A Patient’s Guide to Iliotibial Band Syndrome

Introduction

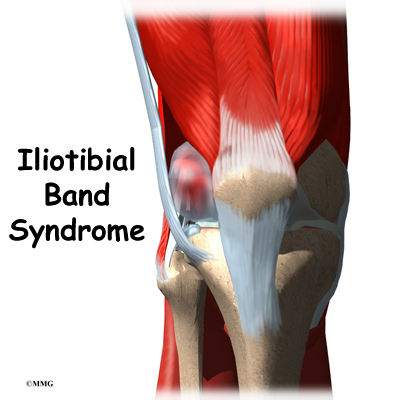

Iliotibial band (ITB) syndrome is an overuse problem that is often seen in bicyclists, runners, and long-distance walkers. It causes pain on the outside of the knee just above the joint. It rarely gets so bad that it requires surgery, but it can be very bothersome. The discomfort may keep athletes and other active people from participating in the activities they enjoy.

This guide will help you understand

- how ITB syndrome develops

- how the condition causes problems

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What is the ITB, and what does it do?

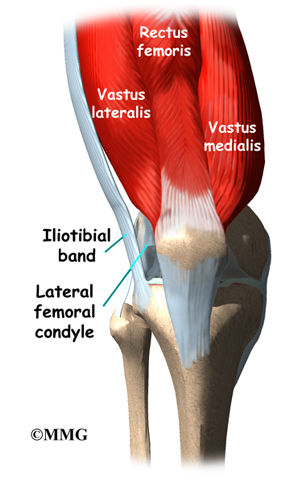

The ITB is actually a long tendon. (Tendons connect muscles to bone.) It attaches to a short muscle at the top of the pelvis called the tensor fascia lata. The ITB runs down the side of the thigh and connects to the outside edge of the tibia (shinbone) just below the middle of the knee joint. You can feel the tendon on the outside of your thigh when you tighten your leg muscles. The ITB crosses over the side of the knee joint, giving added stability to the knee.

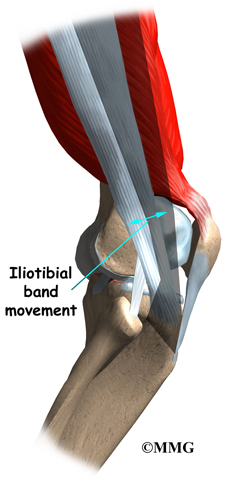

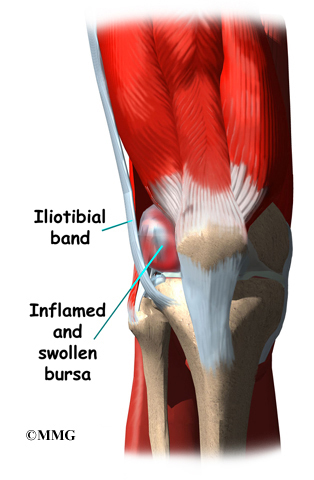

The lower end of the ITB passes over the outer edge of the lateral femoral condyle, the area where the lower part of the femur (thighbone) bulges out above the knee joint. When the knee is bent and straightened, the tendon glides across the edge of the femoral condyle.

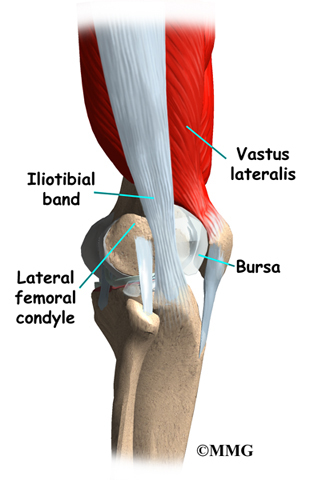

A bursa is a fluid-filled sac that cushions body tissues from friction. These sacs are present where muscles or tendons glide against one another. A bursa rests between the femoral condyle and the ITB. Normally, this bursa lets the tendon glide smoothly back and forth over the edge of the femoral condyle as the knee bends and straightens.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Knee Anatomy

Causes

How does ITB syndrome develop?

The ITB glides back and forth over the lateral femoral condyle as the knee bends and straightens. Normally, this isn’t a problem. But the bursa between the lateral femoral condyle and the ITB can become irritated and inflamed if the ITB starts to snap over the condyle with repeated knee motions such as those from walking, running, or biking.

People often end up with ITB syndrome from overdoing their activity. They try to push themselves too far, too fast, and they end up running, walking, or biking more than their body can handle. The repeated strain causes the bursa on the side of the knee to become inflamed.

Some experts believe that the problem happens when the knee bows outward. This can happen in runners if their shoes are worn on the outside edge, or if they run on slanted terrain. Others feel that certain foot abnormalities, such as foot pronation, cause ITB syndrome. (Pronation of the foot occurs when the arch flattens.)

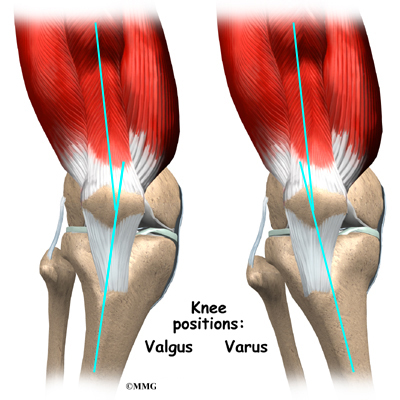

Recently, health experts have found that runners with a weakened or fatigued gluteus medius muscle in the hip are more likely to end up with ITB syndrome. This muscle controls outward movements of the hip. If the gluteus medius isn’t doing its job, the thigh tends to turn inward. This makes the knee angle into a knock-kneed position. The ITB becomes tightened against the bursa on the side of the knee. This is also called a valgus deformity of the knee.

People with bowed legs may also be at risk of developing ITB syndrome. The outward angle of the bowed knee makes the lateral femoral condyle more prominent and can make the snapping worse. This condition is also called a varus deformity of the knee.

Symptoms

What does ITB syndrome feel like?

The symptoms of ITB syndrome commonly begin with pain over the outside of the knee, just above the knee joint. Tenderness in this area is usually worse after activity. As the bursitis grows worse, pain may radiate up the side of the thigh and down the side of the leg. Patients sometimes report a snapping or popping sensation on the outside of the knee.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor know it’s ITB syndrome?

The diagnosis of ITB syndrome can usually be made without any complicated tests. Your doctor will take a history of the problem and ask about any other injuries that may have occurred in the past. X-rays may be taken to make sure that there are no other injuries that could be adding to the problem. Generally, no swelling is visible. The snapping sensation usually cannot be heard.

Pain on the outside of the knee can be caused from conditions other than ITB syndrome. Your doctor will perform an examination of the knee and will look at your entire leg. You may want to take the shoes that you use to run or walk with you to your appointment.

If there is doubt about the diagnosis, or you are still having problems after reasonable attempts have been made to decrease the symptoms, a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan may be suggested by your doctor. An MRI scan is a special test that uses magnetic waves to create images of the soft tissues inside and around the knee. Regular X-rays only show the bones around the knee. The MRI can show if there are problems with the soft tissues such as the cartilage and ligaments.

Treatment

What can be done for the condition?

Nonsurgical Treatment

Most cases of ITB syndrome can be treated with simple measures. At first, heat, ice, and ultrasound may be used to help calm pain and inflammation.

Your doctor may prescribe physical therapy, where the problems that are causing your symptoms will be evaluated and treated. Stretching and strengthening exercises may be used in combination with a knee brace, kneecap taping, or shoe inserts to improve muscle balance and joint alignment of the hip and lower limb. Your physical therapist will probably ask you about your sport activities and may give you tips on your warm up and training schedule, footwear, and choices of terrain.

If your symptoms continue, your doctor may suggest an injection of cortisone into the bursa. Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication that may help reduce the inflammation and take away the pain.

Surgery

Surgery is rarely needed to correct ITB problems. Surgery consists of removing the bursa and releasing, or lengthening, the ITB just enough so that the friction is reduced when the knee is bent and straightened.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

If your treatment is nonsurgical, you should be able to return to normal activity within four to six weeks. You may work with a physical therapist during this time. A key element of treatment is your training schedule. Your therapist can work with you to adjust the distance you run, your footwear, and the running surfaces you choose.

Foot orthotics may be recommended to improve foot and lower limb alignment. Wearing orthotics in your shoes may allow you to resume normal walking immediately, but you should probably cut back on more vigorous activities for several weeks to allow the inflammation and pain to subside.

Strengthening and stretching exercises are chosen to correct muscle imbalances, such as weakness in the gluteus medius muscle or tightness in the ITB.

Treatments such as ultrasound, friction massage, and ice may be used to calm inflammation in the ITB. Therapy sessions sometimes include iontophoresis, which uses a mild electrical current to push anti-inflammatory medicine to the sore area. This treatment is especially helpful for patients who can’t tolerate injections.

After Surgery

If you’ve undergone surgery, you and your surgeon will need to come up with a plan for your rehabilitation. You will have a period of rest, which may involve using crutches. You will also need to start a careful and gradual exercise program. Patients often work with physical therapists to direct the exercises for their rehabilitation program.

The therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control, improve muscle and joint alignment, and return you to your sport or activity without additional problems. When you are well under way, regular visits to your therapist’s office will end. The therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.