A Patient’s Guide to Adhesive Capsulitis

Introduction

Many adults (mostly women) between the ages of 40 and 60 years of age develop shoulder pain and stiffness called adhesive capsulitis. You may be more familiar with the term frozen shoulder to describe this condition. But frozen shoulder and adhesive capsulitis are actually two separate conditions.

This guide will help you understand

- what causes adhesive capsulitis

- what tests your doctor will do to diagnose it

- how you can regain use of your shoulder.

Anatomy

What part of the shoulder is affected?

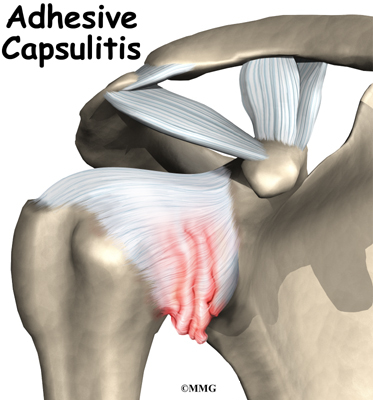

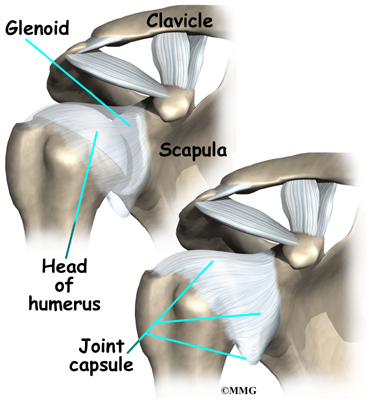

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone). The joint capsule is a watertight sac that encloses the joint and the fluids that bathe and lubricate it. The walls of the joint capsule are made up of ligaments. Ligaments are soft connective tissues that attach bones to bones. The joint capsule has a considerable amount of slack, loose tissue, so the shoulder is unrestricted as it moves through its large range of motion.

The terms frozen shoulder and adhesive capsulitis are often used interchangeably. In other words, the two terms describe the same painful, stiff condition of the shoulder no matter what causes it. A more accurate way to look at this is to refer to true adhesive capsulitis (affecting the joint capsule) as a primary adhesive capsulitis.

As the name suggests, adhesive capsulitis affects the fibrous ligaments that surround the shoulder forming the capsule. The condition referred to as a frozen shoulder usually doesn’t involve the capsule. Secondary adhesive capsulitis (or true frozen shoulder) might have some joint capsule changes but the shoulder stiffness is really coming from something outside the joint. Some of the conditions associated with secondary adhesive capsulitis include rotator cuff tears, biceps tendinitis, and arthritis. In either condition, the normally loose parts of the joint capsule stick together. This seriously limits the shoulder’s ability to move, and causes the shoulder to freeze.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Causes

Why did my shoulder freeze up?

The cause or causes of either primary adhesive capsulitis or secondary adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) remain largely a mystery. Some of the risk factors for adhesive capsulitis include diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, and autoimmune diseases. Anyone who has had a heart attack, stroke, or been treated for breast cancer is also at increased risk for this condition. But a significant number of people develop adhesive capsulitis without any known trauma, medical history, or other risk factor.

In the case of secondary adhesive capsulitis (true frozen shoulder), the problem is really coming from something outside the joint. Some of the conditions associated with secondary adhesive capsulitis include rotator cuff tears, impingement, bursitis, biceps tendinitis, and arthritis.

For either type, an overactive immune response or an autoimmune reaction may be at fault. In an autoimmune reaction, the body’s defense system, which normally protects it from infection, mistakenly begins to attack the tissues of the body. This causes an intense inflammatory reaction in the tissue that is under attack.

No one knows why this occurs so suddenly. Pain and stiffness may begin after a shoulder injury, fracture, or surgery. It can also start if the shoulder is not being used normally. This can happen after a wrist fracture, when the arm is kept in a sling for several weeks. For some reason, immobilizing a joint after an injury seems to trigger the autoimmune response in some people.

Doctors theorize that the underlying condition may cause chronic inflammation and pain that make you use that shoulder less. This sets up a situation that can create adhesive capsulitis. With a primary adhesive capsulitis, treatment of any associated risk factors or underlying medical conditions may be needed before working to correct the tissues around the shoulder. In the case of secondary adhesive capsulitis, it may be necessary to treat the shoulder first in order to regain its ability to move before the underlying musculoskeletal problem can be addressed..

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Impingement Syndrome

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Rotator Cuff Tears

Symptoms

What are the symptoms of adhesive capsulitis?

The symptoms of adhesive capsulitis (and frozen shoulder) are primarily shoulder pain and stiffness, resulting in a very reduced range of shoulder motion. The tightness in the shoulder can make it difficult to do regular activities like getting dressed, combing your hair, or reaching across a table.

Diagnosis

What tests will my doctor run?

The diagnosis of adhesive capsulitis is usually made on the basis of your medical history and physical examination. One key finding that helps differentiate adhesive capsulitis from a frozen shoulder is how the shoulder moves. With adhesive capsulitis, the shoulder motion is the same whether the patient or the doctor tries to move the arm. With a frozen shoulder, say from a tendinitis or rotator cuff tear, the patient cannot move the arm normally or through the full range of motion. But when someone else lifts the arm it can be moved in a nearly normal range of motion.

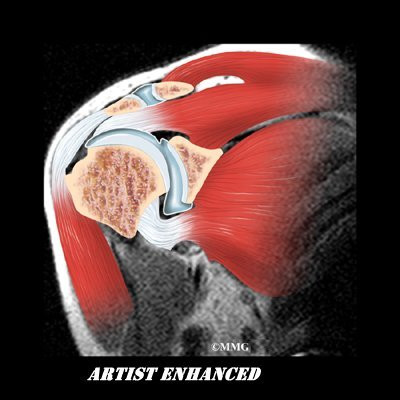

Simple X-rays are usually not helpful. An arthrogram may show that the shoulder capsule is scarred and tightened. The arthrogram involves injecting dye into the shoulder joint and taking several X-rays. In adhesive capsulitis, very little dye can be injected into the shoulder joint because the joint capsule is stuck together, making it smaller than normal. The X-rays taken after injecting the dye will show very little dye in the joint.

As your ability to move your shoulder increases, your doctor may suggest additional tests to differentiate between primary adhesive capsulitis and secondary adhesive capsulitis (from an underlying condition, such as impingement or a rotator cuff tear). Probably the most common test used is magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI scan is a special imaging test that uses magnetic waves to create pictures that show the tissues of the shoulder in slices. The MRI scan shows tendons and other soft tissues as well as the bones.

The final and most accurate diagnosis is made when an arthroscopic exam is done. The arthroscopic exam makes it possible to identify exactly which stage of disease you may be in. Tissue samples taken from inside and around the joint are examined under a microscope.

Four separate stages of primary adhesive capsulitis have been recognized from arthroscopic tissue sampling. Symptoms present at any given time usually correspond to the stage you are in. In the first stage, pain prevents full active shoulder motion (active motion means you move your own shoulder) but full passive motion (an examiner moves your shoulder without help from you) is still available. There are some inflammatory changes in the synovium but the capsular tissue is still normal.

In stage two (the freezing stage), pain is now accompanied by stiffness and you start to lose full passive shoulder motion. External rotation is affected first. The rotator cuff remains strong. These two symptoms differ from secondary adhesive capsulitis (what might otherwise be called a frozen shoulder). The condition referred to as a frozen shoulder is more often characterized by damage to the rotator cuff and loss of internal rotation first.

The pain during stage two of primary adhesive capsulitis is worse at night. Cellular changes continue to progress with increased blood flow to the synovium. There are early signs of scarring of the capsule from the inflammatory and repair processes.

By stage three of primary adhesive capsulitis (the frozen stage), there is less pain (mostly at the end range of motion) but more stiffness. There is a true loss of active and passive shoulder joint motion. Very little if any inflammation is seen in the tissue samples viewed under a microscope. Instead, the pathologist sees much more fibrotic (scar) tissue.

In the final (chronic) stage (stage four) you don’t have pain but instead there is profound stiffness and significant loss of motion. Both of these symptoms will gradually start to get better. The body is no longer attempting to repair or correct the problem. Enough scar tissue is present to make it difficult for the surgeon to see the joint during arthroscopic examination.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

Treatment is based on any underlying causes (if known), any risk factors present, and the stage at the time of diagnosis. There isn’t a one-best-treatment known for adhesive capsulitis. Studies done so far just haven’t been able to come to a single evidence-based set of treatment guidelines for this problem.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Treatment of adhesive capsulitis can be frustrating and slow. Most cases eventually improve, but the process may take months. The goal of your initial treatment is to decrease inflammation and increase the range of motion of the shoulder. Your doctor will probably recommend anti-inflammatory medications, such as aspirin and ibuprofen.

During the early stage, your doctor may also recommend an injection of cortisone and a long-acting anesthetic, similar to lidocaine, to get the inflammation under control. Cortisone is a steroid that is very effective at reducing inflammation. Controlling the inflammation relieves some pain and allows the stretching program to be more effective.

Physical or occupational therapy treatments are a critical part of recovery and rehab. The first two goals are to reduce pain and interrupt the inflammatory cycle. Treatments are directed at getting the muscles to relax in order to help you regain the motion and function of your shoulder. This can be done with modalities such as electrical stimulation, joint mobilization, the use of cold, and iontophoresis. Iontophoresis is a way to push medications through the skin directly into the inflamed tissue.

Therapists use heat and hands-on treatments to stretch the joint capsule and muscle tissues of the shoulder. In some cases, it helps to inject a long-acting anesthetic with the cortisone right before a stretching session. This allows your therapist to manually break up the adhesions while the shoulder is numb from the anesthetic. You will also be given exercises and stretches to do as part of a home program. You may need therapy treatments for three to four months before you get full shoulder motion and function back.

During stage two, the therapist will address the capsular tightness and adhesions. Joint mobilization techniques are used to keep the joint sliding and gliding smoothly and to prevent scar tissue from forming. Keeping full shoulder and scapular (shoulder blade) motion is a priority. Special stretching techniques are used to prevent pain that could cause muscles around the shoulder to tighten even more.

Physical therapy throughout stages three and four continues in a similar fashion with added strengthening exercises.

Physical or occupational therapy treatments are a critical part of helping you regain the motion and function of your shoulder. Treatments are directed at getting the muscles to relax. Therapists use heat and hands-on treatments to stretch the joint capsule and muscle tissues of the shoulder. You will also be given exercises and stretches to do as part of a home program. You may need therapy treatments for three to four months before you get full shoulder motion and function back.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Joint Injections for Arthritis

Surgery

Manipulation Under Anesthesia

If progress in rehabilitation is slow, your doctor may recommend manipulation under anesthesia. This means you are put to sleep with general anesthesia. Then the surgeon aggressively stretches your shoulder joint. The heavy action of the manipulation stretches the shoulder joint capsule and breaks up the scar tissue. In most cases, the manipulation improves motion in the joint faster than allowing nature to take its course. You may need this procedure more than once.

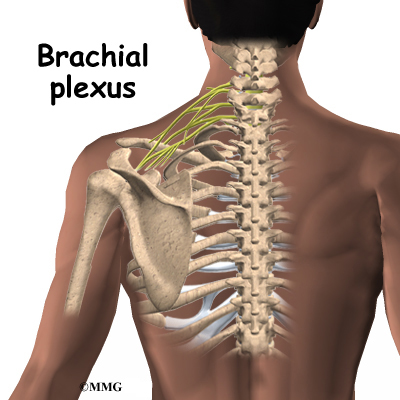

This procedure has risks. There is a very slight chance the stretching can injure the nerves of the brachial plexus, the network of nerves running to your arm. And there is a risk of fracturing the humerus (the bone of the upper arm), especially in people who have osteoporosis (fragile bones).

Arthroscopic Release

When it becomes clear that physical therapy and manipulation under anesthesia have not improved shoulder motion, arthroscopic release may be needed. This procedure is usually done using an anesthesia block to deaden the arm. The surgeon uses an arthroscope to see inside the shoulder. An arthroscope is a slender tube with a camera attached. It allows the surgeon to see inside the joint.

During the arthroscopic procedure, the surgeon cuts (releases) scar tissue, the ligament on top of the shoulder (coracohumeral ligament), and a small portion of the joint capsule. During the arthroscopic procedure a biopsy of the scar tissue is sent to the lab for evaluation to determine the stage of adhesive capsulitis. If shoulder movement is not regained or if the surgeon is unable to complete the surgery using the arthroscope, an open procedure may be needed. An open procedure requires a larger incision so the surgeon can work in the joint more easily.

At the end of the release procedure, the surgeon gently manipulates the shoulder to gain additional motion. A steroid medicine may be injected into the shoulder joint at the completion of the procedure.

Nerve Block

Numbing the suprascapular nerve to the shoulder is a newer technique used in some pain clinics. The procedure can be done on an outpatient basis, which means you’ll be in and out the same day. A single injection of a numbing agent combined with a steroid medication temporarily eliminates the pain signals. It’s like hitting a “reset” button. The nerve pathway sending continuous pain signals from the shoulder to the spinal cord and up to the brain is turned off. For a short time, the patient can move the arm fully without pain. Often, that’s enough to get the shoulder back on track for improved movement and function.

Hydrodilation

Another new technique called hyrdodilation or brisement is being used as an alternative to surgery. A fluid is injected into the joint causing the capsule to expand until it bursts. The result can be relief of pain and improved function. There haven’t been enough studies done yet to see how well this approach works. And there have been no studies comparing hydrodilation with manipulation or nerve block.

Rehabilitation

What can I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

The primary goal of physical therapy is to help you regain full range of motion in the shoulder. If your pain is too strong at first to begin working on shoulder movement, your therapist may need to start with treatments to help control pain. Treatments to ease pain include ice, heat, ultrasound, and electrical stimulation. Therapists also use massage or other types of hands-on treatment to ease muscle spasm and pain.

When your shoulder is ready, therapy will focus on regaining your shoulder’s movement. Sessions may begin with treatments like moist hot packs or ultrasound. These treatments relax the muscles and get the shoulder tissues ready to be stretched. Therapists then begin working to loosen up the shoulder joint, especially the joint capsule. You can also get a good stretch using an overhead shoulder pulley in the clinic or as part of a home program.

If your doctor recommends an injection for your shoulder, you should plan on seeing your therapist right after the injection. The extra fluid from the injection stretches out the tissues of the joint capsule. An aggressive session of stretching right afterward can help maximize the stretch to the joint capsule.

After Surgery

After arthroscopic release, you’ll likely begin using a shoulder pulley on a daily basis. You’ll probably be encouraged to use the treated arm in everyday activities. Strengthening exercises are not begun for four to six weeks after the procedure. You might participate in physical or occupational therapy for up to two months after arthroscopic release.

After manipulation under anesthesia, your surgeon may place your shoulder in a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine. CPM is used after many different types of joint surgeries. You begin using CPM immediately after surgery. It keeps the shoulder moving and alleviates joint stiffness. The machine simply straps to the arm and continuously moves the joint. This continuous motion is thought to reduce stiffness, ease pain, and keep extra scar tissue from forming inside the joint.

Some surgeons apply a dynamic splint to the shoulder after manipulation surgery. A dynamic splint puts the shoulder into a full stretch and holds it there. Keeping the shoulder stretched gradually loosens up the joint capsule.

You’ll resume therapy within one to two days of the shoulder manipulation. Some surgeons have their patients in therapy every day for one to two weeks. Your therapist will treat you with aggressive stretching to help maximize the benefits of the shoulder manipulation. The stretching also keeps scar tissue from forming and binding the capsule again. Your shoulder movement should improve continually after the manipulation and therapy. If not, you may require more than one manipulation.

Once your shoulder is moving better, treatment is directed toward shoulder strengthening and function. These exercises focus on the rotator cuff and shoulder blade muscles. Your therapist will help you retrain these muscles to help keep the ball of the humerus centered in the socket. This lets your shoulder move smoothly during all your activities.

The therapist’s goal is to help you regain shoulder motion, strength, and function. When you are well under way, regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.