Hip

Hip Anatomy Animated Tutorial

Artificial Joint Replacement of the Hip, Anterior Approach

A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Joint Replacement of the Hip, Anterior Approach

Introduction

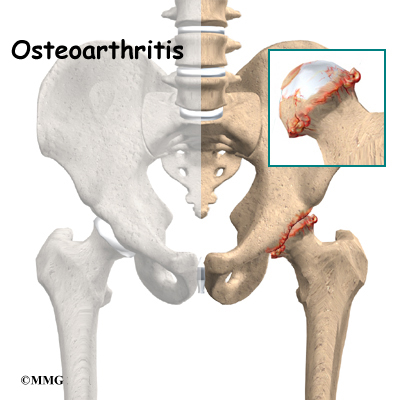

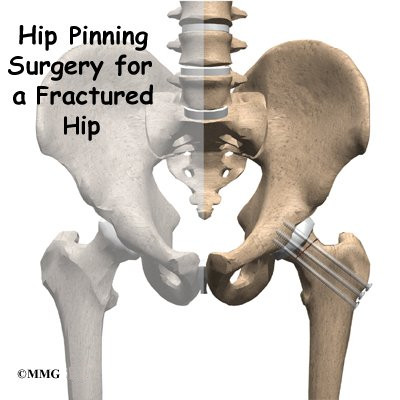

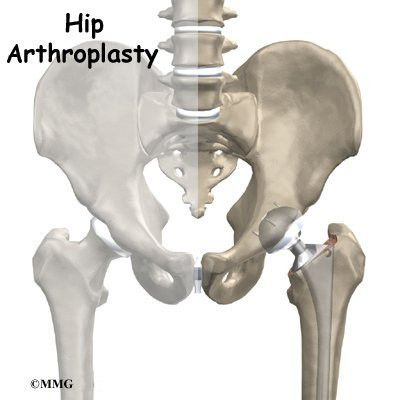

A hip that is painful as a result of osteoarthritis (OA) can severely affect your ability to lead a full, active life. Over the last 25 years, major advancements in hip replacement have improved the outcome of the surgery greatly. Hip replacement surgery (also called hip arthroplasty) is becoming more and more common as the population of the world begins to age.

There are several different ways of entering the hip joint to perform surgery on the hip; these are referred to by orthopaedic surgeons as “approaches” to the hip. The two most common approaches used in the past to perform artificial hip replacement are the “posterior” approach and the “anterolateral” approach. A new, less invasive approach to the hip joint that was pioneered over the last 20 years is being used more frequently today. Each approach has its own benefits, but the newer anterior approach is felt by many to be the best option today. In this document, we will be discussing the anterior approach.

In addition to reading this article, be sure to watch our Artificial Hip Replacement Anterior Approach (Hip Arthroplasty) Animated Tutorial Video.

This guide will help you understand

- what your surgeon hopes to achieve

- the benefits of the anterior approach

- what happens during the procedure

- what to expect after your operation

Anatomy

How does the hip normally work?

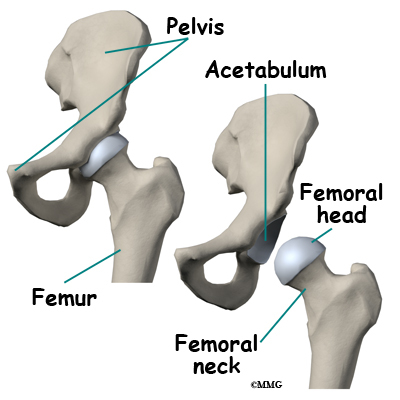

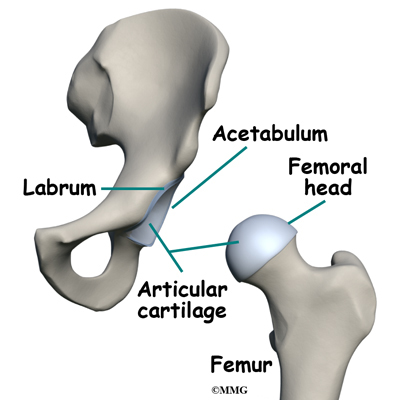

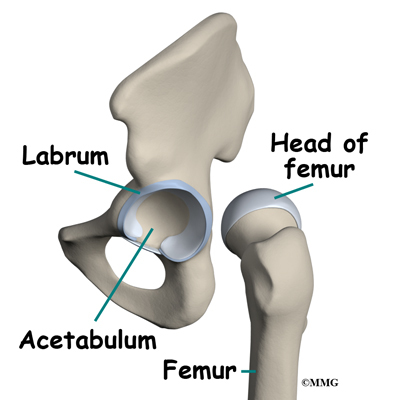

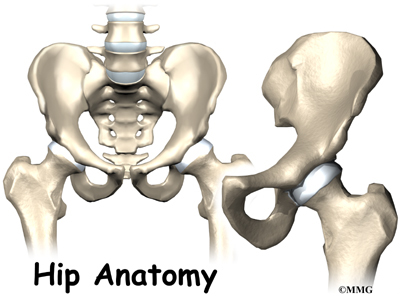

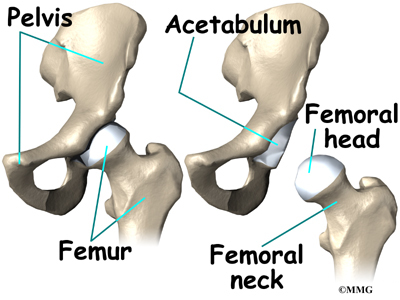

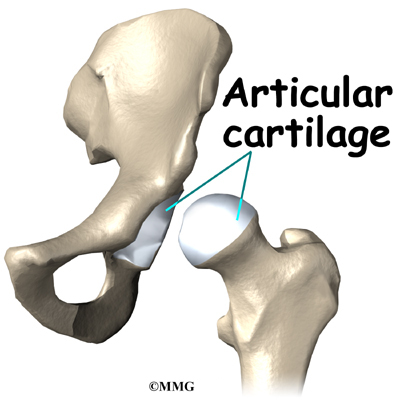

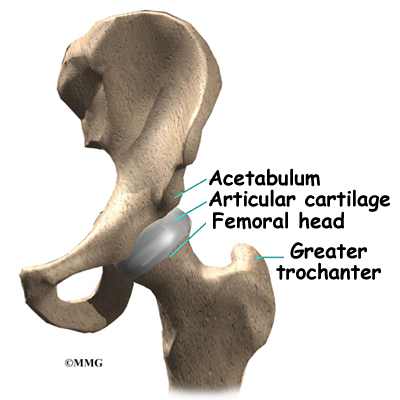

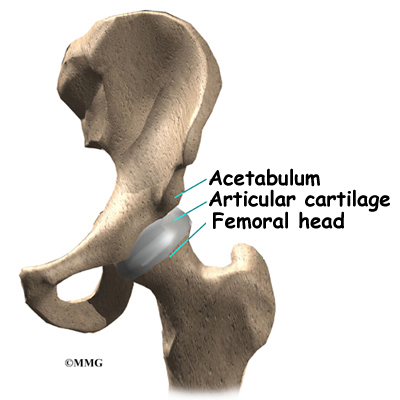

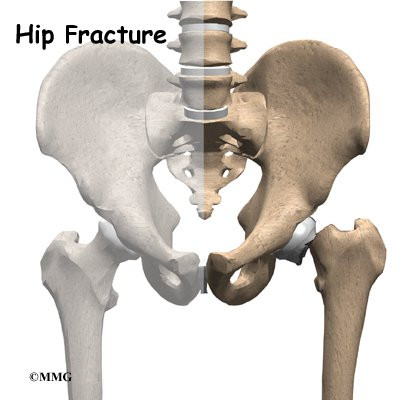

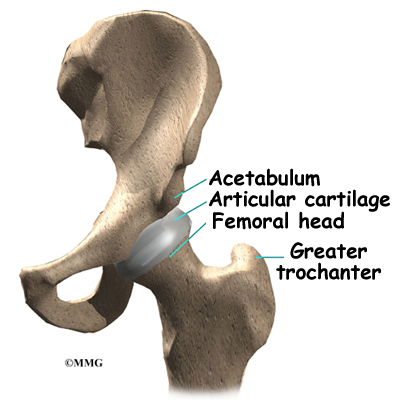

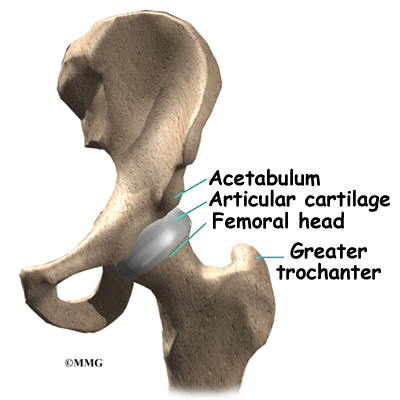

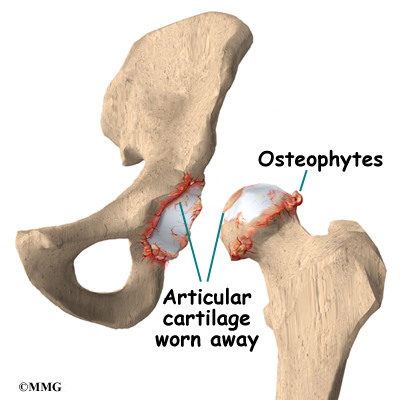

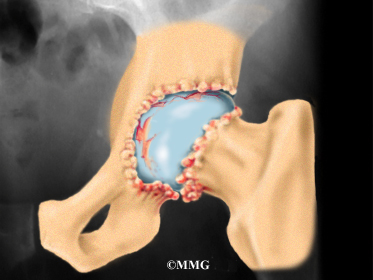

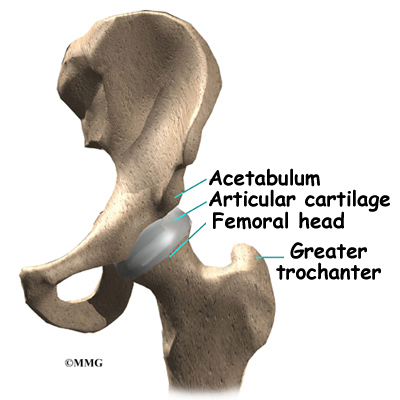

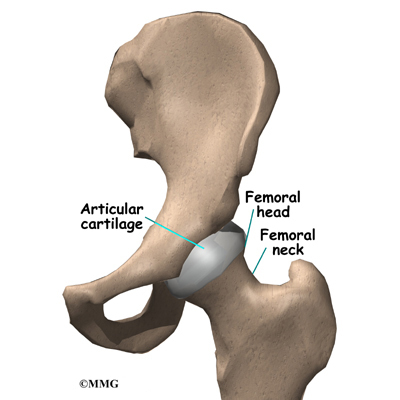

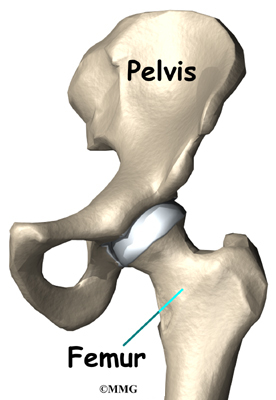

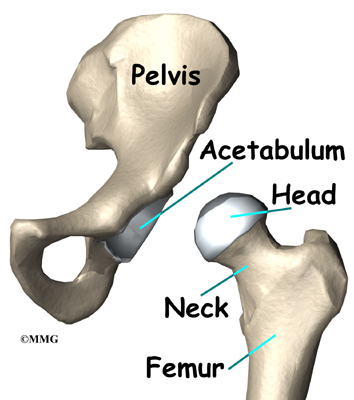

The hip joint is one of the true ball-and-socket joints of the body. The hip socket is called the acetabulum and forms a deep cup that surrounds the ball of the upper thigh bone, known as the femoral head. The thick muscles of the buttock at the back and the thick muscles of the thigh in the front surround the hip.

The surface of the femoral head and the inside of the acetabulum are covered with articular cartilage. This material is about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large joints. Articular cartilage is a tough, slick material that allows the surfaces to slide against one another without damage.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hip Anatomy

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to achieve?

The main reason for replacing any arthritic joint with an artificial joint is to stop the bones from rubbing against each other. This rubbing causes pain. Replacing the painful and arthritic joint with an artificial joint gives the joint a new surface, which moves smoothly without causing pain. The goal is to help people return to many of their activities with less pain and greater freedom of movement.

Over the last decade, many surgeons have begun using smaller and smaller incisions to perform surgeries that once required larger incisions. This has been made possible due to the development of better tools and techniques to perform the procedures, as well as the use of computer assisted imaging. This trend is sometimes referred to as minimally invasive surgery.

There are many benefits to using smaller incisions including less damage to normal tissue and less blood loss. The anterior approach does not require the cutting of any muscles or tendons around the hip joint. Patients tend to recover quicker and are able to leave the hospital sooner after surgery. In the case of artificial hip replacement, using a smaller incision can result in less damage to the ligaments around the hip that provide stability to the joint. This means that the risk of dislocation of the artificial joint during recovery after surgery is lessened.

Many surgeons have adopted the anterior approach to the hip joint in order to utilize these minimally invasive techniques. Many research studies show that the risk of dislocation after surgery when using the anterior approach is significantly less that other approaches. The anterior approach is considered to be the most stable of all the approaches to the hip.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Osteoarthritis of the Hip

Preparation

How should I prepare for surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery should be made jointly by you and your surgeon only after you feel that you understand as much about the procedure as possible.

Once the decision to proceed with surgery is made, several things may need to be done. Your orthopedic surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your medical or family doctor. This is to ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation. You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after the surgery.

One purpose of the preoperative physical therapy visit is to record a baseline of information. This includes measurements of your current pain levels, functional abilities, and the movement and strength of each hip.

A second purpose of the preoperative therapy visit is to prepare you for your upcoming surgery. You will begin to practice some of the exercises you will use just after surgery. You will also be trained in the use of either a walker or crutches. Whether the surgeon uses a cemented or noncemented approach may determine how much weight you will be able to apply through your foot while walking.

This procedure requires the surgeon to open up the hip joint during surgery. This puts the hip at some risk for dislocation after surgery. To prevent dislocation, patients follow guidelines about which hip positions to avoid (called hip precautions). Your therapist will review these precautions with you during the preoperative visit and will drill you often to make sure you practice them at all times for at least six weeks. Some surgeons give the OK to discontinue the precautions after six to 12 weeks because they feel the soft tissues have gained enough strength by this time to keep the joint from dislocating. Finally, the therapist assesses any needs you will have at home once you’re released from the hospital.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Hip Dislocation Precautions

You may be asked to donate some of your own blood before the operation. Because of the trend towards newer minimally invasive techniques, hip replacement surgery today results in much less blood loss during surgery. You probably will not be asked to donate blood and probably will not require a blood transfusion after surgery. But, if your surgeon feels the surgery may be more complex and require a blood transfusion after surgery, this blood can be donated three to five weeks before the operation. During the time before the operation, your body will make new blood cells to replace the loss. At the time of the operation, if you need to have a blood transfusion you will receive your own blood back from the blood bank.

Surgical Procedure

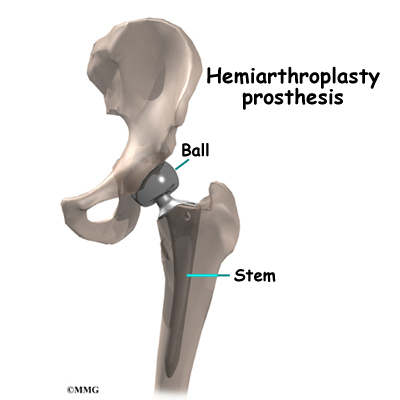

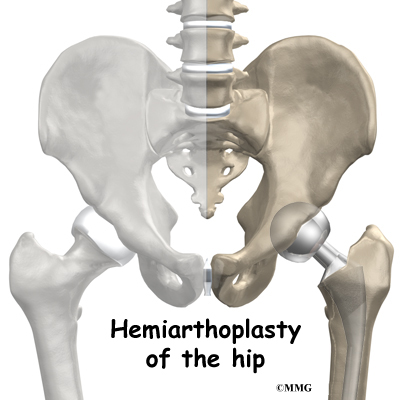

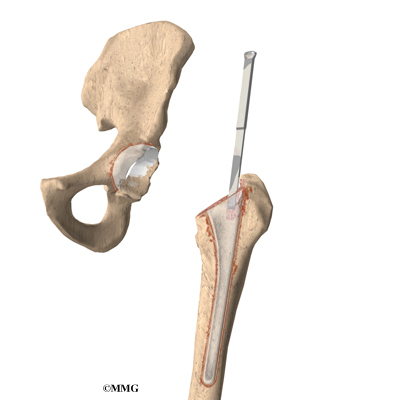

Before we describe the procedure, let’s look first at the artificial hip itself.

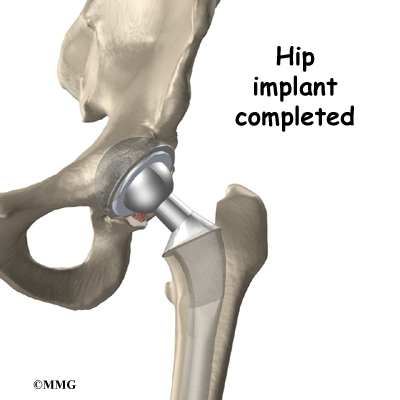

The Artificial Hip

There are two major types of artificial hip replacements:

- cemented prosthesis

- noncemented prosthesis

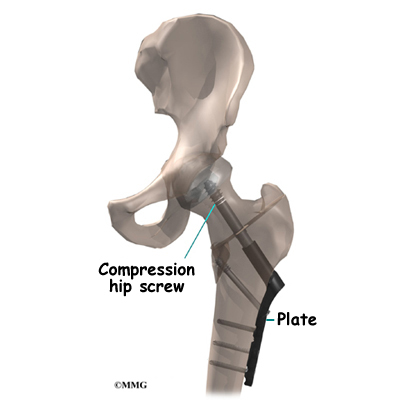

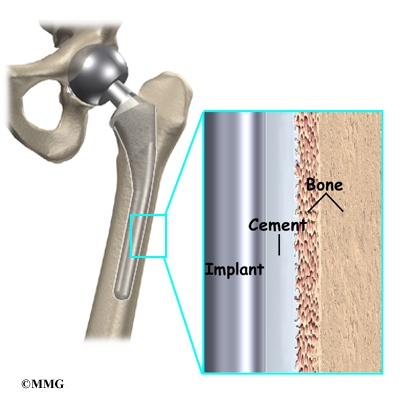

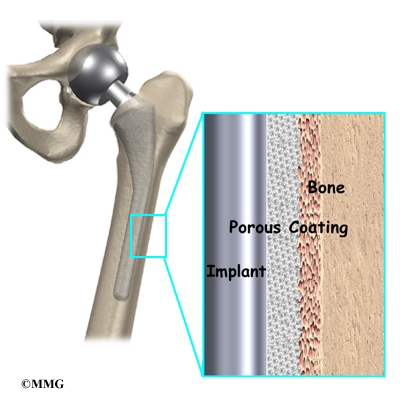

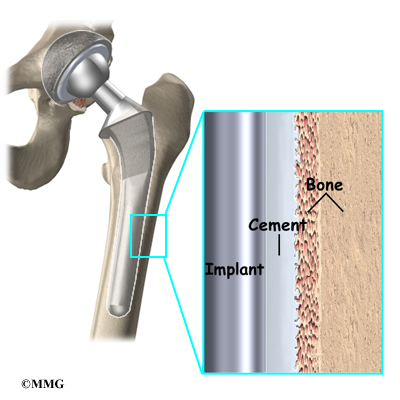

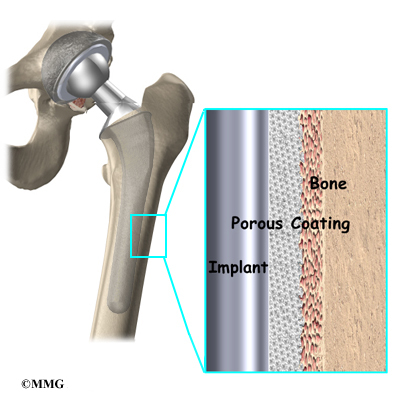

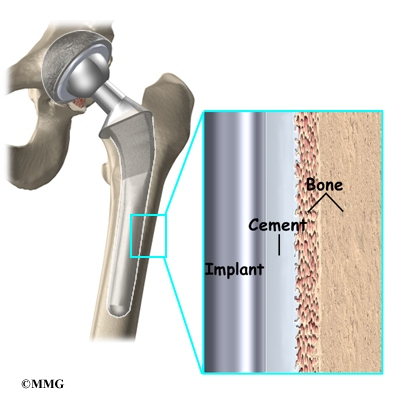

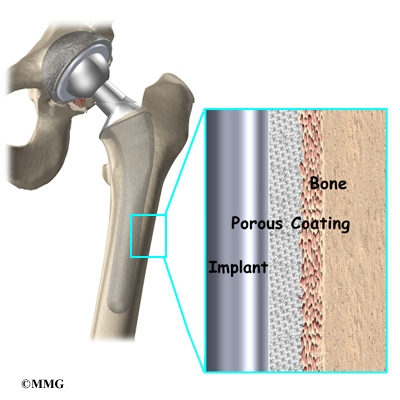

A cemented prosthesis is held in place by a type of epoxy cement that attaches the metal to the bone. An noncemented prosthesis bears a fine mesh of holes on the surface that allows bone to grow into the mesh and attach the prosthesis to the bone.

Both are still widely used. In some cases a combination of the two types is used in which the ball portion of the prosthesis is cemented into place, and the socket not cemented. The decision about whether to use a cemented or noncemented artificial hip is usually made by the surgeon based on your age and lifestyle, and the surgeon’s experience.

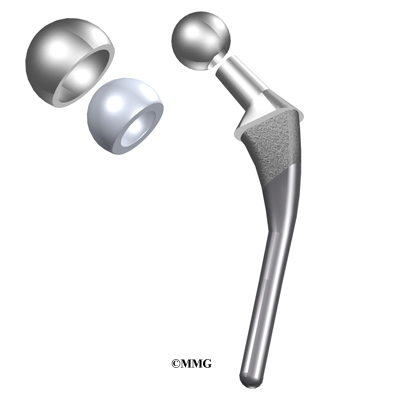

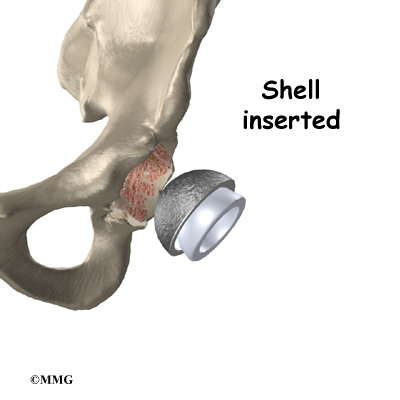

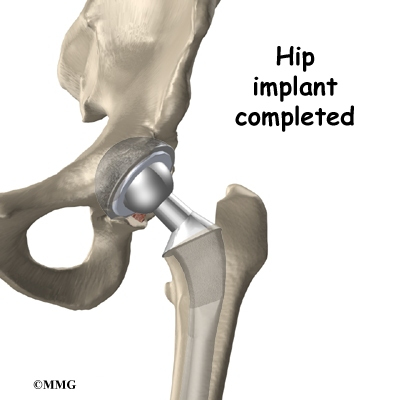

Each prosthesis is made of two main parts. The acetabular component (socket) replaces the acetabulum. The acetabular component is made of a metal shell with a plastic inner liner that provides the bearing surface. The plastic used is so tough and slick that you could ice skate on a sheet of it without much damage to the material.

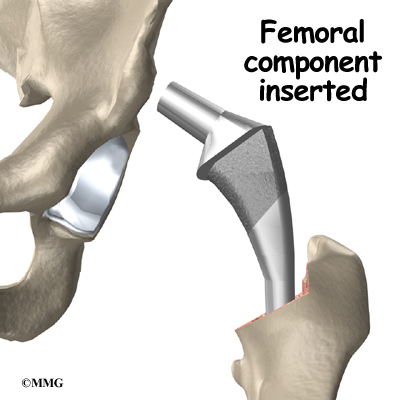

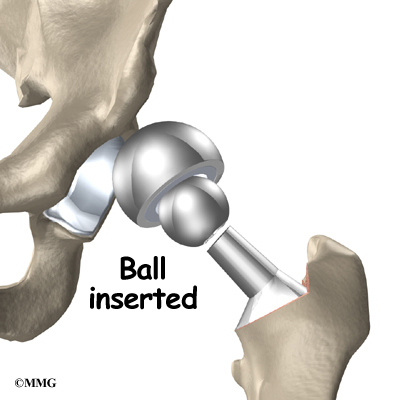

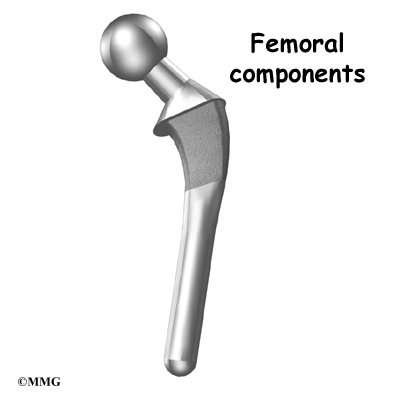

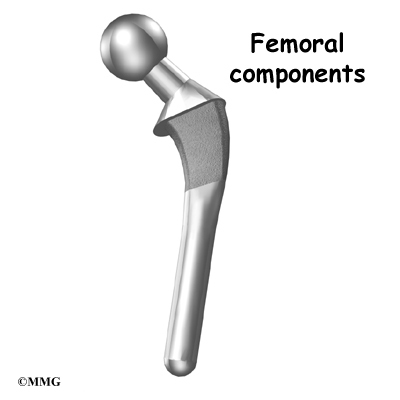

The femoral component (stem and ball) replaces the femoral head. The femoral component is made of metal. Sometimes, the metal stem is attached to a ceramic ball.

The Operation

Some type of anesthesia is necessary to perform a hip replacement. The procedure can be performed under general anesthesia or using some type of spinal anesthesia, such as an epidural or spinal. General anesthesia means that you are put completely asleep and a tube inserted into your windpipe to breathe for you while you are under the anesthesia. With a spinal type of anesthetic, you will be numb from the waist down after receiving an injection of anesthetic medication into your spinal canal. You will probably also be given medications to make you unaware of what is going on around you, but you will not have a tube inserted into your windpipe – you will breathe on your own. You should plan on discussing your options with your surgeon and anesthesiologist.

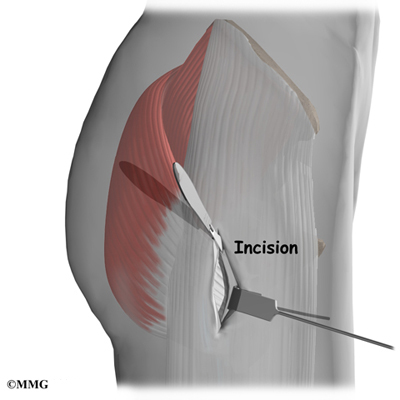

The surgeon begins by making an incision on the side of the thigh to allow access to the hip joint. Several different approaches can be used to make the incision. The choice is usually based on the surgeon’s training and preferences. For the anterior approach, an incision is made on the side of the thigh. This incision is usually around 4 to 6 inches but may be lengthened if more room is needed to complete the operation.

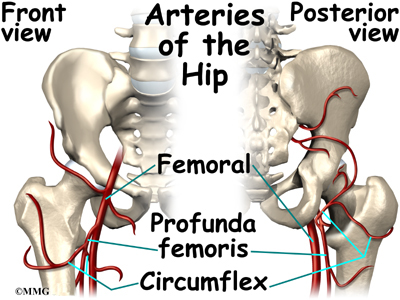

Once the skin incision is made, the muscles below the skin are separated to allow access to the hip joint. The nerves and blood vessels that run down the thigh in front of the hip joint are protected with special metal retractors. The anterior hip capsule that covers the front of the hip joint is opened by making an incision in the joint capsule.

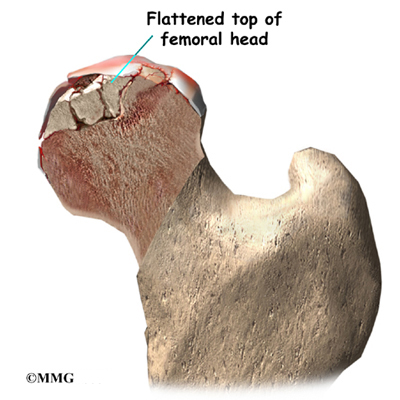

Once the hip joint is entered, the surgeon dislocates the femoral head from the acetabulum. Then the femoral head is removed by cutting through the femoral neck with a power saw.

Attention is then turned toward the socket. The surgeon uses a power drill and a special reamer (a cutting tool used to enlarge or shape a hole) to remove cartilage from inside the acetabulum. The surgeon shapes the socket into the form of a half-sphere. This is done to make sure the metal shell of the acetabular component will fit perfectly inside. After shaping the acetabulum, the surgeon tests the new component to make sure it fits just right.

In the noncemented variety of artificial hip replacement, the metal shell is held in place by the tightness of the fit or by using screws to hold the shell in place. In the cemented variety, a special epoxy-type cement is used to anchor the acetabular component to the bone.

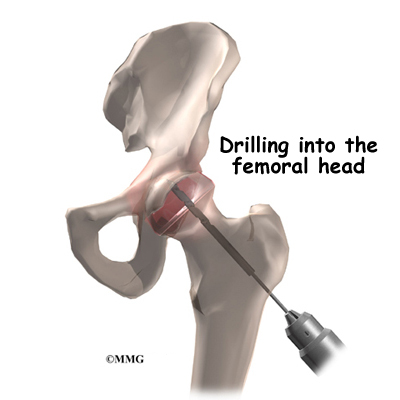

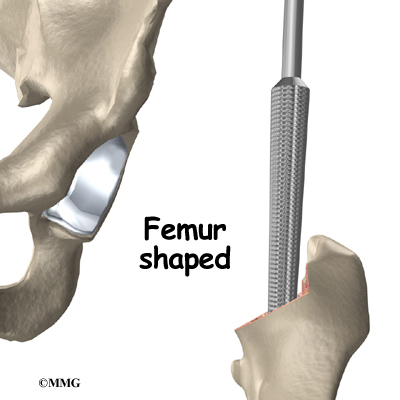

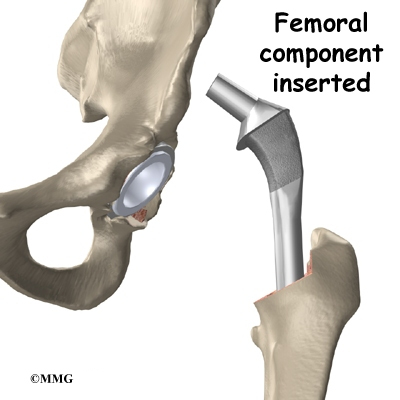

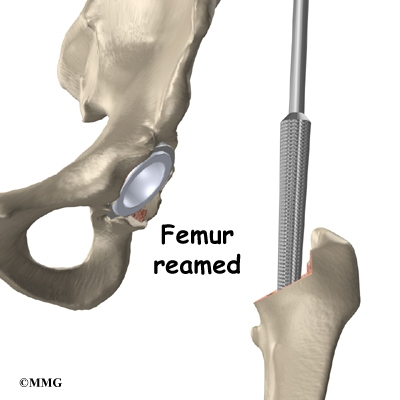

To begin replacing the femur, a drill is used to create the initial space to begin the process of preparing the femoral canal. Once the drilling is complete special rasps (filing tools) are used to shape the hollow femur to the exact shape of the metal stem of the femoral component. Once the size and shape are satisfactory, the stem is inserted into the femoral canal.

Again, in the noncemented variety of femoral component the stem is held in place by the tightness of the fit into the bone (similar to the friction that holds a nail driven into a hole that is slightly smaller than the diameter of the nail). In the cemented variety, the femoral canal is enlarged to a size slightly larger than the femoral stem, and the epoxy-type cement is used to bond the metal stem to the bone.

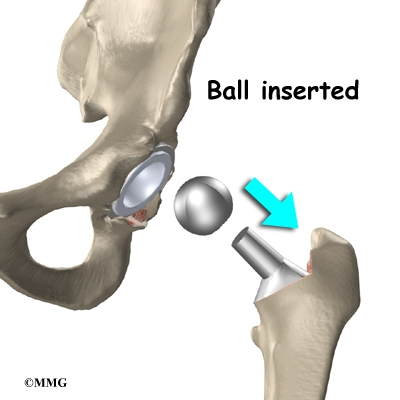

The metal ball that makes up the femoral head is then inserted. The hip is relocated and tested for range of motion and stability. The surgeon literally moves the leg in a full range of motion while watching the ball move in the plastic socket. The purpose of this step is to make sure that the hip moves well through the normal range of motion and does not tend to dislocate.

Once the surgeon is satisfied that everything fits properly, the incision is closed with stitches. Several layers of stitches are used under the skin, and either stitches or metal staples are then used to close the skin. A bandage is applied to the incision, and you are returned to the recovery room.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following hip replacement surgery include

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be given during surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but it is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when the blood in the large veins of the leg forms blood clots. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Infection can be a very serious complication following artificial joint replacement surgery. The chance of getting an infection following total hip replacement is probably around one percent. Some infections may show up very early, even before you leave the hospital. Others may not become apparent for months, or even years, after the operation. Infection can spread into the artificial joint from other infected areas. Your surgeon may want to make sure that you take antibiotics when you have dental work or surgical procedures on your bladder or colon to reduce the risk of spreading germs to the joint.

Dislocation

Just like your real hip, an artificial hip can dislocate if the ball comes out of the socket. There is a greater risk just after surgery, before the tissues have healed around the new joint, but there is always a risk. Once of the reasons that surgeons choose the anterior approach is that the risk of dislocation is much less than other approaches. But, there is still a small risk of dislocation even after using the anterior approach. The physical therapist will instruct you very carefully how to avoid activities and positions which may have a tendency to cause a hip dislocation. A hip that dislocates more than once may need to have another operation to make it more stable.

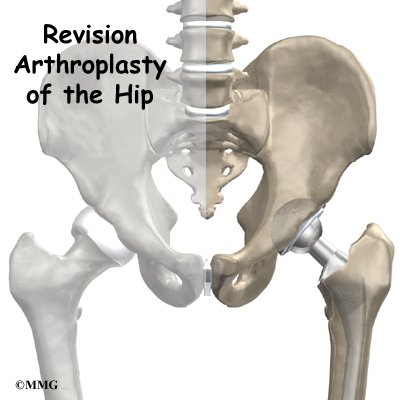

Loosening

The main reason that artificial joints eventually fail continues to be the loosening of the metal or cement from the bone. Great advances have been made in extending how long an artificial joint will last,but any artificial joint may eventually loosen and require a revision. A “revision” is the term used to describe removing the old artificial joint parts and replacing them with new parts. Today you can expect 15 to 20 years of service from an artificial hip, but in some cases the hip will loosen earlier than that. A loose hip is a problem because it causes pain. Once the pain becomes unbearable, another operation will probably be required to revise the hip.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Revision Arthroplasty of the Hip

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

After surgery, your hip will be covered with a padded dressing. Special boots and stockings are usually placed on your feet and legs to help prevent blood clots from forming.

If your surgery was performed under general anesthesia, a nurse or respiratory therapist will visit your room to guide you in a series of breathing exercises. You’ll use an incentive spirometer to improve breathing and avoid possible problems with pneumonia.

Physical therapy treatments are scheduled one to three times each day as long as you are in the hospital. Your first treatment is scheduled soon after you wake up from surgery. Your therapist will begin by helping you move from your hospital bed to a chair. By the second day, you’ll begin walking longer distances using your crutches or walker. Most patients are safe to put comfortable weight down when standing or walking. However, if your surgeon used a noncemented prosthesis, you may be instructed to limit the weight you bear on your foot when you are up and walking. Your therapist will review exercises to begin toning and strengthening the thigh and hip muscles. Ankle and knee movements are used to help pump swelling out of the leg and to prevent the formation of blood clots.

Patients are usually able to go home after spending one to four days in the hospital. You’ll be on your way home when you can demonstrate a safe ability to get in and out of bed, walk up to 75 feet with your crutches or walker, go up and down stairs safely, and consistently remember to use your hip precautions. Patients who still need extra care may be sent to a rehabilitation unit until they are safe and ready to go home.

Most orthopedic surgeons recommend that you have checkups on a routine basis after your artificial joint replacement. How often you need to be seen varies from every six months to every five years, according to your situation and what your surgeon recommends.

Patients who have an artificial joint will sometimes have episodes of pain, but if you have a period that lasts longer than a couple of weeks you should consult your surgeon. During the examination, the orthopedic surgeon will try to determine why you are feeling pain. X-rays may be taken of your artificial joint to compare with the ones taken earlier to see whether the joint shows any evidence of loosening.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect during my recovery?

After you are discharged from the hospital, your therapist may see you for one to six in-home treatments. This is to ensure you are safe in and about the home and getting in and out of a car. Your therapist will review your exercise program, continue working with you on your hip precautions, and make recommendations about your safety. These safety tips include using raised commode seats and bathtub benches, and raising the surfaces of couches and chairs. This keeps your hip from bending too far when you sit down. Bath benches and handrails can improve safety in the bathroom. Other suggestions may include the use of strategic lighting and the removal of loose rugs or electrical cords from the floor.

You should use your walker or crutches as instructed. You surgeon will advise you and your therapist how fast you can increase the weight you place through your leg. Most patients progress to using a cane in two to four weeks. In some cases, you may allowed to bear full weight almost immediately.

You may have your sutures or staples removed ten days to two weeks after surgery. Patients are usually able to drive within three weeks and walk without a walking aid by six weeks. Upon the approval of the surgeon, patients are generally able to resume sexual activity by one to two months after surgery.

The need for physical therapy usually requires a few visits in outpatient physical therapy. More visits may be needed for patients who have problems walking or who need to get back to heavier types of work or activities. Therapists sometimes treat their patients in a pool. Exercising in a swimming pool puts less stress on the hip joint, and the buoyancy lets you move and exercise easier. Once you’ve gotten your pool exercises down and the other parts of your rehab program advance, you may be instructed in an independent program. When you are safe in putting full weight through the leg, several types of balance exercises can be chosen to further stabilize and control the hip.

Finally, if your surgeon feels additional physical therapy is necessary, a select group of exercises can be used to simulate day-to-day activities, such as going up and down steps, squatting, and walking on uneven terrain. Specific exercises may then be chosen to simulate work or hobby demands.

Many patients have less pain and better mobility after having hip replacement surgery. But, you will need to follow some guidelines to help keep your new joint healthy for as long as possible. This may require that you adjust your activity choices to keep from putting too much strain on your new hip joint. Heavy sports that require running, jumping, quick stopping and starting, and cutting are discouraged. Patients may need to consider alternate jobs to avoid work activities that require heavy demands of lifting, crawling, and climbing.

<!–

//Document link: A Patient’s Guide to Rehabilitation After Total Hip Replacement; rehab_thr.txt]

–>

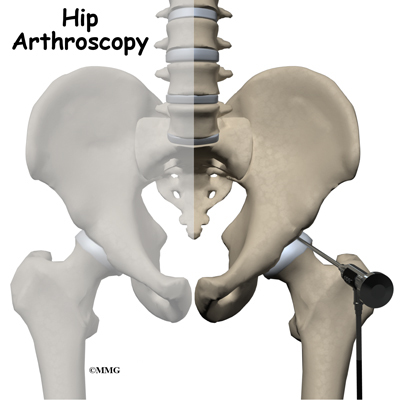

Hip Arthroscopy

A Patient’s Guide to Hip Arthroscopy

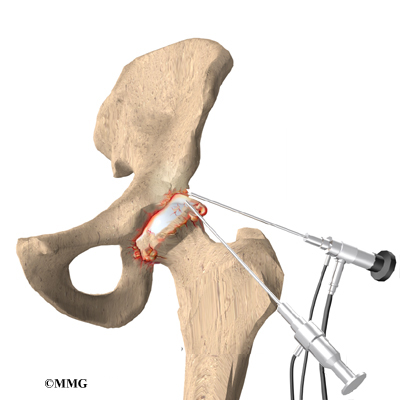

Introduction

A hip arthroscopy is a procedure where a small video camera attached to a fiberoptic lens is inserted into the hip joint to allow a surgeon to see without making a large incision. Arthroscopy is now used to evaluate and treat orthopedic problems in many different joints of the body. While not as common as arthroscopy of the knee and shoulder, hip arthroscopy is used to evaluate and treat certain problems affecting the hip joint and the space outside the hip joint known as the greater trochanteric bursa.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the hip are treated during hip arthroscopy

- what types of conditions are treated with hip arthroscopy

- what to expect before and after hip arthroscopy

Anatomy

What parts of the hip are involved?

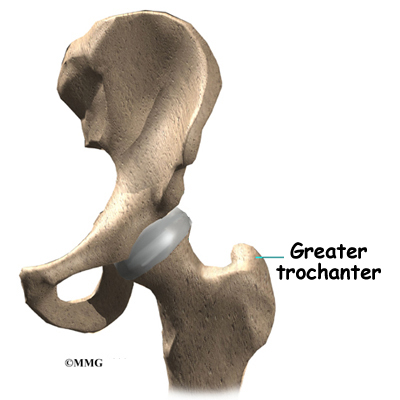

The hip joint is one of the true ball-and-socket joints of the body. The hip socket is called the acetabulum and forms a deep cup that surrounds the ball of the upper thigh bone. The thigh bone itself is called the femur, and the ball on the end is the femoral head. The ball and socket arrangement gives the hip a large amount of motion needed for daily activities like walking, squatting, and stair-climbing.

The surfaces of the femoral head and the inside of the acetabulum are covered with articular cartilage. This material is about one-quarter of an inch thick in most large joints. Articular cartilage is a tough, slick material that allows the surfaces to slide against one another without damage.

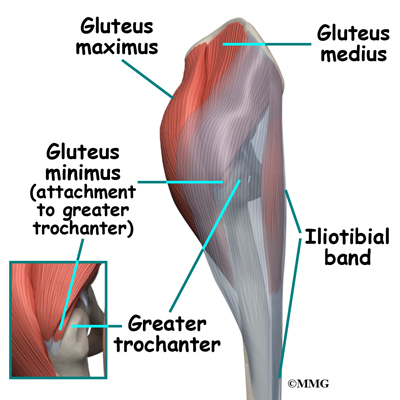

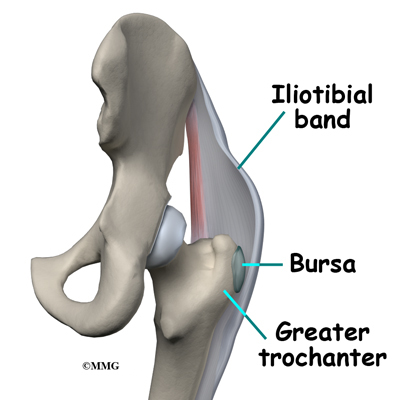

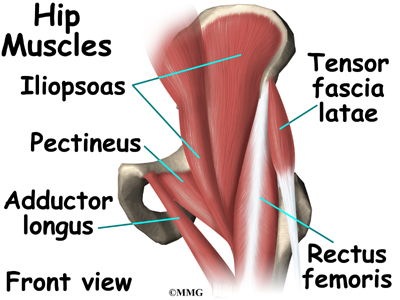

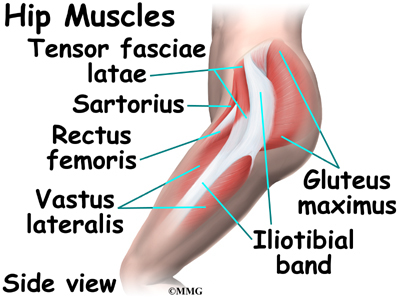

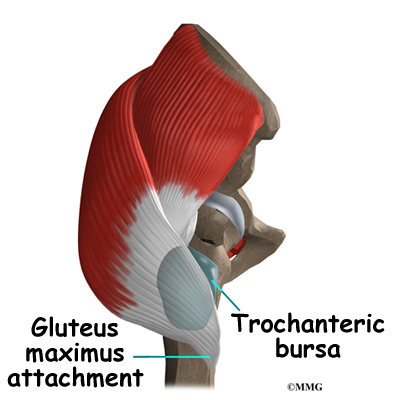

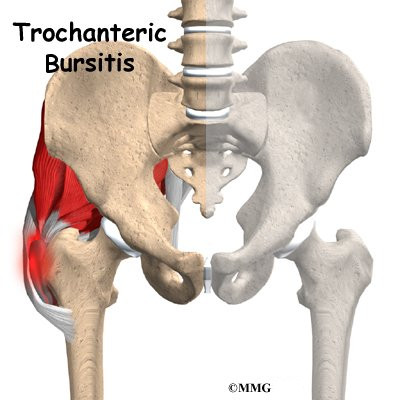

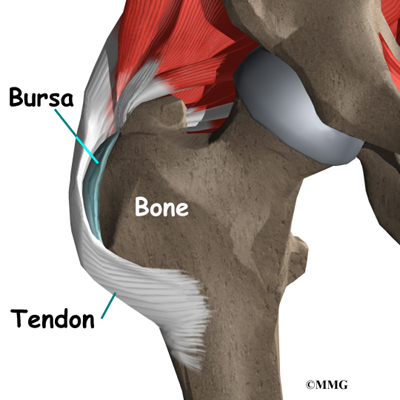

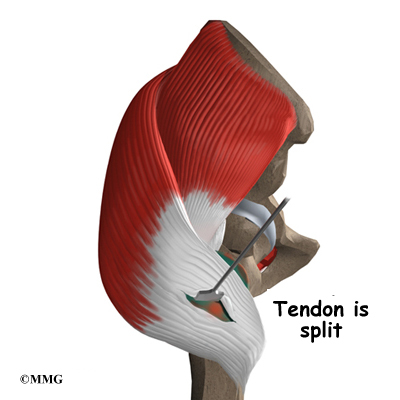

The gluteus maximus is the largest of three gluteal muscles of the buttock. This muscle spans the side of the hip and joins the iliotibial band. The iliotibial band is a long tendon that passes over the bursa on the outside of the greater trochanter. It runs down the side of the thigh and attaches just below the outside edge of the knee. Two other buttock muscles attach to the greater trochanter, the gluteus medius and the gluteus minimus. These muscles are known as the abductors because they function to pull the lower leg away from the body – a motion that is called abduction. These muscles can be torn where they attach to the greater trochanter causing pain and and weakness as well as a snapping sensation.

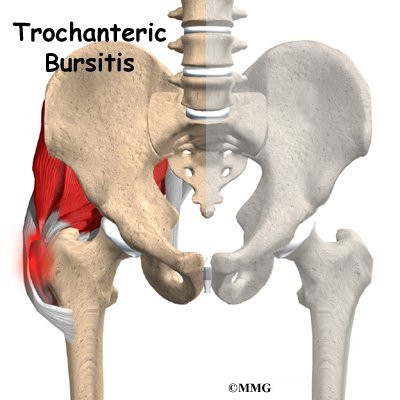

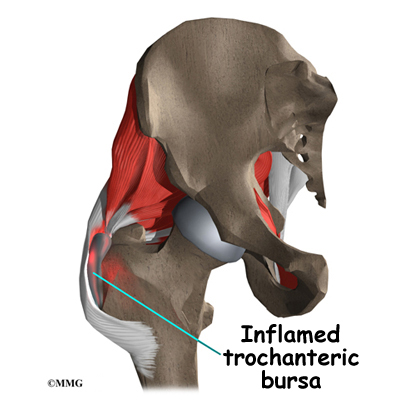

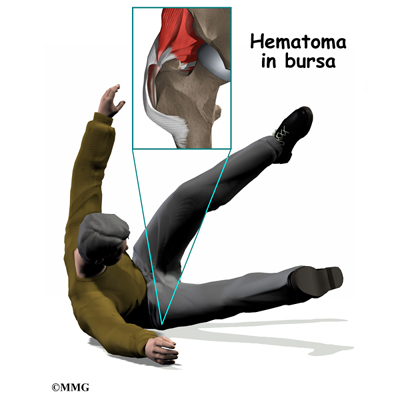

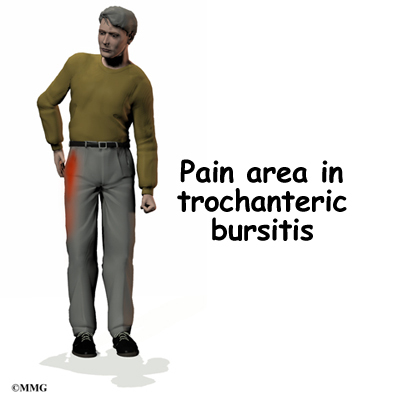

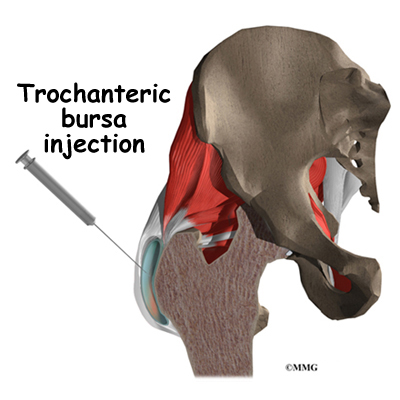

Where friction must occur between muscles, tendons, and bones, there is usually a bursa. A bursa is a thin sac of tissue that contains a bit of fluid to lubricate the area where the friction occurs. The bursa is a normal structure, and the body will even produce a bursa in response to friction. The bursa next to the greater trochanter is called the greater trochanteric bursa.

The hip joint is surrounded by a water-tight pocket called the joint capsule. This capsule is formed by ligaments, connective tissue and synovial tissue. When the joint capsule is filled with sterile saline and is distended, the surgeon can insert the arthroscope into the pocket that is formed, turn on the lights and the camera and see inside the hip joint as if looking into an aquarium. The surgeon can see nearly everything that is inside the hip joint including: (1) the joint surfaces of the femoral head and acetabulum (2) the acetabular labrum and (3) the synovial lining of the joint.

The arthroscope can also be inserted into the space outside the hip joint – the greater trochanteric bursa. This allows the surgeon to see the attachment of the gluteus medius muscle and the inside of the bursa.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hip Anatomy

Rationale

What does my surgeon hope to accomplish?

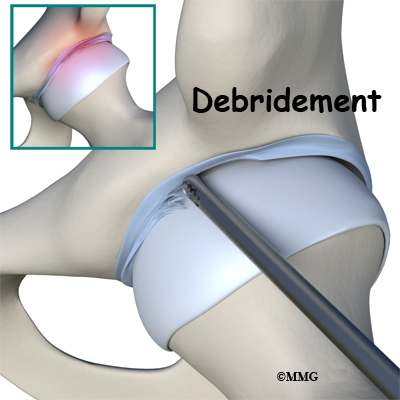

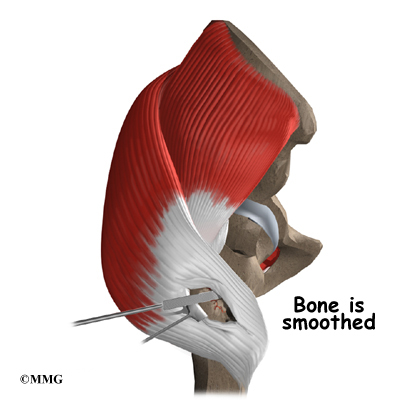

When hip arthroscopy first became available it was used primarily to look inside the hip joint and make a diagnosis. Today, hip arthroscopy is used in performing a wide range of different types of surgical procedures on the hip joint including confirming a diagnosis, removing loose bodies, removing or repairing a torn labrum, debriding excess inflamed bursa tissue, repairing a tear in the gluteus medius tendon and fixing fractures of the joint surface.

Your surgeon’s goal is to fix or improve your problem by performing a suitable surgical procedure; the arthroscope is a tool that improves the surgeons ability to perform that procedure. The arthroscope image is magnified and allows the surgeon to see better and clearer. The arthroscope allows the surgeon to see and perform surgery using much smaller incisions. This results in less tissue damage to normal tissue and can shorten the healing process. But remember, the arthroscope is only a tool. The results that you can expect from a hip arthroscopy depend on what is wrong with your hip, what can be done inside your hip to improve the problem and your effort at rehabilitation after the surgery.

Preparations

What do I need to know before surgery?

You and your surgeon should make the decision to proceed with surgery together. You need to understand as much about the procedure as possible. If you have concerns or questions, be sure and talk to your surgeon.

Once you decide on surgery, you need to take several steps. Your surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your regular doctor. This exam helps ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation.

You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after surgery. This allows you to get a head start on your recovery. One purpose of this preoperative visit is to record a baseline of information. The therapist will check your current pain levels, ability to do your activities, and the movement and strength of each hip.

A second purpose of the preoperative visit is to prepare you for surgery. The therapist will teach you how to walk safely using crutches or a walker. And you’ll begin learning some of the exercises you’ll use during your recovery.

On the day of your surgery, you will probably be admitted for surgery early in the morning. You shouldn’t eat or drink anything after midnight the night before.

Surgical Procedure

What happens during hip arthroscopy?

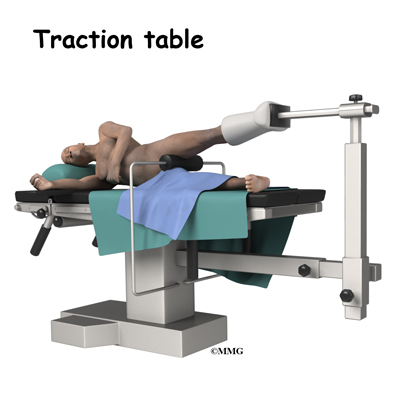

Before surgery you will be placed under either general anesthesia or a type of spinal anesthesia. A special operating room table called a traction table will be used.

The hip joint is very tight with little space between the ball and the socket. By applying traction, the surgeon is able to increase this space and allow the arthroscope to be inserted into that space. The end of the arthroscope will be moved about in this space to look throughout the joint. Finally, sterile drapes are placed to create a sterile environment for the surgeon to work. There is a great deal of equipment that surrounds the operating table including the TV screens, cameras, light sources, and surgical instruments.

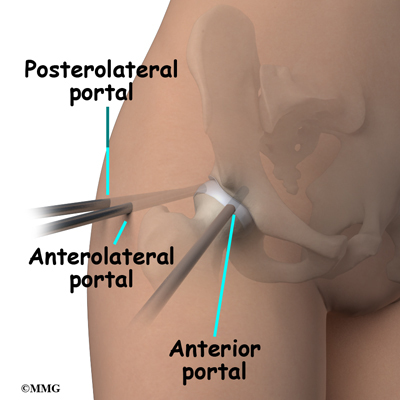

The surgeon begins the operation by making two or three small openings into the hip, called portals. These portals are where the arthroscope and surgical instruments are placed inside the hip. Care is taken to protect the nearby nerves and blood vessels. A small metal or plastic tube (or cannula) will be placed through one of the portals to inflate the hip with sterile saline.

The arthroscope is a small fiber-optic tube that is used to see and operate inside the joint. The arthroscope is a small metal tube about 1/4 inch in diameter (slightly smaller than a pencil) and about seven inches in length. The fiberoptics inside the metal tube of the arthroscope allows a bright light and TV camera to be connected to the outer end of the arthroscope. The light shines through the fiberoptic tube and into the hip joint. A TV camera is attached to the lens on the outer end of the arthroscope. The TV camera projects the image from inside the hip joint on a TV screen next to the surgeon. The surgeon actually watches the TV screen (not the hip) while moving the arthroscope to different places inside the hip joint and bursa.

Over the years since the invention of the arthroscope, many very specialized instruments have been developed to perform different types of surgery using the arthroscope to see what is going on while the instruments are being used. Today, many surgical procedures that once required large incisions for the surgeon to see and fix the problem can be done with much smaller incisions. For example, simple removal of a torn labrum or loose body can be done using two or three small 1/4 inch incisions. More extensive surgical procedures may require larger incisions. Your surgeon may decide during the procedure that the problem requires a more traditional open type operation. If this has been discussed before the operation the surgery may be performed immediately; if not, the arthroscopic procedure will be concluded and a later operation planned. Your surgeon will discuss the details of what was found at the time of the arthroscopy and what more needs to be done in the later operation.

Once the surgical procedure is complete, the arthroscopic portals and surgical incisions will be closed with sutures or surgical staples. A large bandage will be applied to the hip. You may be placed in compression stockings; compressive stockings reduce swelling and help prevent blood clots in the leg. Once the bandage has been placed, you will be taken to the recovery room.

Complications

What might go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur during hip arthroscopy. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following hip arthroscopy are

- anesthesia complications

- thrombophlebitis

- infection

- equipment failure

- slow recovery

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when blood clots form in the large veins of the leg. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible after surgery. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Following hip arthroscopy, it is possible that a postoperative infection may occur. This is very uncommon and happens in less than 1% of cases. You may experience increased pain, swelling, fever and redness, or drainage from the incisions. You should alert your surgeon if you think you are developing an infection.

Infections are of two types: superficial or deep. A superficial infection may occur in the skin around the incisions or portals. A superficial infection does not extend into the joint and can usually be treated with antibiotics alone. If the hip joint itself becomes infected, this is a serious complication and will require antibiotics and possibly another surgical procedure to drain the infection.

Equipment Failure

Many of the instruments used by the surgeon to perform hip arthroscopy are small and fragile. These instruments can be broken resulting in a piece of the instrument floating inside of the joint. The broken piece is usually easily located and removed, but this may cause the operation to last longer than planned. There is usually no damage to the hip joint due to the breakage.

Different types of surgical devices (screws, pins, and suture anchors) are used to hold tissue in place during and after arthroscopy. These devices can cause problems. If one breaks, the free-floating piece may hurt other parts inside the hip joint, particularly the articular cartilage. The end of the tissue anchor may poke too far through tissue and the point may rub and irritate nearby tissues. A second surgery may be needed to remove the device or fix problems with these devices.

Slow Recovery

Not everyone gets quickly back to routine activities after hip arthroscopy. Because the arthroscope allows surgeons to use smaller incisions than in the past, many patients mistakenly believe that less surgery was necessary. This is not always true. The arthroscpe allows surgeons to do a great deal of reconstructive surgery inside the hip without making large incisions. How fast you recover from hip arthroscopy depends on what type of surgery was done inside your hip. Simple problems that require simple procedures using the arthroscope generally get better faster. Patients with extensive damage to the hip articular cartilage tend to require more complex and extensive surgical procedures. These more extensive reconstructions take longer to heal and have a slower recovery. You should discuss this with your surgeon and make sure that you have realistic expectations of what to expect following arthroscopic hip surgery.

After Surgery

What happens after hip arthroscopy?

Hip arthroscopy is usually done on an outpatient basis meaning that patients go home the same day as the surgery. More complex reconstructions that require larger incisions and surgery that alters bone may require a short stay in the hospital to control pain more aggressively and monitor the situation carefully. You may also begin physical therapy while in the hospital.

The portals are covered with surgical strips, the larger incisions may have been repaired with either surgical staples or sutures. Crutches are commonly used after hip arthroscopy. They may only be needed for one to two days after a simple procedures.

Follow your surgeon’s instructions about how much weight to place on your foot while standing or walking. Avoid doing too much, too quickly. You may be instructed to use a cold pack on the hip and to keep your leg elevated and supported.

Rehabilitation

What will my recovery be like?

Your rehabilitation will depend on the type of surgery required. You may not need formal physical therapy after simple procedures such as a labral debridement. Some patients may simply do exercises as part of a home program after some simple instructions.

Many surgeons have patients take part in formal physical therapy after any type of hip arthroscopy procedure. Generally speaking, the more complex the surgery the more involved and prolonged your rehabilitation program will be. The first few physical therapy treatments are designed to help control the pain and swelling from the surgery. Physical therapists will also work with patients to make sure they are putting only a safe amount of weight on the affected leg.

Today, the arthroscope is used to perform quite complicated major reconstructive surgery using very small incisions. Remember, just because you have small incisions on the outside, there may be a great deal of healing tissue on the inside of the hip joint. If you have had major reconstructive surgery, you should expect full recovery to take several months. The physical therapist’s goal is to help you keep your pain under control and improve the range of motion and strength of your hip. When you are well under way, regular visits to your therapist’s office will end. The therapist will continue to be a resource, but you will be in charge of doing your exercises as part of an ongoing home program.

Femoroacetabular Impingement

A Patient’s Guide to Femoroacetabular Impingement of the Hip

Introduction

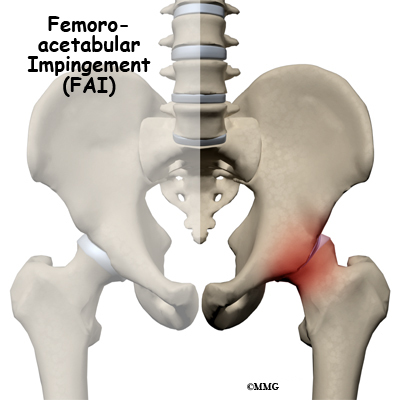

Femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) occurs in the hip joint. Impingement refers to some portion of the soft tissue around the hip socket getting pinched or compressed. Femoroacetabular tells us the impingement is occurring where the femur (thigh bone) meets the acetabulum (hip socket). There are several different types of impingement. They differ slightly depending on what gets pinched and where the impingement occurs.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the hip are involved

- how the problem develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What part of the body is affected?

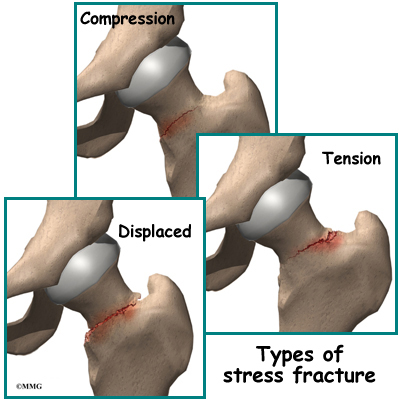

Femoroacetabular refers to the place in the hip where the round head of the femur (thigh bone) comes in contact with the acetabulum or hip socket. Two types of impingement are known to cause pinching of the soft tissues in this area.

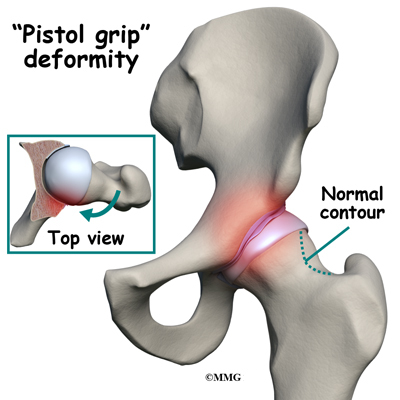

The first is called cam-type impingement. This occurs when the round head of the femur isn’t as round as it should be. It’s more of a pistol grip shape. It’s even referred to as a pistol grip deformity. The femoral head isn’t round enough on one side (and it’s too round on the other side) to move properly inside the socket.

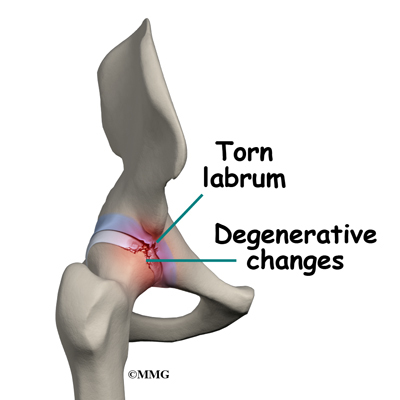

The result is a shearing force on the labrum and the articular cartilage, which is located next to the labrum. The labrum is a dense ring of fibrocartilage firmly attached around the acetabulum (socket). It provides depth and stability to the hip socket. The articular cartilage is the protective covering over the hip joint surface.

Sometimes cam-type impingement occurs as a result of some other hip problem (e.g., Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, slipped capital femoral epiphysis or SCFE). But most of the time, it occurs by itself and is the main problem. Men are affected by cam-type impingement more often than women.

The second type of impingement is called pincer-type (more common in women). In this type, the socket covers too much of the femoral head. As the hip moves, the labrum comes in contact with the femoral neck just below the femoral head.

Pincer-type impingement is usually caused by some other problem. It could be as a result of 1) hip dysplasia, 2) a complication after osteotomy surgery to correct hip dysplasia, or 3) an abnormal position of the acetabulum called retroversion. Hip dysplasia is a deformity of the hip (either of the femoral head or the acetabulum, or both) that can lead to hip dislocation.

Related Document: Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Children

Related Document: Perthes Disease

Related Document: Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Causes

What causes this problem?

The cause of the problem has been under considerable debate for a long time. Now with better imaging studies, we know that some subtle changes in the shape of the femoral head may be the cause of FAI. Other anatomical changes in the angle of the hip may also contribute to this problem.

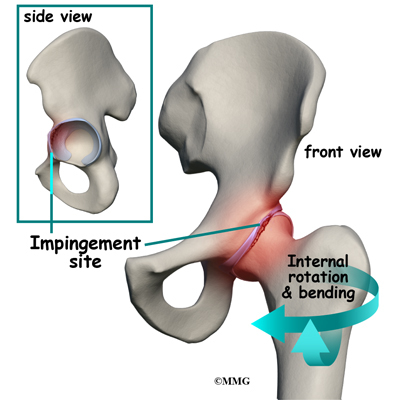

The basic problem is that the head of the femur butts up against the cartilage rim around the acetabulum and pinches it. An alternate type of femoral acetabular impingement causes abnormal jamming of the head-neck junction.

Normally, the femoral head moves smoothly inside the hip socket. The socket is just the right size to hold the head in place. If the acetabulum is too shallow or too small, the hip can dislocate. In the case of FAI, the socket may be too deep.

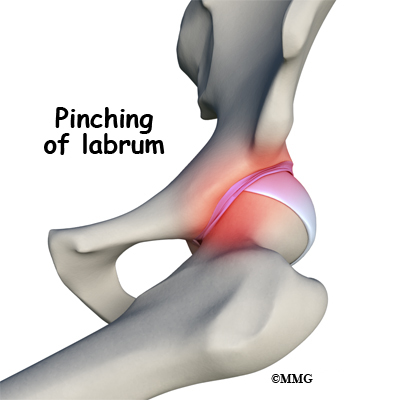

The rim of the cartilage hangs too far over the head. When the femur flexes (bends) and internally rotates, the cartilage gets pinched. Over time, this pinching or impingement of the labrum can cause fraying and tearing of the edges and/or osteoarthritic changes at the impingement site.

At the same time, with changes in the shape and structure of the hip, there are changes in normal hip movement. There may be too much hip adduction and internal rotation. Hip adduction refers to movement of the leg toward the body. Muscle weakness of the hip abductor muscles, hip extensors, and hip external rotators add to the problem. Hip abduction is moving the leg away from the body.

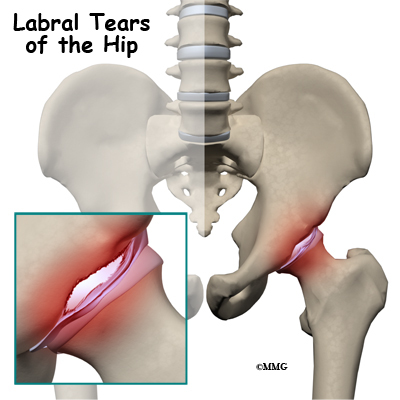

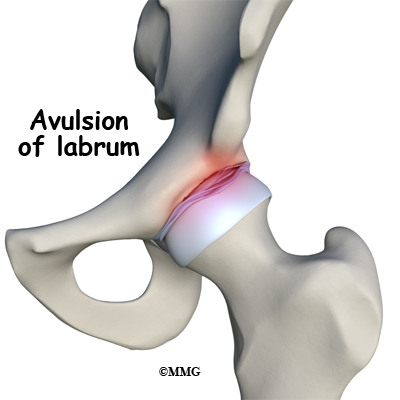

With the combined effects of anatomic changes in the hip and the resultant muscle imbalances, repetitive motions can create mini-traumas to the hip joint. The result can be an additional problem: partial or complete labral tears. A complete rupture is referred to as an avulsion where the labrum is separated from the acetabular cartilage where it normally attaches.

Symptoms

What does this condition feel like?

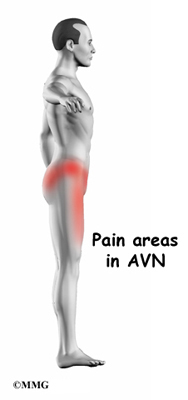

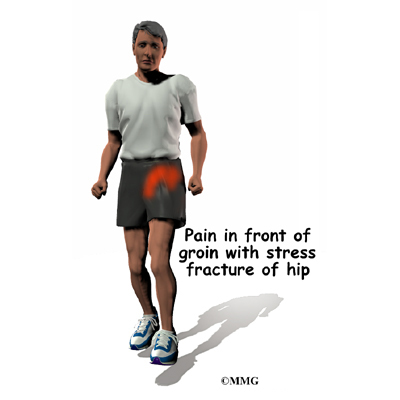

The first noticeable symptom of femoroacetabular impingement is often deep groin pain with activities that stress hip motion. Prolonged walking is especially difficult. Although the condition is often present on both sides, the symptoms are usually only felt on one side. In some cases, the groin pain doesn’t start until the person has been sitting and starts to stand up. There is often a slight limp because of pain and limited motion.

Groin pain associated with femoroacetabular impingement can be accompanied by clicking, locking, or catching when chronic impingement has resulted in a labral tear.

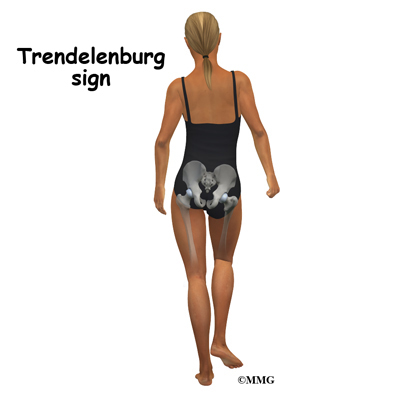

When femoroacetabular impingement and a labral tear are both present, symptoms get worse with long periods of standing, sitting, or walking. Pivoting on the involved leg is also reproduces the pain. Some patients have a positive Trendelenburg sign (hip drops down on the right side when standing on the left leg and vice versa).

As is often the case, one problem can lead to others. With femoroacetabular impingement, hip bursitis can develop. The gluteal (buttock) muscles may be extra tender or sore from trying to compensate and correct the problem. The pain can be constant and severe enough to limit all recreational activities and sports participation.

Related Document: Labral Tears of the Hip

Diagnosis

How do doctors diagnose the problem?

The diagnosis begins with a patient interview and history. Then the orthopedic surgeon performs a physical exam. The physician looks at pelvic and hip motion and palpates muscles and tendons for areas of tenderness.

Several tests can be done to identify what’s going on. The patient lies on the table on his or her back. The examiner bends the leg up, internally rotates the hip, and presses the knee toward the other leg. This position puts the hip in such a position that impingement occurs and reproduces the painful symptoms.

The clinical exam is followed up by imaging studies including X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans. X-rays show the presence of any extra bone build up as well as the position and alignment of the bones and joint. X-rays show the shape of the femoral head.

Any asymmetries (i.e., where the head is no longer an even round shape) are visible on X-rays. The radiologist and orthopedic surgeon reviewing the radiographs also look for three signs as an indication that there is retroversion: the crossover sign, the posterior wall sign, and the ischial sign.

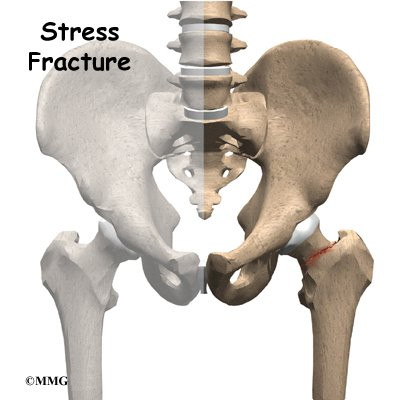

MRIs can show any damage to the labrum but not necessarily any changes to the surface of the hip joint. The presence of edema (swelling) under the bone may show up and requires further evaluation to decide if it is from femoroacetabular impingement or some other cause (e.g., cyst, tumor, stress fracture). Using MRI with a dye injected into the joint (called magnetic resonance arthrography or MRA) provides greater detail of the joint surface and may be needed.

CT scans help show the exact shape of the bone and reveal any abnormalities in the bone structure. CT scans might be the most helpful when arthroscopic surgery is planned. It gives the surgeon a better idea of what needs to be done to reshape the bone. If the procedure is going to be done with an open incision, then the CT scan isn’t necessary. The surgeon will see everything once the area is opened up.

Treatment

What can be done for this condition?

Once all the test results are available, a course of action is determined. This may be conservative (nonoperative) care with antiinflammatories and physical therapy. In some cases, surgery is recommended right away. Early diagnosis and surgical correction may be able to restore normal hip motion. Delaying surgery is possible for other patients but the long-term effect(s) of putting surgery off have not been determined.

Nonsurgical Treatment

A physical therapist will carry out an examination of joint motion; hip, trunk, and knee muscle strength; posture; alignment; and gait/movement analysis (looking at walking/movement patterns). A plan of care is designed for each patient based on his or her individual factors and characteristics.

Nonoperative care starts with activity modification (e.g., avoiding pivoting on the involved leg when there is a labral tear, avoiding prolonged periods of inactivity or activity). This part of the program must be followed for at least six months (often longer).

Improving biomechanical function of the hip involves strengthening appropriate muscles, restoring normal neuromuscular control, and addressing any postural issues. Tight muscles around the hip can contribute to pinching between the femoral head and acetabulum in certain positions. A program of flexibility and stretching exercises won’t change the bony abnormalities present but can help lengthen the muscles and reduce contact and subsequent impingement.

Some patients may also benefit from intra-articular injection with a numbing agent combined with an antiinflammatory (steroid) medication. Anyone needing surgery will also benefit from physical therapy first to address muscle imbalances resulting in abnormal movement patterns that lead to femoral acetabular impingement.

Surgery

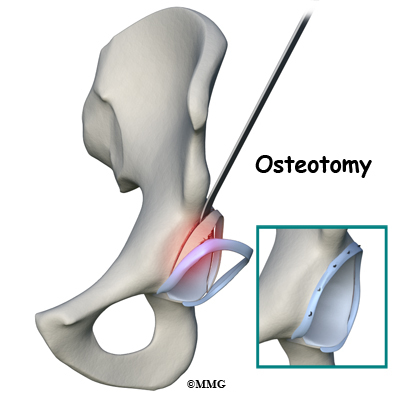

Surgery is advised when there is persistent pain despite a good effort at conservative care and when there are obvious structural abnormalities of the hip. Once it has been decided that surgery is the way to go, the surgeon has three choices: 1) full open incision and correction of the problem, 2) arthroscopic surgery, and 3) osteotomy.

With the fully open surgical procedure, the head of the femur is dislocated from the socket to make the changes and corrections and reshape it. With arthroscopic surgery, dislocation is not required. Osteotomy (reshaping the socket) is done for pincer-type impingement.

Whenever possible, the surgeon tries to save the hip. But when there is extensive damage to the cartilage, hip resurfacing or total joint replacement may be needed. There are many factors to consider when making this decision. The patient’s age, findings on imaging studies, type and severity of deformity, and the presence of arthritic changes are important.

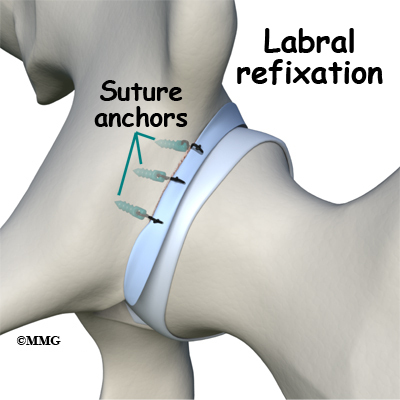

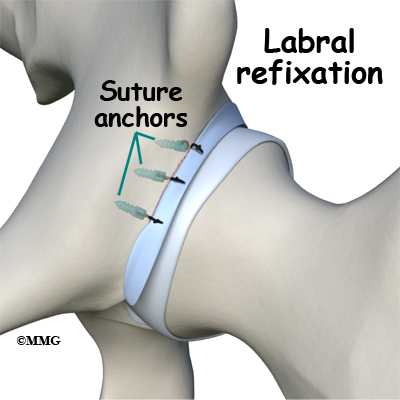

If there is a labral tear, surgery is usually done arthroscopically to repair (whenever possible) the damage. The surgeon trims the acetabular rim and then reattaches the torn labrum. This procedure is called labral refixation.

Each layer of tissue is sewn back together and reattached as closely as possible to its original position (called the footprint) along the acetabular rim. When repair is not possible, then debridement (shaving or removing) the torn tissue or pieces of tissue may be necessary.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

The goal of conservative management is to relieve pain and improve function by correcting muscle strength imbalances. When both legs have nearly equal strength, it is possible to resume a full and normal level of all activities (so long as there is no pain during any of those movements or activities).

For the young or active adult, this includes activities of daily living as well as recreational and sports participation. Older adults experiencing labral tears associated with the impingement problem may expect to be able to resume normal daily functions but may still find it necessary to limit prolonged sitting or standing positions.

After Surgery

Correction of the problem can result in improved function and pain relief. The hope is that early treatment can prevent arthritic changes but long-term studies have not been done to proven this idea.

After surgery, patients will be restricted to a partial weight-bearing status. The exact recommendations will depend on the amount of bone removed and whether or not the labrum was torn and repaired. Activity restriction is important for the first few weeks after surgery in order to avoid fatiguing or overloading the hip muscles.

Stationary bike exercises are allowed early on so long as the bike seat is kept high enough to avoid pinching at the hip during the flexion portion of the pedal cycle. Athletes and sports participants will be guided back to full participation by the physical therapist, usually five to six months after rehab. Many patients report continued improvements in their symptoms even up to the end of the first year after surgery.

Labral Tears of the Hip

A Patient’s Guide to Labral Tears of the Hip

Introduction

Acetabular labrum tears (labral tears) can cause pain, stiffness, and other disabling symptoms of the hip joint. The pain can occur if the labrum is torn, frayed, or damaged. Active adults between the ages of 20 and 40 are affected most often, requiring some type of treatment in order to stay active and functional. New information from ongoing studies is changing the way this condition is treated from a surgical approach to a more conservative (nonoperative) path.

This guide will help you understand

- what parts of the hip are involved

- how the condition develops

- how doctors diagnose the condition

- what treatment options are available

Anatomy

What parts of the hip are involved?

The acetabular labrum is a fibrous rim of cartilage around the hip socket that is important in normal function of the hip. It helps keep the head of the femur (thigh bone) inside the acetabulum (hip socket). It provides stability to the joint.

Our understanding of the acetabular labrum has expanded just in the last 10 years. The availability of high-power photography and improved lab techniques have made it possible to take a closer look at the structure of this area of the hip.

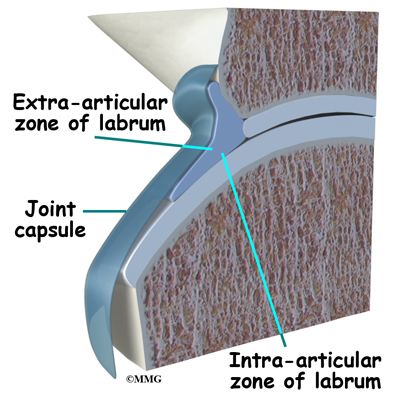

The labrum is a piece of connective tissue around the rim of the hip socket (acetabulum). It has two sides: one side is in contact with the head of the femur, the other side touches and interconnects with the joint capsule. The capsule is made up of strong ligaments that surround the hip and help hold it in place while still allowing it to move in many directions,

Finding out that there are two separate zones of the labrum was an important discovery. The extra-articular side (next to the joint capsule) has a good blood supply but the intra-articular zone (next to the joint) is mostly avascular (without blood). That means any damage to the extra-articular side is more likely to heal while the intra-articular side (with a very poor blood supply) does not heal well after injury or surgical repair.

The labrum helps seal the hip joint, thus maintaining fluid pressure inside the joint and providing the overall joint cartilage with nutrition. Without an intact seal, the risk of early degenerative arthritis increases. A damaged labrum can also result in a shift of the hip center of rotation. A change of this type increases the impact and load on the joint. Without the protection of the seal or with a hip that’s off-center, repetitive motion can create multiple small injuries to the labrum and to the hip joint. Over time, these small injuries can add to wear and tear in the hip joint.

Causes

How does this condition develop?

It was once believed that a single injury was the main reason labral tears occurred (running, twisting, slipping). But with improved radiographic imaging and anatomy studies, it’s clear now that abnormal shape and structure of the acetabulum, labrum, and/or femoral head can also lead to the problem.

Injury is still a major cause for labral tears. Anatomical changes that contribute to labral tears combined with repetitive small injuries lead to a gradual onset of the problem. Athletic activities that require repetitive pivoting motions or repeated hip flexion cause these type of small injuries.

What are these “anatomical changes”? The most common one called femoral acetabular impingement (FAI) is a major cause of hip labral tears. With FAI, there is decreased joint clearance between the junction of the femoral head and neck with the acetabular rim.

Related Document: Femoroacetabular Impingement of the Hip

When the leg bends, internally rotates, and moves toward the body, the bone of the femoral neck butts up against the acetabular rim pinching the labrum between the femoral neck and the acetabular rim. Over time, this pinching, or impingement, of the labrum causes fraying and tearing of the edges. A complete rupture is referred to as an avulsion where the labrum is separated from the edge of the acetabulum where it normally attaches.

Changes in normal hip movement combined with muscle weakness around the hip can lead to acetabular labrum tears. Other causes include capsular laxity (loose ligaments), hip dysplasia (shallow hip socket), traction injuries, and degenerative (arthritic) changes associated with aging. Anyone who has had a childhood hip disease (such as Legg-Calvé-Perthes disease, hip dysplasia, slipped capital femoral epiphysis) is also at increased risk for labral tears.

Related Document: Perthes Disease

Related Document: Developmental Dysplasia of the Hip in Children

Related Document: Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Symptoms

What does this condition feel like?

Pain in the front of the hip (most often in the groin area) accompanied by clicking, locking, or catching of the hip are the main symptoms reported with hip acetabular labral tears. Joint stiffness and a feeling of instability where the hip and leg seem to give away are also common. The pain may radiate (travel) to the buttocks, along the side of the hip, or even down to the knee.

Symptoms get worse with long periods of standing, sitting, or walking. Pivoting on the involved leg is avoided for the same reason (causes pain). Some patients walk with a limp or have a positive Trendelenburg sign (hip drops down on the right side when standing on the left leg and vice versa).

The pain can be constant and severe enough to limit all recreational activities and sports participation.

Diagnosis

How will my doctor diagnose this condition?

The history and physical examination are the first tools the physician uses to diagnose hip labral tears. There may or may not be a history of known trauma linked with the hip pain. When there are anatomic and structural causes or muscle imbalances contributing to the development of labral tears, symptoms may develop gradually over time.

Your doctor will perform several tests. One common test is the impingement sign. This test is done by bending the hip to 90 degrees (flexion), turning the hip inward internal rotation) and bringing the thigh towards the other hip (adduction).

Making the diagnosis isn’t always easy. In fact, this problem is frequently misdiagnosed at first. That’s because there are many possible causes of hip pain. The pain associated with labral tears can be hard to pinpoint. Your doctor must rely on additional tests to locate the exact cause of the pain. For example, injecting a local anesthetic agent (lidocaine) into the joint itself can help determine if the pain is coming from inside (versus outside) the joint.

X-rays provide a visual picture of any changes out of the ordinary of the entire structure and location of the hip position. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) gives a clearer picture of the soft tissues (e.g., labrum, cartilage, tendons, muscles).

One other test called a magnetic resonance arthrography (MRA) is now considered the gold standard for diagnosis. Studies show that MRA is highly sensitive and specific for labral tears. This test may replace arthroscopic examination as the main diagnostic tool. Arthroscopic examination is still 100 per cent accurate but requires a surgical procedure.

With MRAs, contrast dye (gadolinium) is injected into the hip joint. Any irregularity in the joint surface will show up when the dye seeps into areas where damage has occurred. MRAs give the surgeon an excellent view of the location and extent of the tear as well as any bony abnormalities that will have to be addressed during surgery.

Treatment

What treatment options are available?

In the past, when arthroscopic surgery was the only way to confirm the presence of a labral tear, the surgeon would just go ahead and remove the torn edges or pieces during the arthroscopic examination procedure. However, studies over the years have called this approach into question. With removal of the labrum, changes in the way the hip functioned, increased friction of the joint, and increased load on the joint led to degenerative changes and osteoarthritis.

Surgeons stopped cutting out the torn labrum and started repairing it instead. Physical therapists started doing studies that showed strengthening muscles and resolving issues of muscle imbalances could reduce the need for surgery with the traditional risks (e.g., bleeding, infection, poor wound healing, negative reactions to anesthesia).

More efforts are being made now to manage labral tears with conservative (nonoperative) care. This is a possibility most often when there are no symptoms of labral pathology. Patients with confirmed labral tears but who have normal hip anatomy or only mild changes in the shape and structure of the hip may also benefit from conservative care.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Physical therapy will probably be suggested. Your physical therapist will carry out an examination of joint motion; hip, trunk, and knee muscle strength; posture; alignment; and gait/movement analysis (looking at walking/movement patterns). A plan of care is designed for each patient based on his or her individual factors and characteristics.

Nonoperative care starts with activity modification. You should avoid pivoting on the involved leg and avoid prolonged periods of weight-bearing activities. You physical therapist will work with you to on strengthen your hip muscles, restore normal neuromuscular control, and improve your posture. All of these things can improve your hip function and reduce your pain.

Tight muscles around the hip can contribute to pinching between the femoral head and acetabulum in certain positions. A program of flexibility and stretching exercises won’t change the bony abnormalities present but can help lengthen the muscles and reduce contact and subsequent impingement.

A special strap called the SERF strap (SERF means Stability through External Rotation of the Femur) made of thin elastic may be applied around the thigh, knee, and lower leg to pull the hip into external rotation. The idea is to use the strap to improve hip control and leg movement during dynamic activities. It is important to strengthen the muscles at the same time to perform the same task and avoid depending on external support on a long-term basis.

Some patients may also benefit from intra-articular injection with cortisone. Cortisone is a very potent antiinflammatory medication. Injection into the hip joint may reduce the symptoms of pain for several weeks to months.

Surgery

Arthroscopy is commonly used to repair the torn labrum. The arthroscope is a small fiber-optic tube that is used to see and operate inside the joint. A TV camera is attached to the lens on the outer end of the arthroscope. The TV camera projects the image from inside the hip joint on a TV screen next to the surgeon. The surgeon actually watches the TV screen (not the hip) while moving the arthroscope to different places inside the hip joint and bursa.

During this procedure, your surgeon will trim the torn and frayed tissue around the acetabular rim and reattach the torn labrum to the bone of the acetabular rim. This procedure is called labral refixation. Each layer of tissue is sewn back together and reattached as closely as possible to its original position along the acetabular rim.

When repair is not possible, then debridement of the torn labral tissue may be necessary. Debridement simply means that the torn or weakened portions of the labrum are simply removed. This prevents the torn fragments from getting caught in the hip joint and causing pain and further damage to the hip joint.

In some cases, open treatment of femoroacetabular impingement and/or correction of bone abnormalities are required. These procedures are much more involved and usually will require a stay of several days in the hospital.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Femoroacetabular Impingement

Rehabilitation

What should I expect after treatment?

Nonsurgical Rehabilitation

The goal of conservative management is to relieve pain and improve function by correcting muscle strength imbalances. When both legs have nearly equal strength, it is possible to resume a full and normal level of all activities as long as there is no pain during any of those movements or activities.

For the young or active adult, this includes activities of daily living as well as recreational and sports participation. Older adults experiencing labral tears from degenerative arthritis may expect to be able to resume normal daily functions, but may still find it necessary to limit prolonged sitting or standing positions.

After Surgery

Correction of the problem causing labral tears can result in improved function and pain relief. The hope is that early treatment can prevent arthritic changes but long-term studies have not been done to proven this idea.

Recovery after surgery needed to address hip labral tears usually takes four to six months. In other words, patients can expect to resume normal activities six months after surgery. Many athletes or highly active adults find this time frame much too long for their goals and preferences.

Patients who follow the recommended rehab plan of care respond well to progression of the exercises and seem to recover faster. Discharge from rehab takes place when the patient can perform all exercises with good form and without pain or other symptoms. Any repeat episodes of groin and/or hip pain must be reported to the orthopedic surgeon for evaluation right away.

Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty

A Patient’s Guide to Hip Resurfacing Arthroplasty

Introduction

A hip that is painful as a result of osteoarthritis (OA) can severely affect your ability to lead a full, active life. Over the last 25 years, major advancements in hip replacement have greatly improved the outcome of the surgery.

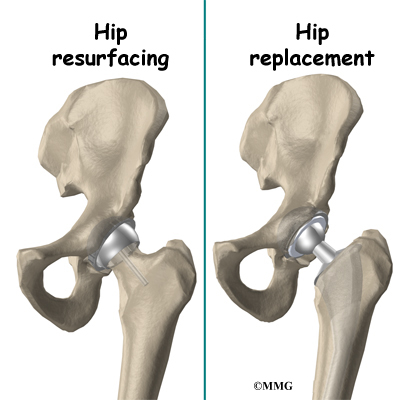

Hip resurfacing arthroplasty is a type of hip replacement that replaces the arthritic surface of the joint but removes far less bone than the traditional total hip replacement. Because the hip resurfacing removes less bone, it may be preferable for younger patients that are expected to need a second, or revision, hip replacement surgery as they grow older and wear out the original artificial hip replacement.

This guide will help you understand

- what your surgeon hopes to achieve

- what happens during the procedure

- what to expect after your operation

Anatomy

What parts of the hip are involved?

The hip joint is one of the true ball-and-socket joints of the body. The hip socket is called the acetabulum and forms a deep cup that surrounds the ball of the upper thighbone, known as the femoral head. Hip resurfacing may only affect the head of the femur or it may involve both the femoral head and the hip socket.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Hip Anatomy

Rationale

What does the surgeon hope to achieve?

The main reason for replacing any arthritic joint with an artificial implant is to stop the bones from rubbing against each other. This rubbing causes pain. Replacing the painful and arthritic joint with a new surface, allows the joint to move smoothly without pain. The goal is to help people return to many of their activities with less pain and greater freedom of movement.

The most important reason to do a hip resurfacing rather than a traditional artificial hip replacement, is to remove as little bone around the hip as possible. This is especially important when you may need a second, or revision, hip replacement as you grow older.

The most common cause for revision of an artificial hip is loosening of the pieces of the artificial hip joint where it attaches to the bone. The loosening process results in wearing away of the bone around the metal components, or parts of the artificial joint. This is especially true around the stem of the femoral component that fits inside of the femoral shaft in the traditional artificial joint. The femoral component used during hip resurfacing is placed on the outside of the femoral head and the femoral shaft is never disturbed. This means that when a revision is needed, the femoral shaft can be used to hold the femoral component as if there has never been an artificial joint and the bone in this area is virginal.

Hip resurfacing is a good option for adults younger than 60 years who have arthritis and can be expected to require a revision of their hip replacement. This procedure is not advised for anyone with bone cysts, inflammatory arthritis, or for patients with severe arthritis or osteoporosis. Generally, a traditional total hip replacement is preferred in those cases.

Preparation

How should I prepare for surgery?

The decision to proceed with surgery should be made jointly by you and your surgeon only after you feel that you understand as much about the procedure as possible. Many patients wonder when they should consider surgery. Most surgeons agree that surgery is advised when a patient’s pain and discomfort limit daily life and activities.

Once the decision to proceed with surgery is made, several things may need to be done. Your orthopedic surgeon may suggest a complete physical examination by your medical or family doctor. This is to ensure that you are in the best possible condition to undergo the operation. You may also need to spend time with the physical therapist who will be managing your rehabilitation after the surgery.

One purpose of the preoperative physical therapy visit is to record a baseline of information. This includes measurements of your current pain levels, functional abilities, and the movement and strength of each hip.

A second purpose of the preoperative therapy visit is to prepare you for your upcoming surgery. You will begin to practice some of the exercises you will use just after surgery.

You will also be trained in the use of crutches or a walker. Your therapist will also assess any needs you will have at home or work once you’re released from the hospital.

You may be asked to donate some of your own blood before the operation. This blood can be donated three to five weeks before the operation, and your body will make new blood cells to replace the loss. At the time of the operation, if you need to have a blood transfusion you will receive your own blood back from the blood bank.

Surgical Procedure

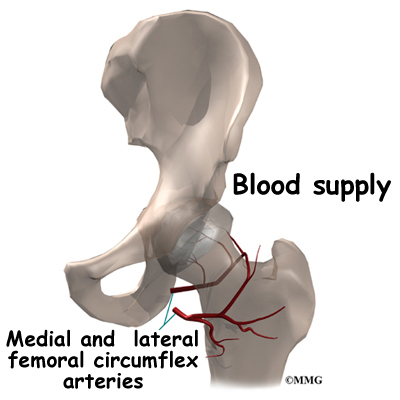

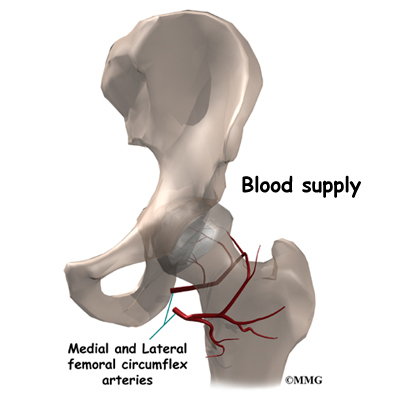

Surgeons perform this operation using several different incisions, or approaches, to the hip joint. The anterior approach from the front of the hip and the posterior approach from the back of the hip. There is no one right approach. Many surgeons prefer the posterior approach because it keeps the joint capsule intact. Keeping the joint capsule intact may reduce the risk of dislocation after the surgery and damage the blood supply less. Either approach is commonly used depending on the training and experience of the surgeon.

The operation begins by making an incision in the side of the thigh. This allows the surgeon to see both the femoral head and the acetabulum (or socket). The femoral head is then dislocated out of the socket. Special powered instruments are used to shape the bone of the femoral head so that the new metal surface will fit snugly on top of the bone.

The cap is placed over the smoothed head like a tooth capped by the dentist. The cap is held in place with a small peg that fits down into the bone. The patient must have enough healthy bone to support the cap.

The hip socket may remain unchanged but more often it is replaced with a thin metal cup. A special tool called a reamer is used to remove the cartilage from the acetabulum and shape the socket to fit the acetabular component. Once the shape is correct, the acetabular component is pressed into place in the socket. Friction holds the metal liner in place until bone grows into the holes in the surface and attaches the metal to the bone.

Complications

What could go wrong?

As with all major surgical procedures, complications can occur. This document doesn’t provide a complete list of the possible complications, but it does highlight some of the most common problems. Some of the most common complications following hip resurfacing arthroplasty surgery include

- anesthesia complications

- thrombophlebitis

- infection

- dislocation

- femoral neck fracture

- leg length inequality

- loosening

Anesthesia Complications

Most surgical procedures require that some type of anesthesia be done before surgery. A very small number of patients have problems with anesthesia. These problems can be reactions to the drugs used, problems related to other medical complications, and problems due to the anesthesia. Be sure to discuss the risks and your concerns with your anesthesiologist.

Thrombophlebitis (Blood Clots)

View animation of pulmonary embolism

Thrombophlebitis, sometimes called deep venous thrombosis (DVT), can occur after any operation, but it is more likely to occur following surgery on the hip, pelvis, or knee. DVT occurs when the blood in the large veins of the leg forms blood clots. This may cause the leg to swell and become warm to the touch and painful. If the blood clots in the veins break apart, they can travel to the lung, where they lodge in the capillaries and cut off the blood supply to a portion of the lung. This is called a pulmonary embolism. (Pulmonary means lung, and embolism refers to a fragment of something traveling through the vascular system.) Most surgeons take preventing DVT very seriously. There are many ways to reduce the risk of DVT, but probably the most effective is getting you moving as soon as possible. Two other commonly used preventative measures include

- pressure stockings to keep the blood in the legs moving

- medications that thin the blood and prevent blood clots from forming

Infection

Infection can be a very serious complication following artificial joint replacement surgery. The chance of getting an infection following hip joint resurfacing is probably around one percent. Some infections may show up very early, even before you leave the hospital. Others may not become apparent for months, or even years, after the operation. Infection can spread into the artificial joint from other infected areas. Your surgeon may want to make sure that you take antibiotics when you have dental work or surgical procedures on your bladder or colon to reduce the risk of spreading germs to the joint.

Dislocation

Just like your real hip, an artificial hip can dislocate if the ball comes out of the socket. There is a greater risk just after surgery, before the tissues have healed around the new joint, but there is always a risk. The physical therapist will instruct you very carefully how to avoid activities and positions that may have a tendency to cause a hip dislocation. A hip that dislocates more than once may have to be revised to make it more stable. This means another operation.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Hip Dislocation Precautions

Loosening

The main reason that artificial joints eventually fail continues to be the loosening of the metal or cement from the bone. Great advances have been made in extending how long an artificial joint will last, but most will eventually loosen and require a revision. Hopefully, you can expect 12 to 15 years of service from an artificial hip, but in some cases the hip will loosen earlier than that. A loose hip is a problem because it causes pain. Once the pain becomes unbearable, another operation will probably be required to revise the hip.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Revision Arthroplasty of the Hip

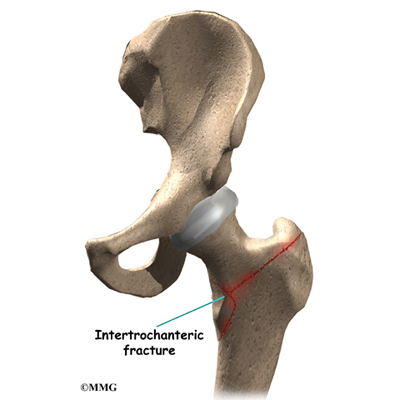

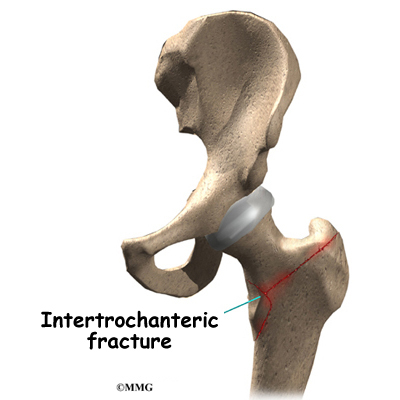

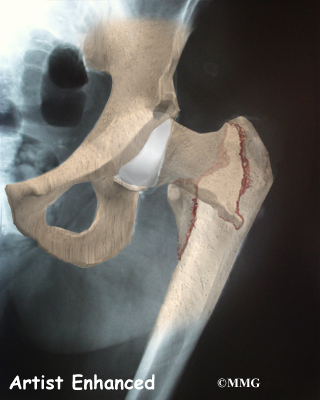

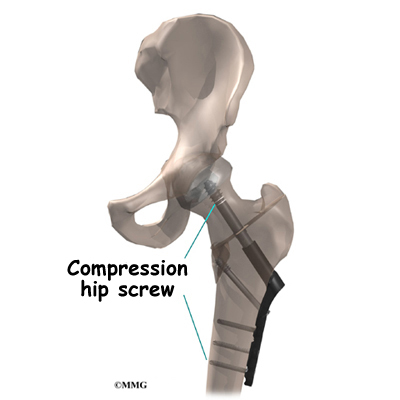

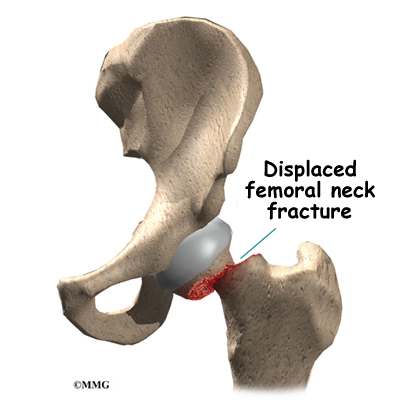

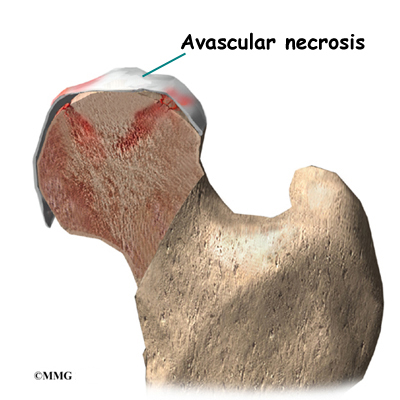

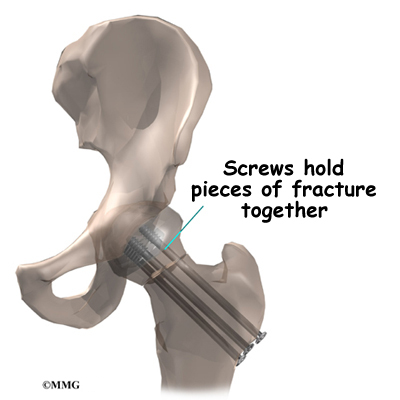

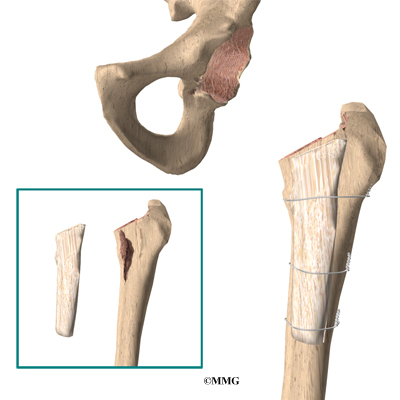

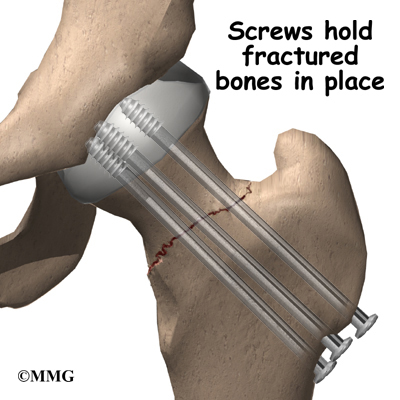

Fracture of the Femoral Neck

Fracture of the femoral neck is a unique complication of hip resurfacing. The replacement cap fits over the femoral head and ends just about where the femoral neck begins. This meeting point is an area of increased stress risk. Patient obesity, decreased bone mass, and surgical error are common risk factors in femoral neck fracture.

Leg Length Inequality

If there is any bone loss a difference in leg length can occur. When a surgeon does a traditional artificial hip replacement, the leg can be lengthened or shortened to match the other side. Because much less bone is removed during hip joint resurfacing, the surgeon cannot adjust the length of the leg. If you have a leg length difference before the procedure it will remain essentially the same.

After Surgery

What happens after surgery?

After surgery, your hip will be covered with a padded dressing. Special boots or stockings are placed on your feet to help prevent blood clots from forming. A triangle-shaped cushion may be positioned between your legs to keep your legs from crossing or rolling in.

If your surgeon used a general anesthesia, a nurse or respiratory therapist will visit your room to guide you in a series of breathing exercises. You’ll use a breathing device known as an incentive spirometer to improve breathing and avoid possible problems with pneumonia.

Physical therapy treatments are scheduled one to three times each day as long as you are in the hospital. Your first session is scheduled soon after you wake up from surgery. Your therapist will begin by helping you move from your hospital bed to a chair. By the second day, you’ll begin walking longer distances using your crutches. Most patients are safe to put comfortable weight down when standing or walking. However, if your surgeon used an uncemented prosthesis, you may be instructed to limit the weight you bear on your foot when you are up and walking.

Your therapist will review exercises to begin toning and strengthening the thigh and hip muscles. Ankle and knee movements are used to help pump swelling out of the leg and to prevent the formation of blood clots.

This procedure requires the surgeon to open up the hip joint during surgery. This puts the hip at some risk for dislocation after surgery. To prevent dislocation, patients follow strict guidelines about which hip positions to avoid (called hip precautions). Your therapist will review these precautions with you during the preoperative visit and will drill you often to make sure you practice them at all times for at least six weeks. Some surgeons give the OK to discontinue the precautions after six to 12 weeks because they feel the soft tissues have gained enough strength by this time to keep the joint from dislocating.

Related Document: A Patient’s Guide to Artificial Hip Dislocation Precautions

Patients are usually able to go home after spending two to four days in the hospital. You’ll be on your way home when you can demonstrate a safe ability to get in and out of bed, walk up to 75 feet with your crutches or walker, go up and down stairs safely, and consistently remember to use your hip precautions. Patients who still need extra care may be sent to a different hospital unit until they are safe and ready to go home.

Your staples will be removed two weeks after surgery.

Most orthopedic surgeons recommend that you have checkups on a routine basis after your joint resurfacing. How often you need to be seen varies from every six months to every five years, according to your situation and what your surgeon recommends.

Patients who have a joint implant will sometimes have episodes of pain, but if you have pain that lasts longer than a couple of weeks, you should consult your surgeon. During the examination, the orthopedic surgeon will try to determine why you are feeling pain. X-rays may be taken of your hip to compare with the ones taken earlier to see if there is any evidence of fracture or loosening.

Rehabilitation

What should I expect during my recovery?

After you are discharged from the hospital, your therapist may see you for one to six outpatient visits. This is to ensure you are safe in and about the home and workplace and getting in and out of a car. Your therapist will review your exercise program, continue working with you on your hip precautions, and make recommendations about your safety. Your therapist may use heat, ice, or electrical stimulation to reduce any swelling or pain.