A Patient’s Guide to Osteoporosis

Introduction

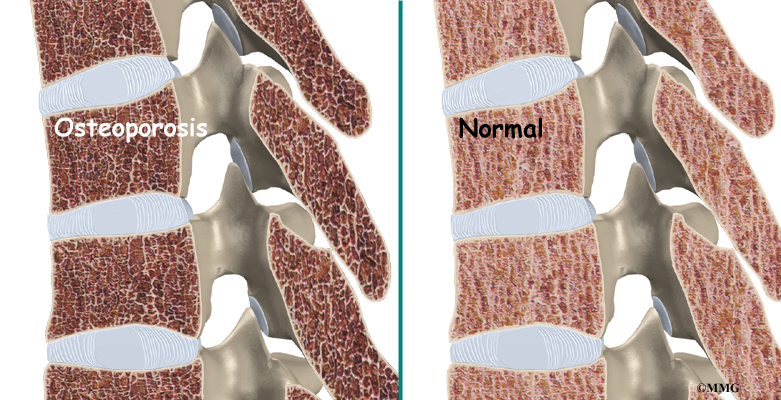

Osteoporosis is a very common disorder affecting the skeleton. In a patient with osteoporosis, the bones begin losing their minerals and support beams, leaving the skeleton brittle and prone to fractures.

In the U.S., 10 million individuals are estimated to already have the disease and almost 34 million more have low bone mass, placing them at increased risk for osteoporosis. Of the 10 million Americans affected by osteoporosis, eight million are women and two million are men. Most of them over age 65.

Bone fractures caused by osteoporosis have become very costly. Half of all bone fractures are related to osteoporosis. More than 300,000 hip fractures occur in the United States every year. A person with a hip fracture has a 20 percent chance of dying within six months as a result of the fracture. Many people who have a fracture related to osteoporosis spend considerable time in the hospital and in rehabilitation. Often, they need to spend some time in a nursing home.

This guide will help you understand

- what happens to your bones when you have osteoporosis

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what you can do to slow or stop bone loss

Anatomy

What happens to bones with osteoporosis?

Most people think of their bones as completely solid and unchanging. This is not true. Your bones are constantly changing as they respond to the way you use your body. As muscles get stronger, the bones underneath them get stronger, too. As muscles lose strength, the bones underneath them weaken. Changes in hormone levels or the immune system can also change the way the bones degenerate and rebuild themselves.

As a child, your bones are constantly growing and getting denser. At about age 25, you hit your peak bone mass. As an adult, you can help maintain this peak bone mass by staying active and eating a diet with enough calories, calcium, and vitamin D. But maintaining this bone mass gets more difficult as we get older. Age makes building bone mass more difficult. In women, the loss of estrogen at menopause can cause the bones to lose density very rapidly.

The bone cells responsible for building new bone are called osteoblasts. Stimulating the creation of osteoblasts helps your body build bone and improve bone density. The bone cells involved in degeneration of the bones are called osteoclasts. Interfering with the action of the osteoclasts can slow down bone loss.

In high-turnover osteoporosis, the osteoclasts reabsorb bone cells very quickly. The osteoblasts can’t produce bone cells fast enough to keep up with the osteoclasts. The result is a loss of bone mass, particularly trabecular bone–the spongy bone inside vertebral bones and at the end of long bones. Postmenopausal women tend to have high-turnover osteoporosis (also known as primary type one osteoporosis). This relates to their sudden decrease in production of estrogen after menopause. Bones weakened by this type of osteoporosis are most prone to spine and wrist fractures.

In low-turnover osteoporosis, osteoclasts are working at their normal rate, but the osteoblasts aren’t forming enough new bone. Aging adults tend to have low-turnover osteoporosis (also known as primary type two osteoporosis). Hip fractures are most common in people with this type of osteoporosis.

Secondary osteoporosis describes bone loss that is caused by, or secondary to, another medical problem. These other problems interfere with cell function of osteoblasts and from overactivity of osteoclasts. Examples include medical conditions that cause inactivity, imbalances in hormones, and certain bone diseases and cancers. Some medications, especially long term use of corticosteroids, are known to cause secondary osteoporosis due to their impact on bone turnover.

Osteoporosis creates weak bones. When these weak bones are stressed or injured, they often fracture. Fractures most often occur in the hip or the bones of the spine (the vertebrae). They can also occur in the upper arm, wrist, knee, and ankle.

Causes

What causes osteoporosis?

Aging is one of the main risk factors for osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures. If you are lucky enough to live a long life, you are much more likely to develop weakened bones from osteoporosis. In women, the loss of estrogen in menopause causes bone loss of up to two percent per year. White women over age 50 have a lifetime risk of fracture of about 50 percent. This figure increases with increasing age.

A number of factors contribute to osteoporosis:

- advanced age

- female gender

- low body weight or a thin and slender build

- recent weight loss

- history of fractures

- family history of fractures

- tobacco use

- alcohol abuse

- lack of exercise

- extended use of certain medications (e.g., corticosteroids, anticonvulsants, and thyroid medicine)

- Asian or Caucasian race

These risk factors are just as important as a measurement of low bone mass in determining how likely you are to have a fracture. People with low bone mass but no additional risk factors often don’t develop fractures. People with small amounts of bone loss but many risk factors are more likely to eventually develop fractures.

Symptoms

What does osteoporosis feel like?

Fractures caused by osteoporosis are often painful. But osteoporosis itself has no symptoms. That is why it is especially important to get tested if you are a woman past menopause and have any of the above risk factors. Women over 65 should be tested whether or not they have other risk factors. People with other bone problems or who take drugs that weaken the bones should also be tested. An initial screening for osteoporosis is painless and easy.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose osteoporosis?

Free osteoporosis screenings are available in many drug stores and malls. Most of these screenings use a machine that scans the bone in the heel of your foot. It is a fast and simple way to get an idea of your bone density. However, this test is not entirely accurate. Because the heel bears a lot of weight, the test may show normal bone in the heel, even though the hipbones or spine may have low bone density. If the foot scan shows a low bone mass, you should talk to your doctor.

Your doctor will take a detailed medical history to help weigh your risk factors for osteoporosis. Information about your lifestyle and diet will also help your doctor develop a plan to help you build or maintain bone density.

Your doctor may also recommend more precise testing. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is the most common method of measuring bone mass. A DEXA test uses special X-rays of the bones of your hip and spine to show your bone mass in these areas. The bone mass is then compared to that of a healthy thirty-year-old, called a T score. If you are within one standard deviation (SD) for bone density, you have normal bone. (SD is a statistic to measure variations in how a group is distributed.) If you are between one and 2.5 SDs below ideal levels, you are considered to be osteopenic. This means you have a mild form of osteoporosis. If the bone mass is more than 2.5 SDs below ideal levels, you have osteoporosis.

Be aware that DEXA scans are not perfect. Different equipment or different technicians can get somewhat different readings. If you need to have more precise data, your doctor may recommend additional types of bone scans or ultrasound tests.

A single DEXA scan also can’t show your doctor whether your bone mass is stable, increasing, or decreasing. Your doctor may have you take certain medications that create markers in the blood or urine to show what is happening in your bones. These tests will tell your doctor if you have high-turnover or low-turnover osteoporosis.

If bone density tests show that you have weakened bones, your doctor will need to rule out other causes. In some cases, problems with bone marrow or hormone levels can cause bone loss. Blood tests can show these conditions.

In other cases the bone weakening is actually from a condition called osteomalacia. Osteomalacia involves a softening of the bones caused by a lack of vitamin D. Vitamin D in your body comes from food and sunlight. Due to a lack of sunlight, almost 10 percent of people with hip fractures in the northern parts of the world have osteomalacia rather than osteoporosis. Urine and blood tests can help rule out osteomalacia.

In some cases, your primary care physician may refer you to a specialist. If you still have significant bone loss while on medication to prevent bone resorption, you may need to see a specialist. Referral is also advised for patients who have recurring fractures during therapy or repeated, unexplained fractures. Your doctor will help you find the right specialist for your situation.

Treatment Options

What can be done for osteoporosis?

The goal of your treatment plan will be to prevent fractures. This is especially important if you’ve already suffered a fracture from osteoporosis. To prevent fractures, you need to increase your bone mass. If you have high-turnover osteoporosis, you also need to prevent rapid bone reabsorption.

You need to take several steps to increase your bone mass

- Make sure you get enough calcium and vitamin D. (Vitamin D helps your body absorb calcium.) Researchers think that increased calcium intake alone could reduce the number of fractures by 10 percent. More and more of us don’t get enough calcium and vitamin D, especially as we age. It is difficult to get recommended levels from the food we eat, so supplements are probably necessary. Talk to your doctor about what kind to buy. Calcium comes in many forms–for example, calcium carbonate, calcium citrate, calcium phosphate, and calcium from bone meal. Some forms of calcium need to be taken with food, and others need to be taken with certain types of food. Taking extra calcium and vitamin D improves the effectiveness of all other treatments for osteoporosis.

- Eat enough calories to maintain a healthy weight. Being too thin increases your risk of osteoporotic fractures. Weight loss can be a cause of bone loss.

- Exercise. Your bones are constantly adjusting to the demands you put on them. Even low levels of exercise can help you maintain better bone mass. Low-impact exercises like fast walking, stair climbing, and safe forms of dance help stimulate osteoblasts, slowing down reabsorption. Muscle-strengthening exercises, using light weights, can help keep the bones underneath the muscles strong. Balance training can help you prevent the falls that can cause fractures. Your doctor may recommend seeing a physical therapist to help you develop an exercise program with all three kinds of exercises. (See below.)

- Premenopausal women should avoid overtraining and certain eating disorders, which can cause missed periods (amenorrhea).

- If you smoke, quit immediately.

- If you drink alcohol, do so moderately.

Medication

If you follow these recommendations and still have significant bone loss, your doctor may prescribe medications to slow down your body’s reabsorption of bone.

Many drugs are now available for the prevention and/or treatment of osteoporosis. Finding the right drug for each patient takes into consideration benefits and risks of the drug. These are matched against specific patient characteristics and risk factors. Ultimately, the best drug is the one most likely to be taken consistently and/or correctly by the patient. Osteoporosis management is most effective when drugs are taken in such a way that they have their full benefit.

If you are past menopause, hormone replacement therapy can be very effective. Bisphosphonates and calcitonin can also slow your body’s reabsorption of bone.

Studies have shown that 80 percent of women actually build bone mass up to two percent per year while on estrogen replacement therapy. Estrogen has been shown to decrease the occurrence of fractures in the vertebrae by 50 percent and fractures in the hip by 25 percent. Studies have also shown that hormone replacement therapy can also lower rates of coronary artery disease, relieve some symptoms of menopause, and maybe even prevent or postpone Alzheimer’s disease.

Hormone replacement therapy worries many women. Studies have shown that it may increase the risk of breast cancer. For women with a family history of breast cancer or who have had a stroke or thrombophlebitis (blood clots), hormone replacement therapy is probably not appropriate. Other women should at least consider taking estrogen. Its effects on osteoporosis are dramatic. Researchers estimate that, if estrogen were widely used, it could reduce all osteoporotic fractures by 50 to 75 percent.

Hormone replacement therapy must be continued to be effective, however. When a woman stops taking estrogen, she’ll start to lose bone at a very fast rate again. Within seven years, her bone density will be as low as that of a woman who never took estrogen.

Doctors often prescribe calcitonin to patients with fractures. Calcitonin is a non-sex, non-steroid hormone. Calcitonin binds to osteoclasts (the bone cells that reabsorb bone) and decreases their numbers and activity levels. Calcitonin used to be given only by injection, but now it is available in a nasal spray and a rectal suppository. Nasal calcitonin is used most often for women with osteoporosis who are five years or more past menopause and unable to take other approved agents. For unknown reasons, calcitonin seems to relieve pain. Calcitonin from salmon is much more effective than calcitonin from humans.

You and your doctor need to work together to monitor the effects of calcitonin. It is a new drug, and its long-term effects and benefits are still not fully known. More than 20 percent of patients develop a resistance to calcitonin over time, and it stops working for them.

Bisphosphonates also slow reabsorption by affecting the osteoclasts. The FDA has approved a variety of bisphosphonates for the treatment of osteoporosis. You may have heard the names of some of these such as Alendronate (Fosamax), Risedronate (Actonel), or Ibandronate (Boniva).

Some bisphosphonates are taken orally (pill form) on a daily basis. Others are available in weekly or monthly doses. A new injectable bisphosphonate (Zoledronate) can be given annually (once a year). Boniva comes in pill form and can also be injected once every three months. The injectable forms of this drug are used in the management of postmenopausal osteoporosis.

Studies have shown that bisphosphonates increase bone mass and prevent fractures. No one is sure how well bisphosphonates work when used for a long time. But stopping the drug doesn’t seem to cause the rapid bone loss that happens when someone stops taking estrogen. Because there can be some side effects with these medications, you need to work closely with your doctor if you take them.

The FDA is currently studying several drugs that may be used to treat osteoporosis. Some of these drugs, such as sodium fluoride, can be helpful in low-turnover osteoporosis. These drugs affect your osteoblasts in ways that cause them to create more bone. Sodium fluoride may be available in the near future. Other FDA-approved drugs are now available for the treatment of osteoporosis. For example, Raloxifene (Evista) is an anti-estrogen. Anti-estrogens are also called selective estrogen-receptor modifiers (SERMs). SERMs improve bone density and prevent fractures similar to estrogen, yet without increasing the chances of hormone-related cancer. Their main benefit over hormone replacement therapy is that they do not increase the risk of breast cancer.

Raloxifene is used most often for postmenopausal women younger than 65. They must not be at risk for blood clots or have cardiovascular disease. Men may be prescribed the only anabolic agent (Teriparatide/Forteo) approved for the management of osteoporosis. Anabolic usually refers to hormones that build up muscle or bone mass. Forteo is a form of parathyroid hormone used for patients at high risk of fracture. It is usually followed by an agent with antiresorptive effects such as a bisphosphonate.

Lifestyle changes, hormone replacement therapy, exercise prescription, and recent advances in drug therapy can help you take control of your osteoporosis. You and your doctor should be able to find ways to help you prevent the debilitating fractures of osteoporosis.

Physical Therapy

Many patients benefit from working with a physical therapist. People learn safe ways of moving, lifting, and exercising. Treatments also help people gain muscle strength and improved posture.

The physical therapist relies on your test results and the information received by you and your doctor. The therapist also looks at your body height, posture, body movements, strength, flexibility, balance, and your risk for having a fall.

Accurately measuring and recording your body height is a key part of the evaluation. It can give your therapist an idea of how osteoporosis is affecting your bones and posture, and comparing the recordings over a period of time can help track your success with treatments.

Posture exercises are used to help you “be tall”, regaining body height commonly lost with osteoporosis. This training can help patients who have stooped posture, called kyphosis, in the upper part of the spine. In healthy spine posture, the head is balanced on top of the spine rather than jutted forward.

In posture exercises, the goal is to get your body lined up from head to toe, with weight going through your hips. In people with advanced osteoporosis, the upper body is commonly bent forward at the hips. This prevents the hip bones from getting the right amount of stress and weight on them. As a result, the bones weaken and become more prone to fracture.

Your therapist will explain ways you can put good posture into practice. This is called body mechanics–the way you align your body when you do your activities. Remember that healthy posture is balanced with the body aligned from the head to toes. The same posture should be used when you bend forward to pick things up. Instead of rounding out your shoulders and upper back, keep the back in its healthy alignment as you bend forward at the hip joint. This keeps your back in a safe position and prevents the vertebrae from pinching forward. When bones are weakened from osteoporosis, rounding the spine forward when bending and lifting increases the risk of a spine fracture. As the back rounds forward, it pinches the front section of the vertebrae and can cause a fracture.

Your therapist will work with you in designing a safe program of exercise. Weight-bearing exercise strengthens existing bone and the muscles around joints. These types of exercises include walking outdoors or on a treadmill, doing safe forms of dance, and performing resistance training.

Some of the keys to safe exercise for osteoporosis include using good body alignment, avoiding bending or heavy twisting of the trunk, building up the amount of weight and number of repetitions gradually, and being consistent with your exercise program. Avoid exercises that curl your trunk forward such as stationary bike riding, sit-ups, toe-touches, and knee-to-chest exercises. Don’t exercise using abdominal crunch machines or rowing machines. Emphasize exercises that promote upright posture of the spine, such as walking. And do upper body exercises with your back supported in optimal alignment.

Your physical therapist will also check to make sure you have good balance. Poor balance can lead to a hazardous fall. When people with osteoporosis fall, they often end up fracturing a bone–a potentially life-threatening situation. Exercises to improve balance can be as simple as standing on one foot. As your balance gets better, more challenging types of exercises may be given.

People with balance problems can also benefit from practicing tai chi, an exercise form originating in China. In addition to gaining better balance, people who use the exercise movements show improved posture, flexibility, and strength.

Your therapist will continue to compare your test results of body height, posture, balance, and strength to see how well you are improving. The therapist’s goal is to help you become proficient and safe with your exercises, to improve you stature, strength, and flexibility, and to give you tips on how to avoid future problems.

When patients are well underway, regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. The therapist will continue to be a resource, but patients will be in charge of doing their exercises as part of an ongoing home program.