A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Shoulder

Introduction

Shoulder joint replacement surgery (also called shoulder arthroplasty) is not as common as replacement surgeries for the knee or hip joints. Still, when necessary, this operation can effectively ease pain from shoulder arthritis. Most people experience improved shoulder function after this surgery.

This guide will help you understand

- how the shoulder works

- what parts of the shoulder are replaced in surgery

- what to expect after shoulder replacement surgery

Anatomy

What parts make up the shoulder?

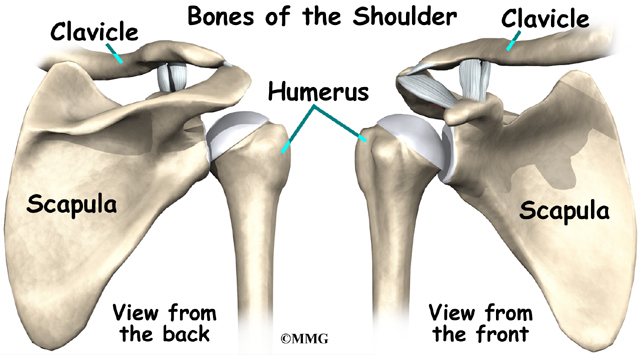

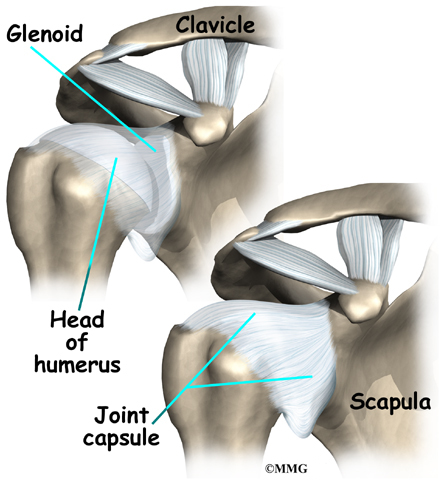

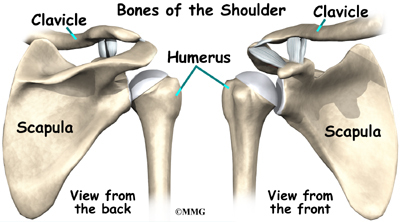

The shoulder is made up of three bones: the scapula (shoulder blade), the humerus (upper arm bone), and the clavicle (collarbone).

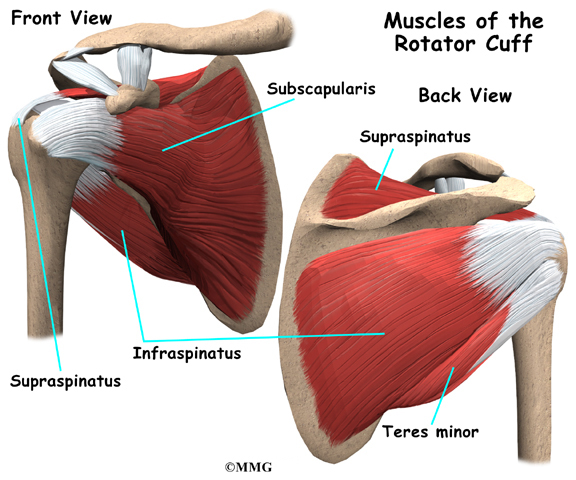

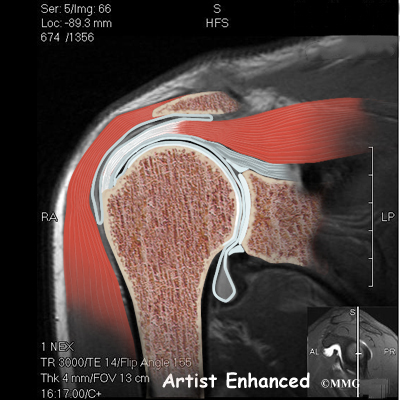

The rotator cuff connects the humerus to the scapula. The rotator cuff is formed by the tendons of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor, and subscapularis.

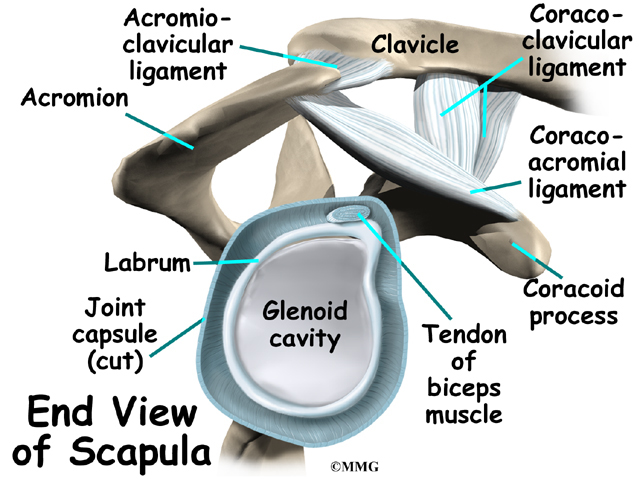

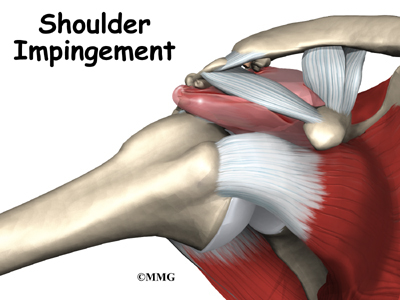

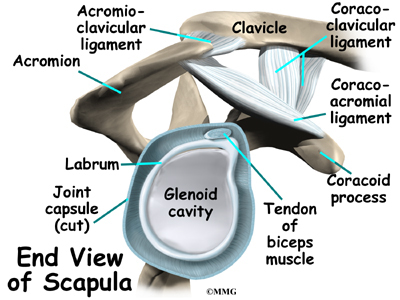

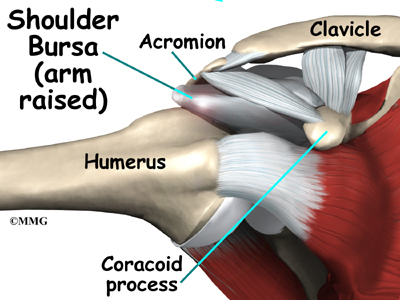

Tendons attach muscles to bones. Muscles move bones by pulling on the tendons. The rotator cuff helps raise and rotate the arm. As the arm is raised, the rotator cuff also keeps the humerus tightly in the socket. A part of the scapula, called the glenoid, makes up the socket of the shoulder. The glenoid is very shallow and flat.

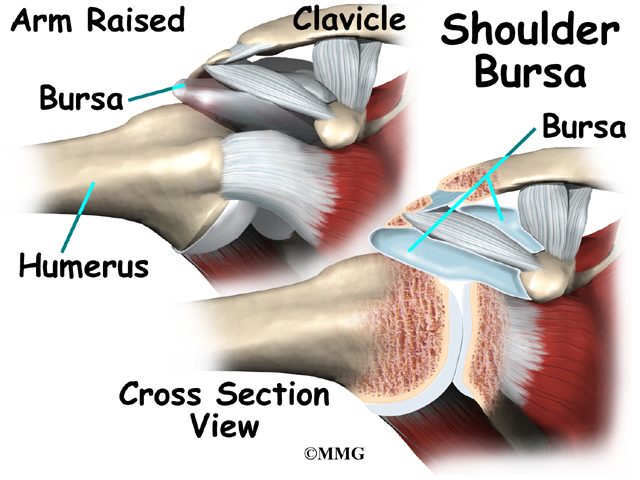

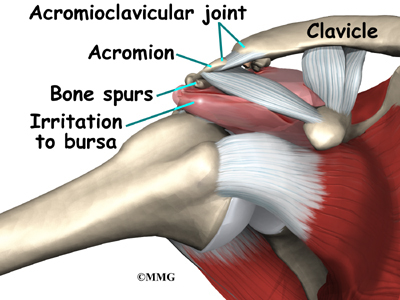

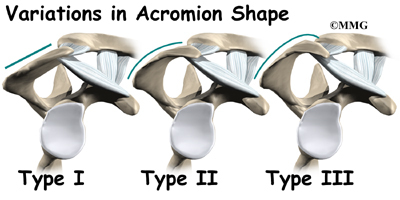

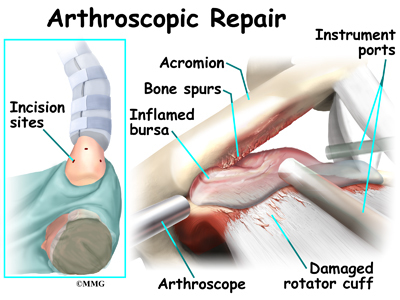

The part of the scapula that connects to the shoulder is called the acromion. A bursa is located between the acromion and the rotator cuff tendons. A bursa is a lubricated sac of tissue that cuts down on the friction between two moving parts. Bursae are located all over the body where tissues must rub against each other. In this case, the bursa protects the acromion and the rotator cuff from grinding against each other.

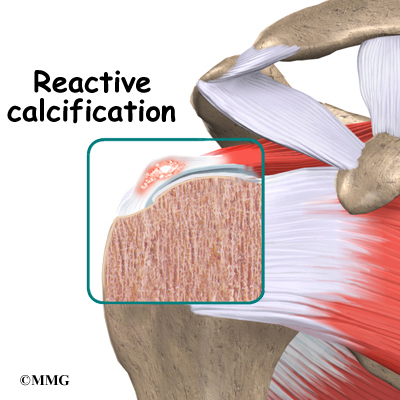

The humeral head of the shoulder is the ball portion of the joint. The humeral head has several blood vessels, which enter at the base of the articular cartilage. Articular cartilage is the smooth, white material that covers the ends of bones in most joints. Articular cartilage provides a slick, rubbery surface that allows the bones to glide over each other as they move. Cartilage also functions as sort of a shock absorber.

The shoulder joint is surrounded by a watertight sac called the joint capsule. The joint capsule holds fluids that lubricate the joint. The walls of the joint capsule are made up of ligaments. Ligaments are connective tissues that attach bones to bones. The joint capsule has a considerable amount of slack, loose tissue, so that the shoulder is unrestricted as it moves through its large range of motion.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Anatomy

Rationale

What conditions lead to shoulder joint replacement?

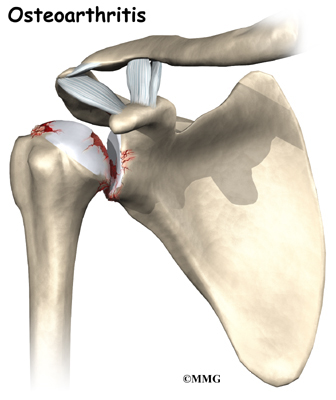

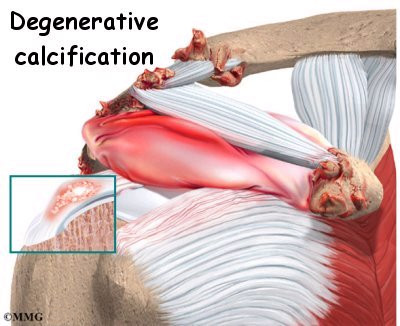

The most common reason for undergoing shoulder replacement surgery is osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis is caused by the degeneration of the joint over time, through wear and tear. Osteoarthritis can occur without any injury to the shoulder, but that is uncommon. Because the shoulder is not a weight-bearing joint, it does not suffer as much wear and tear as other joints. Osteoarthritis is more common in the hip and knee.

Most of the time osteoarthritis occurs many years after an injury to the shoulder. For example, a shoulder dislocation can result in an unstable shoulder. The extra movement or repeated dislocation of the unstable joint causes damage to the articular cartilage and other joint tissues. Over time, this damage leads to osteoarthritis.

Osteoarthritis is not the only type of arthritis that affects the shoulder joint. Systemic diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, may affect any joint in the body. Whatever the type or cause of the arthritis, the shoulder may become painful and difficult to use. If you and your doctor can’t find ways to control your pain, or if it becomes impossible to use your shoulder for daily tasks, your doctor may recommend shoulder replacement surgery.

Certain types of shoulder fractures can injure the blood vessels of the humeral head. The fracture may heal, but the blood vessels don’t. When the blood vessels are damaged, the humeral head no longer has any blood supply. This condition leads to a condition called aseptic necrosis.

In necrosis, parts of the joint surface actually die. Over time, necrosis of the shoulder joint can lead to arthritis. When fractures affect the humeral head, doctors may recommend a shoulder joint replacement. In some cases, the risk of developing necrosis is so high that it makes sense to replace the humeral head immediately.

In most cases, doctors see shoulder replacement surgery as the last option. Sometimes there is a benefit to delaying shoulder replacement surgery as long as possible. Your doctor will probably want you to try nonsurgical measures to control your pain and improve your shoulder movement, including medications and physical or occupational therapy.

Like any arthritic condition, osteoarthritis of the shoulder may respond to anti-inflammatory medications such as aspirin or ibuprofen. Acetaminophen (Tylenol®) may also be prescribed to ease the pain. Some of the newer medications such as glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate are more commonly prescribed today. They seem to be effective in helping reduce the pain of osteoarthritis in all joints. There are also new injectable medications that lubricate the arthritic joint. These medications have been studied mainly in the knee. It is unclear if they will help the arthritic shoulder.

Physical or occupational therapy may be suggested to help you regain as much of the motion and strength in your shoulder as possible before you undergo surgery.

An injection of cortisone into the shoulder joint may give temporary relief. Cortisone is a powerful anti-inflammatory medication that can ease inflammation and reduce pain, possibly for several months. Most surgeons only allow two or three cortisone shots into any joint. If the shots don’t provide you with lasting relief, your doctor may suggest surgery.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Joint Injections for Arthritis

Preparation

What do I need to do to get ready for surgery?

Some severe degenerative problems of the shoulder may require replacement of the painful shoulder with an artificial shoulder joint. You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, you should talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

You may also need to spend time with the physical or occupational therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this pre-operative visit is to record a baseline of information. Your therapist will check your current pain levels, ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each shoulder.

A second purpose of the pre-operative visit is to prepare you for surgery. You’ll begin learning some of the exercises you’ll use during your recovery. And your therapist can help you anticipate any special needs or problems you might have at home, once you’re released from the hospital.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted to the hospital early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before. Come prepared to stay in the hospital for several nights. The length of time you will spend in the hospital depends a lot on you.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during shoulder replacement surgery?

Before we describe the procedure, let’s look first at the artificial shoulder itself.

The Artificial Shoulder

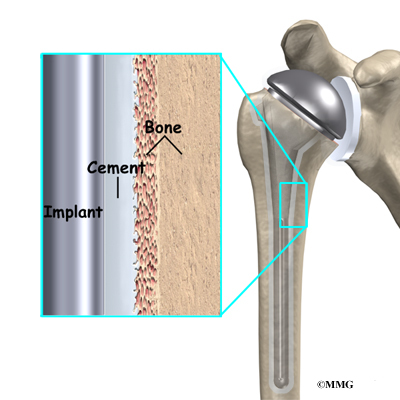

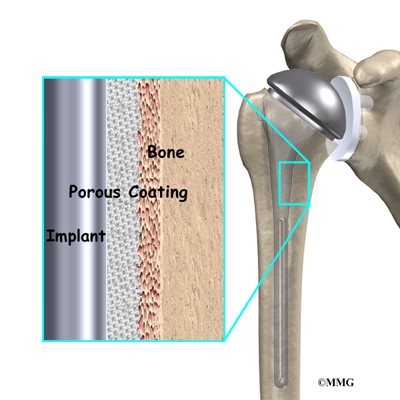

There are two major types of artificial shoulder replacements: a cemented prosthesis and an uncemented prosthesis. A cemented prosthesis is held in place by a type of epoxy cement that attaches the metal to the bone. An uncemented prosthesis has a fine mesh of holes on the surface. Bone grows into the mesh. Over time, this anchors the prosthesis to the bone.

Both types of artificial joints are widely used. Your surgeon may also use a combination of the two types. The surgeon determines the type of replacement joint based on your age, your lifestyle, and the surgeon’s experience.

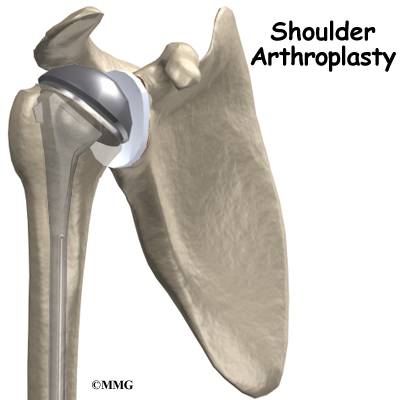

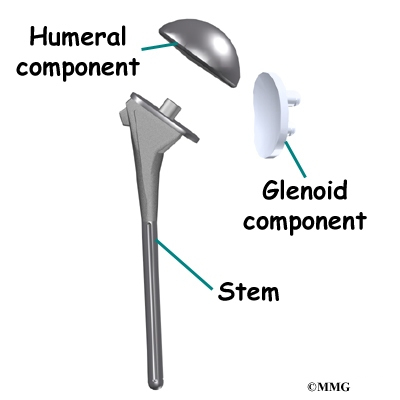

Each prosthesis (artificial joint) is made up of two parts. The humeral component replaces the humeral head, or the ball of the joint. The glenoid component replaces the socket of the shoulder, which is actually part of the scapula.

The humeral component is made of metal. The glenoid component is usually made of two parts. A metal tray attaches directly to the bone, and a plastic cup forms the socket. The plastic is very tough and very slick, much like the articular cartilage it is replacing. In fact, you can ice skate on a sheet of this plastic without causing it much damage.

The Operation

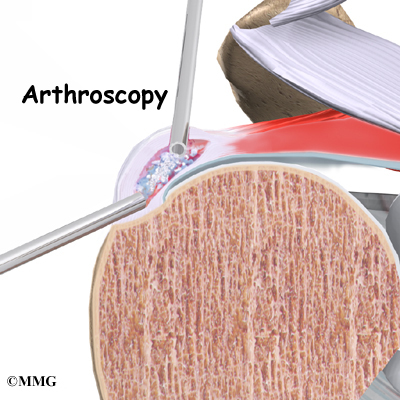

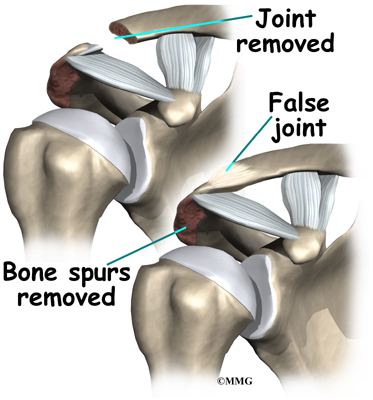

Shoulder replacement surgery can be done in one of two ways. When the cartilage of both the humeral head (the ball) and the glenoid (the socket) is worn away, both parts of the joint must be replaced. This surgery is called arthroplasty, which is the term used for joint reconstruction.

If the glenoid still has some articular cartilage, your surgeon may replace only the humeral head. This procedure is known as a hemiarthroplasty. (Hemi means half.) The hemi-arthroplasty is most commonly used after a fracture of the shoulder where the blood supply to the ball portion (the humeral head) of the humerus is damaged. Research has shown that when the shoulder is being replaced for arthritis, the complete shoulder arthroplasty performs better. Patients have less pain immediately after surgery and in the long run have a better functioning shoulder with less complications and are less likely to need a second operation.

You will most likely need general anesthesia for shoulder replacement surgery. General anesthesia puts you to sleep. It is difficult to numb only the shoulder and arm in a way that makes such a major surgery possible.

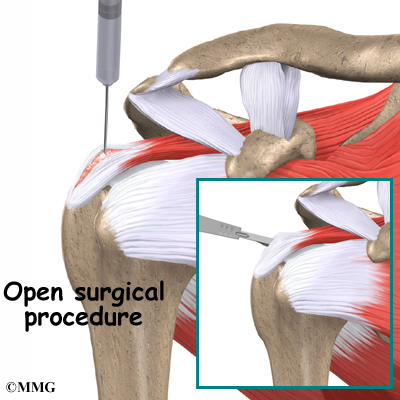

Shoulder replacement surgery is done through an incision on the front of your shoulder. This is called an anterior approach. The surgeon cuts through the skin and then isolates the nerves and blood vessels and moves them to the side. The muscles are also moved to the side.

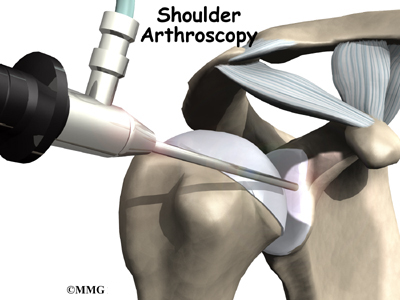

The surgeon enters the shoulder joint itself by cutting into the joint capsule. This allows the surgeon to see the joint.

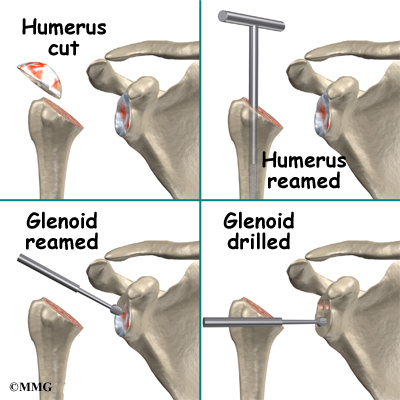

At this point, the surgeon can prepare the bone for attaching the replacement parts. The ball portion of the humeral head is removed with a bone saw. The hollow inside of the upper humerus is prepared using a rasp. This lets your surgeon mold the space to anchor the metal stem of the humeral component inside the bone.

View animation of removing humeral head

View animation of reaming the humerus

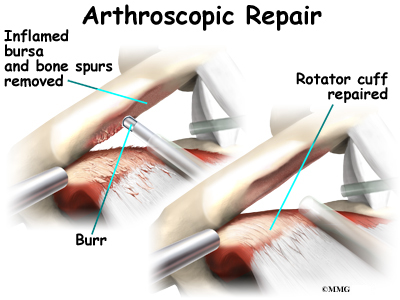

If the glenoid will be replaced, it is prepared by grinding away any remaining cartilage on the surface. This is done with an instrument called a burr. The surgeon usually uses the burr to drill holes into the bone of the scapula. This is where the stem of the glenoid component is anchored.

View animation of preparing the glenoid

View animation of drilling the glenoid

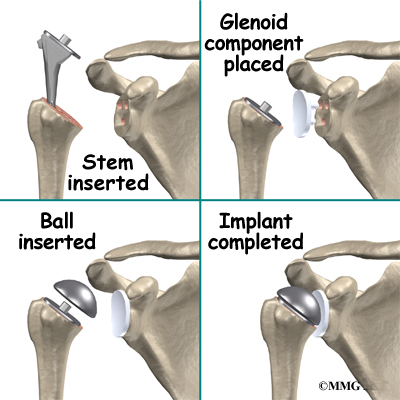

Finally, the humeral component and the glenoid component are inserted and the humeral ball is attached.

View animation of inserting the humeral component

View animation of inserting the glenoid component

View animation of attaching the humeral ball

Once the joint is anchored, the surgeon tests for proper fit. When the surgeon is satisfied with the fit, the joint capsule is stitched together. The muscles are then returned to their correct positions, and the skin is also stitched up.

Your incision will be covered with a bandage, and your arm will be placed in a sling. You will then be woken up and taken to the recovery room.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following artificial shoulder replacement are

- anesthesia

- infection

- loosening

- dislocation

- nerve or blood vessel injury

Anesthesia

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Infection

Infection following joint replacement surgery can be very serious. The chances of developing an infection following artificial joint replacement, however, are low (about one percent). Sometimes infections show up very early, before you leave the hospital. Other times infections may not show up for months, or even years, after the operation.

Infection can also spread into the artificial joint from other infected areas. Once an infection lodges in your joint, it is almost impossible for your immune system to clear it. You may need to take antibiotics when you have dental work or surgical procedures on your bladder and colon. The antibiotics reduce the risk of spreading germs to the artificial joint.

Loosening

The major reason that artificial joints eventually fail is that they loosen where the metal or cement meets the bone. A loose joint prosthesis causes pain. Once the pain becomes unbearable, another operation will probably be needed to fix the artificial joint.

There have been great advances in extending the life of artificial joints. However, most will eventually loosen and require another surgery. In the case of artificial knees, you can expect about 12 to 15 years, but artificial shoulder joints tend to loosen sooner.

Dislocation

Just like your real shoulder, an artificial shoulder can dislocate. A shoulder dislocation occurs when the ball comes out of the socket. There is a greater risk of dislocation right after surgery, before the tissues have healed around the new joint. But there is always a slightly increased risk of dislocation with an artificial joint. Your therapist will teach you how to avoid activities and positions that tend to cause shoulder dislocation. A shoulder that dislocates more than once may need another operation to make it more stable.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Shoulder Dislocations

Nerve or Blood Vessel Injury

All of the large nerves and blood vessels to the arm and hand travel through the armpit. (This area is called the axilla.) Because shoulder replacement surgery takes place so close to the axilla, it is possible that the nerves or blood vessels may be injured during surgery. The resulting problems may be temporary if the injury was caused by stretching to hold the nerves out of the way. The nerves and blood vessels rarely suffer any kind of permanent injury after shoulder replacement surgery, but this type of injury can happen.

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

After surgery, you’ll be transported to the recovery room. You will have a dressing wrapped over your shoulder that will need to be changed frequently over the next few days. Your surgeon may have inserted a small drainage tube into the shoulder joint to help keep extra blood and fluid from building up inside the joint. An intravenous line (IV) will be placed in your arm to give you needed antibiotics and medication.

Your shoulder may be placed in a continuous passive motion (CPM) machine immediately after surgery. CPM helps the shoulder begin moving and alleviates joint stiffness. The machine straps to the shoulder and continuously bends and straightens the joint. This motion is thought to reduce stiffness, ease pain, and keep extra scar tissue from forming inside the joint. You’ll use a shoulder sling to support your arm when you’re not using the CPM machine.

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

A physical or occupational therapist will see you the day after surgery to begin your rehabilitation program. Therapy treatments will gradually improve the movement in your shoulder. If you are using CPM, your therapist will check the alignment and settings. Your therapist will go over your exercises and make sure you are safe getting in and out of bed and moving about in your room.

When you go home, you may get home therapy visits. By visiting your home, your therapist can check to see that you are safe getting around in your home. Treatments will also be done to help improve your range of motion and strength. In some cases, you may require up to three visits at home before beginning outpatient therapy.

The first few outpatient treatments will focus on controlling pain and swelling. Ice and electrical stimulation treatments may help. Your therapist may also use massage and other types of hands-on treatments to ease muscle spasm and pain. Continue to use your shoulder sling as prescribed.

As the rehabilitation program evolves, more challenging exercises are chosen to safely advance the shoulder’s strength and function.

Finally, a select group of exercises can be used to simulate day-to-day activities, like grooming your hair or getting dressed. Specific exercises may also be chosen to simulate work or hobby demands.

When your shoulder range of motion and strength have improved enough, you’ll be able to gradually get back to normal activities. Ideally, you’ll be able to do almost everything you did before. However, you may need to avoid heavy or repeated shoulder actions.

You may be involved in a progressive rehabilitation program for two to four months after surgery to ensure the best results from your artificial joint. In the first six weeks after surgery, you should expect to see your therapist two to three times a week. At that time, if everything is still going as planned, you may be able to advance to a home program. Then you will only check in with your therapist every few weeks.