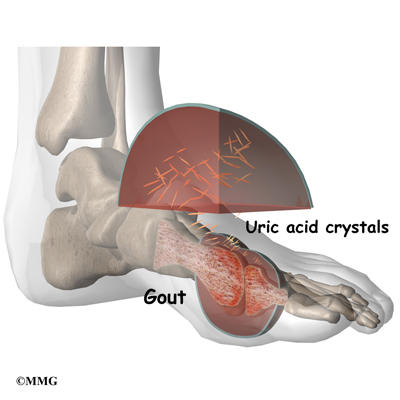

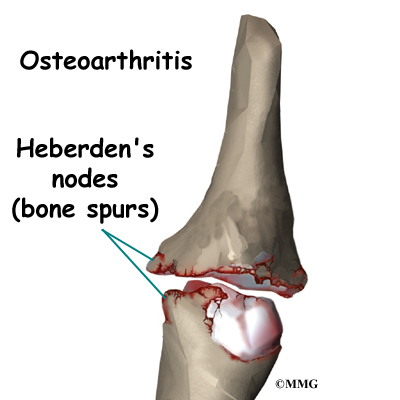

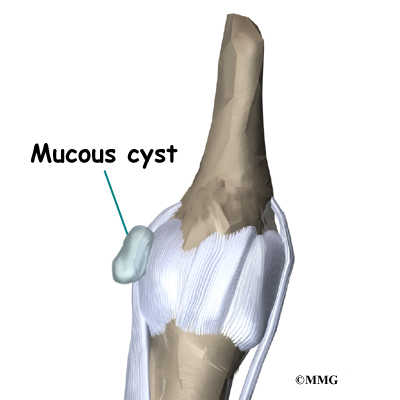

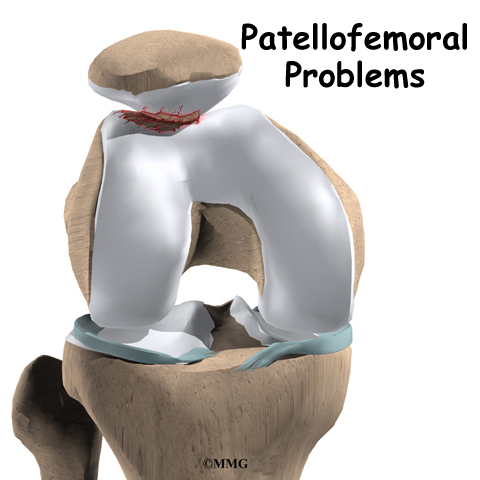

By checking your overall posture and joint alignment, your therapist can see if you have swelling or other signs of inflammation. Your therapist will also look to see if you have any nodules or other changes around a joint that may be present with various forms of arthritis.

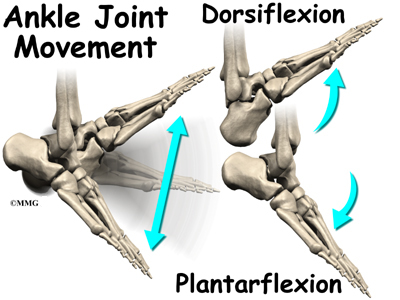

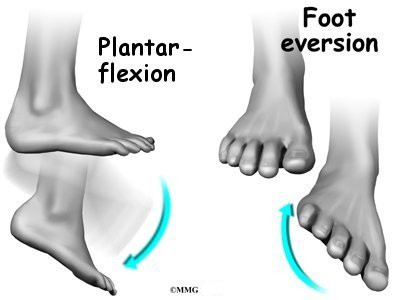

Range of Motion (ROM)

Your therapist will check the ROM in your sore joints. This is a measurement of how far you can move the joint in different directions. Your ROM is written down to compare how much improvement you are making with the treatments.

Strength

Your strength is tested by having you hold against resistance as your therapist tests the muscles around the sore area. Weakness and pain with these tests may be expected due to the presence of arthritis.

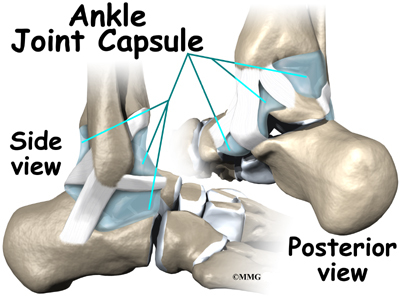

Manual examination

Carefully moving the joint in different positions can give your therapist an idea of the stiffness in your joints.

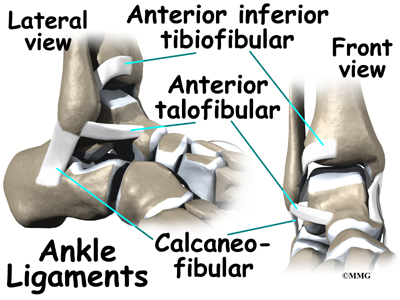

Palpation

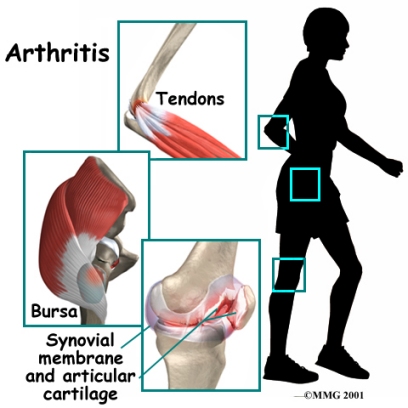

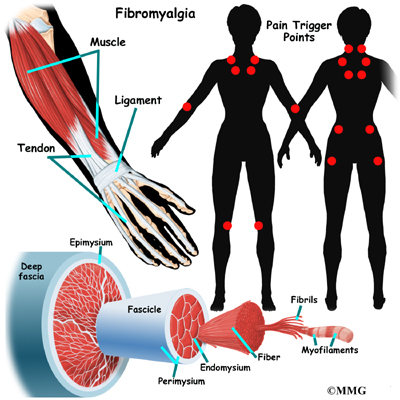

Your therapist will feel the soft tissues around the sore areas. This is called palpation. Through palpation, the therapist checks for changes in skin temperature and any swelling. The therapist also pinpoints sore areas and looks for tender points or spasm in the muscles around the sore area. Palpation is important in helping your therapist decide which treatments to recommend.

Planning Your Care

What goes into a rehabilitation plan?

All the information you give the therapist, along with the results of the manual exam, will be used to create a rehab program especially for you. Your therapist will put together a treatment plan that describes the goals you and your therapist have for the treatment. The plan lists the exercises and treatments that will be used, and it includes an estimate of how many visits you will need over what period of time. Your therapist will also let you know what results to expect from the program.

Therapy Treatments

What kind of treatments and activities might the therapist recommend?

Controlling Your Symptoms

Rehabilitation therapy, combined with drugs and other treatments prescribed by your doctor, can help you manage the pain and swelling in your joints. Your therapist’s recommendations will depend on your specific symptoms and needs and may include one or more of the following treatment choices.

Rest

Knowing when to rest painful joints can help ease arthritis pain. Rest is especially important during flare-ups. As a common sense rule, if a certain activity or movement causes severe pain, avoid doing it. If you can’t avoid it, do it less, or take breaks that let your joints rest.

Your therapist may make you a special resting splint to support your sore joint when you’re not using it. A resting splint keeps the joint properly aligned, which limits pain and prevents joint deformity.

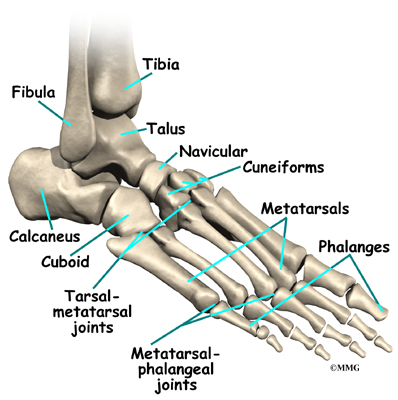

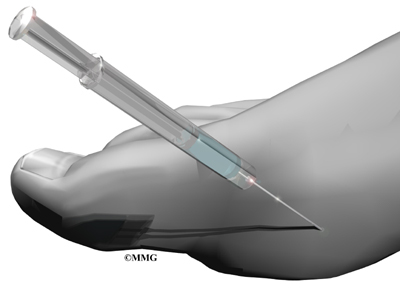

Heat

Heat makes blood vessels expand, which is called vasodilation. Vasodilation helps flush away chemicals that make your joints and muscles hurt. It also helps your muscles relax. Moist hot packs, heating pads, and warm showers or baths are the most effective forms of heat therapy. Heat treatments usually involve applying heat to the sore area for fifteen to twenty minutes. Paraffin baths or warm whirlpools can be especially helpful for joints of the hands or feet. You may find you have less pain and better mobility after applying heat.

Be cautious when using heat. While heat can be very helpful at times, heat can make serious inflammation worse. And even when heat is the best treatment for your discomfort, hotter is not better. Your skin can overheat and even burn. Sleeping with an electric hot pad is a bad idea. The prolonged heat can actually burn your skin.

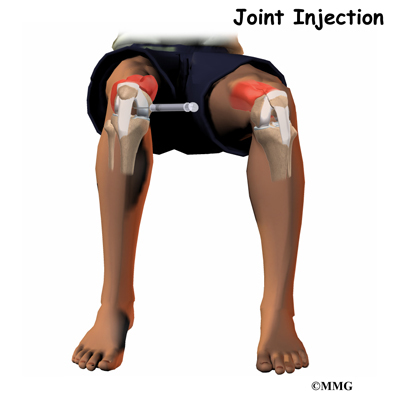

Electrical Stimulation

Gentle electrical currents through the skin can help ease pain and decrease swelling. Electrical stimulation eases pain by replacing pain impulses with the impulses of the electrical current. Once the pain lets up, the muscles begin to relax, making movement and activity easier.

Topical Creams

Certain creams rubbed on the skin can give temporary relief to sore joints. The rubbing is relaxing, and the creams create feelings of warmth or coolness that are soothing. Capsaicin, a cream derived from the common pepper plant, has been shown to effectively relieve arthritis pain. With all creams, you need to wash your hands after using them. What feels good on your sore joint does not feel good in your eyes.

Therapeutic Exercise and Functional Training

Whether at work, home, or play, your capabilities depend on your physical health and function. Specialized treatments and exercises can help maximize your physical abilities, including movement, strength, and general fitness. Therapists also use functional training when you need help doing specific activities with greater ease and safety.

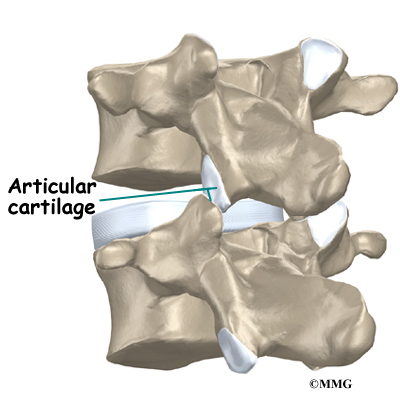

Exercise is safe for arthritis patients. In fact, it’s necessary if you want to improve or maintain joint function. Avoiding exercise just makes your arthritis worse. The less a joint is used, the weaker and stiffer it becomes. This leads to even more pain. Even if you don’t have much range of motion in a joint, your therapist can help you find ways of stretching and moving that can help strengthen your joint. There are some specific types of exercises that therapists recommend especially for people with arthritis.

Stretching

Gentle stretching lengthens muscles and helps the joint maintain its shape and mobility. Therapists teach specific stretches for different types of joints.

Strengthening

Your therapist will teach you exercises that have been adapted especially for arthritic joints. Isometric exercises involve tightening muscles without moving joints. This allows you to keep the muscles strong without stressing your joints. Isometrics can often be done even during flare-ups.

Muscles themselves are not part of joints. But strong muscles around a joint help joints move with less pain. Toned muscles act as shock absorbers in protecting the joint.

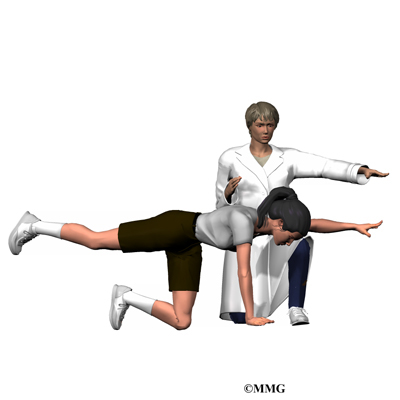

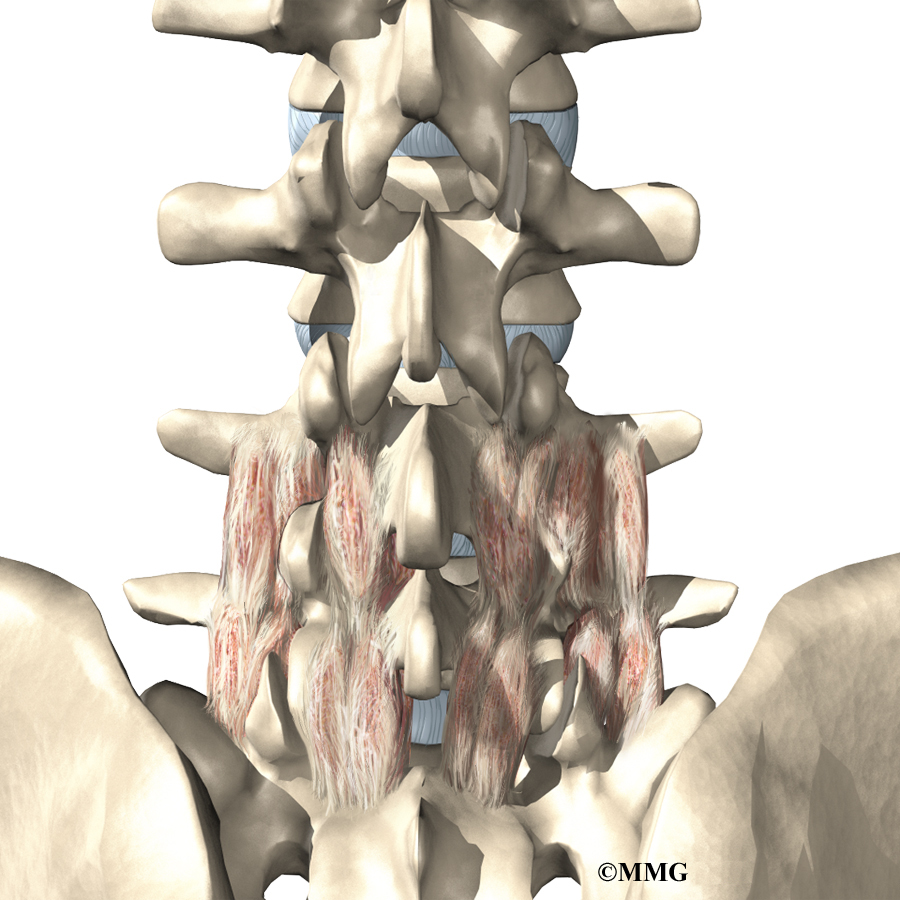

Stabilizing

There are also specific stabilization exercises to help keep your joints aligned. When your joints are positioned correctly, there is less rubbing or overstretching, and therefore less pain. Correct alignment also helps prevent joint deformities.

Pool Therapy

When you exercise in a swimming pool, the water bears some of your weight. This puts less stress on the joints of your feet, ankles, knees, and hips. The water’s buoyancy lets you move easier, and the water’s warmth can relax your muscles. You will probably start pool therapy in a group led by an instructor. If it is helpful, you may continue the exercises on your own. The warmth of the water can help relax muscles, improve circulation, and ease soreness.

Aerobic Exercise

Your therapist and doctor will probably also recommend that you do some kind of aerobic exercise. Doctors generally recommend thirty minutes of moderate activity, at least five days a week. People with arthritis can safely try exercises such as walking, swimming, stationary biking, and low-impact aerobics. Your doctor or therapists can suggest an exercise program based on your condition and your overall health. Keeping your body fit is important for your general health and can help keep your arthritis under control.

Aerobic exercise also helps you manage your weight. Weight control is especially important for people with arthritis in the hips, knees, feet, and spine. Keeping your weight down can do a lot to help you control your symptoms.

No matter what type of exercise you do, you should not feel extra pain in the joints while you exercise. Your joints may be sore after exercising, but the soreness should be mild and go away within a short period of time.

Lifestyle Management and Functional Training

It is important that you be very open with your therapist about the ways your disease affects your daily activities. Your therapists can suggest ways to help you reduce the effort it takes to do difficult tasks.

Special Devices

There are many different kinds of equipment available to help you minimize the stress on your joints while you do daily tasks around the house or at work. What kind of equipment you need depends on which joints are affected. Canes and walkers help ease the stress on your weight-bearing joints. Raising the height of chairs and toilet seats can make it easier for you to sit down and stand up. Reachers or grabbers can help you pick up items from the floor without having to bend or stoop. There are devices to help with buttoning, putting on socks, or using zippers. A rolling cart is easier to haul around with arthritic fingers than a hand-held briefcase.

Your therapist may also suggest special splints or braces. A working splint keeps the joints aligned as you go about your daily activities. Splints are made for specific joints and specific activities.

Your therapist may also recommend simple changes in equipment. For example, a good pair of shoes can help reduce shock. If you walk or stand for long periods of time, you should try to do it on soft surfaces. As another example, women may choose a shoulder bag or a small backpack to take the place of a clutch purse or brief case if they have problems with the joints in their hands.

Ergonomics

When they hear the word ergonomics, most people think of the way their desk and computer are set up at work. The meaning is larger than that. Ergonomics considers the way you use your body when you take part in certain activities.

Rehabilitation therapists examine your workstation to help determine if you need to make changes. Your therapist will pay special attention to your posture, the repetitions involved in your work, rest times, the amount of weight you are working with, and which activities seem to cause you the most problems. Your therapist will look at the heights of your chair and desk, alignment of computer monitors, lighting, and any special equipment you use.

After evaluating your work site, your therapist will make recommendations. If changes are suggested, they are usually small and inexpensive, such as changing the height of your chair or standing in a different position. But even these minor changes can make big differences in your discomfort on the job.

The ideas behind ergonomics can also be applied to the tasks you do at home. If you have problems with specific jobs or hobbies, talk to your therapist. Together you may come up with a plan or some simple devices that can help.

Pacing Yourself

Plan to take breaks. Pace your activities so that you don’t get too tired or have to force your joint to function through pain.

Taking Care of Your Mind

Not all your work will be physical. Dealing with the pain and loss of function of arthritis can be emotionally draining. Make sure you take care of yourself mentally, and try to bolster your coping skills. Breathing exercises, naps, visual imagery, and meditation can all help you relax. Learning more about your condition can help you feel more in control of your disease. Many people find support groups helpful.

Home Program

Your therapist’s goal is to help you figure out ways to keep your pain under control and improve your strength and range of motion. When you are well under way, your regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource for you, but you will be in charge of your own ongoing rehabilitation program.