A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Hip

Introduction

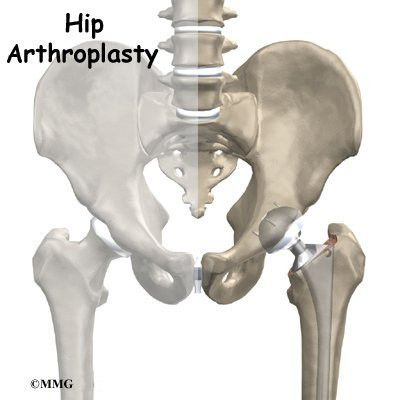

A hip that is painful as a result of osteoarthritis (OA) can severely affect your ability to lead a full, active life. Over the last 25 years, major advancements in hip replacement have improved the outcome of the surgery greatly. Hip replacement surgery (also called hip arthroplasty) is becoming more and more common as the population of the world begins to age.

This guide will help you understand

- what your surgeon hopes to achieve

- what happens during the procedure

- what to expect after your operation

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Osteoarthritis of the Hip

Anatomy

How does the hip normally work?

The hip joint is one of the true ball-and-socket joints of the body. The hip socket is called the acetabulum and forms a deep cup that surrounds the ball of the upper thigh bone, known as the femoral head. The thick muscles of the buttock at the back and the thick muscles of the thigh in the front surround the hip.

The surface of the femoral head and the inside of the acetabulum are covered with articular cartilage. This material is about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large joints. Articular cartilage is a tough, slick material that allows the surfaces to slide against one another without damage.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hip Anatomy

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to achieve?

The main reason for replacing any arthritic joint with an artificial joint is to stop the bones from rubbing against each other. This rubbing causes pain. Replacing the painful and arthritic joint with an artificial joint gives the joint a new surface, which moves smoothly without causing pain. The goal is to help people return to many of their activities with less pain and greater freedom of movement.

Preparation

How should I prepare for surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery should be made jointly by you and your surgeon only after you feel that you understand as much about the procedure as possible.

Once the decision to proceed with surgery is made, several things may need to be done. Your orthopedic surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your medical or family doctor. This is to ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation. You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after the surgery.

One purpose of the preoperative physical therapy visit is to record a baseline of information. This includes measurements of your current pain levels, functional abilities, and the movement and strength of each hip.

A second purpose of the preoperative therapy visit is to prepare you for your upcoming surgery. You will begin to practice some of the exercises you will use just after surgery. You will also be trained in the use of either a walker or crutches. Whether the surgeon uses a cemented or noncemented approach may determine how much weight you will be able to apply through your foot while walking.

This procedure requires the surgeon to open up the hip joint during surgery. This puts the hip at some risk for dislocation after surgery. To prevent dislocation, patients follow strict guidelines about which hip positions to avoid (called hip precautions). Your therapist will review these precautions with you during the preoperative visit and will drill you often to make sure you practice them at all times for at least six weeks. Some surgeons give the OK to discontinue the precautions after six to 12 weeks because they feel the soft tissues have gained enough strength by this time to keep the joint from dislocating.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Hip Dislocation Precautions

Finally, the therapist assesses any needs you will have at home once you’re released from the hospital.

You may be asked to donate some of your own blood before the operation. This blood can be donated three to five weeks before the operation, and your body will make new blood cells to replace the loss. At the time of the operation, if you need to have a blood transfusion you will receive your own blood back from the blood bank.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during the operation?

Before we describe the procedure, let’s look first at the artificial hip itself.

The Artificial Hip

There are two major types of artificial hip replacements:

- cemented prosthesis

- uncemented prosthesis

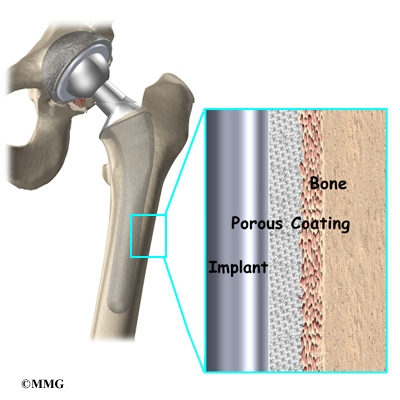

A cemented prosthesis is held in place by a type of epoxy cement that attaches the metal to the bone. An uncemented prosthesis bears a fine mesh of holes on the surface that allows bone to grow into the mesh and attach the prosthesis to the bone.

Both are still widely used. In some cases a combination of the two types is used in which the ball portion of the prosthesis is cemented into place, and the socket not cemented. The decision about whether to use a cemented or uncemented artificial hip is usually made by the surgeon based on your age and lifestyle, and the surgeon’s experience.

Each prosthesis is made of two main parts. The acetabular component (socket) replaces the acetabulum. The acetabular component is made of a metal shell with a plastic inner liner that provides the bearing surface.

The plastic used is so tough and slick that you could ice skate on a sheet of it without much damage to the material.

The femoral component (stem and ball) replaces the femoral head. The femoral component is made of metal. Sometimes, the metal stem is attached to a ceramic ball.

The Operation

The surgeon begins by making an incision on the side of the thigh to allow access to the hip joint. Several different approaches can be used to make the incision. The choice is usually based on the surgeon’s training and preferences.

Once the hip joint is entered, the surgeon dislocates the femoral head from the acetabulum. Then the femoral head is removed by cutting through the femoral neck with a power saw. Attention is then turned toward the socket. The surgeon uses a power drill and a special reamer (a cutting tool used to enlarge or shape a hole) to remove cartilage from inside the acetabulum. The surgeon shapes the socket into the form of a half-sphere. This is done to make sure the metal shell of the acetabular component will fit perfectly inside. After shaping the acetabulum, the surgeon tests the new component to make sure it fits just right.

In the uncemented variety of artificial hip replacement, the metal shell is held in place by the tightness of the fit or by using screws to hold the shell in place. In the cemented variety, a special epoxy-type cement is used to anchor the acetabular component to the bone.

To begin replacing the femur, special rasps (filing tools) are used to shape the hollow femur to the exact shape of the metal stem of the femoral component. Once the size and shape are satisfactory, the stem is inserted into the femoral canal.

Again, in the uncemented variety of femoral component the stem is held in place by the tightness of the fit into the bone (similar to the friction that holds a nail driven into a hole that is slightly smaller than the diameter of the nail). In the cemented variety, the femoral canal is enlarged to a size slightly larger than the femoral stem, and the epoxy-type cement is used to bond the metal stem to the bone.

The metal ball that makes up the femoral head is then inserted.

Once the surgeon is satisfied that everything fits properly, the incision is closed with stitches. Several layers of stitches are used under the skin, and either stitches or metal staples are then used to close the skin. A bandage is applied to the incision, and you are returned to the recovery room.

View animation of removing the femoral head

View animation of reaming the acetabulum

View animation of testing the new acetabular component

View animation of shaping the femur

View animation of inserting the stem

View animation of inserting the metal ball

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following hip replacement surgery include

- anesthesia complications

- thrombophlebitis

- infection

- dislocation

- loosening

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

View animation of Pulmonary Embolism

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but it is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when the blood in the large veins of the leg forms blood clots. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Infection can be a very serious complication following artificial joint replacement surgery. The chance of getting an infection following total hip replacement is probably around one percent. Some infections may show up very early, even before you leave the hospital. Others may not become apparent for months, or even years, after the operation. Infection can spread into the artificial joint from other infected areas. Your surgeon may want to make sure that you take antibiotics when you have dental work or surgical procedures on your bladder or colon to reduce the risk of spreading germs to the joint.

Dislocation

Just like your real hip, an artificial hip can dislocate if the ball comes out of the socket. There is a greater risk just after surgery, before the tissues have healed around the new joint, but there is always a risk. The physical therapist will instruct you very carefully how to avoid activities and positions which may have a tendency to cause a hip dislocation. A hip that dislocates more than once may have to be revised to make it more stable. This means another operation.

Loosening

The main reason that artificial joints eventually fail continues to be the loosening of the metal or cement from the bone. Great advances have been made in extending how long an artificial joint will last, but most will eventually loosen and require a revision. Hopefully, you can expect 12 to 15 years of service from an artificial hip, but in some cases the hip will loosen earlier than that. A loose hip is a problem because it causes pain. Once the pain becomes unbearable, another operation will probably be required to revise the hip.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Revision Arthroplasty of the Hip

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

After surgery, your hip will be covered with a padded dressing. Special boots or stockings are placed on your feet to help prevent blood clots from forming. A triangle-shaped cushion may be positioned between your legs to keep your legs from crossing or rolling in.

If your surgeon used a general anesthesia, a nurse or respiratory therapist will visit your room to guide you in a series of breathing exercises. You’ll use an incentive spirometer to improve breathing and avoid possible problems with pneumonia.

Physical therapy treatments are scheduled one to three times each day as long as you are in the hospital. Your first treatment is scheduled soon after you wake up from surgery. Your therapist will begin by helping you move from your hospital bed to a chair. By the second day, you’ll begin walking longer distances using your crutches or walker. Most patients are safe to put comfortable weight down when standing or walking. However, if your surgeon used a noncemented prosthesis, you may be instructed to limit the weight you bear on your foot when you are up and walking.

Your therapist will review exercises to begin toning and strengthening the thigh and hip muscles. Ankle and knee movements are used to help pump swelling out of the leg and to prevent the formation of blood clots.

Patients are usually able to go home after spending four to seven days in the hospital. You’ll be on your way home when you can demonstrate a safe ability to get in and out of bed, walk up to 75 feet with your crutches or walker, go up and down stairs safely. and consistently remember to use your hip precautions. Patients who still need extra care may be sent to a different hospital unit until they are safe and ready to go home.

Most orthopedic surgeons recommend that you have checkups on a routine basis after your artificial joint replacement. How often you need to be seen varies from every six months to every five years, according to your situation and what your surgeon recommends.

Patients who have an artificial joint will sometimes have episodes of pain, but if you have a period that lasts longer than a couple of weeks you should consult your surgeon. During the examination, the orthopedic surgeon will try to determine why you are feeling pain. X-rays may be taken of your artificial joint to compare with the ones taken earlier to see whether the joint shows any evidence of loosening.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect during my recovery?

After you are discharged from the hospital, your therapist may see you for one to six in-home treatments. This is to ensure you are safe in and about the home and getting in and out of a car. Your therapist will review your exercise program, continue working with you on your hip precautions, and make recommendations about your safety.

These safety tips include using raised commode seats and bathtub benches, and raising the surfaces of couches and chairs. This keeps your hip from bending too far when you sit down. Bath benches and handrails can improve safety in the bathroom. Other suggestions may include the use of strategic lighting and the removal of loose rugs or electrical cords from the floor.

You should use your walker or crutches as instructed. If you had a cemented procedure, you’ll advance the weight you place through your sore leg as much as you feel comfortable. If you had a noncemented procedure, your surgeon may want you to place only the toes of your operated leg down for up to six weeks after surgery. Most patients progress to using a cane in three to four weeks.

Your staples will be removed two weeks after surgery. Patients are usually able to drive within three weeks and walk without a walking aid by six weeks. Upon the approval of the surgeon, patients are generally able to resume sexual activity by one to two months after surgery.

Home therapy visits end when you are safe to get out of the house, which may take up to three weeks.

The need for physical therapy usually ends when home care is completed. But a few additional visits in outpatient physical therapy may be needed for patients who have problems walking or who need to get back to heavier types of work or activities.

Your therapist may use heat, ice, or electrical stimulation to reduce any swelling or pain.

Therapists sometimes treat their patients in a pool. Exercising in a swimming pool puts less stress on the hip joint, and the buoyancy lets you move and exercise easier. Once you’ve gotten your pool exercises down and the other parts of your rehab program advance, you may be instructed in an independent program.

When you are safe in putting full weight through the leg, several types of balance exercises can be chosen to further stabilize and control the hip.

Finally, a select group of exercises can be used to simulate day-to-day activities, such as going up and down steps, squatting, and walking on uneven terrain. Specific exercises may then be chosen to simulate work or hobby demands.

Many patients have less pain and better mobility after having hip replacement surgery. Your therapist will work with you to help keep your new joint healthy for as long as possible. This may require that you adjust your activity choices to keep from putting too much strain on your new hip joint. Heavy sports that require running, jumping, quick stopping and starting, and cutting are discouraged. Patients may need to consider alternate jobs to avoid work activities that require heavy demands of lifting, crawling, and climbing.

The therapist’s goal is to help you maximize strength, walk normally, and improve your ability to do your activities. When you are well under way, regular visits to the therapist’s office will end. Your therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.