A Patient’s Guide to Ankle Syndesmosis Injuries

Introduction

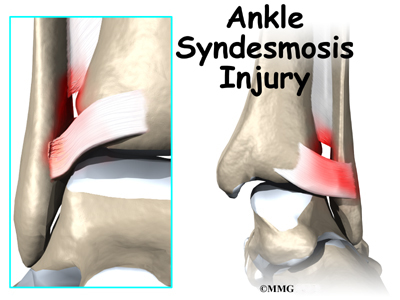

An ankle injury common to athletes is the ankle syndesmosis injury. This type of injury is sometimes called a high ankle sprain because it involves the ligaments above the ankle joint. In an ankle syndesmosis injury, at least one of the ligaments connecting the bottom ends of the tibia and fibula bones (the lower leg bones) is sprained. Recovering from even mild injuries of this type takes at least twice as long as from a typical ankle sprain.

This guide will help you understand

- how ankle syndesmosis injuries occur

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what can be done to treat it

Anatomy

What part of the ankle is involved?

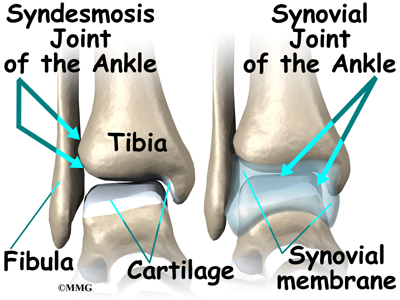

A syndesmosis is a joint where the rough edges of two bones are held together by thick connective ligaments. The connection of the lower leg bones, the tibia and fibula, is a syndesmosis. The tibia is the main bone of the lower leg. The fibula is the small, thin bone that runs down the outer edge of the tibia.

Only a few joints in the body are syndesmosis joints. In addition to the ankle syndesmosis (the connection of the tibia and fibula), syndesmosis joints are also located in the lower spine, where the top of the triangular-shaped sacrum bone fits between the pelvis bones.

Most joints in the body are synovial joints. Synovial joints are enclosed by a ligament capsule and contain a fluid, called synovium, that lubricates the joint. The ankle syndesmosis sits next to the ankle synovial joint, where the tibia meets the talus bone.

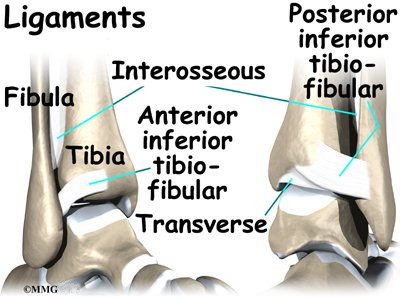

The ankle syndesmosis is supported and held together by three main ligaments. The ligament crossing just above the front of the ankle and connecting the tibia to the fibula is called the anterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (AITFL). The posterior fibular ligaments attach across the back of the tibia and fibula. These ligaments include the posterior inferior tibiofibular ligament (PITFL) and the transverse ligament.

The interosseous ligament lies between the tibia and fibula. (Interosseous means between bones.) The interosseus ligament is a long sheet of connective tissue that connects the entire length of the tibia and fibula, from the knee to the ankle.

The syndesmosis ligaments hold the bottom ends of the tibia and fibula in place. This arrangement forms the upper surface of the ankle joint. The ankle joint is a hinge joint. The hinge is formed where the tibia and fibula sit above the talus bone. This connection is called a mortise and tenon, a stable connection that woodworkers and craftsmen routinely use to create strong and stable constructions.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Ankle Anatomy

Causes

Why do I have this problem?

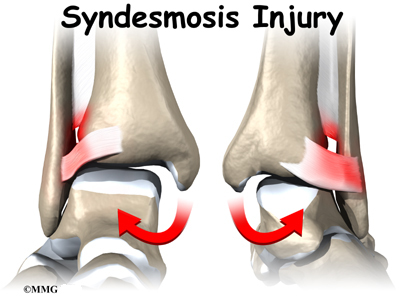

Doctors do not completely understand how syndesmosis injuries occur, though they appear to happen most often when the foot is forced upward and outward. Such injuries frequently happen in high-level football players, although snow skiers also account for a high percentage of syndesmosis injuries.

Many times, a patient describes having sprained an ankle. It isn’t until later, when standard treatments for the ankle sprain aren’t helping, that further testing shows a syndesmosis injury.

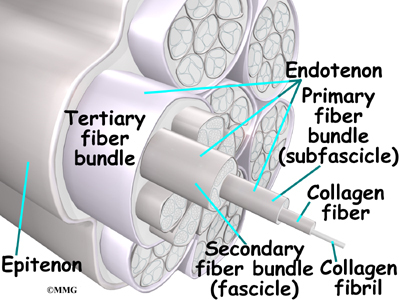

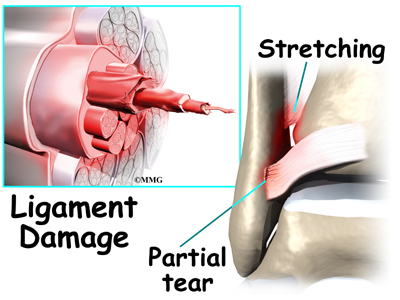

An ankle syndesmosis injury involves a sprain of one or more of the ligaments that support the ankle syndesmosis. A ligament is made up of multiple strands of connective tissue, similar to a nylon rope. A sprain stretches or tears the ligaments. Minor sprains only stretch the ligament. A tear may be either a complete tear of all the strands of the ligament or a partial tear of only some of the strands. The ligament is weakened by the injury. How much it is weakened depends on the degree of the sprain.

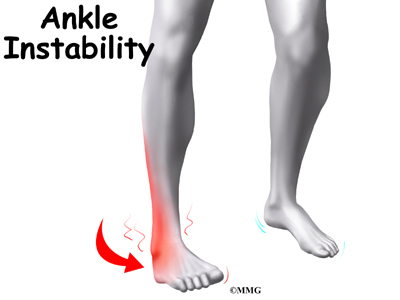

Mild syndesmosis sprains usually involve a stretch or slight tear in only one of the ligaments making up the syndesmosis. Moderate tears of the ankle syndesmosis may lead to ankle joint instability, which make the ankle mortise loose. In severe tears of the ligaments, the ends of the tibia and fibula actually spread apart. This condition is called diastasis.

Symptoms

What does an ankle syndesmosis injury feel like?

Syndesmosis injuries are the most severe sprains of the foot and ankle. They also cause the most problems for people trying to get back to normal activity, especially athletes hoping to resume intense running, cutting, and jumping.

Mild to moderate syndesmosis sprains may at first feel like a routine sprained ankle. Symptoms include pain and swelling on the outside of the ankle.

If the problem has been ongoing, patients may have pain due to an unstable ankle joint. They may feel vague pain around the ankle. Attempts to turn or twist the injured foot may cause sharp pain in the ankle joint. Pain may radiate upward along the side of the lower leg. And the ankle may feel weak, like it can’t be trusted to hold steady, even during routine activities.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Ankle Sprain and Instability

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the condition?

The diagnosis of syndesmosis injuries is usually made by examining the ankle. The doctor moves your ankle in different positions in order to check the ligaments and tendons around the ankle. The syndesmosis is stressed by turning the ankle outward while holding the lower leg still. Another test, called the squeeze test, is done by grabbing the calf just above the ankle joint and squeezing it. Pain with this test is a hallmark of a syndesmosis injury.

Tenderness can usually be pinpointed over the front ankle ligaments (the AITFL) and possibly over the posterior fibular ligaments (the PITFL and transverse ligaments).

X-rays are used to determine the severity of the syndesmosis injury. Stress X-rays are done to see if the tibia and fibula splay apart. The stress X-ray is done with the foot angled outward. An enlarged gap between the tibia and fibula indicates a diastasis (mentioned earlier). X-rays are also used to check for other problems, such as a fracture in the leg or ankle.

Doctors usually suspect a syndesmosis injury when patients have severe pain that lingers after what was thought to be a routine ankle sprain.

Treatment

What can be done for the problem?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Mild syndesmosis sprains are treated much like a regular ankle sprain. Treatment includes mild pain medications and anti-inflammatory medicine such as ibuprofin. Patients rest the ankle for a short time to reduce swelling and pain. Unlike a regular ankle sprain, doctors are much more likely to recommend using crutches to keep weight off the foot for several weeks if a syndesmosis sprain is suspected. Treatments of ice and compression (such as an elastic wrap) can help alleviate swelling and encourage a faster return of normal ankle movement. An ankle brace is worn during the rehabilitation period.

As the ankle heals, patients progress to normal walking. They also begin a series of exercises to strengthen the outer ankle muscles and to maximize balance.

Moderate syndesmosis injuries that do not show a diastasis on X-ray may be treated nonsurgically. Patients may be placed in a cast for four weeks. They use crutches to keep from putting weight on the foot during this time. After four weeks, patients are placed in a walking boot and allowed to gradually place more weight on their foot over another three to four weeks. X-rays are usually taken every two weeks to make sure the ankle mortise isn’t separating. Treatment gradually intensifies over a three-month period.

Surgery

Syndesmosis injuries that cause ankle instability may require surgery. Some doctors prefer to try nonsurgical treatment first. However, if at any point during treatment an X-ray shows a diastasis, surgery will probably be recommended.

Screw Fixation

Surgery for a syndesmosis injury is designed to reduce the separation between the tibia and fibula. If there are no barriers keeping the tibia and fibula apart, the surgeon may simply need to place screws through the two bones to hold them together while the ligaments heal.

To begin the procedure, the surgeon bends the ankle slightly upward. A clamp may be placed around the lower leg to squeeze the tibia and fibula together, reducing the separation. This places the two bones in the proper alignment.

Working from the outer side of the leg, the surgeon inserts a screw through fibula into the tibia. This is done with the aid of a fluoroscope. A fluoroscope is a special X-ray machine that allows the surgeon to see the live X-ray picture on a TV screen during surgery. Using the fluoroscope allows the surgeon to direct the drill and place the screws into the right spot to hold the bones in the right position. This can usually be done through small, quarter-inch incisions in the side of the ankle. Some surgeons place a second screw right above the first screw.

Surgeons generally use a screw with a large head. This ensures easy removal of the screw after two or three months.

Open Incision

If the tibia and fibula can’t be squeezed together, the surgeon may have to make an incision on the front edge of the ankle. This allows the surgeon to find and remove any scar tissue or other barriers that are keeping the bones apart.

In both procedures, X-rays of both ankles are taken after the screws are in place. Comparing the X-rays lets the surgeon see if the space between the tibia and fibula is now the same on both sides.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect following treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Even if you don’t need surgery, you may need to follow a program of rehabilitation exercises. Your doctor may recommend that you work with a physical therapist. Your therapist can create a program to help you regain ankle function. It is very important to improve strength and coordination in the ankle. It is vital to remember that an ankle syndesmosis injury is more complex than a simple ankle sprain. The healing time is at least twice as long, and getting back to normal activity is usually a more gradual process.

After Surgery

For two to four weeks after surgery, patients usually wear an ankle splint and avoid placing weight down when standing or walking. Then a stirrup brace is worn as the amount of weight put on the foot is gradually increased. Rehabilitation after surgery can be a slow process. You will probably need to attend therapy sessions for two to three months, and you should expect full recovery to take up to six months.

The first few physical therapy treatments are designed to help control pain and swelling from the surgery. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may be used during your first few therapy sessions. Your therapist may also use massage and other hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain. Treatments are also used to help improve ankle range of motion without putting too much strain on the ankle.

Gentle ankle movements can begin after two to four weeks. You may begin easy ankle motions on a stationary bicycle. After about six weeks you may start doing more active exercise. Exercises are used to improve the strength in the ankle muscles. Your therapist will also help you regain position sense in the ankle joint to improve its stability. A careful progression to running and other impact activities begins a minimum of 12 weeks after surgery.

The physical therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control, improve your range of motion, and maximize strength and control in your ankle. When you are well under way, regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.