A Patient’s Guide to Osteonecrosis of the Humeral Head

Introduction

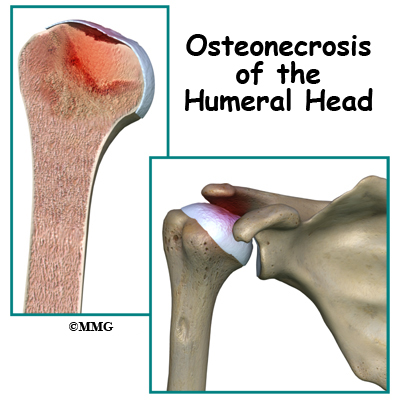

Osteonecrosis of the humeral head is a condition where a portion of the bone of the humeral head (the top of the humerus or upper arm bone) loses its blood supply, dies and collapses. Another term used for osteonecrosis is avascular necrosis. The term avascular means that a loss of blood supply to the area is the cause of the problem and necrosis means death.

This condition has been reported in all age groups but seems more common between the ages of 20 and 50. Men are affected by osteonecrosis of the shoulder twice as often as women but women with osteonecrosis from an autoimmune disease (e.g., lupus) develop this condition more often than men with the same disease.

This guide will help you understand

- how osteonecrosis develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

Where does this condition occur?

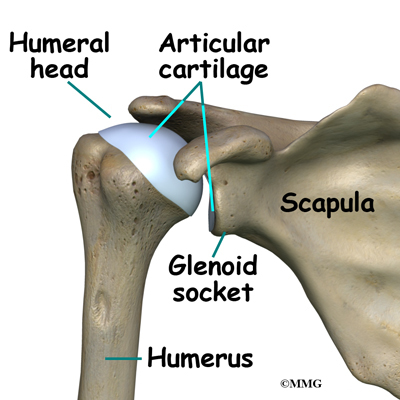

The shoulder joint is a ball-and-socket joint. The ball portion of the joint is called the humeral head. The humeral head is the uppermost part of the humerus, or upper arm bone. The shoulder socket is called the glenoid fossa. This socket is shallow and is part of the scapula (shoulder blade). The surface of the humeral head and the inside of the fossa are covered with articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is a tough, slick material that allows the surfaces to slide against one another with very little friction. The cartilage is about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large weight-bearing joints, but a bit thinner in the shoulder, which normally doesn’t support much weight.

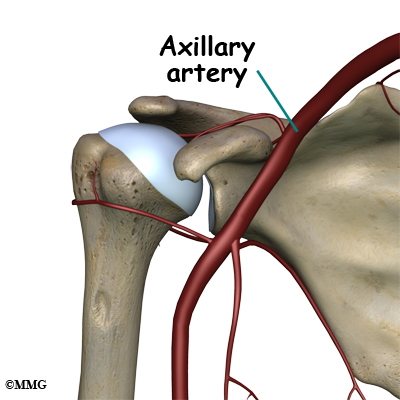

Large blood vessels supply the arm with blood. The large axillary artery travels through the axilla (armpit). If you place your hand in your armpit, you may be able to feel the pulsing of this large artery. The axillary artery has many smaller branches that supply blood to different parts of the shoulder. The shoulder has a very rich blood supply. But if this blood supply is damaged, there is no backup.

Causes

What causes this condition?

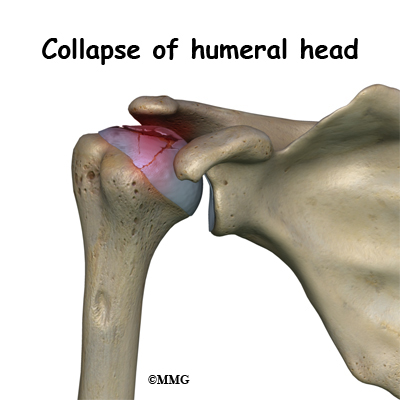

When osteonecrosis occurs in the shoulder joint, the top of the humeral head (the ball portion) collapses and begins to flatten. The flattening creates a situation where the ball no longer fits perfectly inside the socket. Like two pieces of a mismatched piece of machinery, the joint begins to wear itself out. This leads to osteoarthritis of the joint and pain.

Bone tissue is constantly being remodeled – old bone is removed and replaced with new bone. Osteonecrosis occurs when there is a loss of blood circulation in the bone of the humeral head. This causes the cells that remove and produce new bone to die in the area of lost circulation. New bone is no longer produced, but the old bone matrix still survives. Without the constant ability to repair itself through remodeling, the dead bone matrix eventually begins to lose strength and crumble. This causes the bone matrix to collapse. New blood vessels begin to grow into the area, but this is a slow process. The situation becomes a race to see whether new blood vessels will grow into the area and restore the ability to remodel the bone or whether collapse will occur.

The articular cartilage on the surface of the humeral head does not rely on the blood supply of the bone to survive. The articular surface is nourished by the synovial fluid; it survives the loss of blood flow to the bone. But, the articular cartilage relies on the bone underneath to keep its round shape. When the bone underneath collapses, the articular cartilage loses its round shape and no longer fits, or matches, the shape of the glenoid socket. The constant abnormal friction between the two mismatched joint surfaces causes mechanical wear and tear in both the humeral head and the glenoid socket. This degeneration is called osteoarthritis.

There are two forms of humeral head osteonecrosis: traumatic and atraumatic. The traumatic type can develop after an injury such as a bone fracture or shoulder dislocation. The nontraumatic form occurs with the use of corticosteroids, or it can be associated with other diseases or blood disorders (e.g., sickle cell disease, problems with coagulation or making blood clots). Sometimes it develops with no known cause. In those cases, it is called idiopathic (unknown cause).

There does seem to be a genetic link but exposure to certain risk factors is also part of the picture. For example, alcohol abuse, tobacco use, chemotherapy, radiation, pregnancy, inflammatory bowel disease, and organ transplantation are considered associated risk factors. A clear link exists between osteonecrosis and alcoholism. Excessive alcohol intake somehow damages the blood vessels and leads to osteonecrosis. Organ recipients must be on lifelong steroids to prevent inflammation, infection, and rejection of the organ. These medications have the adverse side effect of endangering blood supply and weakening the bone.

Symptoms

What does osteonecrosis feel like?

The first symptom of osteonecrosis of the humeral head is shoulder and arm pain. The location of the pain is difficult to isolate. You may not be able to point to it with one finger. You may feel like the pain is deep and throbbing. You may have difficulty reaching your arms out to the sides or overhead.

At first, the symptoms seem to come and go, but as the problem progresses (gets worse), the symptoms become more constant and stiffness develops in the shoulder joint. Pain may radiate, or travel, from your shoulder down to your elbow. There may be a sound and sensation of crunching called crepitus and locking in the joint. With arthritic changes, range of motion decreases. Eventually, the pain will also be present at rest and may even interfere with sleep. In a small number of cases, there are no symptoms despite X-rays that show advanced disease.

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose this condition??

Your doctor will conduct a thorough history and carry out a clinical exam. The history helps identify associated risk factors, which will have to be addressed during treatment in order to get the most successful results. Your doctor will also check other joints for any signs of similar problems. In about half the patients, osteonecrosis is also present at the hip, knee, ankle, wrist, and/or elbow.

Lab studies can be done to rule out infection or test for systemic diseases or blood disorders that can cause osteonecrosis.

Standard X-rays are usually ordered to confirm the diagnosis. Several different views are needed. Besides the usual anterior-posterior (AP) views, radiographs should include views with the joint in external (outward) and internal (inward) rotation. That will help show all areas of the diseased humeral head, important information for planning treatment.

X-rays don’t always show all of the changes until the condition has been present for quite some time. MRIs may be used to define more clearly early changes in fat and water content of the bone marrow that won’t be seen on X-ray. Bone scans have fallen out of favor for the detection and diagnosis of osteonecrosis. Studies show only one-third of true cases are successfully identified with this imaging tool.

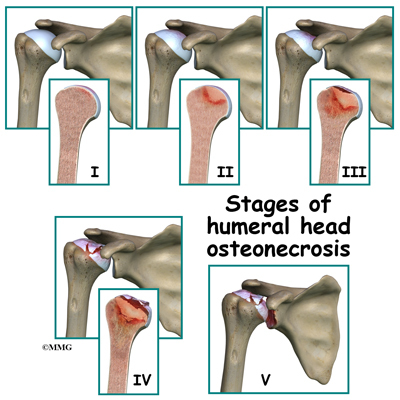

Treatment is based on the severity of disease, so part of the diagnosis is to identify what stage the disease is in. The stages start with stage I, which means no changes are seen on X-ray images and go up to stage V. In stage V (the most advanced disease) the humeral head is collapsed and the socket is damaged as well. There may be soft tissue tears present in the more advanced stages.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

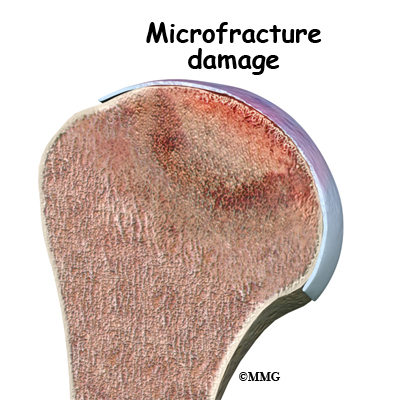

The first goal in treating osteonecrosis of the humeral head is to save the bone. Left untreated, the disease process will continue until the layer of bone just under the joint surface cracks causing small microfractures. Once enough microfactures happen, the bone begins to collapse and the articular cartilage covering the joint surface also starts to collapse. Eventually, there will be damage to the entire shoulder joint. The second goal is to keep shoulder function while relieving pain. Various nonsurgical and surgical methods have been used to treat this problem.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The first line of treatment is medication to restore blood supply and allow new bone growth. Some of the more common drugs used include lipid-lowering (cholesterol-lowering) agents, vasodilators (opens up the blood vessels), anticoagulants (prevents blood clotting), and bisphosphonates (prevents bone loss). The type of medication used depends on the underlying systemic disease causing the bone problem. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may provide some symptom relief of the osteoarthritis but they do not slow or stop the osteonecrosis.

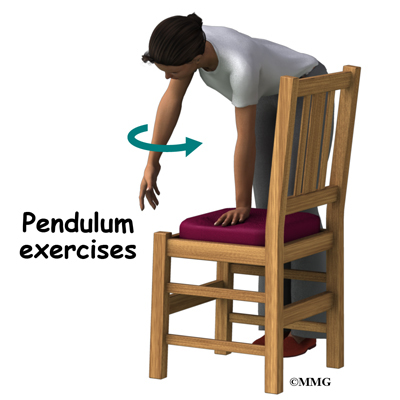

Depending on your symptoms and limitations in motion and strength, you may be started on a series of exercises called pendulum exercises. These are designed to help keep full motion in the shoulder joint but without stressing the joint. You may be told to avoid lifting your arm overhead or away from the body against resistance. You should also avoid lifting or holding anything heavy. Your doctor may give you a weight restriction (i.e., don’t lift anything more than two to five pounds). Putting away heavy groceries for example should be avoided at this time.

Physical therapy that include modalities for pain control and progression of range-of-motion exercises with subsequent strengthening is helpful in all stages, particularly in stage I and stage II.

Patients are advised to stop using tobacco or alcohol. Anyone taking corticosteroids should consult with the prescribing physician to review the need for and use of these medications because of their possible adverse effect on bone.

Surgery

Core Decompression

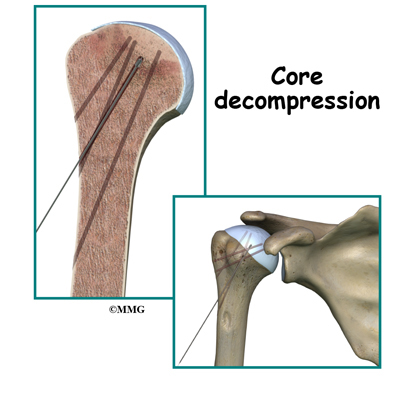

Surgical intervention may be needed in the more advanced stages of osteonecrosis. When the condition is in the early stages, a procedure called core decompression is used to reduce bone marrow pressure and allow the formation of new blood supply to the area. The new blood vessels help the necrotic area start to form new, healthy bone.

Core decompression is done by drilling small holes from the healthy bone to the area of necrosis in the humeral head. This creates channels that allow new blood vessels to grow into the necrotic area. The surgeon uses a special type of X-ray called fluoroscopy to guide the placement of the pins used to drill the holes. Removing some of the dead bone also causes bleeding into the region of necrotic bone and stimulates new bone growth.

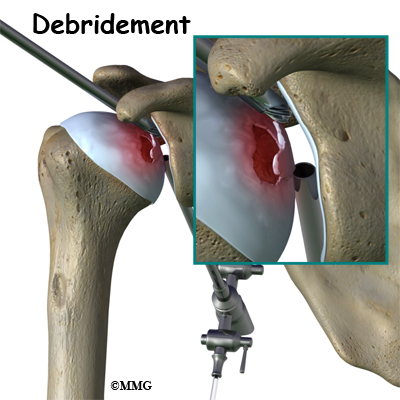

Arthroscopy

If there are any loose bits of bone or cartilage in the joint, then the surgeon may have to perform arthroscopic debridement . The arthroscope is a small fiberoptic camera that can be inserted into the joint allowing the surgeon to see the inside of the joint. Other instruments can be inserted into the joint though small incisions to remove tissue and smooth the surface of the joint. The shoulder joint is cleaned up of any debris. Any frayed edges of joint cartilage are smoothed down. Sometimes the surgeon combines these two procedures (decompression and arthroscopy). The arthroscopic exam shows the location and extent of the disease in the joint while the decompression addresses the necrotic area of bone.

Bone Grafting

Bone grafting replaces the necrotic (dead) bone with donor bone that is usually taken from the patient’s own hip. This treatment approach is used for mild to moderate disease. It is not advised for late stage disease as studies show patients with more advanced disease do better with arthroplasty (joint replacement). The bone graft gives the joint surface support needed to keep it from collapsing. With that support in place, the bone can begin to heal.

Arthroplasty

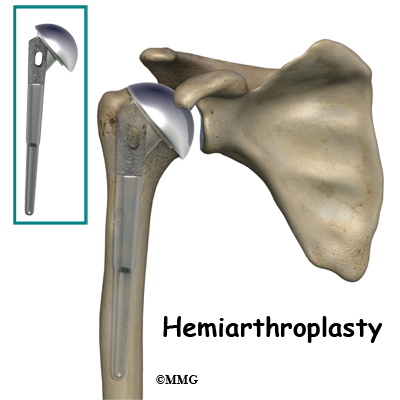

Joint replacement is used for more severe damage of the the joint. A hemiarthroplasty (partial replacement) may be all that’s needed when only one side of the joint has been affected. Full joint replacement is reserved for patients with significant involvement of both the humeral head and the glenoid fossa (socket).

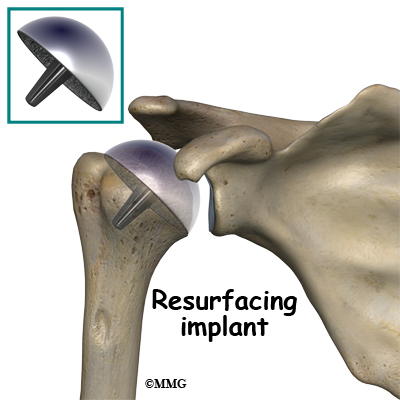

A newer procedure called humeral head resurfacing is gaining popularity and may help save the joint. Instead of removing the head of the humerus and replacing it, the bone is smoothed down and a metal cap placed over the smoothed head like a tooth capped by the dentist. The cap is held in place with a small peg that fits down into the bone. Joint resurfacing requires that the patient have enough healthy bone to support the cap.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

Studies show that the results of nonsurgical treatment are satisfactory when the disease is caught during the early stages. Symptoms often remain mild, even when the disease is advanced. Since the shoulder does not involve weight-bearing like the hip, good results are obtained with conservative care. Physical therapy may be needed for extended periods of time. There are some patients who will continue to progress despite early conservative care. Predicting who might develop more advanced disease is difficult, so close monitoring is advised.

After Surgery

After core decompression, you may be wearing a sling for a few days. Many patients report immediate pain relief. Active-assisted motion is allowed in all directions. Active-assisted means you use your other hand (or hold a cane or some other type of stick with both hands) to help guide the involved side through the motion. Movements are not forced. You’ll go as far as you can comfortably.

You will gradually resume all normal activities over a period of four or five weeks — as long as you remain pain free. High-impact activities or activities that load the joint are not allowed for a full year following decompression.

With any of the more invasive procedures such as joint replacement, passive range-of-motion is carried out under the supervision of a physical therapist. Because major muscles are cut and reattached during the operation, regaining motion is progressed slowly to protect the healing soft tissues.

Active motion (moving under your own muscle power without help) is not allowed for the first three weeks. In fact, the therapist will move you from passive motion through active-assistive motion and then to active motion over a period of six weeks. Stretching and strengthening don’t begin until around week 12 post-op.

Results of treatment are often good but patients should be prepared for the possibility that the condition can progress over time. Further surgery may be needed. For those who have decompression or bone grafting, joint replacement may be needed eventually.